< Previous

MISSION ACCOMPLISHED:

The Early Years of St Christopher’s Church

By Stephen Best

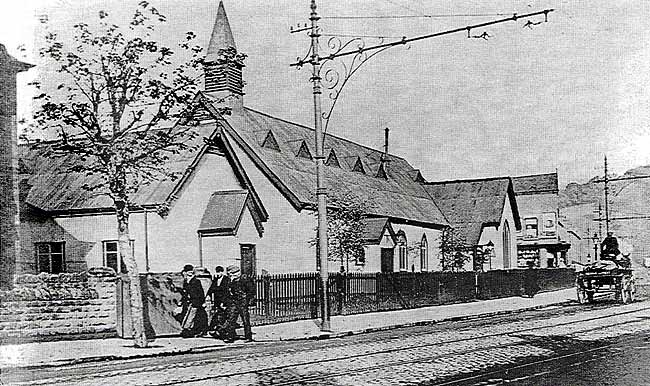

ST CHRISTOPHER’S IRON CHURCH AND SCHOOLROOM, COLWICK ROAD. A postcard dating from 1907/09.

ST CHRISTOPHER’S IRON CHURCH AND SCHOOLROOM, COLWICK ROAD. A postcard dating from 1907/09.On December 6 1952, St Christopher's church in Colwick Road, Sneinton, was rededicated after its restoration, following destruction by the Luftwaffe on the night of May 8-9 1941. Any octogenarian present at the ceremony, with local memories going back almost seventy years, might have recalled no fewer than three previous occasions when a new St Christopher's had been opened in Sneinton. In this article, the thirty years leading up to the building of the first permanent church of St Christopher are reviewed.

The earliest St Christopher's was the outcome of the missionary work of Canon Vernon Wollaston Hutton, vicar of Sneinton from 1868 to 1884. Hutton was eager to set up new churches in his populous and extensive parish, and through them to strengthen the High Church tradition in Sneinton which had been begun by the Rev. W. H. Wyatt. St Matthias', Sneinton Elements, had already been consecrated a month or two before Hutton's arrival in Sneinton in 1868, and in 1880, after much hard work, land was acquired in Bond Street, near the bottom of Sneinton Road. Here was erected in 1881 the iron chapel of St Alban; the fine brick and stone building designed by Bodley and Gamer was built several years afterwards.

Canon Hutton's thoughts turned next to those parishioners who lived in a distant part of his parish. New streets were appearing at the far end of Meadow Lane, close to London Road, and it was clear that there would soon be a potential congregation for an additional church. On August 16 1882 designs were approved of an attractive little brick church designed by Truman and Pratt of Nottingham, but these were never carried out. It seems likely that lack of money was the reason. James Edward Truman, a partner in Truman and Pratt, was a resident of Belvoir Terrace, just across the road from St Stephen's church, where he had been a communicant for over a decade. Truman had designed the church schools in Windmill Lane, Sneinton, and St Alban's iron church. He left Sneinton in 1883 for Lincoln, where he was later ordained, becoming in time vicar of St Andrew’s, Lincoln, and a canon of the cathedral. At the time of his departure Sneinton Church Magazine spoke of the architectural help he had freely given to St Stephen's and St Alban's, and remarked that it would take up less space to tell what work Truman had not taken part in, so much had he done in various ways for the church.

Canon Hutton became ill in 1882, and his poor health obliged him to be away from Sneinton from May 1883 to June 1884. After his return his health continued to decline, and he resigned in October that year. He was to die at Bournemouth in 1887, aged only 45. His successor as vicar of Sneinton was the Rev. T.W. Windley, who had served as a missionary to the Karen people of Burma; he also translated the Book of Common Prayer into the Karen language. His father was William Windley, a prominent silk-throwster and founder of All Saints', Raleigh Street. In January 1885 the Church Magazine announced that the district of St Christopher's, Meadow Lane, had been placed in the care of the Rev. George Perry, senior curate of Sneinton. Four ladies were acting as district visitors in the area, calling on families in Meadow Lane, Ashling Street, Holland Terrace, Carlton Terrace, Sutton Street and Meadow Terrace. A Sunday School for boys had been opened in Ashling Street, and it was hoped to start one for girls. Most important, the parish intended to put up a temporary church as soon as land could be found. By February a room had been lent for the girls' Sunday School, and a men's class begun at 54 Meadow Lane. Events now moved quickly. As the vicar wrote in his annual address to the parish, it was felt that it was time that the church did something 'for the welfare of the people living at the bottom end of Meadow Lane', and so achieve what Canon Hutton’s illness had prevented him from seeing through. A bank loan was arranged, sufficient for the immediate building of an iron church. £400 was needed, the low lying nature of the ground in the area making it necessary to put in expensive foundations. In July it was reported that plans and estimates had been prepared 'by Mr C. Kent, of London for erecting an iron room to be used for Divine Worship, and for school purposes and for meetings. A piece of land is to be rented from Earl Manvers, and the Committee hope eventually to be able to acquire possession of it, but land in that part is very costly'. On July 25 (St James' and St Christopher's Day), 'a large and dignified possession left the parish church for the new mission district chanting the solemn litany'. Hymns were sung on the way, and in Meadow Lane the procession was joined by about 60 scholars and teachers of St Christopher's Sunday School. The Rev. George Perry explained the object of the service : to 'take possession' of the site, while the Rev. A. Meugens of Carlton explained that the name of the Patron Saint would help to keep fresh 'the memory of the late great Bishop of Lincoln'.

35 years after this, in 1920, Mr Perry (who since 1890 had assumed the surname Perry-Gore) wrote to the then vicar of St Christopher's, the Rev. J. H. Taylor, giving him an account of the early days of the mission church. His letter, which by great good fortune survives in the church safe, contains much valuable detail. Perry-Gore related that at the London Road end of Meadow Lane, a colony of houses had grown up, 'chiefly occupied by railway servants, leather and canal workers'. Two main factors, he wrote, had influenced the choice of St Christopher as the patronal saint. First, Bishop Christopher Wordsworth of Lincoln (in which diocese Sneinton was included until 1884) had taken a great interest in Sneinton church, and had recently preferred two of Sneinton's assistant curates to incumbencies in Lincoln. It was therefore natural that Sneinton churchpeople wished to give his name to the new mission church, though Bishop Wordsworth's death in May 1885 meant that he never saw St Christopher's built. Secondly, he stated, the fields between St Stephen's church and the new mission were often under water when the nearby River Trent was in flood; this recalled the St Christopher legend, in which the saint carried the Christ Child across water.

On July 31 1885, six days after the procession, plans were submitted for a new St Christopher's by R. M. Webster, who was associated with the men's class. These plans, for an iron church, were not approved, on the grounds that the doors opened inward, and that there was no closet. There is no trace of the plans being altered and resubmitted (they are now missing), but all must have been put right very quickly, as St Christopher's was, within a very short time, open for public worship. The Diocese of Southwell day book for August 24 records the granting of a licence to hold Divine service in St Christopher's Iron Mission chapel, for the convenience of the Inhabitants residing at a distance from the parish church of Sneinton.' The church magazine for September reported on the building's progress: 'The Iron Church is now roofed in. The roof and walls are lined with felt, which will make the building warmer in winter and cooler in summer.' Accommodation for 200 was planned, though local opinion suggested that this was unlikely to be large enough. The Building Committee expected that the iron church would meet all needs for some time to come, but said that they would be pleased to be proved wrong.

The great day came on September 26 1885 and was fully reported in the Nottingham Evening Post two days later: 'On Saturday evening the Bishop of Southwell formally dedicated the mission church of St Christopher, which has been erected on a piece of ground at the end of Meadow Lane, near the Canal and London Road.... The interior is fitted up in the usual manner, and in lieu of pews, chairs are provided for the congregation. The altar is of oak, beautifully carved, and various presents have been made to the church, including two altar lights, a lectern, and a fine oak cross, which was given by the working men's class....' The large congregation heard the Bishop, Dr George Ridding, congratulate them on the new church, and an offertory at the close of the service realised £11.12.2d. At Evensong, Charles Frost, of London Road, was commissioned as the church's first lay reader. In addition to the Bishop, the vicar of Sneinton and the curate-in-charge, over a dozen clergy were present to hear the church dedicated.

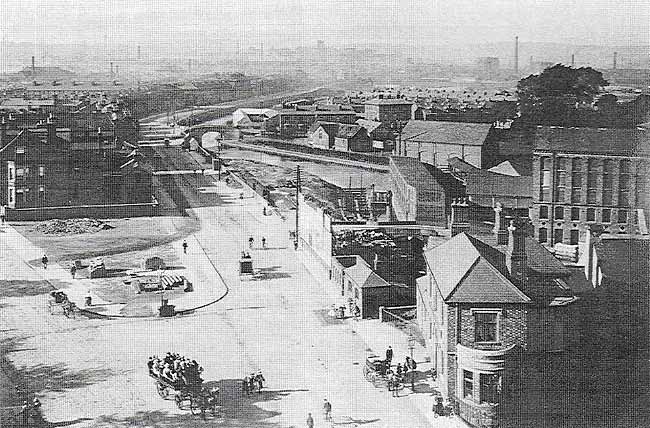

LONDON ROAD AND THE CANAL, about 1903, photographed from the roof of the Town Arms, Trent Bridge.

LONDON ROAD AND THE CANAL, about 1903, photographed from the roof of the Town Arms, Trent Bridge.The first St Christopher’s mission church stands on the canal bank. Some way to its left is Meadow Lane bridge, and to the right of the former church is a board advertising the laundry which had taken over the building. (Courtesy Nottinghamshire Local Studies Library).

For anyone still unsure of the location of the first St Christopher's, it should be said that it stood almost on the canal bank, near the old Meadow Lane bridge. The Trent Navigation pub is almost opposite, and Notts County's football ground only a few yards away. Church and football ground, though, were never going concerns at one and the same time.

References to St Christopher's cropped up in Sneinton Church Magazine throughout 1886. The vicar, in his annual address, ruefully observed that although the church nominally accommodated 200, only 150 could sit and kneel in comfort. 'The bright, cheerful services, the reverent ritual, and the plain teaching has naturally attracted many persons from the overgrown parishes adjoining....' he reported. (At the time of the opening of the mission he had said that 'the ritual of the chapel will be simple, dignifiedand "Anglican")'. Although £200 was still needed to pay off the debt on the iron church, it was soon decided that the building would have to be extended, and during the summer a leaflet was printed, publicising St Christopher's Building Fund. Extra capacity of 170 seats was desirable, and an appeal for £420 was being made, to enable the financial burden to be lifted. Some well-known Sneinton names appeared on the Building Committee, among them John Steedman of Sneinton Hollows, head-master of St Ann's Well Road Board School : Richard Adams and Joseph Platts, Lace manufacturers who lived in Sneinton Road : C.F. Hole, organist and choirmaster at Sneinton church, and a teacher at Sneinton Church School : and Samuel Richards of Castle Street, who had a printing business in Bath Street. Donations already received included £10 each from Charles Parker of Sneinton Hollows and Miss Marion Tomlin of Belvoir Hill. Miss Tomlin, one of a notable Sneinton family, was to be a steadfast contributor to St Christopher's. Of those who had promised annual subscriptions, the vicar and Mrs Davidson of Sneinton Manor each committed £5 a year. The appeal must have gone well, as on September 27 the new transepts and lengthened nave were dedicated; the ceremony took place on the last day of St Christopher's first Harvest Festival. Evensong began with the choir entering, chanting Psalms 47 and 132, and ended with the singing of a solemn Te Deum. It is evident that the liturgical traditions of St Stephen's were being maintained at the mission church, as they would be until the end of the nineteenth century. The congregation 'many of whom were formerly dissenters', heard a sermon by Canon Trebeck of Southwell, who was Bishop Christopher Wordsworth's son-in- law. In this the canon mentioned that the church's dedication was partly a memorial to the late Bishop, who was further remembered by a new altar plate given on that day by his daughters, in memory of him and of his wife. Among other glimpses of St Christopher's in 1886 afforded by the parish magazine was one snippet of information which caused this writer some surprise; in the list of altar servers for Christmas Day and for other Sundays was the name of Stephen Best.

1888 brought a distinguished presence to St Christopher's in the person of the Ven. R.J. Atlay, former Archdeacon of Calcutta, who was looking after the parish of Sneinton during the vicar's absence through illness. He took part in a Lent series of half-hour services at the mission church, the Good Friday events including 'Pictures of the Passion, by Lime Light'. That summer saw the provision of a schoolroom next door to the iron church, to make it possible for teas, concerts and social gatherings to be arranged. The magazine also commented that 'A room that men and youths could use in the evenings would supply a serious social want in the neighbourhood'. Plans for a parish room were drawn up by Hadfield & Frost, builders, of Launder Street, in the Meadows, but the building that officially opened on October 23 by the Rt Rev. Edward Trollope, Bishop Suffragan of Nottingham, was considerably larger than had originally been envisaged. To mark the event the room was decorated with curtains, flags and evergreens, and a sale of work was held; all this 'gave the room quite a brilliant appearance'. It was appropriate that Mrs Turney, the Mayoress, was among the notables present, as many of St Christopher's congregation were employed at the Trent Bridge leather works of her husband, Mr (later Sir John) Turney. Bishop Trollope was another clergyman related to Bishop Wordsworth, and was especially welcomed on that account by the Rev. George Perry.

Years later, in his letter to the Rev. J.H. Taylor, George Perry-Gore remembered some of the friends and benefactors of St Christopher's in its early years. 'Among the first to exhibit interest and help', he wrote, 'was the Lord of the Manor, the late Lord Manvers'. (We shall, however, meet Lord Manvers again before long, in sterner mood). He also recalled that the Rev. T.W. Windley had given the oak altar, designed by a clergyman friend of Perry-Gore's, and made in Sneinton Hermitage by a local joiner.

Mr Perry-Gore left the mission church in 1890, on being appointed vicar of St Matthias', Sneinton. His replacement was the Rev. C.F.G. Turner, curate of Hoveringham, who had been received into our Communion from the Roman obedience'. Turner’s first task, reported in the December Sneinton Church Magazine (as it was now titled), was to address the heavy debt which still encumbered the buildings, and explain his proposals for a united effort to clear it. Turner was to remain at St Christopher's for less than a year, and was succeeded by the Rev. W. G. Spearing, one of the assistant curates at St Stephen's. The magazine for June 1891 comforted disconsolate worshippers at St Stephen’s with the words: 'After all Mr Spearing is not going to the North Pole or the Cannibal Islands; he will only be separated from us by that attractive bit of country road called Meadow Lane...' Houses had been springing up off Meadow Lane over the previous few years, and I cannot resist mentioning a chance discovery made during the preparation of this article. Three of the streets here, Meadow Grove, Holme Street, and Freeth Street, had originally been intended to bear the names Dace Street, Chub Street, and Roach Street. The authorities, however, insisted on other names; perhaps they feared that the development would outgrow suitable names of freshwater fishes, and result in Minnow and Stickleback Streets?

Further gifts from Mrs Davison and Miss Tomlin were mentioned at about this time, and another name came in for special comment in 1891 and 1892. A superfrontal for the altar was used at Christmas, and the following Easter Day saw the use of a handsome altar dossal. Money for the first was received 'through Miss Story, to whose energy in collecting we are always indebted', while the Magazine remarked of the dossal: We owe this to the exertions of Miss Story, who works so hard to make St Christopher's beautiful.' This was almost certainly either Miss Mary Sophia or Miss Jane Blanche Story, surviving daughters of Major-General Valentine Story of Forest Lodge, Mount Hooton Road. Another of the general's daughters, Meina Story, was a benefactor of St Stephen's, where she is commemorated by a stained glass window in the Lady Chapel. November 21 1891 saw 'a very lively entertainment' in the parish room, the performers appearing 'for the first time in a bright and effective new dress'. The magazine congratulated them all on doing their best, and thanked the ladies and gentlemen who had helped with music and costumes. It is interesting, in view of the way words change their meaning with the passage of time, that these wholesome entertainers rejoiced in the name of 'the Bimbo Minstrels'. Money was still a nagging problem, and the performance of a Mr Dent, who did a conjuring act at St Christopher's Sunday School prizegiving, brought a wistful thought from a writer in the February 1892 parish magazine: 'Could not Mr Dent's method of providing himself with the needful, by catching the half- crowns flying about in the air, be utilized for paying off the debt which, like a load, hangs upon St Christopher's?'

Throughout the year the financial plight of the mission was discussed in the magazine; St Christopher's was 'saddled with a very heavy debt' and insufficient money had come in even to pay off the interest. If the work of the church was to go on, something had to be done. Another worry came to the fore in September: 'It is a matter for great regret that among our congregation there are very few who actually reside in the district attached to St Christopher's'. It was planned to make house calls, distribute handbills, and hold open-air services to increase local awareness of the mission church. Earl and Countess Manvers gave £15 towards reducing the debt, and various fund-raising efforts realised nearly £200.

1893, however, found affairs at a very low ebb. With the departure of the Rev. W. G. Spearing it was decided that the mission church would henceforth be served direct from Sneinton parish church, rather than continue to be run separately by a curate- in-charge answerable to the vicar. Hardly had this decision been taken, than the vicar received a bombshell in the form of a letter from Mr Wordsworth, Earl Manvers' agent. Lord Manvers, it is worth repeating, was not only patron of the living of Sneinton, but the principal landowner of the parish, and owner of the ground on which St Christopher's stood. As the Earl's mouthpiece, Wordsworth had unwelcome news for the congregation, who were able to read his letter in the April magazine. 'St Christopher's does not serve any portion of Lord Manvers' property - not a single member of the congregation, I believe, residing upon it, but on the other hand it is a serious strain on the living of Sneinton belonging to his Lordship, which certainly has no need for any drawback of this kind, as it requires all the help it can get to minister to those who live, in what I may term Sneinton itself. Lord Manvers is of the opinion that if those who worship at St Christopher's desire a church and regular services, they must support it sufficiently to enable it to meet its obligations and current expenses, without any call on the vicar. If this is not done he will have to consider whether he is justified in allowing the tenancy to continue.' It is abundantly clear that Earl Manvers felt that his responsibilities towards the parish of Sneinton were, first and foremost, to parishioners who lived on his land; one cannot escape the conclusion that the writing was now on the wall for the first St Christopher's. Underlining his loyalty to the church in Sneinton, Lord Manvers sent a gift of £100 to St Stephen's in June, and the vicar was at pains to stress that: 'this, after all, is only another example of the liberal spirit in which his Lordship has always acted towards Sneinton ' The summer weather had, meanwhile, brought further problems for the mission church: We advise the churchwardens to consider the possibility of a sliding roof: a few more Sundays like June 18th will leave the congregation a liquid mass on the floor'. The August magazine returned, however, to more serious matters. St Christopher's people had to face five unpalatable facts. If arrears in ground rent were not paid, Lord Manvers would not agree to renewal of the lease. The expenses account was in deficit, and a former organist had still not been paid, a state of affairs which reflected badly on the church. Money towards the Sunday School treat had fallen below last year's total. Several items needed for the church could not be purchased, as there was no money available. Last, and more serious, unless the church paid its way, Lord Manvers would take steps to close it. The congregation were warned that if they were expecting that the cash would be found for them, then the collapse of the whole concern would be a matter of a short time. To fight off closure, a sale of work was held on November 30, and raised £95. It was stressed afterwards that such a sum would have been far beyond the means of the congregation, but luckily 'they had great and noble friends.' One of these was the Duchess of St Alban's, who had opened this rather grand event. 'It is reported to us', said the magazine, 'that the line of private carriages extended almost to the cattle market. They could afford their carriages, and the bicycle for two, on this occasion, was not in request for the Duchess and Lady Laura.' The last named was Lady Laura Ridding, wife of the Bishop of Southwell, who may not have been as familiar with the popular song 'Daisy Bell' as the writer of the report obviously was. A note of great optimism was apparent after the sale of work, and it was stated that the debt on the church had 'departed like melting snow'. There was, worryingly, still the debt on the parish room, the church magazine urging the guarantors to come forward 'at once, with liberal donations' to clear it off. The overwhelming impression received, though, is of a congregation totally unable to raise the money needed for St Christopher's, and having to rely on periodic bouts of generosity from wealthy well-wishers.

No parish magazines survive which might throw light on events at the Meadow Lane church in its final years, and the Sneinton vestry minutes and the Manvers Manuscripts are silent on the eventual fate of the mission church. In June 1898, however, there were further developments, when plans were submitted by the Nottingham architects W. & R. & F. Booker, for the bodily removal of St Christopher's iron church from Meadow Lane, and its re-erection in Colwick Road. On the plans, the building was described as 'Timber framed, covered externally in corrugated iron, and lined in matchboards'. A new, densely populated suburb was about to take shape, with numerous residential streets on either side of Colwick Road. A new church would soon be needed here, and it was possible at this stage of development to earmark a central and convenient site. Earl Manvers was owner of the Colwick Road land, as he was of the Meadow Lane site. Nothing, however, came of the Booker proposal, and despite a legend to the contrary, St Christopher’s, Meadow Lane, was never taken down and put up again in Colwick Road.

THE 4th EARL MANVERS not long after his successsion to the title.

THE 4th EARL MANVERS not long after his successsion to the title.The next event of importance in the St Christopher's story was the death, on January 16 1900, of Lord Manvers, at the age of 74. His Nottingham Daily Guardian obituary called him a firm friend of the Church, as patron of fifteen livings. He was, said the Guardian, 'A man of singularly kind disposition. Under an apparent brusqueness of nature there lay the innate and old- fashioned courtesy which unhappily appears every day to be becoming more rare.' St Christopher's people might indeed have felt that their landlord's brusqueness had been well to the fore in recent years. His heir, the 4th Earl, was 45 years old, and was to see great changes at St Christopher's. The old mission church (in fact not very old - less than sixteen years) did not long survive his succession to the title. A local newspaper of February 1902 recalled that the first St Christopher's had closed 'two years ago', but this cannot be correct; a surviving register of services for the mission contains entries up to January 27 1901, when they cease abruptly. In the absence of any other likely date we must, I think, conclude that this was the last Sunday of the Meadow Lane church. No mention was made of its closure at this time in the Nottingham press, but local newspapers were much preoccupied with the news of Queen Victoria's death on January 22, and it is possible that the end of St Christopher's escaped notice. Entries in the register such as 'Stations of the cross', on April 13 1900, suggest that Sneinton's High Church ritual continued there to the last. Following closure of the church, the Meadow Lane buildings were used for the remaining twenty years or so of their existence, first by a laundry, then by a builder. The modem premises of the B. G. U. Manufacturing Co. today occupy the canal-side land where the first St Christopher’s used to stand, and nothing survives to suggest that there was ever a church here.

A positive development of 1901 was the submission of plans for a new church in Colwick Road by the architect A. R Calvert of Low Pavement. Described as 'a corrugated iron and wood church for Earl Manvers', it was quite different from the Meadow Lane church which Bookers had planned to move to Colwick Road. Work on the new iron building progressed reasonably quickly, and the local press accorded extensive coverage to its dedication by the Bishop of Southwell, Dr. Ridding, on February 7 1902. The Daily Guardian welcomed another development of Church work in 'that growing district of Nottingham.' The long-recognised need for a church here had been met 'through the generosity of Earl Manvers, who has not only given the site, but erected thereon at his own expense a spacious and substantial church.' It had seats for 350, and was lined throughout with deal,* presenting 'a bright and attractive appearance'. Adjoining the church was a parish room, capable of accommodating about 200 people. The Guardian reported the transfer to the new church of the font and organ from the old St Christopher’s. 'The whole of the work', continued the paper, 'was carried out under the supervision of Mr W. H. P. Norris, agent to Earl Manvers'. The last-named gentleman had taken over the post formerly occupied by R. W. Wordsworth, who had been mentioned in the old Earl's will as 'my faithful friend and agent', and had been left a bequest of £200.

The dedication service was intoned by the Rev. Richard Bevan Pyper, the first chaplain of the new St Christopher's. St Christopher's was still a mission church within St Stephen's parish, but would increasingly be seen as a church under the particular patronage of Earl Manvers. The vicar of Sneinton, the Rev. A. M. Dale, read the lesson, and an anthem was sung by the choir of All Saints', where Pyper had lately been curate. Over twenty of the clergy were present at the ceremony. In his sermon, the bishop sounded a note still familiar in the 1990s, by speaking of the unhappiness caused by disunity within the Church: 'the members of the Church of England felt deeply the taunt which could truly be levelled at them as to the divisions among themselves, the differences between good men in their own Church, who attacked one another as if they were enemies ....' The bishop believed that Anglican and Nonconformist laymen should meet one another, discuss their differences, and try to come together 'in a loving spirit, without sacrificing convictions.' He trusted that all connected with St Christopher's would work in the district 'in Christian charity and unity, and that all religious people around would consent to labour in harmony with them.' A collection was taken, amounting to £15. The first baptism at the new church, that of Frederick Clarence Smith, 84 Sneinton Boulevard, took place on February 9.

In 1903, the Rev. R. B. Pyper left, to be replaced as chaplain by the Rev. Henry Biddell. While at St Christopher's, Biddell published in 1904 'For Christ and the Empire: a book of verses'; this little book bore the statement that profits of the first edition would be given 'to assist the work in St Christopher's, Sneinton, Nottingham.' Two years later Biddell was succeeded at St Christopher's by a man who was to make a lasting mark on Sneinton. This was the Rev. John Henry Taylor, who arrived in 1906 in his middle thirties, and was to remain at St Christopher's until 1932. Taylor Close off Sneinton Boulevard is named after him. His vigorous ministry saw St Christopher's quickly outgrow the iron church. The needs of the district had already been recognised in the previous year with the building of a new mission room, to Bookers' designs, in, ironically enough, Meadow Lane. Standing near the comer of Moreland Street, the new building was much closer to Sneinton proper than the old mission church had been. It was extended in 1908, the plans for the extension being submitted in the name of 'Rev. J. H. Taylor, Chaplin'. This mission room continued to serve the neighbourhood until the night of May 8-9 1941, when it shared the fate of the church, being destroyed in the air raid which caused much loss of life in Meadow Lane; at the Co-op bakery down the road forty-nine employees and men of the Home Guard were killed, and others injured.

1909 was a year of major change at St Christopher's which became, for a week or two, the subject of considerable press interest. It had become obvious that a much larger, permanent church was urgently required, and in July plans were announced of the proposed new church, to designs by F. E. Littler ARIBA. The existing iron church and schoolroom were to be kept for use by the congregation, but since they occupied the site on which the new building was to be erected, they had to be got out of the way before work could begin on the permanent church. What fascinated the newspapers, and remained for years in the memory of eye-witnesses, was the method by which this was achieved. The operation started on October 9, the Nottingham Guardian of the 10th containing an arresting headline:

'SHIFTING A CHURCH INTERESTING SPECTACLE IN NOTTINGHAM.

SCHOOL BUILDING ROLLED 40 FEET'.

The paper remarked on the use of a technique which was 'unique as far as Nottinghamshire goes, although the practice is frequently resorted to in America.' It had been realised that if the iron buildings were dismantled before removal, the job would take longer and cost more. Accordingly, the plan was to move the church and schoolroom without taking them to pieces first. 'This novel 'shift' was commenced yesterday' reported the Guardian, 'and proved a source of attraction to a large number of people in the district.' New foundations had been prepared during the previous three weeks, and the school-room, as the smaller building, and technically easier to move, was tackled first. Let the newspaper describe what was involved: 'The removal was not without risk, for the whole building, which is 46 feet long, and over 20 feet wide, had to be pulled along lines over a trench nearly the whole of the way. First of all the building was loosened from the foundations, and huge beams affixed to the hydraulic jacks and placed on the rollers. The lines consisted of stout wooden beams running from one foundation to the other, and as the 40 feet over which the building had to be taken was a slight decline, the work was rendered much easier. The haulage was done by means of two large 'crabs' [portable winches] the ropes being fastened to the beams under the building. Some 16 or 17 were engaged on the work and the whole operation only took four hours. The schoolroom now stands over its new foundations, and the beams will have to be removed, and the building gradually lowered into position by means of the jacks. The whole of the furniture was left in the room, and all that remains to be done before it can be used is to lower it into position, make a road across the trench over which it has been moved, and connect the gaspipes. The church, which is a much larger building, will be moved next week'. The Nottingham Daily Express added that the work was done by a local firm, T. Barlow & Co., superintended by a local man, F. English; and carried out entirely by local workmen. Despite the fact that the schoolroom, which had been used as an institute, was moved with two billiard tables inside it, the only damage had been a slight displacement of one or two floorboards.

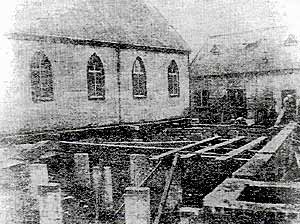

THE MOVING OF THE IRON CHURCH. COLWICK ROAD.

THE MOVING OF THE IRON CHURCH. COLWICK ROAD.Photograph from the Nottingham Guardian of October 25 1909. (Courtesy of Nottinghamshire Local Studies Library).

On October 21 work began on moving the church, the Nottingham Guardian heading its report: A WONDERFUL FEAT'. The building had to be moved some 70 or 80 feet, but the job had been held up after signs of structural weakness had been found in it as undermining began, prior to jacking up the church. The previous two days had been occupied in laying the huge wooden 'rails' from the church to its new foundations; it would be pulled along these on steel rollers, in an operation similar to the one which had shifted the schoolroom, now ready for use. 'Some idea of the enterprise which must characterise the promoters of the scheme will be gathered when it is stated that the church is roughly estimated to weigh between 60 and 80 tons, while it is 84. ft long and 40 ft. wide.' The church had, however, been moved only a few inches when work had to stop. The Guardian attributed the hold-up to a defect in a windlass, while the Express stated that a couple of ropes had snapped. The move would be a lengthy business, as each rail would need examination at every foot of distance covered; this was to ensure that the building would be properly aligned over its new foundations. The Express reporter, evidently well-read, produced a memorable simile in describing the start of the move: 'Groaning like Aesop's mountain in labour, the whole building started slowly forward, and was kept moving by almost imperceptible degrees towards its goal.' Three days later the Guardian published two dim, but fascinating photographs showing the work in progress, and on October 28 the Express reported that 'the arduous undertaking' was not yet complete. The iron church, however, now rested on its rollers above the new foundations, and it was hoped that a service could be held in it on the following Sunday.

The iron buildings now lay some way back from Colwick Road, and the land fronting on to this road was thus freed for site preparation for the permanent church. Years afterwards in April 1932, the Rev. J. H. Taylor was interviewed by the Evening Post as he was about to leave Sneinton to become vicar of Calverton. Recalling the moving of the iron church and schoolroom, he stated that the rollers used for shifting the buildings were five-inch gas pipes, and that the two buildings were moved across 'a small ravine'. The departing vicar ended his recollections with a phrase often afterwards quoted locally when the events of 1909 were mentioned. The schoolroom and church, he said, had been rolled from one site to the other 'without so much as breaking a gas mantle'.

On November 25 1909 a three-day bazaar was opened to raise money towards the costs of moving the old buildings and erecting the new one. It was thought that the total bill would amount to £7,000, a figure later revised to £8,500. Of this, £2,000 had been given anonymously, and almost another £1,000 raised. It was hoped that churchpeople living outside Sneinton would offer generous help, the Nottingham Guardian pointing out that the district had very few well-off residents, and that the congregation had made sacrifices in raising as much money as they had done. Bishop Hamilton Baynes, vicar of St Mary's, told the audience at the bazaar opening that St Christopher's was tackling, in a way, a church problem widespread in Nottingham. There were too many church buildings in the old centre of the city, but too few in the new suburbs. St Christopher's had shown them how the difficulty could be met by placing their church on wheels and setting it rolling He would like to see Mr Dodds and his church rolled into the suburbs.' The Rev. M. A. Dodds was vicar of St Philip's, Pennyfoot Street, an inner-city parish about to become significantly depopulated through slum clearance.

Countess Manvers performed the opening ceremony, her husband being busy at the House of Lords. She and the Earl, she said, greatly appreciated the splendid work done by Mr Taylor at St Christopher's, and looked forward to the laying of the foundation stone of the new church. In reply, the chaplain pointed out some of the problems of having a church which could accommodate less than 300 people in a mission district with a population of over 9,000; on Catechism Sunday they had had to squeeze in seven hundred children. He paid tribute to the kindness of Lord Manvers, who 'had built the present church and given the site, and paid the greater part of the clergyman's stipend', and had proved most generous to the new building. The final day of the bazaar was opened by Lord Henry Bentinck, past and future MP for South Nottingham, who was standing in for the unwell Councillor Albert Ball, the mayor. Ball had, however, sent his brother along to say how strongly he supported the St Christopher's building scheme. He had known Mr Taylor during his curacy at All Souls', Radford; 'Radford missed him very much, but what was Radford's loss was Sneinton's gain.' The first two days of the bazaar, it was reported, had raised £150. Well-known local patrons of fund-raising events at St Christopher's during 1909 included the incumbents of St Mary's, St Philip's, St Saviour's Arkwright Street, St Stephen's Hyson Green, and Holy Trinity. Among Sneinton residents to provide financial help were the Misses Webster, of Belvoir Terrace; they were daughters of John Webster, for many years in the nineteenth century a Sneinton churchwarden, and remembered, forty years after his death, as 'the uncrowned King of Sneinton.'

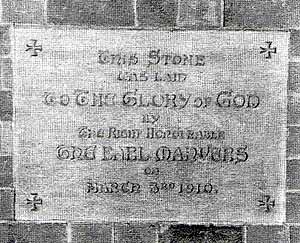

THE FOUNDATION STONE of the permanent church.

THE FOUNDATION STONE of the permanent church.The laying of the foundation stone looked forward to by the Countess took place on March 3 1910, and the Earl, of course, performed the ceremonial task with trowel and mallet. It seemed only the other day, he said, since he had attended the opening of the iron church, but the growth of the neighbourhood had made a new church necessary sooner than he had expected. Lord Manvers remarked that he might have hesitated to perform the ceremony had he not known that the new church would have a large attendance. 'He knew people who might attend, and did not, and a good many of them amongst the leisured class. He knew what the restlessness of the present age had produced, the way in which many people spent the whole of Sunday rushing about the country in motor-cars. He knew that St Christopher's was well attended, not only by women but by working men, which was as it should be .... One of the great advantages of that church was that there would always be good hearty services, with the ritual of a moderate character, which were the kind that appealed most largely to the working classes.' The Earl was disappointed that more contributions had not been forthcoming for the new church, but felt that 'the political unsettlement which might last a little longer', was making it a bad time for fundraising.

Lord Henry Bentinck, by now an MP again, spoke of the problems posed by new suburbs, saying that the welfare and happiness of the many depended on landowners and developers. He regretted that they had 'a good deal on their consciences in this respect in the past', but felt that people were beginning to learn 'to lay out suburbs in which all classes could live'. He confessed that he was one of those always rushing about in motor-cars, but would nevertheless remember Earl Manvers' words when he heard a church bell on Sunday morning. The Rev. J. H. Taylor repeated his earlier praise of Lord Manvers: 'It was owing to his generosity, and that of Mr Wm. Player and another gentleman present, that they had not had to wait indefinitely.'

The new church, reported the Guardian, would vary little in detail from the plans published in the previous summer. It was to be in Decorated Gothic style, of red brick with stone dressings; length over nave and chancel would be 120 feet, and width across the transepts 62 feet. Roofs of nave and chancel were to be at the same height, 'to lend greater dignity to the interior'. F. E. Littler, the architect, is not much remembered nowadays, but his death in 1930 was marked by respectful obituary notices. Apart from St Christopher's church and vicarage, his buildings included a number on the Duke of Newcastle's Clumber estate, and St Stephen's vicarage, Bobber's Mill Road. Littler also carried out church restorations at Old Basford and Colwick. A diocesan lay- reader for 25 years, he had been an active worker for home and foreign missions. His home was at Lowdham.

It is interesting to note that, as long ago as 1910, the menace of mass motoring was so astutely recognised by Earl Manvers. His comments on the type of service likely to appeal most to the working classes would, however, have been unlikely to find favour with High Churchmen in Nottingham and further afield. Indeed, it is hard to escape the conclusion that there had been a conscious change of direction, influenced by the Earl, from the style of churchmanship formerly followed at the Meadow Lane mission church, and which still flourished at Sneinton parish church. In one report, the Nottingham Guardian described Mr Taylor as curate-in-charge at St Christopher's, but later amended this by pointing out that he was licensed as chaplain to Lord Manvers. The Earl was still patron of the living of Sneinton, and would remain so until 1921; in 1910, it should be emphasised, St Christopher's mission district was still part of Sneinton (St Stephen's) parish. Years before, at his coming-of-age celebrations in 1875. Earl Manvers, then Lord Newark, had heard a speech delivered by the Rev. Samuel Reynolds Hole of Caunton; later Dean of Rochester. Hole spoke of some of the difficulties of being a Lord: 'They expected him to glow with health and spirits, to be a staunch Conservative and an advanced Liberal. Many of them thought that he ought to be a High Churchman, and many of them that he should be a Low Churchman, and have large sympathies with the Nonconformists ....' Both the Earl and his father had supported in their different ways the mission churches in Meadow Lane and Colwick Road, and had taken steps to ensure that places of worship existed where their tenants lived. Nevertheless, one wonders, 83 years after the event, whether some feathers had been ruffled; the apparent absence, from both the foundation stone-laying and the consecration of the new St Christopher's, of clergy from the Sneinton Anglo-Catholic churches of St Stephen, St Alban, and St Matthias, is a striking one.

Another intriguing feature of the occasion was the reference to 'another gentleman present', who with Lord Manvers and W. G. Player was a leading benefactor of the new church. Most readers will recognise the name of William Goodacre Player, of Lenton Hurst; he was a member of the famous Nottingham business family, and a director of the Imperial Tobacco Company. I do not know who the anonymous donor was, but listed in the newspaper report of the ceremony, along with clergy, diocesan officials, civic heads and St Christopher's worthies, were at least two substantial citizens who took an interest in church affairs. Henry Edward Thornton of the Ropewalk was a prominent banker; his obituary would describe him as an earnest churchman, with a commitment to the Church Missionary Society. William Bradshaw of The Park was sometime proprietor of the Nottingham Journal, and had been active in running of the General Hospital, General Dispensary, and Adult Deaf and Dumb Association. When St Christopher's became a separate parish, Bradshaw, together with Earl Manvers and Player, was one of the trustees of the patronage of the living.

Considering that the foundations were laid only in January 1910, it was remarkable that the new church was ready for its consecration by December 1. The district which it would serve stretched from Sneinton Dale to London Road, and crossed the river to include the 'Hook'; this would be the parish when it was constituted. In years to come, the first part of St Christopher's parish to be transferred to another church - St Saviour's, Arkwright Street - was that area of Meadow Lane lying beyond the Midland Railway bridge, now Lady Bay bridge. This included the site of the first St Christopher's, and the streets it was built to serve. Back to 1910, however; the Nottingham Guardian of December 2 indicated just how inadequate the iron buildings had become. So many children were attending Sunday School that they filled the parish room and the new Meadow Lane mission hall, making it necessary for Sneinton Boulevard Council Schools to be pressed into service. Since the opening in 1907 of a permanent church building fund, £5,000 had been raised, 'by the devoted gifts of the poor and the generosity of rich friends'. The new church met with The Guardian's approval; being 'an imposing edifice' in the Decorated style. 'The interior is lofty and well lighted, and, architecturally, its beauty is heightened by the slenderness of the columns and the delicacy of the arches of the aisles, while the transept arches are a feature. The height of the church is very apparent, the nave having a clerestory, and the chancel arch being taken to the full height of the building'. The oak chancel furniture, and panelled walls, came in for special comment, as did the terrazzo flooring and black marble chancel steps. Also noticed were three small windows below the west window; these had stained glass given by parishioners, depicting Christ, St Nicholas, and St Christopher. So energetic had the congregation been in raising money, pointed out the report, that all the furniture was permanent.

A large assembly was present for the consecration service, whose ceremonial was affected by bad weather; rain prevented the procession of choir and clergy round the church to the south porch, and the knocking on the door for admission by the Bishop of Southwell, Dr Edwyn Hoskyns. In his sermon the bishop spoke of the development of the neighbourhood: 'They had witnessed growing around that district street after street, the massing together of a huge population, citizens of a great Midland city, and citizens of a mighty empire.' Paying tribute to the contributions made towards St Christopher's by working men and women in what were difficult times, he declared that their spirit had aroused the sympathy of the Nottinghamshire Church Extension Society and the Spiritual Aid Society, both of which had offered substantial sums. St Christopher's was an example of rich and poor working together, and it had inspired a similar effort in the Meadows, where St Faith's was taking shape. Touching on the problems of city communities, Bishop Hoskyns had long been surprised 'that far more of the wealthy people in Nottingham had not seen long before the great need for careful thought concerning the condition under which the people round them lived.' What Church-people had to do, he believed, was 'to present to the country the true ideal of Socialism, Socialism which should not create anger and hatred between class and class, but Socialism which should create a real brotherhood between man and man, Socialism which should lead the rich to care for the poor and the poor also to care for their brother.' It was, he said, the duty of the Church to ensure that it was present to minister to the needs of all growing communities; compared with East End of London, however the Church in Nottingham was greatly understaffed. 'It was impossible for one man, however good and energetic, to visit from house to house, and to know his flock, when he had between 8,000 and 9,000 people in his district.'

THE NEW PERMANENT CHURCH, from a postcard of c. 1909. (Courtesy Nottinghamshire Local Studies Library).

THE NEW PERMANENT CHURCH, from a postcard of c. 1909. (Courtesy Nottinghamshire Local Studies Library).At the parochial tea which followed, Earl Manvers said what a happy day this was 'for New Sneinton and for him'. He congratulated the builders of the church, William Crane Ltd., and F. E. Littler, its architect. Lord Manvers was confident of St Christopher's future, once more expressing pleasure in the fact that working men took such an interest in it; some had 'actually in their leisure hours, taken a hand in the digging of the foundations'. If working people elsewhere took an equal interest, he asserted, there would be fewer empty churches, and, echoing the view he had expressed at the foundation stone-laying, hoped that 'the service at St Christopher's would always be what the working man loved, simple and devout.' On a more mundane level, the Earl apologised for the absence of the Countess, owing to the bad weather. Bishop Hoskyns again paid tribute to the efforts of the ordinary people in getting the new church built, and had warm praise for 'the spirit of their pastor'. Warming to his earlier theme, he repeated that the new St Christopher's exemplified 'the kind of Socialism they needed to spread - the real friendship and relationship which existed within these walls.' He ended by thanking Lord Manvers for all that he had done. 'Although Lord Manvers would say exactly what the Duke of Portland had constantly said, that wealthy men, and men owning land, had no right to receive those privileges if they did not accept the responsibilities.'

Rich and poor alike having been given plenty to think about, the permanent church of St Christopher's began its career. By the summer of 1911 it had become a separate parish, and the Rev. J. H. Taylor its first vicar (technically its perpetual curate). Its history since 1910 is a lively and eventful one, which must be told at a later date. As we heard at the very beginning of this short account, even the destruction, on one night in 1941, of the church, its iron predecessor, and the Meadow Lane mission room, could not put a full stop to the St Christopher's story.

FOR ACCESS TO PRINTED AND MANUSCRIPT SOURCES, I am grateful to Nottinghamshire Archives Office, Nottinghamshire Local Studies Library, and Nottingham University Department of Manuscripts. The vicars of St Christopher's and St Stephen's, Sneinton, the Rev. Ian Blake and Father Derek Hailes, have very kindly let me have the run of their church safes in search of information. I have also received help from John Redfern at St Christopher's and Joyce Hather at St Stephen's. My best thanks to all of these. This brief history is dedicated to my mother, and to the memory of my father, who were married at St Christopher's on March 2 1935.

[The Editor is grateful to magazine subscriber Brian Lawrence of Buxton who kindly provided the postcard from which the leading photograph was copied, and which sparked off the Author's further researches, already in embryo over a number of years].

* the Nottingham Daily Express stated that the building was of zinc, lined with deal

< Previous