< Previous

SOUTHWELL ROAD TWILIGHT :

A street on the brink of change

By Stephen Best

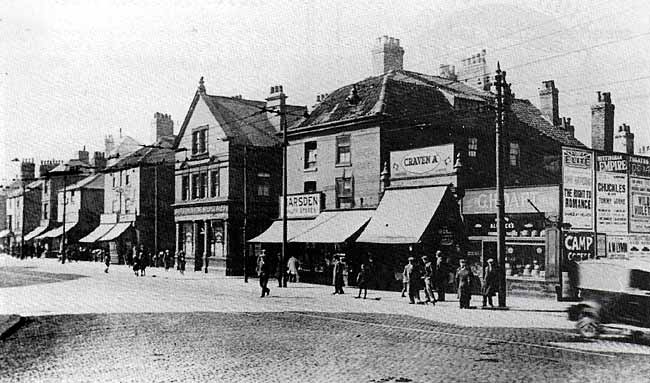

THIS SOUTHWELL ROAD SCENE might have been lost without trace, but for the Nottingham Health Department's exemplary practice of photographing areas to be cleared under Improvement Schemes. We owe much to those who had the foresight to record such views. The photograph is reproduced by kind permission of Nottinghamshire Local Studies Library, Angel Row.

THIS SOUTHWELL ROAD SCENE might have been lost without trace, but for the Nottingham Health Department's exemplary practice of photographing areas to be cleared under Improvement Schemes. We owe much to those who had the foresight to record such views. The photograph is reproduced by kind permission of Nottinghamshire Local Studies Library, Angel Row.HERE, ON A PLEASANT SUNNY DAY in the last week of March 1934, the north side of Southwell Road is captured by the camera. Within a very short time, this scene was to be changed almost out of recognition.

Of all the buildings fronting the street, only the Fox and Grapes public house would survive the year, all the others being swept away in the redevelopment of the Sneinton Market Clearance Area. This had been a target for improvement for many years, and in March 1931, the City Council had announced its intention of pulling down the narrow streets, composed of insanitary and worn-out back-to-back houses, which lay between Southwell Road and Gedling Street. Demolition began later in 1934, and Nelson Street, Pipe Street, Lucknow Street, Brougham Street, Sheridan Street, and Finch Street were almost totally razed to the ground. In December 1935 the Council adopted a plan for the new Wholesale Market, whose avenues were built where the old streets formerly lay. The name of Nelson Street was allowed to remain, but the other names were in due course succeeded by the uninspiring and functional-sounding Avenues A, B, and C; the easternmost avenue was a least dignified by the name Freckingham Street, after the chairman of the Council’s Markets & Fairs Committee.

The premises seen here dated mainly from the early 1820s, and were built across the southern ends of the blocks of back-to-back houses in the six streets, which appear as narrow gaps in the line of buildings. The name Southwell Road was introduced about 1849, the street having been known before that date as Old Glasshouse Lane, and earlier still as Glasshouse Lane. This name came into use in the seventeenth century, one of the town's glass factories being close by. Although a Fox and Grapes pub had been on this site for over a hundred years, the building in the photograph had replaced the original one in the second half of the nineteenth century. It is, of course still in business today as the Peggers Inn, though no longer a Shipstone's house, as it was in 1934. The licensee at the time was Edgar Towlson, who kept the pub for about fifteen years between the wars.

A useful little row of shops was lost when the area was cleared, though many of their regular customers would have gone, anyway, with the demolition of the adjacent streets. On the extreme left of the view, between Nelson Street and Pipe Street, can be seen Wagners & Allsop's pork butchers, and Ashmore's ironmongers. Between Pipe and Lucknow Streets, in a tall, narrow building, is William Taylor's pawnbroking establishment, and the two shops in the low building separating Lucknow Street and Brougham Street are those of Arthur Eyre, butcher, and John Gore, fishmonger. The next pair of shops, lying between Brougham Street and Sheridan Street, are another butcher's, Kingston's, and a pastrycook, John Newton; the latter has a handsome bracketed sign on its front, and the words NEWTON'S OF HOCKLEY painted on the side wall. (Until the demolition and redevelopment of the north side of that street in the late 1920s, Newton's shop had, since the 1880s, been at 31 Hockley.) The Fox and Grapes separates Sheridan Street from Finch Street, and on the opposite corner, in the building with a mansard roof, is a branch of the local grocers and provision merchants, Marsden's. Few parts of Nottingham seemed to be without a branch of Marsden's, and at this date there were no fewer than thirty-four of their shops in the city and suburbs. These included, in addition to the Southwell Road shop, nearby branches in St Luke's Street, Carlton Road, Sneinton Boulevard and Oakdale Road. Next door to Marsden's is Edwin Bamford's outfitter's shop. Above Bamford's sun blind is a faded painted advertisement reading CLOTHING, SHIRTS, HOSIERY, BOOTS & SHOES, FANCY GOODS. From this point the shop buildings take on an altogether more temporary look as we approach the next corner.

The first of the two lock-up shops in the view is Joseph Flatt's tobacconists, with a prominent 'Craven A' advert on top of its pompous little parapet, and an advertisement for Robin cigarettes on the window. Nearer the camera is George Harold Daft’s hardware and barber's shop. His pole, presumably red and white, projects from the shop front just above his SHAVING sign. The white lettering on his window proclaims Daft to be a stockist of Allcock's fishing tackle, a sideline often carried on by gents' hairdressers in and around Nottingham. Beyond, and just out of our picture, lay the original Sneinton Wholesale Market, moved here from the Great Market Place at the turn of the century, in the face of much opposition on the part of the traders, and housed in a series of ramshackle sheds. At the time of the photograph forty-four fruit, vegetable, fish, game, and poultry merchants had permanent standings here.

Of the shops pictured, the one established for the greatest time in Southwell Road premises was Taylor's. This family had conducted a clothier's and pawnbroker's business at no. 11 since the mid-1870s, when they had taken over from another pawnbroker, named Wagstaff. Taylors also had premises in Sneinton Road and Carlton Street, the latter still in business in 1994, displaying Nottingham’s last authentic pawnbroker's sign of three brass balls. Of the others, Marsden's and Bamford's had been there longest. Many of the other shops had changed hands since the Great War, though the nature of trade done at each address rarely varied over the years. At no.7, for instance, Wagners and Allsopp had been preceded by another pork butcher, Thomas Moore, while Ashmore's had taken over the ironmongery next door early in the twenties from a Mrs Eliza Kate Osgarby.

Just visible above the roofs of Kingston's and Newton's shops is another roof, revealing the existence of a tall building lying between Nelson Street and Lower Parliament Street, behind Pullman's extensive cash draper's shop. During the 1930s, Pullman's came to occupy almost the entire block of Lower Parliament Street (formerly Sneinton Street) between Gedling Street and Southwell Road, apart from Mason the pork butcher and Price and Beal's premises at the Southwell Road corner. At the end of the 1930s the tall structure in the picture bore a large painted sign on its west gable: FOR VALUE PULLMAN'S. I think, however, that for many years it had formed part of Kiddier's brushmaking premises, which closed down at this address about 1934.

The advertising hoarding behind the delivery van is rich in interest, and to it we owe the fact that it is possible to date the photograph so exactly. The Elite Cinema in Parliament Street was showing, from March 26 1934, 'The Right to Romance', starring Ann Harding, with Sari Maritza and Nils Asther; the star was playing the part of a woman plastic surgeon: hardly an everyday phenomenon in life at the time. No greater realism is evident in the second feature, 'Chance at Heaven', a romantic story with Ginger Rogers and Joel McCrea. The Elite had for years been Nottingham's most prestigious cinema, but it now had a new rival, in the shape of the Ritz, Angel Row (now the Odeon), opened in December 1933. At the Nottingham Empire in South Sherwood Street was the temptingly-titled 'Chuckles of 1934', led by the Scottish comedian Tommy Lome. If Mr Lome's name fails to ring many bells today, one has to say that his supporting bill also lacked personalities who excite the memory now, despite contemporary publicity proclaiming them to be 'a galaxy of talent' and 'artistes of exceptional ability'. These included another comedian, W.S. Percy: the vocalists Peggy D'Arcy and John Coleman: Cochrane and O'Dette, adagio dancers: and Michel and Nan, described intriguingly in a glowing Nottingham Evening Post review as 'a smart xylophone and dancing turn'. At the Theatre Royal was 'Wild Violets', a musical comedy composed by Robert Stolz in 1932. This 'love story of youth, with music' was set in a sort of Swiss Ruritania, and the Nottingham production was, according to the Evening Post, quite up to Drury Lane standards. Once again, the leading performers stir no special recollections: Vera Pearce, Blake Adams and Phyllis Bourke. Among the supporting artistes were a troupe known as the Seven English Dancers, 'trained by Madame Albertina Rasch'. The show was on each day except Friday, which was Good Friday. Below the Theatre Royal bill is a poster publicising the Spring Meeting at Nottingham Races, held on March 26 and 27; a more sober note is introduced by the one next to this, advertising the services of the nearby, and long-established, funeral directors, A.W. Lymn, of Bath Street and Robin Hood Street.

The van moving out of the picture is one of about 2.5 million motor vehicles then in the United Kingdom; their number was rapidly growing, and the 1930s were to see the number of private cars in Great Britain increase by 100 per cent. Though the road here is virtually empty of motor traffic; the chance of dying in a traffic accident was as high in 1934 as it would be in 1980, when the number of vehicles had risen to around 19 million. In both years there were over 3,000 road fatalities in the United Kingdom. The 30 mph restriction in built-up areas, and the driving test, would not be introduced until 1935, and existing holders of driving licences at that date were exempt from the test. It was comparatively expensive to licence a car in the mid-1930s, a modest 10 horsepower model being taxed at £7.10.0d a year. No public service vehicle appears in the photograph, but there is evidence of two kinds of public transport, in the tramlines and tram and trolleybus wires stretching across the scene. The Carlton tram route had been converted to trolleybus operation in 1931, but the Colwick Road trams would continue to run until replacement by trolleybuses in 1935, the year before the end of Nottingham’s tramway system. The presence of Parliament Street Depot within a few yards of the camera would, in any case, have necessitated the provision of tram and trolley gear in Southwell Road. The overhead wires seen here incorporate electric lighting, high above the middle of the road; much of Nottingham, though, was lit by the familiar gas lamp, an example of which can be seen at the corner of Southwell Road and Finch Street, just in front of Marsden's. The carriageway is of stone setts throughout, the now-universal tarmacadam being nowhere in evidence here. Most bus and tram routes, it might be added, offered a postal service on one late evening journey into the city, and the 9.45 trolleybus from Carlton, the 9.45 bus from Sneinton Dale, and the 9.48 tram from Colwick Road, each carried a posting box, which could be used at any stop. This facility continued until well after the war. Postal deliveries in Nottingham were generous by today's standards, there being four daily deliveries of letters each day: the first at 7am, the last at 4.15pm. At this date it cost three- halfpence to post a letter. This level of provision reflected the comparative rarity of the telephone, Nottingham having in 1934 only some 11,000 subscribers.

At the time of our picture, many manual workers employed by the Corporation were relieved by the recent decision, taken on March 5, to restore from April 1 a wage cut of a halfpenny an hour, which had earlier been imposed upon them. During a debate in the City Council which had resulted in this restoration of pay, Councillor Scott had stated that the extra halfpenny meant to the workers 'the difference between living and existence', while Alderman Green, a great champion of Sneinton, complained that some men employed by the Corporation, who had 3, 4 or even 6 children, were taking home less than two guineas a week. This was, he considered, 'a scandal, and a disgrace to humanity'. The general public, meanwhile, heard, in the week of our photograph, that the City Rate would remain unchanged at 14/2d in the pound. Some of that would be going towards the salary of the new general manager of the City Passenger Transport undertaking; Mr J.L. Gunn had taken over a week or two before the photograph was taken, at a salary of £1,500 a year. Duncan Gray, who was appointed City Librarian in October 1934, was, however, to receive only half as much. Those men who had had the halfpenny docked from their hourly pay would probably have felt that both these chief officers were pretty well off.

The camera has, as usual, attracted some interested spectators. A number of children can be seen, together with a few women, and a white-coated assistant at Marsden's, but the majority of those in the view are men, apparently with nothing better to do than stand about in the street. They should not, however, be dismissed as idlers. These were awful times for men to find work; unemployment in Nottingham in 1934 stood at 12.5%, 14,294 people being out of work. This showed a fall from the disastrous peak of 1931, when 16.9% of the working population in the city were unemployed, but things were still bad enough for a new Unemployment Centre to be opened that very week at Basford, followed by another in July, at Radford. The unemployed had had little to cheer in the doings of the local football teams in the season just ending. Nottingham Forest and Notts County ended the 1933/34 season in 17th and 18th places in the Second Division, both with 35 points. One memorable match had taken place just a fortnight earlier, though it was not the quality of the football that distinguished it; a tremendous cloudburst had flooded the pitch at Meadow Lane, forcing the abandonment of the game. Nor were things any happier at Nottinghamshire County Cricket Club. The 1934 season was to be overshadowed by controversy over the Bodyline bowling used against Australia in 1932/33 by the Notts fast bowlers Larwood and Voce. Amid much rancour, neither appeared in the 1934 test matches, and the Notts captain Arthur Carr was sacked after fifteen years in office. The Trent Bridge test, played some ten weeks after the picture was taken, resulted in a decisive win for Australia with just ten minutes to spare.

For those with the wit to see it, though, a far darker cloud than that of sporting failure was hovering over the people of Nottingham, and indeed of the world. In 1933 Hitler had become German Chancellor, and on the death, later in 1934, of Hindenberg, he was to assume the powers of a dictator. Not everyone, however, wanted to recognise the danger signals. In August 1935 the Evening Post would print the impressions of a party of Nottingham people who had just returned from a holiday tour of Germany. There were, stated the report, no unemployed to be seen in the streets there; all in Germany were engaged in some kind of work, with the sons of barons and counts side by side in the labour camps with working men. Hitler, continued the writer, hindered no religious movements; he had realised that the Jews controlled the finances of the country, so had taken away their power, and distributed their wealth for the benefit of all. He did not interfere in the least with poor Jews, and those who had been causing trouble among them were a lot of hooligans, to be severely dealt with. Finally, wrote the contributor, the Storm Troops were merely a band of men like our Special Constables, who assisted in keeping law and order - an excellent idea we might copy to help our police. In October 1936 just over a year after the appearance of this insolently naive piece of reportage, the swastika flew, alongside the union flag, over the County Hotel in Nottingham in honour of the Stuttgart police boxers who were staying here. Notwithstanding the ability of the British to deceive themselves, the lives of all in the picture who survived until 1939 would be radically affected by events in Germany.

< Previous