< Previous

THE MAKING OF VICTORIA PARK

Part 1 : 'A huge sandy area'

By Stephen Best

BATH STREET CRICKET GROUND and its surroundings, from the 1861 Salmon's map of Nottingham. Development north of Alfred Street was still incomplete, and nearer the ground, neither Bancroft's factory nor Victoria Buildings was yet in existence.

BATH STREET CRICKET GROUND and its surroundings, from the 1861 Salmon's map of Nottingham. Development north of Alfred Street was still incomplete, and nearer the ground, neither Bancroft's factory nor Victoria Buildings was yet in existence. JUST OVER A CENTURY AGO, on May 7 1894, the Mayor of Nottingham, Alderman Frederick Pullman, formally opened Victoria Park in Bath Street. A leading figure in the Sneinton area, and proprietor of a noted drapery business nearby in Sneinton Street, Pullman was well aware of the value to the community of an attractive open space in a far from wealthy part of the town. The park still serves the neighbourhood, and has recently been re-landscaped and modernised; its story does not begin, though, with Alderman Pullman presiding at its opening ceremony, but goes back many years further. In this short account we follow the day-to-day problems of the recreation ground through the period leading up to its transformation into Victoria Park. The surprising amount of official detail recording the routines and difficulties of this quite small amenity in the latter part of the nineteenth century reflects the complexity and energy of municipal life in Victorian Nottingham.

The earliest mention of a recreation ground on the site is in the 1845 Enclosure Award Map, which names the open space as the Meadow Platt Cricket Ground, and cites the Mayor, Aldermen & Burgesses of Nottingham as its owners. The Enclosure Award refers to it as follows: 'One other allotment or piece of land situate in the Clay Field .... containing four acres and eighteen perches bounded towards the East by Recreation Road, towards the West by St Ann's Cemetery, towards the North by allotment 95, and towards the South by Meadow Platt Road, and which said Allotment 91 now forms and is called the Meadow Platt Cricket Ground....,' Recreation Road was the thoroughfare known nowadays as Robin Hood Street; St Ann's Cemetery is now the Bath Street Rest Garden; while Meadow Platt Road became Bath Street.

The land for the cemetery was given by Samual Fox, a Quaker, after the cholera outbreak of 1832, and was consecrated as St Ann's Cemetery in 1835; it was later officially named St Mary's Cemetery, but often referred to locally as Fox's Close. The forerunner of Bath Street, which was formed alongside it in the early 1830s, was for obvious reasons first called Burying Ground Lane. One man who wrote to the Nottinghamshire Guardian during 1925, however, claimed that in his youth the place was also known as Pipeclay Hill.

Following the Enclosure Act, the land to the north and east of Bath Street became fairly rapidly built up, and from the position of a playground on the edge of open country, the Meadow Platt Cricket Ground took on the character of an urban open space. Its status as a place for games and relaxation is confirmed by a couple of entries in the minute book of the Corporation's Inclosure Committee during 1857. In May it was recorded that James Whittle, the town pinder, was to receive a sum of money for, among other things, keeping in order the cricket grounds in the Meadows and Bath Street; and in November that the Mayor, Alderman Heymann, wished, at his own expense, to 'put up a Drinking Fountain in the Bath Street Cricket Ground'.

We next pick up the story almost two decades later, when, in November 1876, the Public Works and Recreation Grounds Committee of the Town Council were attempting to improve the ground. A proposal to plant a further row of trees was, however, withdrawn. The following May saw the Committee decide that no one should be allowed to play cricket on 'Bath Street Recreation Ground' within 30 yards of a public highway; we do not know what danger to road users had been caused by flying balls, but there had evidently been some complaints. A mark was to be put in the ground so that 'the policeman shall be able to distinguish whether persons playing are within prescribed mark'. This is the first of a number of minutes to reveal that the recreation ground had its public order problems; however, the myth of a Victorian ideal society in which everyone knew his place, and behaved perfectly within it, is a hard one to dispel. Certainly by the mid-1870s the playground had acquired a new influx of users, with the opening of Victoria Buildings on the other side of Bath Street. As has been described in an earlier issue of Sneinton Magazine, the Buildings were from the beginning plagued by unruly and antisocial behaviour. It is perhaps significant that the Nottinghamshire Guardian correspondent already mentioned recalled in 1925 that Bath Street Cricket Ground was, in those early days, 'a huge sandy area with some swings, but given up generally to a number of rough characters'. 1878 saw the first mention of another problem, the drainage of the recreation ground. New iron grates were installed to take away surface water, one of them near the police lodge; this building, as many readers will remember, stood at the angle of Bath Street and Robin Hood Street, on the spot now occupied by a betting shop. As the reference to the playing of cricket shows, the constable resident at the lodge was expected to keep a sharp eye on the activities of those using the recreation ground. The decade ended with modest improvements; new trees were to be planted, at a cost of no more than £20, and new swings were to be put up, in places to be selected by Councillor Browne. It was decided that up to £50 could be spent on these. The Committee succeeded in keeping within their budget, as their annual report showed; trees planted around the ground at a cost of 'about £20', and eight sets of swings provided for £48.16.0.

THE POLICE LODGE at the corner of Bath Street and Robin Hood Street, with the Bath Inn at the right. A photograph taken in the 1890s.

THE POLICE LODGE at the corner of Bath Street and Robin Hood Street, with the Bath Inn at the right. A photograph taken in the 1890s.The minute books for the 1880s give further glimpses of developments, and of problems which cropped up from time to time. Poor drainage continued to cause concern, and in 1882 it was found necessary to fill with rough cinders the gutter made by storm water at the back of the boundary wall. Games were still being played 'in dangerous proximity to the adjoining highways', and the policeman occupying the lodge was asked to see that this practice was stopped. The following year saw money laid out on the provision of two stone steps for the entrance, and on iron posts to stand at their head. The posts, costing £12, did not have far to come, being made by Cowen & Co. at the Beck Foundry in nearby Brook Street. Meanwhile, Arthur Brown, the Borough Engineer, was asked to tell the Committee what methods he would propose for improving the recreation ground.

The next upheaval was caused by the arrival on the scene of the Beck Valley Storm Water Culvert. This was one of the public works constructed to improve the drainage of a Nottingham still subject to outbreaks of water-borne diseases rife in areas where the sewerage systems were ineffectual. The Beck Stream flowed underground from St Ann's Well, down the course of St Ann's Well Road, along Brook Street, and Manvers Street; though it had, from the time it was culverted, been used as a sewer, it was hopelessly inadequate. St Ann's Well Road was subject to frequent flooding, and the need for a replacement sewer was clear. The Beck Valley Culvert was therefore planned to follow the course of the stream from near the bottom of St Ann's Well Road, then to bear off to the east under the site of the present-day St Catharine's church, the adjacent burial ground, and the Bath Street Cricket Ground. It then crossed Bath Street, and went beneath Sneinton market; its outfall to the River Trent is at the end of Trent Lane in Sneinton. The first mention in the minute books of the consequent engineering works was when Mr Barry, of Foster and Barry, contractors for the culvert, attended the Public Parks Committee meeting of November 21 1883, asking to rent about 1,000 square yards of the cricket ground, for the erection of stores for materials needed during the course of the works. It was resolved that this land be let to Foster & Barry for 50 guineas. This work was to provide the recreation ground with a feature which survives to this day, and which puzzles many passers-by. This is the curious little stone tower, which stands close to the boundary wall with the old cemetery. Of handsome architectural brickwork, it was until recent years smothered in ivy. It is believed that the tower was originally an access shaft to the Beck Culvert tunnel during its construction, though it became a ventilation shaft for the culvert, foul air being carried up the shaft, and out through a grille at the top.

Meanwhile life carried on much as before in the recreation ground. In April 1884 the Committee received a letter from a Mr George Reed, complaining of the danger to foot passengers from stones being thrown out from the 'Robin Hood Street Cricket Ground'. The Committee, no doubt sick of hearing about such misbehaviour, declared that they could do nothing about it, and that it was a matter for the police. A little later that year, on July 16, it was recorded that, in response to repeated complaints on the subject, the Chief Constable had stopped men from playing cricket on the ground. Children and youths were still to be allowed; as an upper age limit of thirteen was to be set, however, it seems that a very restrictive definition of 'youths' was in force. One highly respectable group made use of the recreation ground in June, when the Hockley Society of Primitive Methodists were allowed to hold a camp meeting on Whit Sunday. In addition to his concerns about the activities of over-age cricketers, the Chief Constable voiced apprehension over the state of the public seats; it was decided that nothing would be done about these until the sewer works were completed. The swings, though, were repainted and put in proper repair. A further high-minded Victorian activity is recorded in 1885, a Band of Hope Union Demonstration being given permission to muster at several parks on May 18; Bath Street was one of these, together with the Meadows and the Forest. By July 1885 work on the Beck Culvert was finished, so Foster and Barry were requested to move the stores building they had put up eighteen months or so earlier. The Borough Engineer was again asked to prepare a scheme for improvements to the ground; presumably he had been obliged to wait until the disruption caused by the culverting had ceased.

If the Committee hoped that the cricketing nuisance had been controlled, they were disappointed to receive in May 1886 a letter from a gentleman named as the Rev A. M. Greenhalgh (probably the Rev. A. G. Greenhalgh, curate of St Paul’s, George Street), drawing their attention to acts of trespass in St Mary’s Cemetery (as it was now called), 'from persons playing cricket on Bath Street Recreation Ground.' As before, the Committee considered that this was not their problem, recommending that Mr Greenhalgh be referred to the Chief Constable.

By autumn, however, Bath Street was providing the Public Parks Committee with more than enough to think about. On September 20 1886 Councillor Lees, leading a deputation of local people, attended the monthly committee meeting. Their first complaint concerned the rainwater and dust which, depending on the nature of the weather, flowed or blew off the ground on to neighbouring streets; the Committee, again seeking someone else to hold responsible, decided that owners of houses in Promenade be asked to undertake the necessary street works to end this nuisance. The deputation also alerted the committee to 'the purposes to which, owing to its badly lighted state, the ground was put, and also the damage done by boys to the trees in the ground.' Quite what these mysterious goings-on were can only be surmised, but one suspects that the place was the setting for the sort of amorous activity which has always characterized ill-lit parks. At all events, the Committee determined to ask the Lighting Committee for a large lamp, placed on or near the recreation ground; Councillor Lees stated that he would be willing to confer with the appropriate authorities about the siting of this. The poor Chief Constable was again requested to pay special attention to the ground, to stop mischievous damage to trees. Finally, the Borough Engineer was to be asked to think of a way to stop water from running off the ground and flooding the road outside. 1886 ended with an order for the lamp to be put up and protected from vandals.

In 1887 there was a change of landscape gardener responsible for the maintenance of Bath Street Cricket Ground. (An official title for it seems never to have been fixed upon, and I have repeated the variations of name as they occur in each report or minute.) Hitherto Frettingham & Son, of Bromley House, Angel Row, had looked after all public walks and recreation grounds in the Borough. Now, with their number ever increasing, it was decided to split the job into three contracts. The one which included Bath Street went to W. Bardill of Stapleford for an annual fee of £369. Frettinghams retained responsibility for what must have been the most prestigious and challenging job of all, the Arboretum, and were paid £750 for it. The state of the Bath Street ground continued to cause concern, and in April 1888 the Borough Engineer was again asked to report on its condition, and to recommend what should be done. Early in the following year the Engineer was told to go ahead with improvements to the drainage, for which £120 had been earmarked. In March 1889, however, when he laid his plan before the Public Parks Committee, it was decided that consideration of it should be held over. A further postponement was agreed upon in July, and the decade ended with the feeling that all was far from satisfactory at Bath Street, and that something quite radical would have to be done about it.

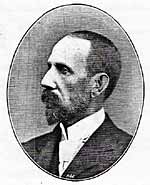

ARTHUR BROWN, the Borough Engineer, who was responsible for the design of Victoria Park.

ARTHUR BROWN, the Borough Engineer, who was responsible for the design of Victoria Park.The 1890s found the same old problems besetting the recreation ground. In February 1890 the Watch Committee were asked to make sure that the police gave special attention to the way games were played there, in view of complaints 'from inhabitants of neighbouring houses'. Bardill, meanwhile, was ordered to clean out the gullies adjoining the police lodge after every heavy fall of rain. Surface drainage was clearly still a serious problem, and in 1891 the Public Parks Committee again addressed the question of major improvements. Interested local people were invited to submit suggestions as to what was needed, and in June Councillors Sharkey (who led the campaign for a modernised park) and Gregory presented to the Committee a memorial signed by 557 residents, begging that consideration be given to improving the site. After an official inspection, the Public Parks Committee yet again threw the problem at the Borough Engineer, who was to prepare a plan and estimate for levelling and draining. This was quickly made ready, and laid before the Committee in July; they, however, noting that the cost would amount to £2,300, immediately stated that they could not undertake such expenditure. At a full meeting of the Borough Council on October 5 1891, Councillor Sharkey, seconded by Councillor Gregory, moved a resolution that: 'It is desirable that a scheme should be devised for rendering the Bath Street Recreation Ground better available for the purposes of recreation, and that a Committee be appointed to devise such scheme, and to report to the Council'. After more official passing of this hot potato, the hapless Engineer was once more instructed to prepare a report on the levelling and draining the ground, asphalting it after levelling, and planting trees and shrubs along the north and west boundaries. At last Arthur Brown's labours were not in vain, and over the following year a redesigned park began to take shape.

Part 2 will relate how the new recreation ground was at last created and opened.

< Previous