< Previous

'THE RAPID RIDE':

A guide-book journey on Sneinton's first railway

By Stephen Best

The front cover of ’THE TRAVELLER'S HANDBOOK'.

The front cover of ’THE TRAVELLER'S HANDBOOK'.The first railway to link Nottingham with places to the east of it was opened in 1846; this was the Midland Railway's line to Lincoln, which connected that city with the routes already serving Nottingham, Derby and Leicester. Since the drastic pruning of the network of railways serving Nottingham, this route has once again been the only line leaving it in an easterly direction, though it nowadays carries traffic for the former Great Northern route to Grantham and beyond, which diverges from the old Midland line at Netherfield Junction.

Lincolnshire is usually thought of as a Great Northern or perhaps a Great Central Railway stronghold, and it comes as something of a surprise to be reminded that the Midland was the first line to reach it. The Midland set much store upon its penetration into the county, and indeed Lincoln was one of six towns served by the Midland whose heraldic devices were included on the Midland Railway coat-of-arms. Nottingham, which might be thought to have had a greater claim, was, oddly, not represented, though the Nottingham Borough arms had appeared on the device of the Midland Counties Railway, which became part of the Midland in 1844.

No sooner had the line opened than the Lincoln printer and bookseller James Drury hurried into print his Traveller’s Hand-Book for the Lincoln and Nottingham Railway; describing in an attractive and pleasing form the towns, villages, scenery, &., during the rapid ride'. The line from Derby to Nottingham had already been the subject of a guide, but the little booklet just mentioned also possesses its own special interest, describing as it does for the first time the railway approaches to Nottingham through Sneinton and the land now undergoing redevelopment. The booklet bears no date, and there are indications in it that its writer was unfamiliar with some of the ground he purported to cover.

In his introduction, the author remarks that railway travelling afforded ample scope for reading, and recommends the guide as an inexpensive additional luxury on the journey. He hopes that it will also contain information of use to travellers, since 'Ladies in particular are inconvenienced by a want of knowledge of the arrangements at Railway Stations, and in passing from one train to another, frequently are the victims of errors, which prove a source of great annoyance and vexation.'

Following an historical account of the City of Lincoln and a lengthy description of its more picturesque sights, the booklet turns its attention to St Mark's Station, situated, so it states, not too far away from the business and a trading part of the city, but where 'the bustle and confusion necessarily consequent upon the arrival and departure of trains, clashes as little as possible with the business arrangements of the City'. The station would, when completed, be one of the most prominent attractions of Lincoln, the writer considering that it possessed much architectural merit, and far surpassed Nottingham Station in commodiousness. (We shall come to the latter in due course).

The description of the journey begins with a feverishly romantic bit of scene painting; at Lincoln Station, the porters 'are running to and fro with the agility of young fawns', while late arrivals are literally bundled into the carriages. The signal having been given, 'the ponderous machine glides on, and the traveller scarcely feeling a sensation of movement, soon finds the Station disappearing in the distance.' The scenery on either side of the line is described, with comments on the historical associations of each place passed. The stations at Hykeham, Thorpe-on-the-Hill and Swinderby are noted, as the train passes from Lincolnshire into Nottinghamshire.

The first stop in the county is made at Collingham, and, a mile or two further on, we are presented with a puzzle, the booklet stating that We have now arrived at Winthorpe Station'. The train might well, indeed, have reached the spot intended for this facility, but one wonders whether a station was ever built here. The timetable until the end of 1847 lists Winthorpe among the stops on the line, but no trains are shown as calling. A timetable for the Nottingham- Lincoln railway in the 'Nottingham New Family Journal' for March 1851, however, makes no reference to Winthorpe, which seems to have been one of Nottinghamshire's ghost stations. The original timetable for the line, incidentally, lists Hykeham and Collingham stations in the same way as it does Winthorpe, with no indication that any train was yet serving them.

The description of the route now reaches Newark. There was no flat level crossing of railways there to be negotiated in 1846, the Great Northern Towns Line' between Peterborough and Retford not being opened until 1852. The Midland Station (now Newark Castle) was still in the course of building, but according to the Guide, 'when complete, will be a very handsome and commodious building'. As one might expect, the many historical associations and sights of Newark are recounted in detail, before the description of the line to Nottingham begins. There was no station at Rolleston then, and the next stopping place was at Fiskerton: 'Here the traveller intending to go to Southwell alights, and the town being at some distance, there are always two cabs waiting the arrival of the train.' (A railway passenger from 1846 would, if he could return, once again have to get off here for Southwell, but would probably be disappointed by the connecting transport now provided, or not provided, in the 1990s). The booklet deals at length with the history and architectural glories of Southwell before the journey to Nottingham is resumed. Between Fiskerton and Bleasby, whose station was to be built some years later, the train, according to the author, passes 'over bridges crossing the Trent'; it is to be hoped that no passengers ricked their necks in looking for these castles in the air. Its next stop was at Thurgaton (sic), a village possessing 'a curious looking Lilliputian church'; the history of Thurgarton and Gonalston is recounted before the arrival of the train at Lowdham Station. Discussing Lowdham, and the neighbouring villages of Calverton and Woodborough, the writer gives an account of the Luddite disturbances which had occurred in the neighbourhood thirty years earlier.

Burton Joyce was the next stop, 5.5 miles from Nottingham, and the booklet deals with the associations of villages opposite Burton Joyce on the south side of the Trent; Shelford, Bingham, and Redcliffe on Trent (sic). Gedling and Mapperley, next passed by the train, are dismissed by the author as 'of no great significance'. Carlton, however, the location of the penultimate station on the Nottingham line, is characterised as 'an extensive village, containing about one thousand five hundred inhabitants, who are mainly employed in the manufacture of hosiery'. Scratching about to find something of historical interest to say about Carlton, the writer has to fall back on the fact that it was in the honour of Tutbury, and entertains his readers with anecdotes of Tutbury Castle, and, by the slenderest of connecting threads, of Oakham Castle. The train then ran along the foot of Colwick Woods, the writer of the pamphlet meanwhile beguiling passengers with an anecdote concerning a mishap which befell the father of Squire Musters of Colwick Hall one day when his horse bolted. Abruptly becoming very up-to-date, the writer comments: 'All along the line the traveller will have observed the wires and posts of the Electric Telegraph. The wonderful rapidity and correctness with which intelligence is communicated by this great triumph of modern art - the fact that persons through its agency can hold, as it were, conversation, need not now be dilated upon, as scarcely any person is ignorant of the construction of and the mode of working the instrument.' The sceptical reader, both then and now, could be forgiven for smelling a rat; one suspects that a great many people did not understand the workings of the electric telegraph, among them, perhaps, the author of the booklet, who wriggled out of an explanation by means of this flimsy literary device. There are times, during the reading of this booklet, when one suspects that its author wrote the description of the journey before the line had actually opened, so as to achieve publication on the inaugural day; the account of the opening which appears in the ’Nottingham Review', however, clearly states that the erection of telegraph posts and wires between Nottingham and Lincoln 'will be commenced this week', so it seems that the writing was in fact done a little later on.

The train was now running past Sneinton, to which the booklet devotes quite a detailed paragraph; as it is our earliest glimpse of Sneinton from the railway, it deserves to be quoted at length. 'Emerging from the cutting, the large suburban village of Sneinton suddenly bursts upon the view, with numbers of beautifully cultivated private gardens. Not many years have rolled past since the village consisted only of a few scattered houses inhabited by a population not exceeding three hundred persons: now it boasts several streets and many elegant houses, and has a population of at least two thousand. The newly erected church is dedicated to St. Stephen, and the living is in the patronage of Earl Manvers. The County Asylum for Lunatics, a commodious brick building capable of affording accommodation for one hundred and forty patients, is situated in this village; the establishment is reputed to be exceedingly well conducted and it is supported by the voluntary contributions of the affluent. In the rocks, as the traveller sweeps along, he will perceive some curious excavations, used as human habitations; these singular dwellings are called the Hermitage of Sneinton, from the supposition that formerly they were inhabited by hermits. But the greatest singularity is that there are two tiers of houses, the upper row being reached by a flight of steps cut in the rock. A large fall of rock happened in 1839, but providentially no lives were sacrificed though several of the houses were buried. The place has several large commodious rooms used upon occasion of rejoicing, such as wakes, for dancing and other modes of festive celebrations.'

Though the above account is not perfect, it must be conceded that many less accurate pictures of Sneinton have been published over the years. The General Lunatic Asylum stood on land now occupied by King Edward Park, and was indeed notably well run on extremely humane lines; it was not, however, visible from the railway. Nowadays Green’s Windmill would probably be the first object of interest to be mentioned; in 1846 it would have been as prominent on the skyline as it is today, but windmills were at that date, in common parlance, ten a penny, and not considered worthy of comment. George Green, who had been dead for five years, and of whom the writer had probably never heard, was not mentioned, either. The rock fall described by the writer occurred, by the way, not in 1839, but ten years earlier, on April 13 1829.

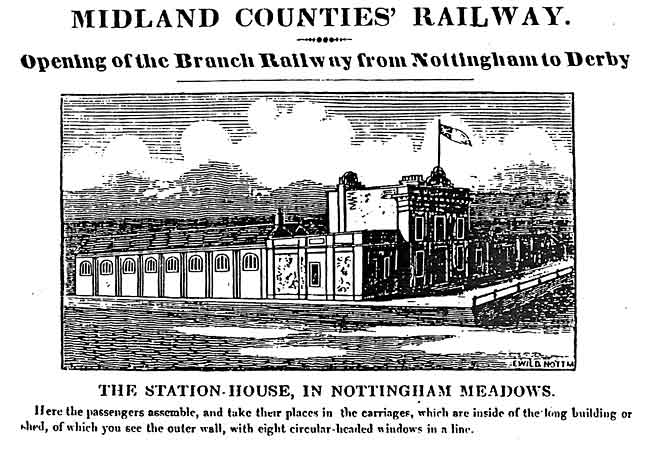

NOTTINGHAM’S FIRST RAILWAY STATION, as depicted in the Nottingham Review on its opening in 1839. Trains to and from Lincoln used it from 1846 to 1848.

NOTTINGHAM’S FIRST RAILWAY STATION, as depicted in the Nottingham Review on its opening in 1839. Trains to and from Lincoln used it from 1846 to 1848.Next to be described is Nottingham Station; this, according to the booklet, was 'approached wider a magnificent bridge of several arches, also erected at the expense of the Company. This was the bridge carrying the Flood Road (now London Road) over the line; nowhere else, though, does one find it described so glowingly, and once again the suspicion is aroused that the writer had never actually seen the structure he praised. The Flood Road bridge was built in the teeth of objections by the Town Council, who complained that such a structure would impair the view of Nottingham from the south enjoyed by those approaching it along the Flood Road. The Council's attitude over this bridge appears wilfully awkward in the light of its opposition to the level crossing at Queen's Road, as the stretch of Carrington Street south of the canal was then named. The Lincoln line thus came into use with crossings of Nottingham's two exits leading to Trent Bridge; a level crossing at a place where the Council demanded a bridge, and a bridge over the line where the authorities wanted a level crossing. The bridge over the railway at Queen’s Road would not materialise, however, until as late as 1869.

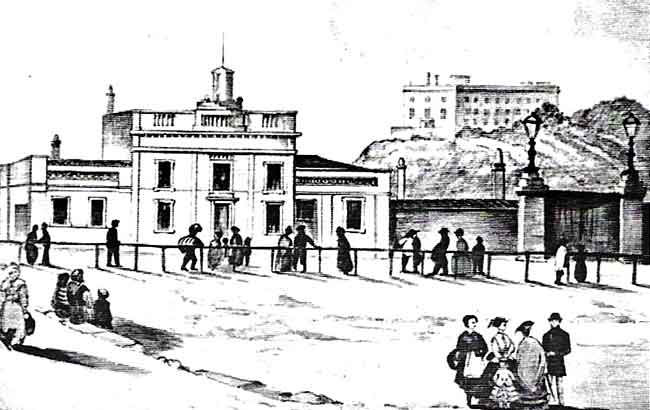

It may at this point be useful to summarise the early siting of Midland lines in the town. The original railway from Derby to Nottingham had terminated in 1839 at a station west of the present Carrington Street, and on the south side of the canal. This was difficult to reach from the town, and the Council were prevailed upon to build Carrington Street canal bridge in 1841-42. This was adequate as a means of access to the 1839 station, but the extension of the railway to Lincoln meant that tracks had to cross the newly constructed Queen's Road, opened to convey Queen Victoria and Prince Albert away from the first station and out of Nottingham on their brief visit to the town in December 1843. For over twenty years the Queen’s Road (later Carrington Street) level crossing was to prove a severe obstacle to road traffic in Nottingham. Inhabitants of Lincoln, that most level-crossing bound of cities, may, however, on reading this, be forgiven for thinking that Nottingham people made a fuss about very little.

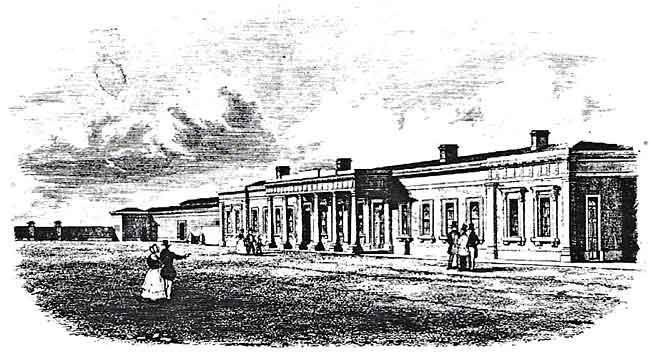

THE FIRST STATION stood to the west of what is now Carrington Street, and south of the canal. A wash drawing of c. 1840.

THE FIRST STATION stood to the west of what is now Carrington Street, and south of the canal. A wash drawing of c. 1840.The writer of the pamphlet indulges in no false praise about the station: ‘the Station itself requires no particular description, travellers being well acquainted with the general features of these adjuncts to the modem mode of travelling: suffice it to say that, in the construction the useful has been more considered than the ornament, and that the Nottingham Station as far a effect is concerned, falls far short of Derby and other similar erections.' It is surprising that no mention is made of the single most inconvenient feature of the working of the station, the necessity for trains to reverse in and out of it on their way to or from Lincoln. This soon proved to be an intolerable nuisance, and an extra platform was provided along the southern side of the terminal station, allowing through running. This, however, was to be a very temporary measure, as it was quickly realised that a new station was needed. Opened in 1848, it had a frontage in Station Street, and remained Nottingham’s Midland Station until the erection in 1904 of the grand buildings on Carrington Street bridge.

The author states that the architectural shortcomings of Nottingham Station; were more than made up for by the splendid prospect afforded from it: ‘On the one hand the magnificent church of St Mary towering above the surrounding buildings presents an attractive spectacle; in the front is the London road, and beyond, the wood- crowned hills of Colwick form pleasing objects in the landscape. The luxuriant meadows stretching down to the margin of the serpentine Trent, the new church of Sneinton, the rocky Hermitage of Sneinton, and the hills of Ruddington, round which the London road winds, may also be seen from the Station, and passing through the long shed used as a covering for the Railway carriages, a magnificent picture bursts upon the view of the traveller, comprising the greater part of the town, with the churches of St Nicholas and St James. Beyond is seen the bold rock upon which stand the ruined walls of Nottingham Castle, inaccessible on all sides except that next the town.' It would surely have been hard for anyone, even citizens of so historic a place as Lincoln, to resist such blandishments, and the traveller would be further enchanted by tales of Nottingham’s romantic history. The author devotes much space to an account of the capture of Mortimer by Edward III at the Castle and delivers a favourable opinion upon the Great Market Place: ‘One of the most extensive and commodious in the kingdom, and is surrounded with imposing buildings with piazzas.

A footnote advises the passenger from Lincoln that: 'Here the traveller intending to proceed forward, will receive every information on application at the Station: if his destination be DERBY, he will have to pass through Attenborough, past the Long Eaton Junction, &c. &c., and many objects of interest both sides of the line will claim his attention. If he is proceeding to LONDON, he will leave the Nottingham and Derby line at the Long Eaton Junction and will pass through Loughborough and Leicester to the Rugby Station, and thence on the London and Birmingham line to London'. This reminds one that early rail travellers from Nottingham to London had to pursue something of a dog-leg course; by Midland to Leicester, thence over the Midland line from Leicester to Rugby (closed in 1962) and finally by the London & North Western from Rugby into Euston.

Assuming his readers’ intentions of travelling beyond Nottingham, the booklet’s author takes his description of the route to the western outskirts of the town. The Park is noticed on the north side of the line, 'with the Barracks at one extremity, and a Bowling Green at another'. The Barracks were to be demolished in the 1860s, but the bowling green still exists. Mention is also made of the caves, known as the Druid or Papist Holes, in the face of the sandstone cliff above what is nowadays Castle Boulevard. These were visible 'shortly after the gate-keeper's lodge at the crossing of the Wilford road is passed'. This crossing would remain in use until 1861, when it was superseded by a bridge. The name ‘Druid Holes’ provides the excuse for the author to indulge in some picturesque inaccuracies about Druids and their associations with the site. The crossing of the road to Wilford enables the booklet to point out that village, 'with its church almost hidden in the dense foliage A brief account follows of the poet Henry Kirke White, and of Clifton Grove, before the unnamed writer signs off: 'Having accompanied the traveller thus far on his journey and pointed out all the objects of interest, the publisher must conclude his attempt to amuse, trusting that the little work will meet with the approbation to which the small price and the variety of entertainment offered entitle it.'

One wonders how much of an impact the little booklet did make in 1846, and whether it received the appreciation that its author thought it deserved. One curious omission is any indication of the times of trains; perhaps these had not been finalised by the date the guide went to press? There can be no doubt that the ‘rapid ride’ described by the author would have seemed precisely that to the traveller of the time. Of the five trains in each direction on weekdays, the usual journey time between Lincoln and Nottingham was about 1 hour 50 minutes; this may not appear anything very special, but when one recalls that, in the 1830s, stage coaches generally needed between four and five hours to negotiate the distance between Nottingham and Lincoln, the effect of the train upon England’s travelling public can be understood. The railway age very quickly saw the end of the stage coaches on any route that became served by trains.

That the Nottingham-Lincoln line will ever again be the subject of a guide book must be greatly doubted. Even if it survives the uncertain future which confronts so many railway routes in Great Britain, however, we may feel confident that one observation of the unnamed writer of 1846 will not be repeated; never will porters, if such beings still exist, be seen scurrying about 'with the agility of young fawns.'

AN ENGRAVING OF THE TOWN'S SECOND STATION, sited with its frontage and offices in Station Street. Its position allowed direct through running between Derby, Nottingham and Lincoln. Opened in 1848, it was superseded in 1904 by an enlarged and rebuilt Midland Station, with entrance in Carrington Street.

AN ENGRAVING OF THE TOWN'S SECOND STATION, sited with its frontage and offices in Station Street. Its position allowed direct through running between Derby, Nottingham and Lincoln. Opened in 1848, it was superseded in 1904 by an enlarged and rebuilt Midland Station, with entrance in Carrington Street.< Previous