< Previous

POOR CHAMBERS:

The dramatic death of a Sneinton

man

By Stephen Best

THIS IS A STRANGE STORY, concerning a man whose stay in Sneinton was brief and obscure. But for the extraordinary circumstances of his death, he would be quite forgotten. As it is, little is known about him and his family, and even his exact address cannot be stated with certainty. Still, the tale is worth telling.

Sometime in 1861 or 1862 James Chambers moved to Nottingham from the London area with his wife Rachel and young family. A weaver by trade, he secured the post of teacher in mat-making and weaving at the Midland Institution for the Blind on the corner of Clarendon Street and Chaucer Street, his name appearing in the list of instructors in the Institution’s annual report for 1862.

Chambers's home was variously said to have been in Thorneywood Lane, and 'on the Carlton Road, in the gardens opposite the Sneinton Elements'. This narrows the place down to one of the gardens bounded on the south side by Carlton Road, and on the east by Thorneywood Lane (now Porchester Road). The family had not arrived here when the 1861 census was taken, and had moved away from Sneinton before the next census was carried out in 1871. Although a more precise address appears in no other traceable records, we can place their home very close to where Marmion Road now runs, just a very short distance from the old Thorneywood railway station at the junction of Carlton Road, Porchester Road, and Cardale Road.

This was an interesting piece of land. In the Sneinton Enclosure Award of 1798, a field at the foot of Thorneywood Lane was allotted to the the vicar of St Mary's, Nottingham, and another, much larger, to the curate of Sneinton. During the nineteenth century a number of structures were put up in the gardens which had been cultivated here, and used as dwellings, usually without any proper authorization. Some of the garden-dwellers' addresses reflected the ecclesiastical ownership of the land; St Stephen's Gardens referred to Sneinton church, and Wyatt's Gardens to one of its nineteenth-century incumbents, while Brooks Gardens was named after a vicar of St Mary's. Other names, like Thorneywood Lane Gardens, were self-explanatory.

James Chambers was, therefore, indisputably a resident of Sneinton parish, even if he did occupy one of its more scattered outposts.

In his early-to-middle thirties when he moved from London, Chambers won good opinions from his employers at the Blind Institution. His father had earlier gained a reputation for his activities in an unusual field, in which the son had sometimes assisted him. The nature of this pursuit, which was to have a crucial bearing on the fate of James Chambers, will shortly be clear.

Early on the morning of 24 August 1863 Chambers left home to walk the couple of miles or so to the Blind Institution. His daily walk to work would have been pleasanter than the trudge back up Carlton Road after a long and exhausting day. It was later stated that he appeared to be in good spirits, though for some reason he turned back to say goodbye to his wife after going for some distance on his journey. We do not know, however, whether any of the couple's children were present at this leave- taking. Chambers should have remained at the Institution until about seven in the evening that day, but left at four o’clock, having given the superintendent no clue that he intended to go early when they spoke to one another an hour before. Mrs Chambers had, apparently, been told by her husband that he might well not be home that night, so she was clearly not expecting him home before his usual time.

Our next sight of James Chambers is at Basford Hall, home of Alderman Thomas North, owner of the Cinder Hill Collieries. In the grounds of the Hall a Grand Fete was in progress, for the purpose of raising funds for Nottingham General Hospital. Several special trains had been laid on, and the Basford stationmaster later estimated that some 2,600 passengers were carried; the Nottingham Review, however, stated that some people thought the number to be close to 15,000. Such an attendance may be explained by the paper's observation that most of those employed in Nottingham's factories and warehouses had stayed off work for the day. The special trains terminated, not, as might have been expected, at the Midland Railway's Basford Station, but at the junction of its Nottingham-Mansfield line and the Cinder Hill Colliery branch. From here, prospective revellers were faced by what the Review considered 'a pleasant walk of ten minutes' before they reached the Hall grounds. Some of the visitors had come from as far afield as Grantham and Boston, and so great was the demand that extra- trains had to be put on at the last minute. Passengers were crammed into the parcels van and the guard's van, while 'There were not wanting adventurous youths desirous to ride on the roofs if allowed.' The roads, too, were busy with cabs and brakes bringing pleasure-seekers. The grounds of the Hall were crowded with drinking booths, a feature of the fete that was to incur the disapproval of the local press. The Nottingham Journal suggested afterwards that the publicans and refreshment vendors had done such good business that it would have been only fair for them each to have to pay a levy to fete funds.

Music and dancing were much in evidence, with the bands of the Scots Greys, the Robin Hood Rifle Volunteers, and the South Notts Yeomanry in attendance. Other musical turns, doubtless irresistible, included the Sax-Tuba Band, the Band of Hope drums and fifes, and 'Mr S. Chettle, the swinging accordeonist, with his juvenile performers'. A 'celebrated Campanologian Band' turns out to have been a group of handbell ringers, while theatrical entertainment was provided by a troupe of amateur performers from Leicester. The presentations of the last-named were deemed by the Nottingham Journal to have been too solemn, and highly unsuitable for the country fair audience present, though the Review judged that 'they went through their roles with an ease which would do credit to professionals.' Much interest was shown in a sideshow contraption called the Piping Bullfinch, a tiny automaton which, it was claimed, exactly reproduced the song of that bird, and in a magician named Professor Phillips, whose act was much hampered by a strong wind that blew his props off the stand. The weather was, in fact, to play a significant role in the day's events; although dry and fine early on, there was always a threat of rain, and the wind was often very troublesome.

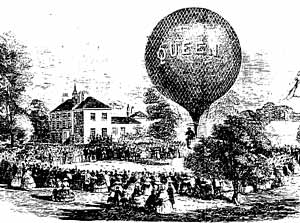

GLAISHER and COXWELL on one of their ascents, from a 19th c periodical.

GLAISHER and COXWELL on one of their ascents, from a 19th c periodical.One more attraction remains to be mentioned. This was expected to be the sensation of the entire fete, and so it was to prove, though in a way few would have foreseen. Mr Coxwell of Tottenham, the noted aeronaut, was to make an ascent in his 'new and magnificent balloon', and this thrilling event had been widely advertised throughout the Nottingham area. Henry Tracey Coxwell (1819-1900 ) was, notwithstanding the inglorious role he played in this drama, a remarkable man.

Intended for the army, he became a surgeon-dentist in London. From boyhood interested in ballooning, however, he had in 1845 founded the Aerostatic Magazine, and in his career made the astonishing number of 700 ascents, the most notable of them in 1862 when with the meteorologist James Glaisher he attained the staggering altitude of more than seven miles.

In Coxwell we see the reason for James Chambers’s presence at Basford Hall. The latter's late father Stephen Chambers had also been a well-known balloonist, known as the "Veteran Chambers', who had made numerous ascents, including one in 1853 to mark the first anniversary of the opening of Nottingham Arboretum. Chambers the younger had accompanied his father on more than twenty of his ascents from the Cremorne Gardens at Vauxhall and elsewhere. He had also taken up a balloon by himself on three or four occasions, so was by no means a complete novice.

Chambers was, of course, aware of the planned balloon ascent, and it seems certain that his presence at Basford Park was not the result of any last minute impulse. That he told his wife he might not be home that night makes it highly probable that he felt that he had a sporting chance of being involved in the ascent. Having arrived at the fete, (presumably by one of the later excursion trains), James Chambers found that Coxwell's plans were in utter disarray.

The time of the ascent had been announced as six o'clock, and Coxwell had begun the process of inflating his balloon on the afternoon of the previous day, Sunday. This job occupied nearly a full day, from 8pm on Sunday until after five on Monday, just half an hour or so before the advertised ascent time. As the newspapers were to reveal, the balloon, though no doubt magnificent, was not in fact entirely new, some parts being old: 'and those parts the upper portions, upon which the resistance of the gas would be heaviest.' As soon as gas was generated by Thomas North's workmen it was fed into the balloon, but Coxwell later asserted that it was of inferior quality, being produced from the wrong sort of coal. The whole process of inflation sounds unreliable in the extreme, the balloon having been 'placed at the mouth of an old main, laid down some years ago on the occasion of a similar fete.’ Whatever the cause of the trouble, Coxwell was quite convinced that he could not make the ascent, telling the event organisers that his balloon was insufficiently buoyant to bear a man weighing, as he did, around 11 stone 6 lbs.

At about this time the weather broke, and a sharp shower fell. 'Every bit of shelter possible was seized upon, even under the trees small knots of persons were gathered, crouching together to avoid the watery element. This incident seemed to be the harbinger of another event of a very much more disastrous character...' After some discussion, it was decided that the balloon would have to be sent up empty, with cards attached to it, asking whoever found the craft on landing to return it to Mr North by rail or other suitable conveyance. Although the absence of an aeronaut would not have given 'complete satisfaction to the sensationalists', Coxwell had sent up an unmanned balloon once before when unhappy about its capacity for supporting him. A member of the Fete Committee had indeed gone to Basford Hall to get the direction cards written when a man stepped forward from the crowd, and, introducing himself to Mr Coxwell as James Chambers, offered to take his place for the ascent.

Coxwell later stated that he did not recognize Chambers immediately, but placed him as soon as he gave his name. Although James Chambers had never been up in a balloon with him, his father had on several occasions. Coxwell told the newcomer of his problems, emphasising that the balloon would not lift him, even without any ballast. Without hesitation Chambers offered to make the ascent in Coxwell's place, pointing out that at just over nine stone he was much lighter than the advertised aeronaut. Coxwell replied that he knew Chambers to be an experienced balloonist, and that if the balloon was able to lift Chambers, with a bag of sand for ballast, he would accept his offer. He was to be adamant that he had no agreement for paying Chambers to make the ascent, and that after the latter had got in the basket or car attached to the balloon, he instructed him not to go high, and to land again within about a mile of Basford.

The weather was again deteriorating, the wind very gusty, and Coxwell had already voiced his apprehension of what might befall the balloon if its silk fabric became sodden with rain. Nonetheless, James Chambers, clearly eager to make the ascent, expressed complete confidence in the balloon and in himself, and 'slowly, very slowly, but still grandly the great air-ship rose into the sky.' Despite what Coxwell had said concerning ballast, the Nottingham Review later reported that all the sand bags had to be thrown out to get the balloon airborne, and that Chambers had only a couple of wooden beams with him to weight the car. (This last observation was. however, flatly contradicted by several other witnesses.) Before the flight had been in progress for five minutes the craft vanished into cloud, and when it emerged it was clear that something was terribly wrong. The balloon appeared partially deflated: 'like a crushed hat, pressing down on the car.' Rapidly losing height in what was now heavy rain, the balloon disappeared from sight, and the horrified spectators at Basford Park feared the worst.

Some twenty minutes later a young man arrived on horseback with the news that poor Chambers had crashed fatally to earth at Arnold. Questioned further by fete officials, the messenger related how he had seen Chambers conveyed in a cart to the Robin Hood public house in that village, and how a policeman had told him soon afterwards that he had heard from a surgeon that the balloonist was dead. All this seemed rather third-hand and less than conclusive, leaving some grounds for hope that James Chambers might in fact have survived, so two medical men present at the fete offered to go to Arnold to verify the facts. Thomas North provided a carriage, and they set off immediately. Coxwell also sent one of North's men to see if he could aid Chambers in any way.

The committee were now in a quandary; under the circumstances they did not feel that the entertainment ought to continue, but could not see how to disperse the crowds. They did. however, order the bands to stop playing, and ’ a stillness and a gloom settled upon the vast assemblage. The joyous groups of dancers were broken up. The merry parties of old people, enjoying themselves with pipe and glass, and pleasant joke or anecdote in the tents, were suddenly changed to moralists on the uncertainty of life and pity for the victim. Gradually the crowds melted away, and the grounds were empty some hours earlier than expected.'

News eventually came from Arnold that James Chambers had indeed died in the accident. The Nottingham Review reporter stated that he heard of this after leaving Basford Park, but the Journal correspondent, on the other hand, asserted that the bands continued to play until definite confirmation of the fatality was received: 'Gradually the immense crowds cleared away, and by sunset the remaining portion had bestowed themselves to the booths - to the gin and cigars. The fete was thus brought to a conclusion.'

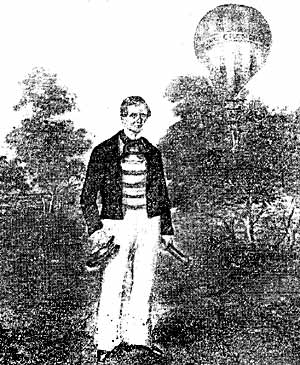

AN EARLIER BALLOON ASCENT from Basford Hall. This view is believed to date from 1859, six years before Chambers’s flight.

AN EARLIER BALLOON ASCENT from Basford Hall. This view is believed to date from 1859, six years before Chambers’s flight.The scene now shifts to the Robin Hood Inn, Church Street, Arnold, where, on the afternoon of Tuesday, 25 August, an inquest was held on the body of James Chambers, before Mr Christopher Swann, coroner for the South Division of the county. Poor Mrs Chambers had not been informed of her husband's death until that morning. At least she had not spent the night in mental agony wondering where he was, he having said he might be away for the night; the authorities, though, could not have known this, and seem to have been very tardy in finding out where the dead man’s home was.

The first witness, John Mayfield, stated that he had been in Spout Lane, Arnold (now Coppice Road), about twenty to six on the previous afternoon. He had seen the balloon moving steadily until it disappeared in cloud. When it emerged, three or four minutes later, it was descending at speed, and swaying about as if gas was escaping. The bag of the balloon then appeared to cover the car, and the balloon came to earth about 150 yards away from him, the car bouncing about two yards. By the time Mayfield and his companions got to it, there was very little gas in the balloon, though a strong smell of it hung about the spot. They found Chambers 'nearly dead', with a pocket handkerchief stuffed in his mouth, a cord wrapped round his hand, and a billycock hat on his head. Despite what the Nottingham Review was to report about Chambers's take-off from Basford Park. Mayfield stated that one sandbag remained in the car. He had heard no cry from Chambers as the balloon fell to the ground.

William Turton, one of Mayfield’s companions, told the coroner that after they had got Chambers out of the car, and rubbed his body for a while, he opened his mouth, but never stirred otherwise. The balloonist's eyes were open, and when Turton closed them they opened again.

Sergeant Blasdale of the County Police had also seen the balloon fall to earth, running to the scene in time to find other witnesses rubbing Chambers's hands, feet and chest in an attempt to revive him. He described how he had found damage to the valve of the balloon, but thought that this had been caused by the impact. His colleague Constable Hill stated that he had examined Chambers's pockets, and found, among other things, a subpoena requiring him to attend a London court as a witness.

There followed the evidence of Charles Coburn, superintendent at the Blind Institution. He had known Chambers for about a year and a half, and had regarded him as decidedly of sound mind, extremely temperate in his habits. and very conscientious in his duties. He had, however, not been given permission to leave the Institution early the previous day. Coburn considered that Chambers was not a man likely to take his own life, and pointed out that the subpoena in his pocket was not a worry to him, since he was to be paid expenses for acting as a witness in a trial. James Chambers, he said, 'Had always a predilection for aeronauting', and had assisted at the last balloon ascent from Trent Bridge.

Next to be examined was the man likely to be the most uncomfortable witness; this was Henry Coxwell, whose place Chambers had taken. He stated that he had tried the balloon three times on the fateful afternoon, at each attempt finding it incapable of bearing his weight. He had had every intention of going up himself, but had agreed to allow Chambers to replace him when the latter showed keenness to make the ascent in his stead. He was, he said, concerned at the outset of the flight when he saw Chambers throwing out ballast, contrary to his instructions, and had shouted to him to lose height, which he could have done by operating the valve. Coxwell believed that when the balloon had entered clearer air, the gas expanded very rapidly and streamed out of the safety valve, causing Chambers to inhale it; Chambers had fallen unconscious to the floor, and the cord wound round his hand (which it should not have been) had further pulled the valve open, with the result that nearly all the gas escaped. In reply to a juryman’s question Coxwell stated; 'I do not think it was proper gas. It was made more with regard to quantity than quality. Mr North's workmen had only a short time to make the gas, and it was made from a wrong description of coal. The gas was very impure, and I believe was quite unsuited for balloons.'

The foreman of the jury very reasonably asked Coxwell how, in the circumstances, he came to allow Chambers to go up, but Coxwell could offer no better reply than that he could not have expected Chambers, as a practical aeronaut, so to mismanage the valve as to allow sufficient gas to escape to render him unconscious. Coxwell was asked further searching questions by the solicitor representing Chambers's family and employers, and by a member of the Fete Committee, again replying with the limp argument that an experienced balloonist should not have found the gas dangerous, but would not have allowed himself to breathe it in. All gas, whether pure or impure, produced temporary insensibility on inhalation, said Coxwell, though the more impure, the worse the effect. He felt that Chambers had lost consciousness for long enough to lose control of the balloon.

The committee of the fete had not been consulted at all about these last-minute arrangements, so knew nothing of Chambers's sudden participation in the balloon ascent. Mr Hall, one of the fete organizers, complained to the coroner that that morning's Nottingham Daily Guardian had unjustifiably criticized his committee, and that the paper ought to be more careful of what it said. The Guardian's man present in court replied that Mr Hall had better write to his editor about this.

Mr Wright Allen, surgeon, of Arnold, told the court he was sent for at 6pm and examined James Chambers, who was by then, in his opinion, dead. His left thigh was fractured, and several ribs were broken. There was no obvious head injury, and Mr Allen did not think that Chambers had died as a result of the fall. Questioned more closely by the foreman, the doctor thought that Chambers had been rendered insensible by the gas, and that he was in an irrecoverable condition and very nearly dead by the time he reached the ground. He eventually agreed it was possible that 'the violent concussion with the earth' might have caused death.

Finally, Mr R.B. Spencer, honorary secretary to the Basford Park fete, asked leave of the coroner to speak. He repeated that the committee were quite unaware that Chambers had agreed to ascend in the balloon, and were therefore free from any blame in the matter. Spencer's attendance at the inquest was clearly a response to the critical comment in the Guardian, and he wanted that paper to print the full facts of the matter. The coroner replied that the inquest was simply to decide how James Chambers had died, and the extent of the committee’s involvement was strictly irrelevant to its proceedings. He had no doubt, however: 'That the remarks made by Mr Spencer would be taken down by the short hand writers present, and that Mr Spencer would find himself emblazoned in print.'

Summing up, Mr Swann considered that Henry Coxwell had given his evidence in an honest and straightforward manner. He was satisfied that James Chambers was himself responsible for getting into the car, that he had disregarded safety instructions given to him by Coxwell, and that Coxwell had no financial interest in sending Chambers up in the balloon. Finally, the coroner told the jury that if they came to the conclusion that the deceased man had not met his death by accident, they must discover who, if anyone, was to blame. If death was accidental, he said: 'Of course Mr Coxwell and the Committee are quite free from blame altogether.'

After half an hour, the following verdict was returned: 'That the deceased. James Chambers, ascended the balloon in a voluntary manner of his own free will: that through inhaling the gas. he became insensible, and incapable of working the balloon properly: and that the balloon coming into contact with the earth caused his death.' The death certificate issued on 29 August described Chambers as a weaver aged 37 years. Cause of death was almost word for word that given by the inquest jury, but the certificate stated that the balloon had come into 'violent collision with the earth.' Not surprisingly, all the newspapers in Nottingham published leading articles commenting on the incident; of these, the Journal and Review, weeklies of contrasting political viewpoints, may be taken as examples. Interestingly, their strictures were very similar, and underlined a feeling that the coroner, though behaving in a perfectly proper legal manner, was considered to have had let Coxwell down lightly.

The editorial in the Nottingham Journal of 28 August ended thus: 'To say the least of it, Mr Coxwell acted with far less than his usual circumspection... It is very easy to point out the fatal mistake of the poor man who cannot answer for himself; but why under all the disadvantages named above allow a volunteer to under go such peril, when there was not time to acquire satisfactory evidence of his capability to be entrusted with the sole management of the balloon? It would be but a graceful act on the part of Mr Coxwell to accompany his gift of £10 towards the bereaved family of the unfortunate Chambers, by an expression of his regret that the accident was partly due to his own want of caution. Those who are disposed to blame him the most severely, would receive such an intimation with satisfaction; as the frank acknowledgement of error is the best possible guarantee of a renewed determination, to use more effectual methods of avoiding such mistakes in future.'

This admirable standpoint was reinforced by the Nottingham Review of the same day: 'The committee, we think, should be exonerated at once from any blame - it was the aeronaut, not they, who had to prepare the balloon and arrange for the ascent; and it is the completest answer possible in reference to the substitution of poor Chambers for Mr Coxwell, to say that they simply knew nothing of it till the balloon had started on its fatal voyage. But we do not think that Mr Coxwell is himself free from all culpability. He knew that the gas was not of proper lifting quality, and, also, that no grappling irons were placed in the car; that is to say, he was aware the balloon was not neither properly prepared for ascending, nor fitted for securely descending, and yet he permitted a man to risk his life, and as it so unfortunately turned out, to lose it. We have no wish to raise a cry against Mr Cox well, and we are glad the jury did not affix to him a formal stigma by their verdict - no doubt it was only a pure mistake on his part, in the excitement of the moment, to let Chambers ascend; but it amounted, in the fatal result, to a sad error of judgment, and lack of firmness, and as such is not altogether to be passed over in silence.'

Though Coxwell had asserted that Chambers's death was the only one that had ever occurred in connection with any of his balloon exploits, he must have felt that these two Nottingham newspapers had sent him away with a sizeable flea in his ear.

Coxwell had during that week written revealingly of his role in the disaster, when replying to criticisms of him made in the London and Nottingham press. Many local people may well have regarded his immediate gift of £10 to Mrs Chambers and her five children as little more than consciencemoney; after all, had Coxwell displayed as much concern for Chambers's safety as for his own, he would have forbidden the volunteer to make the ascent.

HENRY COXWELL A portrait from the Illustrated London News on the occasion of his death in 1900.

HENRY COXWELL A portrait from the Illustrated London News on the occasion of his death in 1900.Now for Coxwell's venture into the national press. The Morning Post of 28 August must have made the bitterest reading for the aeronaut. Though acknowledging that James Chambers had disregarded Coxwell’s advice about ballast, the paper considered that the latter’s judgment had been sadly awry, and introduced a further, highly controversial note into the debate: 'After it had been clearly ascertained that an ascent was both difficult and dangerous, some of the authorities who were present recommended that it should be abandoned. But Mr Coxwell was afraid of the mob. If they were disappointed, he said, they would probably cut the balloon to pieces, and perhaps offer personal violence to himself. He spoke from past experience, and said he did not think that Nottingham people were likely to prove any exception.'

It is only fair to Coxwell to point out that neither the Nottingham Journal nor Review had suggested that public reaction to the cancellation of a manned ascent would have been anything as alarming as this, but the Morning Post continued to ride its hobby-horse: 'Be this as it may, he [Chambers] was killed. And it really does not seem to be going too far to attribute his death to the presumed ruffianism of the Nottingham public, who, having come upon the ground to witness a balloon ascent, were determined at all risks that their expectations should be gratified. If this was so it shows a brutal disregard of life... If he [Coxwell] was tempted from real apprehensions of a riot to clutch at the offer made by the man Chambers, and to start him on an errand which he dared not himself have ventured, his conduct deserves harder language than anything we have used in this article. But we trust this was not so. and that the worst that can be said of him is that use to the management of the balloon had blinded him to the danger instead of sharpening his appreciation of it.'

A reply from Coxwell appeared in The Times of the following day, addressing the Morning Post’s comments, together with the criticisms of the Fete Committee made by the Nottingham Daily Guardian. In offering a defence of his own actions, he claimed that he accepted Chambers’s offer because the latter was. crucially, some two and a half stone lighter than himself. He repeated that it had never been the case that he, Coxwell, would not make the ascent, but that he simply could not. the balloon having failed three times to get off the ground with him aboard.

Coxwell was at his least convincing, though, in advancing the following explanation: 'When I allowed the poor fellow to ascend. I might be compared to the owner of a conveyance who was prevented from running it home himself, but who permitted it to be coached by one who was not a novice, feeling sure that by enjoining him to drive slow and sure he would reach the destination.' This, one suggests from the vantage point of hindsight, was an astonishingly feeble thesis. Coxwell did, however, redeem himself somewhat by his frank closing remarks: 'I am quite willing, and indeed anxious to admit that I had better sent off my balloon alone, and borne the scoff of the dissatisfied, than risk any other life than my own... If I deserve censure let me have it; it is with me that the outcry should be raised. The Committee and the visitors I absolve from all blame. There were no roughs in Basford-park, but 25,000 orderly persons; and in conclusion, I feel bound to say that if those who feel called upon to censure felt as shocked at the occurrence as I do they would think of sympathy with the fatherless and widow, as well as of reproach, and would, after having dipped their pens in gall, dip them for the second time in their pockets, and thus join in making amends for that which cannot now be prevented.'

Amen to that, the reader will no doubt say. But is there a hint in his letter that Coxwell had indeed been apprehensive about the likely response to cancellation of the manned ascent? We shall never know. His estimate of the attendance at the fete was the highest yet; if there were indeed 25,000 present at Basford Hall on the fatal day, then the drawing power of a such a show in 1863 was considerable. And, in passing, one assumes that the stress under which he was writing led him to suggest that his critics dip their pens into their pockets, rather than their hands.

In a letter to the editor of the Nottingham Journal of 28 August, a man signing himself NO SHAM CHARITY' professed dismay at the whole purpose of the Basford Park fete. Uncannily foreshadowing views held by many today on the funding of public and social services by lotteries and private charities, he wrote: 'That the General Hospital is a noble institution no one will deny; but that it should need support from such means as the fete at Basford is a disgrace to the town and county of Nottingham.' He went on to deplore the gambling, drunkenness, and vice to be seen at the fete, and was adamant that the revelry did not cease even on the news of Chambers's death. Suggesting that such conduct was akin to Nero fiddling while Rome burned, he thundered: 'Money derived from a polluted source can never be blessed either to the giver or receiver; and it is a stain of blackest dye on our national character that Englishmen and Englishwomen refuse to support the noblest institutions of their country without receiving an equivalent in the shape of frivolous or degrading exhibitions.' He added a sombre postscript: 'Since 1 penned the above I have heard that the unhappy aeronaut was a married man, and has left a widow and five children. God help them!' The editor appended a brief comment: 'We hope He will, and that our correspondent will help them too.'

The Illustrated London News of the same day included, in addition to a brief report of James Chambers's death, a piece recalling an occasion in 1851 when one or two of its writers had made a balloon ascent from Kensington with, ironically, Stephen Chambers, the dead man's father. This had been a hair-raising affair, since the balloon burst about a mile above the ground, and fell towards the earth like a stone. His own lack of vigilance having caused the mishap in the first place, Chambers senior, 'an old man, as brave as a lion', saved all four people on board by his quick thinking, cutting loose the neck of the balloon, and so turning the craft into 'an impromptu but efficient parachute.’ The article went on to say that the journalist involved had afterwards written to The Times, calling for a ban on pleasure exhibition flights, and for the use of balloons to be restricted to scientific purposes. Others had ridiculed this proposal, suggesting that it had been put forward solely because the passengers had been half frightened out of their wits. Twelve years later, however, the Illustrated London News writer felt that he had amply made his point. A subsequent search of the 1851 press resulted in the startling discovery that not only had Stephen Chambers been in charge of the balloon on that near-catastrophic occasion, but that his son. the James Chambers we are celebrating here, was also one of the people on that ascent. It also transpired that the journalist who came within an inch of losing his life was the celebrated writer George Augustus Sala, then in his early twenties, and at the time better known as an illustrator.

What happened was this. The balloon had ascended on the evening of 8 September 1851 from Kensington, and, as was said to be customary at the time, Chambers senior had tied a silk handkerchief around the neck of the bag. His attention was occupied in waving flags and releasing 'some comical figures of paper' for the amusement of onlookers on the ground, and he consequently failed to observe that the balloon was gaining height very quickly. The air pressure lessened as they reached thinner air, and the gas inside the bag accordingly expanded rapidly; with the neck of the balloon tied, there was no way for the gas to escape. Sala then 'heard a report like that of a musket' above his head, and it was evident that the bag had burst. Throughout, the elder Chambers was calm and collected, and acted with great presence of mind. As well as cutting the neck of the bag away to achieve his parachute effect, he made the passengers throw overboard everything that was weighing it down: grappling irons, sandbags, greatcoats, bags, all went. The rate of descent, though still rapid, was checked, and the balloon landed in a market-gardener's field at Fulham, its occupants all in a heap, but quite unhurt except for a grazed elbow suffered by Sala.

On 11 September 1851 a letter from the youthful George Augustus Sala appeared in The Times. Very shaken after his experience, he wrote: 'The cause I think lies in a nutshell, and I am loth to allude to it. since it argues a lack of prudence on the part of the person who, by his presence of mind, saved our lives subsequently...' As the 1863 article in the Illustrated London News recalled, he went on to condemn the frivolous use of balloons: 'It is madness and folly to permit any enthusiast or any charlatan who may be the possessor of a silk bag which he can afford to fill with coal gas to risk his own life among the clouds, as well as those of the madcaps who are with him. for the amusement of gobe- mouches [flycatchers] who have paid a shilling a-head to see their fellow creatures commit constructive suicide.' All this was strong stuff, but one trusts that Sala would have categorized Chambers senior as an enthusiast, which he surely was, rather than as a charlatan.

It is sobering to reflect that, some twelve years before he lost his life on the flight between Basford and Arnold, while entertaining a pleasure-seeking crowd of the sort execrated by Sala, the young James Chambers had come so close to death in another balloon accident.

His funeral took place on Sunday, 30 August 1863, his body being conveyed from his home (given as Thorneywood Lane in the burial certificate) in a hearse followed by three mourning coaches, 'and accompanied by a very numerous body of people.' At Sneinton Market the cortege was met by the Temperance band of the Band of Hope, whose musicians took up position in front of the hearse, and played Handel's Dead March in Saul as the procession wound its way to Nottingham General Cemetery, arriving about half past two. According to the Review, ’Much sympathy was manifested for the widow and children of the deceased.' The funeral service was read in the Dissenters' chapel in the cemetery by William Frisby, resident chaplain there; he reminded the mourners of 'the uncertainty of life and the importance of being prepared for death.' Among those who followed the body of James Chambers to the graveside were Charles Coburn, superintendent at the Blind Institution, and a number of Chambers's pupils from his weaving and mat-making classes. The Nottingham Journal had to report one highly offensive aspect of the proceedings: 'There was a large crowd of people in the Cemetery, the greater part of whom showed an utter absence of that decorum which the scene ought to have enforced upon them. It is but just to say, however, that the more gross part of the improprieties, such as whistling, shouting, and jostling against one another, were committed by young persons.' This incident provides an interesting sidelight on the Victorian values so nostagically espoused by some in recent years.

One member of the Chambers family who had found it hard to attend the funeral was the dead man’s widowed mother. It was reported that Westminster Police Court had received a letter from her, asking that she might be given enough money from the poor-box to enable her to travel to Nottingham for the ceremony. One of the court officers stated that she was 'in poor circumstances. and a very deserving woman,' and the court accordingly ordered that she be allowed the train fare, with 7/6d for added expenses, and that the officer see her off at King's Cross. (In case this seems an unlikely point of departure for Nottingham, it should be mentioned that the opening of St Pancras Station was still several years away in the future.)

We have heard already of Thomas Coxwell’s prompt offer of £10 to Mrs Chambers; there were also immediate plans in Nottingham to raise money for her and the children. On 4 September the Journal reported that a total of £11 had already been received from several well-wishers, some of them members of the Town Council. The largest donation was £5 from Thomas North, owner of Basford Hall. Although £11 may sound little enough, it was probably sufficient for a year's rent on a working-class house in the town.

Mr Coburn of the Blind Institution had also written to the papers asking for contributions, and a fund-raising effort of a different kind was a benefit concert at the Mechanics' Hall, on 8 September. The Robin Hood Rifles Band played, accompanying several local vocalists and chorus. There was, according to the local press, a large attendance at the concert, which included the overture to Herold's 'Zampa', and several vocal and instrumental solos. It was reported that: 'The flute solo by Mr Webster... showed this gentleman to be a most accomplished master of his instrument.' We can be pretty certain that this musician was John Webster, lace dresser of Sneinton, whose factory was in Dakeyne Street, and who lived in Belvoir Terrace. Remembered nearly seventy years later as the uncrowned king of Sneinton, this mainstay of the community had formed No. 9 (Clumber) Company of the Robin Hoods, and acted as its first captain. He also played the flute in the Sneinton church band, where he was a churchwarden. Not only did all the performers give their services free. but the Nottingham newspapers carried complimentary advertisements for the concert, and a local printer, Allen of Long Row, printed the programmes at his own expense. After the hire of the room had been paid, a further £25.17.6d was placed to Mrs Chambers's credit at the Nottingham bank of Moore & Robinson, Beastmarket Hill.

One well-meaning offer of assistance was, however, turned down, as explained in the Nottingham Review of 4 September. 'Mr Jackson, the Midland Aeronaut of Derby, has generously offered to make an ascent with his balloon at Nottingham, at his own cost, for the benefit of the widow and orphans of the unfortunate Chambers. But while duly appreciating his motives, his liberal offer has been declined as too 'sensational' an exhibition under the late distressing circumstances.'

On the evening before the concert performance, a meeting had been held at the People's Hall in Beck Lane (now Heathcote Street), to decide how best to collect subscriptions from members of the public who wanted to give something for the Chambers family. This, unhappily, was poorly attended, nor were its organizers aware of how much Charles Coburn's appeal had raised, or of the way he was collecting donations. One helpful contribution to the proceedings came from a Mr Manfull of Lenton. (This was probably John Manfull, druggist of Willoughby Street. Was he an ancestor of Claude Manfull, whose chemist’s shop at the corner of Trent Road and Thurgarton Street was long a feature of Sneinton?) He had a few years earlier devised a scheme for bringing in small donations for a man who had been stabbed while crossing The Park. This took the form of a card with 240 squares on it, in each of which a donor could put his or her name, and the amount given. Even if every square represented a gift of just a penny, a completed card would represent £1 for Mrs Chambers. (There were, of couse, 240 pence to the pound then.) Manfull suggested that if a hundred of these cards were printed, and handed to as many boys, they would quickly get results, no one being likely to refuse a sum as small as a penny. He also advocated the displaying of the cards in hotels and warehouses, and was sure that a considerable amount of cash could speedily be raised. The meeting agreed with him, and general disappointment was voiced over the lukewarm response so far in the town to plans for helping the widow, especially as one man present reported that 'the poor woman was in the greatest distress.' It was decided to adjourn the meeting for a week, while Manfull communicated with Mr Coburn.

The turn-out at the People’s Hall was again sparse when the meeting resumed on 14 September. A local physician, Dr Cavania of Station Street, stated that he had had some circulars printed giving details of the matter, and requesting subscriptions. His daughter had posted a number of these to the nobility and gentry of the neighbourhood, including Lord Scarsdale of Kedleston Hall, and the doctor was confident of raising a substantial amount for the Chambers family. Cavania also suggested that about a hundred gentlemen in Nottingham should each take a card, and make a personal collection among the residents of his own street. The meeting evidently did not think much of this idea, preferring Manfull's scheme. and a committee was formed to organize this. Dr Cavania thereupon offered to have a hundred subscription cards printed at his expense for the use of the committee.

And what next? Sadly, not very much, as far as one can discover. A search of Nottingham newspapers published over the following weeks uncovered no reference to the Chambers family, though it is possible that afterwards there may have been some announcement of the final result of the appeal. Other stories clamoured for the attention of the press, and it seems that the balloon disaster and the plight of the dead man's dependents soon passed from public attention.

On 23 October the Review carried a brief notice to the effect that, after the expenses of holding the Basford fete had been paid, a surplus of £163 had been sent to the General Hospital funds. There was no mention of James Chambers. If Coxwell was correct, and 25,000 people had attended, this represented a profit of about 1½d (0.65p) per visitor. A week later the papers noted the annual meeting of the governors of the Blind Institution; it was reported that at the meeting thanks were given to, among others, subscribers, committee members, and the ladies of the Visiting Committee. No reference was made to the death of Chambers, or to any of the teaching staff of the Institution.

As already indicated, the Chambers family had left the neighbourhood of Carlton Road and Thorneywood Lane by the time the 1871 census was carried out. A lengthy trawl through the returns for the remainder of Nottingham, however, brought them to light at 72 Arkwright Street, in the Meadows. Almost eight years after her husband's death, his widow Rachel Ann Chambers, aged 40, was listed at this address as a hair net threader. Like her three eldest children, she had been born in Middlesex. Elizabeth, aged 16, was a dressmaker's apprentice, and Margaret (15) a hosiery machine stitcher. Stephen J., the only son, was twelve, and still at school, as were his younger sisters Emma and Annie. Stephen, four when his father died, could have had only the haziest recollection of James Chambers, and Emma, only two at the time, possibly not even that. Annie, a baby under a year old in 1863, would have been unable to remember him at all.

JAMES CHAMBERS'S FATHER, STEPHEN: A painting depicting him with his balloon, from which a trapeze artiste hangs. From the Nottinghamshire Guardian 1925.

JAMES CHAMBERS'S FATHER, STEPHEN: A painting depicting him with his balloon, from which a trapeze artiste hangs. From the Nottinghamshire Guardian 1925.Over sixty years later, though, on 21 November 1925, a short article written by S.J. Chambers, (then aged 66 or 67) appeared in the Nottinghamshire Guardian. In it he related how his father James had made the ascent from Basford Park in place of Mr Coxwell, and perished in the attempt. Much of the tale had evidently been passed down to Mr Chambers by word of mouth, and understandably he got some of the details wrong. James Chambers did not go to Basford in the morning, for instance, and was not prevailed upon by anyone else to make the ascent. Nor did he die of a broken neck, as his son stated. It was nonetheless a moving little account, and proof that the Sneinton balloonist was still remembered, even if only by his own family. S.J. Chambers went on to refer to the ascent made by his grandfather and father in 1851, when disaster had narrowly been averted. He stated that George Augustus Sala had later published a garbled version of these events in the August 1892 issue of The Million, including, some forty years after the accident, some highly-coloured extra details. An illustration accompanying Mr Chambers’s Guardian article did, however, lend weight to Sala's contention that many early balloon ascents had been harebrained and sensational ones. This was a treasured family painting, showing Stephen Chambers posed in front of his balloon, from which hung a trapeze with an acrobat on it.

S.J. Chambers also told Guardian readers that his grandfather had been given a gold watch, and his wife a silk dress, after his 1853 balloon ascent from Nottingham Arboretum. He had also received £50, and made some extra money by charging the public a shilling a go to ascend in his balloon, which at the time was tethered to the ground by a long rope. From all we have heard about them, Stephen and James Chambers, father and son aeronauts, were clearly a remarkable and dauntless pair.

The casual stroller through Nottingham General Cemetery (a walk highly recommended) may still come upon a modest slate headstone, a few yards to the right of the main path not far in from the Waverley Street entrance. It reads as follows:

IN

AFFECTIONATE REMEMBRANCE OF

JAMES CHAMBERS,

WHO ASCENDED IN A BALLOON

FROM BASFORD PARK AND

LOST HIS LIFE IN CONSEQUENCE

OF ITS RAPID DESCENT

AUGUST 24th 1863, AGED 35 YEARS.

What though awhile in dust I slumber here

And leave behind a wife and children dear

He who redeems will not their grief despise

But guide them by his mercy to the skies

ALSO RACHEL ANN,

WIFE OF THE ABOVE

WHO DIED JANUARY 16th 1900

AGED 69 YEARS

The toil, the pain, the grief are past.

And she is safely home.

Little remains to be added, it is self- evident that Mrs Chambers was able to provide a headstone for her husband, no negligible outlay for a needy person; perhaps the fund-raisers organized this for her. The monumental mason inscribed James Chambers's age as 35, rather than the 37 stated on the death certificate; doubtless this was done at his widow's direction. In remembering a man who was surely the only Sneinton resident ever to die in a balloon accident, it is right to spare a thought for Mrs Rachel Chambers. For a poor woman in Victorian England, thirty-six years of widowhood would have been unlikely to hold out the prospect of an easy life.

< Previous