< Previous

SUCH STRANGE CHURCHYARDS:

An old burial ground .... and the artist who painted it

By Stephen Best

'Such strange churchyards hide in the City of London; churchyards sometimes so entirely detached from churches, always so pressed upon by houses; so small, so rank, so silent, so forgotten, except by the few people who ever look down into them from their smoky windows.'

(Charles Dickens: The Uncommercial Traveller)

THIS SCENE ON THE EDGE of Sneinton has changed out of all recognition since it was painted three-quarters of a century ago, and work just begun on the new Ice Arena development will again transform the area in the very near future.

Annie Laurie Gilbert's watercolour of the Dean Street entrance to Carter Gate Recreation Ground is dated February 1920. This playground had been made from part of one of the three burying grounds in, or just off, Barker Gate; all of these were opened in the eighteenth or nineteenth centuries to supplement the overcrowded St Mary's churchyard in High Pavement. A hundred years ago they were familiarly and conveniently known as Top, Middle and Bottom Grounds, reflecting their respective positions on the slope of Barker Gate. Former residents of the neighbourhood, who as children played in the old burial grounds between the wars, still remember them as Top Bury, Middle Bury, and the one in our picture, Bottom Bury.

The earliest of the three, Middle Ground, was granted to the parish in 1742 for ten shillings by the Duke of Kingston. At that time it was an area of gardens, with a row of buildings along the Bellar Gate frontage. The site, now a rest garden at the corner of Bellar Gate and Barker Gate, is well known to passers by, and at the time of writing (June 1997) a familiar landmark along the bus route from Sneinton into the city centre. It is notable for the display of spring bulbs which beautifies the corner each year, while a few gravestones remain to remind the onlooker that this was once a burial ground. The condition of these reflects little credit on the authorities; a couple of broken stones lie by the pavement, while several neglected slate headstones, two of them illegible, are propped up behind shrubs. Four slate stones, in a better state of preservation, lean against the old St Mary's School building a few yards away; these, however, are on private property, inaccessible to the interested enquirer, and extremely difficult to make out from the gate. Perhaps the best of them commemorates Richard Goodall, who died in 1804. Ideally, all the gravestones remaining from the Middle Ground should be set up in the public rest garden, in a place where they could be read by everyone.

Between this old plot and the erstwhile school stands the attractive arched entrance gate to the latter, with a carved inscription above it. The rather similar gateway in the illustration shown here has led some people to assume, wrongly if understandably, that the scene in the painting is the corner of Barker Gate and Bellar Gate.

Top Ground, the second of the St Mary's burial grounds in this area, lies between Barker Gate and Woolpack Lane, and is today a pleasantly secluded rest garden. Snugly screened from Barker Gate by high buildings, it was opened in 1786, and the earliest of the thirty or so surviving headstones arranged along the walls are from that same decade. It is worth spending a few minutes in reading the inscriptions here; most of them, being carved on slate, are still quite easy to make out. They include memorials to Quarter-Master John Hoare of the 7th, or Queen's Own, Light Dragoons, 1795: William Hickling, who died in 1808, aged twelve: and John Smith, 'a native of Leicester, who died of a malignant fever' in 1809. The most appealing lines of all. however, are to the memory of Samuel Wood, 'born at Crich. in Derbyshire', who died in 1787; hidden away in a corner behind a vigorous flowering shrub is the gravestone of this 'plain, inoffensive, honest Man.'

These two earlier burying grounds becoming filled up, a third site was purchased in 1813, at the cost of 7/6d a yard, in a field belonging to George de Ligne Gregory, after whom the nearby George Street was named. That street was formerly known as Gregory's Paddock, the family's mansion having stood at its southern end, on the site now occupied by Sonny’s Restaurant and the former Lloyds Bank, now Lloyds No. 1 Cafe Bar.

Situated between Bellar Gate on the west and Carter Gate on the east, the new burial ground was bounded on the north side by properties abutting on to Barker Gate. From the start pretty well surrounded on most sides by houses, it possessed three entrances: from Dean Street, Carter Gate, and Olive Yard (off Barker Gate). The first and most important of these is the subject of A.L. Gilbert’s painting. Over the years the place became known by a confusing variety of names; Carter Gate Burial Ground: St Mary's Burying Ground no. 3: and Bottom Ground. Further to complicate matters, it was also frequently referred to simply as one of the Barker Gate Burial Grounds.

Following its consecration in 1817 by the Archbishop of York, Edward Harcourt, the early years of Bottom Ground were marked by a couple of grim episodes. The first, sensational, occurrence was in 1827, when it was discovered that body-snatching had been taking place at Barker Gate. A bookkeeper employed at Pickford's warehouse at the Leen Bridge (just about where the city end of London Road is now) became suspicious of a man calling himself Smith, who brought in a hamper to be conveyed to London. On being told either to open the hamper or take it away, Smith made off, and, after a brief struggle, he and his confederate escaped from a Pickford's porter who had gone in pursuit. The hamper proved to contain the bodies of an old woman and a little boy, the former buried only the previous day. When this became known, panic and fury broke out among those families who had recently had relations interred at the three burial grounds: it was reported that over thirty- graves were found to have been opened and the bodies taken away, presumably to be sold for dissection. No one was ever brought to book for these crimes, though William Davis, or ’Old Friday’, the St Mary's parish gravedigger, was popularly believed to have been implicated in the grisly business. Nothing was proved against him, but he was nonetheless physically attacked in both Nottingham and Arnold.

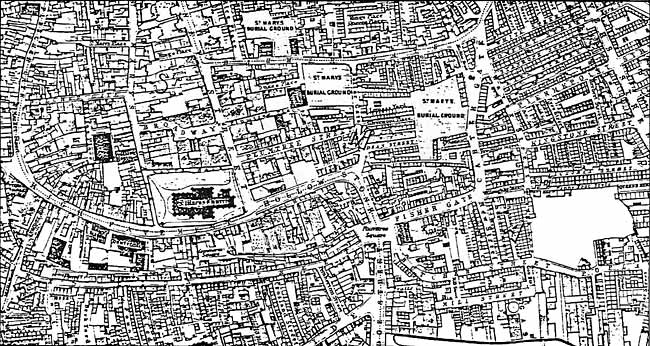

Barker Gate and neighbouring streets, showing the three St Mary's Burial Grounds mentioned in the text. From Salmon’s map of Nottingham, 1861.

Five years after this, Nottingham suffered a severe cholera epidemic, some 300 townspeople (sources disagree about the exact number) dying of the disease. Samuel Fox, Quaker owner of a grocery shop in High Street, promptly gave land for a new cholera burial ground in open country at the north-east end of Beck Street; this is now the rest garden at the corner of St Ann's Well Road and Bath Street. Though records are imprecise, it is clear that until the new cemetery came into use most of the cholera victims were buried in the Carter Gate Ground, which was still quite new and therefore had the greatest number of available plots. Tales were passed down from generation to generation of uncoffined bodies heaped in common graves, and there were even rumours of people having been buried alive, so quickly were they buried once death from cholera had been confirmed. Alfred Stapleton, in his 'Nottingham Graveyard Guide', published in 1911, recorded that Bottom Ground then contained the gravestone of George Wilcock. who had died on 1 September 1832. The 'Nottingham Date Book' relates how Wilcock, a framesmith, went to visit a sick friend, but turned back on learning that the man was ill with cholera. He returned home in a state of alarm and was immediately- seized with the same disease, both men dying of it within a few hours of each other.

In 1856 Carter Gate was one of the burying grounds in the densely built up and overpopulated centre of Nottingham in which further interments were forbidden, except in family vaults and walled graves. The Nottingham Enclosure Act of 1845 had already laid it down that no house could be erected, or used as a dwelling, within sixty feet of the boundary of a cemetery. It must, therefore, have been a relief to the Medical Officer of Health when he was able to state in his annual report for 1856 that there was now provision in the town for all burials to be well away from dwelling houses. There was ample space in the cemetery given by Samuel Fox, while the General Cemetery at Canning Circus, opened in 1838, had been newly extended, and the Church Cemetery in Forest Road had just come into use.

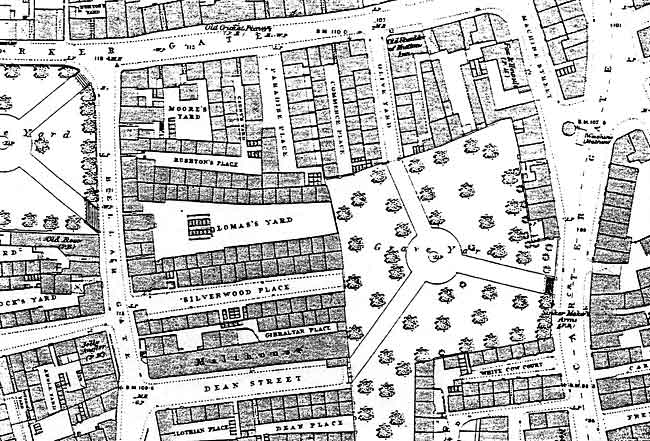

Bottom Ground, Carter Gate, as shown on an Ordnance Survey map of the 1880s. Coronation Buildings occupies the site of the building in Dean Street marked 'Malthouse', and the Ice Stadium was built immediately to the north of it.

Bottom Ground, Carter Gate, as shown on an Ordnance Survey map of the 1880s. Coronation Buildings occupies the site of the building in Dean Street marked 'Malthouse', and the Ice Stadium was built immediately to the north of it.Closed completely in 1887, Bottom Ground was, like the other Barker Gate burial grounds, partly asphalted sometime before the turn of the century to serve as a recreation ground. In the first decade of this century, Stapleton reported that a number of the horizontal gravestones had become lost through the encroachment of grass, and some inscriptions worn away by the feet of pedestrians. He was, nonetheless, able to copy some 239 inscriptions from memorials in the Barker Gate grounds. The subsequent loss of nearly all of these leaves an irreparable gap in our local history knowledge. By 1902 all three grounds were in the care of the Kyrle Society, a philanthropic organisation that sought to improve the lot of working people by laying out parks, encouraging house decoration, and gardening. The remaining burying ground portion at Carter Gate, grassed and thickly planted with trees, was demarcated by what were described as weak wrought iron railings.

The gateway in the picture led from the site to the end of Dean Street, a rather short cul-de-sac off Bellar Gate. People still lived in Dean Street when Annie Laurie Gilbert painted the spot, and one of the back-to-back houses depicted here is brightened up by a bedroom window box. At a time when the term is frequently misapplied to other kinds of terrace housing, it is important to remember just how back-to-back dwellings were laid out. The row of houses visible through the gateway comprised two lots of dwellings: the portion on the near side of the roof ridge belonged to houses in Dean Street, while the left-hand side formed houses built back-to-back with these, their doors opening on to Dean Place. Each dwelling possessed only one outside wall, with the exception of the end houses, which each had an external, though blank, side wall. Further to the left in the painting can be seen the roofs of houses in White Cow Yard.

The entrance gate to Carter Gate Burial Ground from Dean Street. A photograph of about 1920.

The entrance gate to Carter Gate Burial Ground from Dean Street. A photograph of about 1920.A photograph of the gateway was taken from Dean Street at just about the time the watercolour was done. Standing as it did at the end of the little street, and dominating the small houses, the arch possessed a distinctly monumental quality, as befitted the former carriage entrance to the burial ground. Its side walls were embellished with handsome volutes, and the Dean Street face of the pediment bore the date of building in Roman numerals. It is interesting that the photograph shows the window box recorded by Annie Laurie Gilbert.

In April 1939 the Ice Stadium was opened, the old burying ground disappearing beneath its car park. Designed by Reginald Cooper of Russell House, Talbot Street, it was built to accommodate 1,500 people on an ice floor measuring 210 by ninety feet. Its construction effectively blotted out nearly all that can be seen in the watercolour. The only point of reference surviving in 1997 is the little turret with a conical roof, distinguishing feature of a warehouse in Trivett Square in the Lace Market, near the end of Short Hill and the top of Short Stairs. It remains to be seen how this building survives the current redevelopment of the Malin Hill and Short Stairs area. It is an important accent in the skyline, however, and too valuable to be lost. The ugly, and now apparently disused, post-war warehouse in Dean Street built on the site of the old houses for J.R. Nason, wholesale produce merchants, interrupts the view of the turret from the Ice Stadium car park, and makes it impossible to sight it from exactly the same spot as the painter did seventy-seven years ago. For the time being, however, one can stand near the Lower Parliament Street boundary wall of the car park, and, using the present pedestrian entrance to Dean Street as a guide, just see the tip of the turret and so work out roughly where the artist sat to record this view. An excellent prospect of the Trivett Square skyline can be had from Fisher Gate or Bellar Gate, and from the corner of London Road and Canal Street.

Dean Street has lacked charm for some years now. Apart from the uncompromising backside of the Ice Stadium, and the Nason warehouse just mentioned, (by the Nottingham architects Bromley and Cartwright,) it contains only one building. This, however, provides such character as the street still possesses; bearing the name 'Coronation Buildings', and dated 1911, it features windows of a style unlike anything one can remember seeing elsewhere in Nottingham. Built in the aforementioned year to the design of Parkin and Newbold of Victoria Street for George Samuel Berridge, of Wells and Berridge, fancy box makers of Plumptre Street, it served for many years as the premises of successive firms of box makers. It is currently occupied by Reelex lace manufacturers. Just out of sight in Annie Laurie Gilbert's painting, this building stands across the street from where the row of houses used to be.

The Nottingham Guardian Journal of 3 August 1957 reported that a number of bodies at Bottom Ground were to be re- interred at Wilford Hill Cemetery because public lavatories were planned for part of the car park site; these were duly built, and at the time of writing remain in Lower Parliament Street (formerly Carter Gate), though no longer in use. Many human remains, however, still lie beneath the car park, a 1997 newspaper story suggesting that hundreds of bodies would require reburial once work began on the new Ice Stadium. It is likely, though, that the number will run into thousands rather than hundreds. In sad contrast to the other two Barker Gate burying grounds, the Bottom Ground has no surviving gravestones; the present writer, however, can remember a time when a few stones were dotted around the margins of the site.

Twenty years before the lavatories were put up here, the Stadium Hotel had been a very short-lived feature of the car park frontage. Opened, like the Ice Stadium, just before the outbreak of war, it was destroyed through enemy action in Nottingham's worst air raid, during the night of 8/9 May 1941. Also bombed in that same raid was the millinery department at Pullman's store just across the road in Lower Parliament Street. When Pullman's closed down many years after the war, the depressingly humdrum block containing the Sun Valley amusement arcade was built in its place.

Now for a brief account of the artist. Annie Laurie Gilbert was a prolific and skilled painter in watercolour, who worked over a remarkably long period. Known examples of her work are dated as early as 1874 and as late as 1935. Born in November 1851, she came from a richly and diversely talented family. Her father was the Hull- born Nottingham architect Isaac Charles Gilbert, in whose Clinton Street offices the young Fothergill Watson began a professional career that led to his becoming Nottingham's most immediately recognizable architect. Annie's mother Anne (nee Gee) was the author of 'Botany for Beginners', and 'Recollections of Old Nottingham' ; the latter, published in 1904, is a valuable and frequently quoted source of first-hand information on the town in the nineteenth century. Mrs Gilbert also established a private school at the family home, 6 Arthur Street, off Waverley Street, to which the Gilberts had moved from Clinton Street when Annie Laurie was a girl. She began by teaching only the children of a few family friends, but her school flourished and for some years enjoyed a good reputation in Nottingham.

Annie Laurie Gilbert's paternal grandmother was Anne Taylor, one of the celebrated Taylor sisters of Ongar. These were Anne and Jane, who wrote numerous children's rhymes and hymns, many of them collected in a volume titled 'Original Poems for Infant Minds'. Jane Taylor was the author of the familiar 'Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star', while several of Anne's hymns became popular, as did verses by her with titles like 'My Mother', 'Meddlesome Mattie', and the 'Notorious Glutton'.

Anne Taylor was wooed in remarkable fashion by the Rev. Joseph Gilbert, her future husband. He had never met her, but having read her works and heard of her through her friends, wrote asking if he might meet her with a view to marriage. Armed with letters of recommendation from Anne's parents, he travelled from Essex to North Devon to see her, in winter, on the outside of a coach, and a happy marriage of thirty nine years ensued. Joseph Gilbert was later for twenty six years pastor of Friar Lane Independent Chapel in Nottingham, and a noted lecturer and preacher.

Isaac Charles Gilbert's brother, Annie Laurie's Uncle Josiah, was well-known as an artist, writer, and foreign traveller, whose published books included 'Cadore, or Titian's Country' : 'Dolomite Mountains' : 'Art, its Scope and Purpose' : and 'Landscape in Art before Claude and Salvator.' He drew or painted many leading Nottingham citizens of his day, and his portrait of Alfred Lowe is reproduced in Sneinton Magazine no. 62. Another uncle, Sir Henry Gilbert, was responsible for important advances in agricultural chemistry in the 19th century; especially noted for his work on nitrogen fertilizers, he became professor of rural economy at Oxford.

While still a young woman, Annie Laurie Gilbert worked, as did two of her sisters, as an assistant in her mother's private school at Arthur Street. Clearly inheriting her father's feeling for buildings, she preferred to paint landscapes or topographical scenes, and rarely included people in her watercolours. Indeed, one senses that she did not greatly enjoy painting the human figure. In addition to the considerable pleasure given by her paintings, her work, like that of her better-known Nottingham contemporary T.W. Hammond, exists in public and private collections as a most valuable record of vanished Nottingham scenes, some of which would otherwise now be lost without trace. (Hammond, incidentally, did a drawing of Carter Gate, in which the railings and boundary wall of Bottom Ground feature prominently.)

Unlike some Victorian and Edwardian women artists in comfortable circumstances, A.L. Gilbert did not restrict herself to conventionally pretty locations, but sought out other places that interested her, however grimy and unfashionable they may have been. In and around Sneinton, for instance, she painted in 1919 Green's Mill, then in a derelict state without sails, and with picturesquely decayed cap and fantail. At least two different studies of the mill by her are known, and have been reproduced several times.

Before the Great War she had executed other watercolours of various parts of the neighbourhood. These include one of Leen Side, with the Lace Market and St Mary’s church beyond; and a couple of contrasting views of the canal on either side of London Road. One of the latter shows the Great Northern Railway viaduct looming above the towpath, while the other, reproduced on the cover of Sneinton Magazine no. 31, provides a detailed picture of the Island Street warehouses fronting the waterway, and of the craft at work on it. This last location has, as the reader will doubtless know, lately been thoroughly and insensitively removed from the Nottingham townscape, and nearly every trace of its industrial history unnecessarily obliterated. One cannot help feeling that it should have been possible to redevelop the Island Street site in a way that would have satisfied modern commercial needs, while at the same time allowing more reminders of its significant past to survive.

Annie Laurie Gilbert died on 29 November 1943 at 4 Newstead Grove, just across the Arboretum from the Arthur Street house in which she lived for many years. She had recently passed her 92nd birthday, and was described on her death certificate as a 'Spinster of independent means.' Her will revealed that she left effects amounting to £6067; at a time when the average weekly wage was less than £5, this represented a fairly substantial sum. She was buried with her parents in the family grave in Nottingham General Cemetery, not far from the wall separating it from the Friends' Meeting House. A few yards away from her burial place stands the tall memorial of her uncle Josiah Gilbert, who is described in its inscription as 'Artist, traveller, and man of letters.' A third Gilbert monument in the General Cemetery commemorates the Rev. Joseph Gilbert and his wife Anne (nee Taylor); this can be found at the side of the top path near the Canning Circus entrance to the cemetery.

It may be mentioned in passing that the original Annie Laurie (1682-1761) was the youngest daughter of Sir Robert Laurie of Maxwelton, Dumfriesshire, and that the poem bearing her name was written by William Douglas, an unsuccessful suitor of hers. The famous musical setting was, however, composed in the mid-1830s by Alicia Ann Spottiswoode, later Lady John Scott, who added an extra verse. Published only a year or two before Annie Laurie Gilbert’s birth, it had, we may assume, become a particular favourite of her parents. A few years afterwards the song enjoyed immense popularity amongst the British troops fighting in the Crimea.

There are still residents of Sneinton, now in their late eighties, who would have been about ten or eleven when Annie Laurie Gilbert came to paint the windmill. One or two of them may even have seen her at work on Belvoir Hill. It is an appealing thought.

POSTSCRIPT

At the beginning of this short account appears a quotation from Charles Dickens, and another may appropriately end it. One day this year I returned home from visiting the three Barker Gate burial grounds, having sadly noticed men in all of them sitting on the seats, on old crates, or lying on the the ground: drinking, eating, or just gazing into space. It was then I remembered that Dickens had mentioned old London graveyards somewhere in 'The Uncommercial Traveller’. Looking up the relevant essay, 'The City of the Absent', I found the following, written in 1863:

'Blinking old men who are let out of workhouses by the hour, have a tendency to sit on bits of coping stone in these churchyards, leaning with both hands on their sticks and asthmatically gasping. The more depressed class of beggars too. bring hither broken meats, and munch.'

Victorian values?

As always, I am glad to acknowledge the facilities afforded by Nottinghamshire Local Studies Library and Nottinghamshire Archives Office. I am also grateful to Alfred Stapleton for his far-sighted survey of Nottingham's graveyards early this century, and especially indebted to Annie Laurie Gilbert for painting one of them.

STOP PRESS

Before this article goes to the printers, it can be reported that the Nason warehouse in Dean Street has just been demolished. For the moment, therefore, an onlooker in the Ice Stadium car park is able to see rather more of the Trivett Square building in the background of Annie Laurie Gilbert's painting. Other changes to this scene may occur at any time.

A 1997 photograph of the location painted by Annie Laurie Gilbert in 1920. The turret on the Trivett Square warehouse is the only feature to have survived the intervening years and the change from recreation ground to car park.

A 1997 photograph of the location painted by Annie Laurie Gilbert in 1920. The turret on the Trivett Square warehouse is the only feature to have survived the intervening years and the change from recreation ground to car park.

< Previous