< Previous

ABOUT CHAPS:

Sneinton connections in 'Contemporary Biographies'

By Stephen Best

'Geography is about maps,

But Biography is about chaps'

(E.C.Bentley: Biography for Beginners)

A MINE OF INFORMATION on notable local people at the turn of the century is to be found in a large and handsome volume published in 1901. Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire at the Opening of the Twentieth Century - Contemporary Biographies, by J. Potter Briscoe and W.T. Pike, has been mentioned several times in historical articles in earlier Sneinton Magazines, but richly repays a closer look.

John Potter Briscoe, Nottingham’s chief librarian between 1868 and 1916, was responsible for the book's essays describing the history and current state of the two counties. These are necessarily brief and rather superficial, but include very useful photographs of country mansions and other private houses in Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire not illustrated elsewhere. The short biographies were edited by W.T. Pike of Brighton, who was also publisher of the book. The selection of personalities is curiously haphazard, but again the photographs are of enormous value, being portraits of many whose faces would otherwise be unknown to us.

The Nottinghamshire half of the volume includes about 350 men - no women, be it noted, only men. This is the aspect of the book most likely to raise eyebrows nowadays, and the absence of women undoubtedly makes for a wholly unbalanced picture of the county at the time. However, as I wrote elsewhere in an account of gravestone inscriptions in Nottingham's nineteenth-century cemeteries, it is not the present-day researcher's fault that monumental inscriptions and biographical reference books such as this treated women merely as adjuncts of men. One can only deplore this failing, and do one's best with the data given. While regretting that those described in it are exclusively male, and recognizing its other, less obvious, failings, it must be repeated that Contemporary Biographies still contains much to interest us today.

The ranks of great and good men presented here display some curious omissions, and it is hard to escape the conclusion that those included compiled their own entries, perhaps filling in a form provided by the publishers. It also seems likely that, apart from a favoured few, they paid a fee to secure inclusion. Such exceptions possibly occur in the first few men shown: the Lord Lieutenant, Bishop of Southwell and his assistant bishop, Members of Parliament, the Mayor of Nottingham and High Sheriff of Nottinghamshire. Would anyone have had the nerve to ask them for payment? These dignitaries are also accorded larger portraits than the others, who are classified under the following headings - Nobility and Gentry: Military and Volunteers: Clergy: Medical: Dental: Legal: Music: Literary and Scholastic: Architects and Surveyors: Accountants: Commercial: Stockbrokers, Auctioneers and Insurance: Civil and Mining Engineers: Veterinary Surgeons: and Sport.

Whether most of those portrayed in the book felt that inclusion would be socially or financially useful to them, or whether simple vanity dictated their presence, we do not know. What is noticeable, as already suggested, is that in several categories some prominent and influential men were left out, or chose to leave themselves out. There are, for example, no entries among the Nobility and Gentry for Lord Savile of Rufford Abbey or the Edges of Strelley Hall. The rectors of St Peter's and St Nicholas's churches in Nottingham do not appear in the Clergy section, nor are any Roman Catholics or Nonconformists at all to be found there. Dr Philip Boobbyer, the distinguished Medical Officer of Health for Nottingham, does not figure in the book, and one looks in vain also for the headmasters of Nottingham High School or High Pavement School: for the leading local architect Albert Nelson Bromley: or for any members of the Player, Forman, and Shipstone families. There are no professional sportsmen, not even William Gunn, who besides being an England cricket and football international was a prominent enough Nottingham businessman to warrant a place. Nonetheless, Contemporary Biographies was clearly a publication in which many significant people aspired to appear, and where inclusion evidently brought with it a certain cachet. As we shall see, they generally seemed very conscious of their own appearance when sitting for the photographer; no casual, relaxed poses disturb the gravity of this impressively produced volume.

In 1901, the year of the book's publication, Sneinton had long ceased to be a sought-after place in which to live, its rural character being by then almost extinguished. New Sneinton, which contained most of the humblest dwellings, had during the nineteenth century spread up Sneinton Road, joining the old village centre to the eastern fringes of Nottingham, and bringing to the district many cramped streets and courts of hurriedly built terrace houses, the earliest of them back-to-backs. East of the church, extensive building on either side of Sneinton Dale and Colwick Road was under way; this was to create a very decent Edwardian suburb which, though greatly superior to the streets off Sneinton Road, was still by no means fashionable. Not only this, but many of the most picturesque features. of Old Sneinton had lately been obliterated by the demands of housing, transport, and commerce. Sneinton Manor House had gone in 1894, its site gobbled up for the building of Manor Street, St Stephen's Road, and their neighbours. The much admired (at least by those who never lived in them) rock houses of Sneinton Hermitage had been disappearing for about fifteen years, with the construction of the London & North Western Railway's Manvers Street goods branch in the 1880s, and the Great Northern line into the new Victoria Station, which opened early in 1900. The last of these famous dwellings would vanish in 1904. Most of the wealthy Sneinton professional and mercantile families had moved out to newer, more genteel, suburbs of Nottingham, or to nearby villages which were readily accessible by rail, and, rather less so, by road.

In the light of all this it is, perhaps, hardly surprising that no residents of Sneinton appear in Contemporary Biographies. What interest, then, can the book hold in the 1990s for anyone wanting to know more of Sneinton's past? The answer is that, by stretching definitions fairly thoroughly, we can find in it more than a dozen men who had, in their various ways, Sneinton associations.

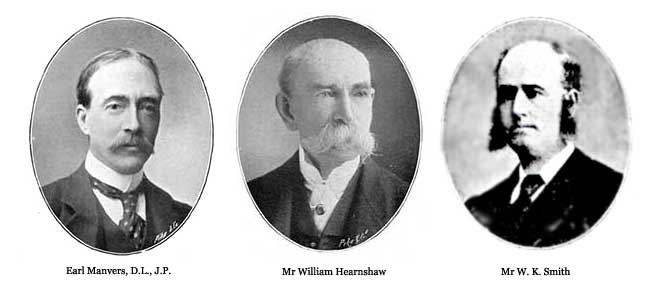

First to be noticed must be Charles William Sydney Pierrepont, 4th Earl Manvers, who had inherited the title only in 1900. His family had long been lords of the manor of Sneinton, and principal landowners here. Though Sneinton Manor House was one of their properties, it had for many generations been let to tenants, the Morleys (of I. & R. Morley, hosiery manufacturers) being especially prominent occupants of the house. Born in 1854, the earl was patron of the living of the parish church, and of several others in Nottinghamshire. His father had been closely involved in the negotiations preceding the building of Sneinton Board School1, and the 4th Earl was to be a major figure behind the foundation of St Christopher's church in Colwick Road2.

Anyone unsure of the extent of the Manvers influence on the Sneinton of the day need only have considered the number of street names associated with the family and its estates - Manvers Street: Pierrepont Street: Newark Street: Kingston Street: Perlethorpe Avenue: Beaumont Street: Thoresby Street: Evelyn Street. The heirs to the Manvers earldom enjoyed the courtesy title of Viscount Newark, and Pierrepont was of course the surname of the family, several of whom had been christened Evelyn. In 1627 Robert Pierrepont had been created Viscount Newark, and a year later, Earl of Kingston-upon-Hull. Evelyn Pierrepont, 5th Earl of Kingston, was created 1st Duke in 1715. Another Evelyn, the 2nd Duke, founded the Duke of Kingston's Light Horse, which was present at the Battle of Culloden in 1746, and took part in the notoriously barbaric suppression of Jacobitism that followed. Thoresby Hall, the grand Nottinghamshire mansion rebuilt in the Victorian period, was the main seat of the family, and Perlethorpe was the Thoresby estate village. Finally, George Beaumont was a loyal servant of the Pierreponts, having been for many years agent to the 3rd Earl Manvers.

It goes without saying that in the book His Lordship appears in the section devoted to Nobility and Gentry; he is second in it after the Duke of Newcastle. Educated at Eton, he was Deputy Lieutenant and a justice of the peace for Nottinghamshire, and a county councillor. As Viscount Newark, Earl Manvers had sat as Conservative M.P. for Newark for a total of twelve years; his tenure as a county councillor would be ended in 1919, when - a real sign of the times - he was defeated by a Labour candidate. He died at his London home in July 1926. In his Contemporary Biographies photograph, the earl regards the camera pleasantly enough with the air of a man happily accustomed to giving orders, and having them obeyed. He has, for his day, a not unduly luxuriant moustache.

Two others in the Nobility and Gentry section have Sneinton connections, but it cannot be denied that, in comparison with Lord Manvers, they represent something of a come-down in the social scale. Rather than belonging to the traditional landed gentry, both were men retired after successful careers, and it might be conjectured that the earl would not have been over-pleased to be listed in their company. One of them, however, was an undisputed native of Sneinton. This was William Hearnshaw of Fox Hill, Burton Joyce, who was born here in 1833, son of a warehouseman of Haywood Street. After attending the old Nottingham Grammar School (later the High School) in Stoney Street, he went to work at Wright's Bank, eventually rising to the rank of manager. Retired since 1898, he was interested in horses, shooting, and poultry breeding, and his son became a national authority on fancy poultry. William Hearnshaw, who died in 1909, displays the most exuberant moustache of our entire gallery.

The next man gets into this account only through his marriage in 1878 to the daughter of a highly-respected Sneinton family. William Keal Smith of Southfield House, Peel Street, Nottingham, was born about 1836 at Ab Kettleby, just over the Leicestershire border. A farmer at Stoke Bardolph and Cotgrave, he had retired during the 1880s. Fortunate enough to be able to describe his occupation in the 1891 census as: 'living on his own means,' Smith was a keen follower of the Quorn and South Notts Hunts. His wife was a Shilton, one of the family who are believed to have built Notintone Place, and who lived in Sneinton House, which lay across the upper end of that once-elegant Sneinton location3. Elizabeth Smith was daughter of Samuel Richard Parr Shilton, and grand-daughter of the wonderfully-named Caractacus D'Aubigny Shilton. Both these worthies are buried close to the east wall of Sneinton church. Samuel, a solicitor of St Peter's Church Side, Nottingham, had been prominent in local government and horticultural circles. William Keal Smith continued to live at Peel Street until 1918, his house becoming a nursing home after his death. He alone of all our personalities is clean-shaven, but sports a pair of the raggedest side-whiskers imaginable, as if to emphasize his rural origins.

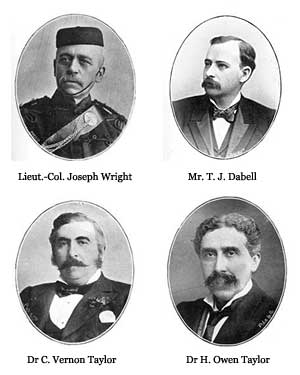

The man with Sneinton connections listed under Military and Volunteers might, had he so wished, have been included in the Commercial section. His place among the soldiery, though, does give us our only glimpse in this narrative of a man in uniform. Joseph Wright of 19 Arboretum Street was born in Nottingham in 1835, and began his working life as an apprentice with the lace house of Heymann & Alexander. He left in his middle twenties to found his own firm of lace dressers and finishers at Dakeyne Street, Sneinton; originally Wright & Co., the business became Wright & Mulholland, with further local premises in Walker Street. Moving to Carlton Road in the 1880s, the business was, under the name Joseph Wright & Co., taken over in 1889 by a limited company. It is still in existence today as Wrights & Dobson Bros., at what was the corner of Carlton Road and Storer Street. By 1901 Wright had interests in a variety of commercial fields, as a director of companies engaged in coal mining, brickmaking, and textile finishing. The founder of one local business house, he married into another, in the effortless way that seems to have characterized Nottingham's nineteenth century merchant dynasties. His wife's father was George Swanwick of High Pavement, partner in Hill & Swanwick, lace manufacturers of St Mary's Gate.

Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Wright, as he is styled in Contemporary Biographies, was a stalwart of the Robin Hood Rifles, having joined as a private at the inception of the Corps in 1859. On the retirement of Sir Charles Seely in 1891 he was offered its command, but declined the honour. In 1900, however, when the Robin Hoods had grown sufficiently to be split into two battalions, he was appointed to command the Second. He had, over four decades, achieved the remarkable record of never missing an inspection or review of the Corps. Keenly interested in politics, he had, like many others, left the old Liberal Party in 1886 over the issue of Irish Home Rule, and was now chairman of the Nottingham and Notts Liberal Unionist Club. He died aged 88, two days after Christmas 1923, having a couple of years earlier seen a knighthood conferred upon his youngest son Bernard Swanwick Wright, for public services to Nottingham. The latter was a solicitor, and leader of the Conervative group on the City Council. Joseph Wright's portrait shows a spruce and alert elderly gentleman with neat grey moustache, in pill-box hat and frogged tunic.

Sneinton associations are also to be found among the medical men listed. Dr Thomas James Dabell, at 37 the youngest man in this survey, had recently acquired a medical practice at 16 Alfred Street South, just around the corner from St Luke's church, Carlton Road, where he had been a churchwarden. St Luke's stood opposite the bottom of Walker Street, and was pulled down in 1925, one of several Sneinton parish churches to close because of a declining population4. A busy man, who served on the Board of Guardians, he sat on the City Council and was sheriff in 1904-05. Dr Dabell was undoubtedly well known to many local residents, remaining in medical practice in Nottingham until after the First World War. In his photograph he wears a natty check bow tie, and without his heavy moustache would look very youthful indeed.

Two rather older doctors were the brothers Charles Vernon and Herbert Owen Taylor, of North Circus Street and Oxford Street respectively. Both educated at Christ Church, Oxford, the former was senior surgeon to Nottingham Hospital for Women, while the latter held a similar post at the General Hospital. Dr H. Owen Taylor had also been surgeon to Nottingham Prison, and to the Midland Railway Company in Nottingham. Like several prominent Nottingham families, the Taylors had burial plots in Sneinton churchyard. Their father, Dr Henry Taylor, was buried here, as, very sadly, were infant children of both brothers. The inscriptions can still be read, revealing that Herbert Owen Taylor and his wife had the tragic experience of losing three babies aged between one and three days, the first in 1880 and twins two years later. Dr Herbert Owen Taylor was Nottingham's first official police surgeon, taking over from his father, who had acted in that capacity without official appointment. In 1886 a police constable who had been bitten by a mad dog was sent by Dr Taylor to Paris, to be treated by Louis Pasteur; the man recovered. Other members of the family succeeded to this position, Taylors continuing as police surgeons until 1952. One intends no disrespect to these worthy doctors in suggesting that their portraits bring to mind the vintage years of the cinema. Dr C. Vernon Taylor has a most prosperous air, surveying the camera confidently; he looks, with his waxed moustache, like a saloon keeper in an old Western. Dr H. Owen Taylor has wavy hair parted in the centre, and one of the finest moustaches in our collection. Some have said that he reminds them of Groucho Marx, but for me he has the bearing of a heavy in a Charlie Chaplin or Buster Keaton silent film.

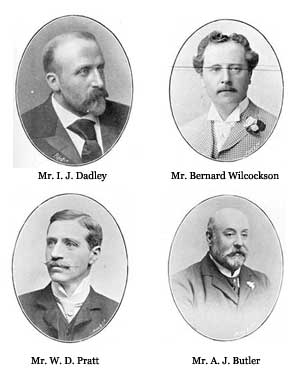

The dentists listed include a man who cured many Sneinton toothaches, the self- styled 'People's Dentist', Isaac Jeffries Dadley, of Carter Gate. The subject of an article in an earlier Sneinton Magazine, this engagingly publicity-conscious man was responsible for some of the most eyecatching late Victorian advertisements put out in the Sneinton area5. These usually featured a giant set of false teeth grinning out from the page, accompanied by lengthy tributes to the efficacy of Dadley's treatments. His practice was for some fifteen years located at the corner of Carter Gate and Stanhope Street, a spot now occupied by the Nottingham City Transport depot, just across the road from the Ice Stadium. Then, in the early part of this century, he moved to smarter and much more central premises in South Parade. His serious, neatly bearded, features perfectly exemplify the character of Contemporary Biographies. The only one of the Dental body not to claim any professional qualification, I.J. Dadley had formerly lived close to Sneinton, in Promenade (off Bath Street) and London Road, but was now resident in West Bridgford.

In the Legal section appears a man born in Sneinton in 1849, whose father deserves lasting credit for providing Sneinton with one of its great treasures. Bernard Wilcockson, a solicitor of 23 Sherwood Rise, was the son of William Henry Wilcockson, who lived for a time in Minerva Terrace, Sneinton Road. The latter was for some years manager of the Nottingham and Nottinghamshire Bank, Thurland Street, and organist and choirmaster at Sneinton church. Sometime in 1847 he acquired for the church the carved mediaeval choir stalls then being disposed of by St Mary's church, Nottingham. Still in St Stephen's, they are the finest examples of mediaeval church woodwork in the city. Several tales, mostly apocryphal, were told, purporting to explain just how the stalls came to Sneinton6. W.H. Wilcockson died in 1887, and was accorded a well-attended funeral at St Stephen's. His grave, now sadly unmarked, is just east of the church, next to the Shiltons; there is also a stained glass window to his memory in the Lady Chapel. Educated at Hurstpierpoint and Oxford, Bernard Wilcockson was a solicitor who practised in South Parade until about 1905; he died at Shanklin in the Isle of Wight in 1911. A very keen musician, he was prominent in local operatic circles. Also known as a composer, he had published such quintessentially Victorian works as The Happy Land valse, and The Rival Blues polka. He presents to the photographer an almost dandified image, with carefully arranged wavy hair, neat moustache, and a flower in the button-hole of his check suit.

We turn next to the section on Architects and Surveyors, to meet William Dymock Pratt, a man with impeccable Sneinton credentials. His father was Nathan Pratt, a maltster of Colwick Road, who later lived in Notintone Place and owned maltings just across the road in Beaumont Street.

Eventually moving from Sneinton to the comparative splendour of Gedling Lodge (now Gedling Manor), Nathan Pratt served for some thirty years as one of the Sneinton churchwardens, and commanded a company of the Robin Hood Rifles in their early days. W.D. Pratt, of Victoria Crescent, Sherwood, had, after qualifying as an architect, gone into partnership with his father's friend J.E. Truman, another great supporter of Sneinton church. Truman & Pratt subsequently designed the extensions to Sneinton Church School in Windmill Lane, and the Church Institute in Notintone Street. During the 1880s, however, Truman took Holy Orders, becoming incumbent of a church in Lincoln, and eventually a Canon of Lincoln.

William Dymock Pratt continued in practice by himself, doing industrial, ecclesiological, and domestic work - he designed, among other things, a number of houses in Mapperley Park - together with a number of civil engineering projects. He also found the time to be titular head of a lace manufacturing firm. He had in 1885 married the eldest daughter of yet another Sneinton notable; this was Alderman Henry Smith Cropper, lace maker and machine builder, member of Sneinton School Board7, and Sheriff of Nottingham. Born in 1854, Pratt continued his architectural practice at Cauldon Chambers, Long Row Central, until his death in 1916. His home was latterly at Bleasby. With meticulously waxed moustache, William Dymock Pratt looks brisk, lively, and agreeable as he poses for the photographer: an appropriate air for a man who listed cycling and tennis among his interests.

The Commercial section of Contemporary Biographies includes a couple of sons of Sneinton, together with two others who owned important industrial concerns nearby. Arthur Joynes Butler, of Mapperley House, Private Road, Sherwood, was born at Sneinton in 1845; his father, Alfred Butler of Sneinton Road and South Street, was a prosperous framesmith. In his teens Arthur entered the lace manufacturing firm of Jacoby & Co., which later occupied one of the grand warehouses in Broadway in the Lace Market, and had factories at Daybrook and Sherwood. Butler became a partner in the business, and eventually its managing director. He also held a similar post in another lace firm, S. Burton & Co. The rich cosmopolitan flavour of the city’s commercial life before the Great War is evoked by the discovery that Mr Butler acted in Nottingham as consul for both Costa Rica and Venezuela. It is diverting to read that, on 4 January 1901, Cipriano Castro, dictator and future president of Venezuela, conferred upon him the decoration of the Order of Busto del Libertador, 4th Class - it all sounds rather like something out of a comic opera. Can there ever have been another local holder of this decoration, one wonders? Arthur Joynes Butler served on the City Council from 1900 until 1913, and was chairman of the Improvement Committee when the decision was taken to widen Carrington Street and Greyfriar Gate. He lived on at Mapperley House until his death in 1921. In his photograph he looks uncommonly like the new king, Edward VII, having the same bald head, neatly-trimmed pointed beard, and rather plump, apparently good-natured features.

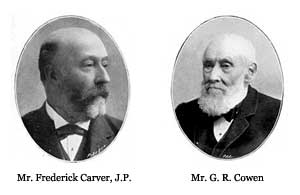

Next to merit our attention, Frederick Carver has his portrait on the page opposite Butler's. In appearance these two could almost be brothers. Carver, by nine years the elder, resembles his fellow-native of Sneinton to a remarkable degree, though his beard is styled slightly differently. Even more than Butler, he reminds one of the king. He was a son of John Carver, maltster of Dale Street and Minerva Terrace, who lies buried beneath a large gravestone in Sneinton churchyard, close to the St Stephen's Road boundary wall. Educated, like Arthur Joynes Butler, at the old Grammar School in Stoney Street, Carver shared the same sphere of industrial life, too, joining the leading Nottingham lace firm of Adams, Page and Cullen, later Thomas Adams & Co. Their magnificent warehouse in Stoney Street was built almost opposite his old school.

Frederick Carver rose to be chairman of the company, and was as prominent in public life as in business, serving as a magistrate and representing the British government in Brussels at an international congress on the management of prisons. He was also a member of the Royal Commission on the 1900 Paris Exhibition. His home was 29 Lenton Road, the Park, where for years his next-door neighbour was Samuel Waite Johnson, the celebrated locomotive engineer of the Midland Railway. His unmarried daughter, Annie Florence Carver, who died in 1922, only four years after her father, left a bequest of £40,000 to Nottingham General Hospital in his memory. This was an very great sum of money, equivalent to about £800,000 in today's values.

The remaining two men to be noticed in the Commercial section of the volume each provided a livelihood for many local people, and both have already figured as central figures in Sneinton Magazine articles. Born in 1818, and another old boy of the Grammar School, George Roberts Cowen of the Ropewalk is by a long distance the oldest of our group. His father founded the Beck Engineering and Ironfoundry in Beck Street and Brook Street, and G.R. Cowen became a partner there in 1844, taking an active role in the business for four decades8. By 1889 it was stated that the firm, occupying 'an eligible site just off Brook Street', had 'advanced from a small concern into one of the first magnitude.' In addition to his industrial achievements, Cowen had an honourable record in public life as town councillor and member of the Board of Guardians. He survived for six years after his appearance in Contemporary Biographies; bald-headed and white- bearded, he peers out rather grimly from his photograph. A director of the Nottingham General Cemetery Company, he and his family are, appropriately, buried beneath a memorial there. The inconspicuous little street named after his family, running between Bath Street and Brook Street, is, regrettably, still misspelt COWAN STREET on its signs, in spite of protests in this and other journals. Unless the proper form is restored, the historical significance of the street name will inevitably be lost.

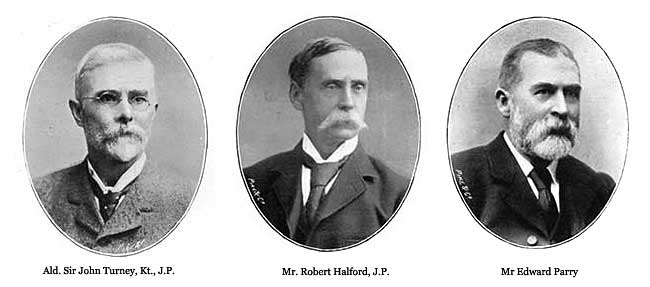

The last industrialist with local connections was one of Nottingham's most prominent men. Born in Old Lenton in 1839, John Turney was in 1861 one of the founders of the leather works of Turney Bros, on the site known as Sneinton Island, at the Trent Bridge end of Meadow Lane9. Here, at this distant corner of Sneinton parish, the tannery became one of Nottingham’s important industrial complexes, and a high proportion of those who lived in the streets off Meadow Lane were among its workforce of over 400. With many other business interests, including the chairmanship of the Raleigh Cycle Co. and the Clifton Colliery Company, Turney was a very busy man who had, by the mid-1890s, made the return Atlantic crossing no fewer than eighteen times. He had a seat on the Town Council for 45 years, serving terms as both sheriff and mayor. Knighted in 1889, Sir John Turney received the Freedom of the City in 1916, not long before his retirement from the Council; he had in 1906 changed his party allegiance from Liberal to Conservative. He lived for some years in Alexandra Park, before purchasing Gedling House, of which he was owner at the time of his death in 1927. With his metal-framed spectacles, neat white beard, and trim hair, Sir John somehow has a surprisingly modern air about him. Nicholas Monsarrat, author of The Cruel Sea and other best-selling novels, was his grandson.

Sneinton could also lay claim to a man listed under Stockbrokers, Auctioneers, and Insurance. Robert Halford of Magdala Road, Mapperley Park, was a partner in Baker & Halford, house and estate agents of St Peter's Gate. He was born in 1840 in Carter Gate, where his father had a cooperage business a few doors down from the Nottingham Castle public house (now The Castle), and just across the road from where the Trent bus garage now stands. The last of our gallery to have been a pupil at the old Grammar School, he was another early member of the Robin Hood Rifles. Halford was articled as a youth to a house agent in Hounds Gate, but in 1865 joined the firm he was eventually to head. His other business interests were formidable in their variety, and a selection must suffice here: director of the Nottingham Church Cemetery Co., chairman of the Nottingham & Notts Bank, of James Shipstone & Sons, and of the Midland Board of the Commercial Union Insurance Company. He was also a director of Notts County Football Club, a magistrate, and an active supporter of local charities.

Mr Halford was emphatically a local lad who had made good; indeed, his will revealed effects amounting to over £191,000, equivalent to about £11 million today. He died at the age of 70 at the end of September 1910, after being at his office earlier in the week. His death and funeral were reported in The Trader of 1 October; this periodical, later The Trader & Citizen, is always worth seeking out, giving as it does an unrivalled picture of the Nottingham business scene of its day. It devotes two pages to a typically detailed account of Halford's funeral at St Andrew's, Mansfield Road, before burial in the nearby Church Cemetery. After outlining his long career, the report sums up Robert Halford in these terms: 'In business as in private and social life he was universally esteemed for his uniform kindliness of heart and for his genial and generous nature. He was a fine type of an English gentleman, and the respect in which the whole community held him was impressively indicated by the attendance on the occasion of the funeral.'

The attendance was indeed quite remarkable; the Mayor and Sheriff, the Chief Constable, a number of magistrates including J.D. and W.G. Player, and J.T. Spalding of Griffin & Spalding: representatives of the Nottingham & Notts Bank, the Chamber of Commerce, Notts County Cricket and Football Clubs, and numerous charitable organizations. About a hundred other mourners were listed, among them members of many of Nottingham's most prominent business and professional families. A similar number had sent floral tributes, among them the men servants and maids at 'Ashtree', the Halford home in Magdala Road. The subject of all these expressions of respect poses rather sternly for the camera in Contemporary Biographies. Although his large, drooping moustache is white, his hair is still dark as he gazes out from his portrait. It may be mentioned that Robert Halford's grandson, Frank B. Halford, became eminent as an aero engine designer; as chairman and technical director of De Havilland, he was responsible for the Ghost jet engines which powered the Comet airliner.

Our last figure, one of the Civil and Mining Engineers, came as something of a surprise, with the last-moment recollection that here was a man who had helped bring about very substantial changes in the Sneinton landscape. Edward Parry of Woodthorpe Grange had worked on the civil engineering staff of the Midland Railway from 1869 until 1879. As assistant engineer on the new main line between Nottingham and Melton Mowbray, he had overall responsibility for construction of the bridge over the Trent at Sneinton. In his classic book The Midland Railway: its rise and progress, the Rev. Frederick Smeeton Williams of Nottingham records how he had interviewed Parry on the spot, learning from him how the piers would be sunk in the river bed, and how water had to be pumped from the foundations of the bridge10. This was the structure now confusingly called Lady Bay Bridge, which following the closure of the railway, has been an essential part of Nottingham's road system.

Over the next ten years Edward Parry was surveyor for the County of Nottinghamshire, while also having a private practice as architect and engineer in Park Row. One of his contracts was as engineer to the Nottingham Suburban Railway, which in the late 1880s further transformed the appearance of Sneinton. Its major engineering works in the neighbourhood included masonry bridges over Trent Lane, Colwick Road, and Sneinton Dale11: a flyover bridge over the Grantham line and girder bridge over the Lincoln line south of Colwick Road: and a tunnel 183 yards long between Sneinton Dale and Carlton Road. It is sad that so little trace now remains of this railway, and that many Sneinton residents are quite unaware that it ever existed.

Parry's local associations are underlined by his chairmanship of the Railway & General Engineering Co. in Meadow Lane, and his directorship of Nottingham Brick Company, which was served by sidings from the Suburban line he helped to build. At the close of the nineteenth century he was resident engineer on the Annesley-Rugby section of the Great Central Railway's London Extension, with oversight of the prodigious engineering works involved in taking that line through Nottingham, including the magnificent Victoria Station.

This enormous undertaking echoed an earlier plan, drawn up by Parry in the 1880s, but never realized. This was for a Nottingham Central Station on a ten-acre site north of the Market Place. It would have occupied the space between the Theatre Royal and Coalpit Lane (now Cranbrook Street,) involving the demolition and realignment of much of Parliament Street. Another of his plans to come to nothing was for a school and lecture hall at Castle Gate Congregation Church, where Parry, as a young man, taught in the Sunday School. Born in Flintshire in 1844, he died at Leamington in 1920. Possessor of a full head of hair and grey beard, Edward Parry is a vigorous final figure in our Sneinton gallery from Contemporary Biographies.

They are, perhaps, a mixed bag - a great landowner: six men born in Sneinton: a doctor and a dentist who practised nearby: two men whose children and father were buried here: three local industrialists: one whose engineering work changed the face of Sneinton: and a farmer who married into a well-known local family. There may be one or two more who have been overlooked. The reader might think that the barrel has been scraped to an unacceptable extent in assembling this collection of notabilities. I accept the rebuke, but remain unabashed, since they are all pieces, however inconsiderable, in the patchwork of Sneinton history. It might be added that, had Contemporary Biographies been published only a year or so later, one man then living in Sneinton could hardly have been omitted. The Rev. and Hon. Robert Macgill Dalrymple, vicar of Sneinton from 1902 to 1917, was a son of no less a personage than the Fourth Earl of Stair. Both as nobility and clergy he would have been certain of a place: assuming, of course, his willingness to pay any inclusion fee that might have been asked.

REFERENCES: all are to items in earlier issues of Sneinton Magazine which give further information about people, places, or events discussed in this article.

1. A bed of nettles: the brief, eventful life of Sneinton School Board SMag 50&51

2. Mission accomplished: the early years of St Christopher's church SMag 49

3. Totally lacking in charm: Sneinton from the air in 1923 SMag 61

4. A low, unpretending building: the story of St Luke's church SMag 19

5. It paid to advertise: the People's Dentist SMag 57

6. Sold for a song: the choir stalls of St Stephen's SMag 27

7. A bed of nettles see 1

8. A plea for Cowen Street SMag 48

9. It paid to advertise: the works on Sneinton Island SMag 60

10. A noble structure: the story of a local railway monument SMag 21

11. Spanning the years: the Dale bridge and its passing SMag 47

Finally, for more about two peripheral figures in this narrative, the Rev. F. S. Williams and S.W. Johnson, the following article may be mentioned:

Midland alliance; railway history in two Nottingham memorials Nottingham Industrial Heritage 11, Autumn 1996.

Stephen Best was born in Nottingham in 1939, to parents married in 1935 at St Christopher's, Colwick Road. His father was born in 1903 at 13 Kingston Street, Sneinton, and his mother lived for some years in Sneinton Boulevard. His paternal grandparents were married at St Alban's, Sneinton in 1897. Of his great-grandfathers, one was born in Sneinton in 1844, and another was a labourer, resident in Pierrepont Street. In that same street in 1851 lived his great-great-grandmother Elizabeth Best, a widowed lace-winder. In more recent years Stephen Best had aunts and uncles in Manor Street, Lyndhurst Road, and Lichfield Road, and himself lived in Dale Grove between 1962 and 1971. He therefore considers his own Sneinton pedigree to be unimpeachable. Like many of the others portrayed here, he possesses a grey beard and a severe expression. The latter may be a result of his realizing that nine of the worthies illustrated were, when they sat for the photographer, younger than he is now.

< Previous