< Previous

SNEINTON or LADY BAY?

How street and place names change

By Stephen Best

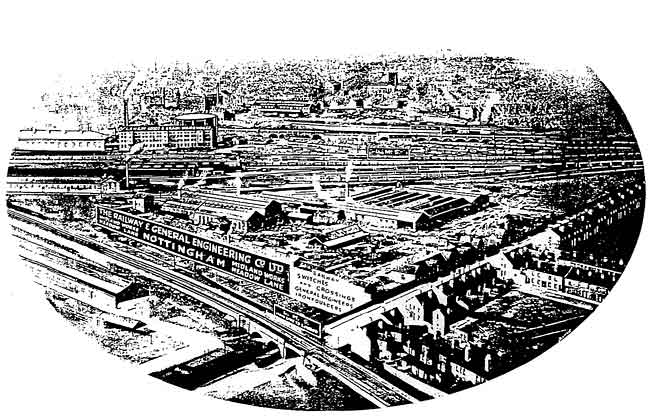

THE SITE OF LADY BAY RETAIL PARK, seen in a 1935 advertisement for the Railway and General Engineering Co. The Railway having crossed the Trent just out of the picture, is carried over Meadow Lane by the bridge in the forground. The sails on Green’s Mill were a product of the fertile imagination of the advertising agency.

THE SITE OF LADY BAY RETAIL PARK, seen in a 1935 advertisement for the Railway and General Engineering Co. The Railway having crossed the Trent just out of the picture, is carried over Meadow Lane by the bridge in the forground. The sails on Green’s Mill were a product of the fertile imagination of the advertising agency. ‘...And gives to airy nothing

A local habitation and a name.’

(Shakespeare. A Midsummer Night s Dream).

SNEINTON PEOPLE MAY HAVE noticed with surprise that the new commercial development nearing completion in Meadow Lane is called ’Lady Bay Retail Park.' However, despite what the developers and local media appear to believe, this location is not in Lady Bay, but in Sneinton. The name of the new complex is nonetheless an interesting example of how place names change, or are blurred, over the course of time, and illustrates one recurring motive for such change over the years. This is the desire to make a place sound rather grander than it really is.

THE TRENT BRIDGE OF THE MIDLAND RAILWAY, now Lady Bay road bridge; an engraving from ’Our Iron Roads’, by the Rev. F S Williams (1883).

THE TRENT BRIDGE OF THE MIDLAND RAILWAY, now Lady Bay road bridge; an engraving from ’Our Iron Roads’, by the Rev. F S Williams (1883).What undoubtedly drew the thoughts of the developers towards the name Lady Bay is the position of the new retail park. This is on the site of the old Railway and General Engineering Co., just across the road from the Sneinton end of what has, for only the last nineteen years or so, been called Lady Bay Bridge. The bridge became part of the Nottingham road network in 1979 following conversion from its former function as a railway bridge. In this role it formed part of the Midland main line from Nottingham to St Pancras, via Melton Mowbray and Kettering. As far as can be ascertained, it was, throughout the eighty-odd years that it served as a railway bridge, never referred to as Lady Bay Bridge. When, in the early 1870s, the Midland Railway proposed construction of a line from Nottingham to Melton, plans were deposited for a branch 'to cross the Trent in the parish of Sneinton.' The railway bridge was invariably identified in official documents, the press, and railway literature by the straightforward, if rather confusing name of Trent Bridge. It still bears evidence of its Midland Railway origins in its stonework; the weathered monogram ’MR’ and the date 1878 are carved at either end, and can be examined at close range from the footpath attached to the west side of the bridge.

LADY BAY BRIDGE on the Grantham Canal, during demolition in October 1960. (Nottingham Local Studies Library).

LADY BAY BRIDGE on the Grantham Canal, during demolition in October 1960. (Nottingham Local Studies Library).My generation grew up knowing a different Lady Bay Bridge. This was a modest bridge in West Bridgford, spanning the Grantham Canal, and carrying road traffic from Radcliffe Road to Trent Boulevard and Holme Road. A 20th century replacement of an earlier bridge, it was demolished in October 1960. The name is much older than the canal, however, and the first Lady Bay Bridge has been identified as flood arches over the Gamston Brook, on the road between West Bridgford and Gamston, a short distance east of the canal bridge site just referred to.

The name Lady Bay has been the subject of theory and speculation over several centuries. It may briefly be described as the area of land in West Bridgford lying between the Trent on the north, and the disused Grantham Canal on the south. The local historian Robert Mellors referred to a document of 1613 mentioning 'our Lady Baie', and suggested that this was the name given to land which lay between the present course of the Trent and its older, slightly more southerly, course. He agreed with the 18th-century historian Charles Deering, who believed that the ancient chapel on Trent Bridge, originally intended to be dedicated to St Mary, might have given its name to the old Trent creek and the fields around it: the bay of Our Lady.

In 1815 John Blackner advanced the rather fantastic theory that the piece of land south of the Trent known as The Hook, once part of Sneinton parish, was pasture for a horse, called either ’My Lady’s bay mare’, or simply 'Lady Bay.' Another explanation for the name was that it came from Alice Palmer, a fourteenth-century restorer of Trent Bridge, and that a bend of the Trent took the name Lady's Bay. Another possible source of the name is that there was a side altar dedicated to the Virgin in the chapel on Trent Bridge built by Alice Palmer and her husband. Yet another theory dates the name to the tenth century when Aethelflaeda, Lady of the Mercians, ordered a burgh, or fortified place, to be built on the south bank of the Trent; it has been suggested that Lady Bay is therefore a version of ’lady's burgh’. None of these explanations totally convinces, but it is likely that between them they contain the truth.

Whatever the real origins of the name, Lady Bay is indubitably part of West Bridgford, and former inhabitants of the now depopulated streets off Meadow Lane - Freeth Street, Grainger Street, Brand Street, Holme Street, and Meadow Grove - would have been astonished to be told that they were residents of Lady Bay. By the time another thirty years have passed, however, this name may well have become firmly attached to the Meadow Lane neighbourhood. A similar thing could happen to Forest Road and the streets around the High Schools; these are gradually becoming referred to by the local press and radio as Forest Fields, which is really a quite different area, on the slopes stretching north from Gregory Boulevard to Gladstone Street.

New names can enter the collective memory very quickly. It is hard to believe that twenty years ago the bridge spanning the river was not yet known as Lady Bay Bridge, and there are even more surprising examples. My great-aunt lived from 1905 to 1970 in Cooper Street, just off Alfred Street Central, right in the middle of what is now universally called St Ann’s. Yet this name was never used by her, and it is doubtful whether she was ever greatly aware of it. This sensible name, taken from the parish church at the heart of the area, and from one of the municipal wards in which the district lay, seems to have been coined only when comprehensive redevelopment was planned in the mid-1960s. Who today, though, would realize that as the name for the neighbourhood, St Ann’s came into general use so recently?

It would, perhaps, be unwise to protest too loudly about such new coinages, for otherwise we should never have become accustomed to the name Sneinton Market. This stubborn survivor and greatly cherished institution has never lain within the strict boundaries of what constituted Sneinton. It is, however, difficult now to imagine the market under any other name.

We can look around Nottingham and see names of areas and streets whose names have been altered through change of fashion, social aspiration, ignorance, or municipal indifference, as well as through an understandable desire to avoid confusion.

All, in their own way, form part of the town's history. As we have seen, Lady Bay shifts to the Sneinton bank of the Trent, while Forest Fields may soon creep over the Forest and impinge on the Arboretum. Two centuries ago Backside became Parliament Street simply to reflect one resident's unufulfilled aim of becoming an MP, while at the beginning of the nineteenth century Cow Lane and Gridlesmith Gate became Clumber Street and Pelham Street, as a respectful nod towards Henry Pelham, 4th Duke of Newcastle, of Clumber Park. The Duke gave some land in that corner of town, in order that Cow Lane could be widened, and in February 1811 received the thanks of the Town Council for his gift.

On the theme of ignorance and indifference, this writer's own frequently-voiced pet source of irritation is the present careless misspelling of Cowen Street, off Bath Street, as Cowan Street. Whatever the uninformed onlooker may think, the street was in fact named after the Cowen family who established the important Beck Engineering and Ironfoundry Works on the site in the early part of the 19th century, and it is high time that the City Council woke up and restored correct street signs to this spot.

At the time of the extension of the Borough of Nottingham in 1877, it was decided that something must be done about the duplication (sometimes triplication and more) of street names which had grown up in the wider Nottingham area. It was all very well for the separate districts of Sneinton, Bulwell, Radford, Lenton, and Basford each to have streets with the same name, but when they all became part of a greater Nottingham, the likelihood of considerable confusion was recognized. So a degree of street renaming took place. In Sneinton, Herbert Street, for example, became part of Beaumont Street, and Dennett Street part of Kingston Street. The nearby Albion Street, Colwick Street and John Street also lost their identities, and were henceforth known as Bentinck Street, Camden Street, and Keswick Street. Streets of the same names as those discarded could be found close by; Herbert Street in the vicinity of Peas Hill Road: Albion Street off Canal Street: Dennett Street off Blue Bell Hill, and Colwick Street just behind Sneinton Market. The other John Street was further away, in New Basford, but St John Street was much closer to Sneinton, and was perhaps felt to be a likely source of confusion.

There was, however, no such excuse for the subsequent removal of a really old and significant Sneinton street name. The Nottingham historian James Granger, always a bitter critic of tasteless and unnecessary name changes, was scathing about the disappearance of Longhedge Lane, which became Gordon Road in 1891. The former name had marked part of the ancient boundary between Sneinton and the Nottingham Clayfield; it was originally simply the Long Hedge, and as such was recorded in the sixteenth century. One assumes that the new name was chosen to reflect the recent fame of General Gordon, the hero of Khartoum, but it is a pity that this venerable local street lost its old identity at all. The Borough Records rather mysteriously indicate that the Borough Improvement Committee renamed Longhedge Lane in response to a petition by residents - had the old name for some reason acquired an unsavoury reputation, perhaps? I do not know.

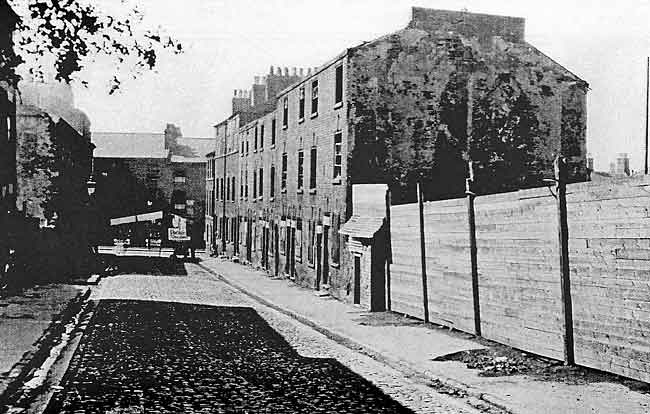

CAMDEN STREET in 1934, with Sneinton Road in the distance. Until the late 1870s, Camden Street was named Colwick Street. (Nottingham Local Studies Library).

CAMDEN STREET in 1934, with Sneinton Road in the distance. Until the late 1870s, Camden Street was named Colwick Street. (Nottingham Local Studies Library).While on this topic, it may be mentioned that well-intentioned people did their best throughout the nineteenth century to expunge the ill-repute attaching to Narrow Marsh by renaming that notorious thoroughfare. It accordingly became Red Lion Street, though the old name reasserted itself for a time, before Red Lion Street was finally adopted in 1905. Then, in the 1930s, complete clearance of the area offered the opportunity of a new start, and the replacement street was given the name Cliff Road. Little good all that did in eradicating the old name from public consciousness and memory; in my youth (about 1950) I was frequently told that I had made our house so untidy that it reminded my mother of Narrow Marsh.

On a wider, and altogether more unstoppable tide of sentiment during the First World War, the city authorities resolved to blot out German street names from the map of Nottingham. Under the newspaper headline: 'Removing the Taint’, it was announced in 1917 that Coburg Road, Hamburg Road, and Mecklenburg Road (off Woodborough Road) were to be renamed Corby, Hampstead and Malvern Road respectively, and that other Teutonic names on the Nottingham street map would be similarly altered. The press reported, however, that the thoroughfares named after the great composers Mozart, Haydn and Handel would be allowed to remain. This news item thus offers the interesting indication that the road from Sherwood to New Basford we all now call 'Haydon’ used to be pronounced 'Hyden.’ It was only to be expected that German street names should become English at a time when even the Royal Family assumed the name Windsor, in place of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha.

Britain's railways, incidentally, were not immune from this patriotic fervour, at least two companies renaming locomotives that bore German names. The London & North Western, though, showed how easy it was for this sort of thing to lapse into parody, when it ordained that an engine inoffensively called Dachshund should be henceforward known as Bull Dog.

We have strayed rather far from Sneinton, but this is a topic on which it is easy to flit from place to place. Returning to our own neighbourhood, however, we may consider two localities which have in recent years demonstrated how names can be either subtly altered, or almost lost without trace. For some unaccountable reason Bakersfields has now turned into Bakersfield; official publications of the 1930s mention it as Baker’s Fields, and as recently as 1961 Nottingham City Libraries, who could, if anyone, have been guaranteed to get a local place name name right, opened the new Bakersfields Library. One remembers officials at the Guildhall subsequently enquiring into the correct form of the name and concluding in favour of the plural. Now, though, we have Bakersfield on the community centre sign, and even more insidiously, on bus destination blinds. Bakersfields seems, sadly, to be a lost cause, even though some present-day street maps give the name as Baker's Fields, while others prefer Baker's Field. All this is, perhaps, of slight importance, but it would cause considerable comment if, over the course of a few years the Meadows, say, were to become the Meadow.

ROYAL OAK HILL, Sneinton Elements, looking towards Carlton Road, about 1950, shortly before demolition. (Nottingham Local Studies Library).

ROYAL OAK HILL, Sneinton Elements, looking towards Carlton Road, about 1950, shortly before demolition. (Nottingham Local Studies Library).Then there is that wonderfully-named outpost of Sneinton parish, Sneinton Elements, which was a little group of streets built on Element Hill, steeply sloping down from Windmill Lane to Carlton Road. After the Second World War, Moodey Street, Royal Oak Hill, Prince Regent Street, and Regent Hill were demolished, and Chedworth Close built over the levelled site. The street names pinpoint the date of the settlement to the 1820s, and there seems no better explanation of the name than that the site was notoriously exposed to the elements on its north side. The old name may have been thought unfashionable (it was undeniably quaint), or there may once again have been some unfortunate association that I am unaware of. For whatever reason, the name would now have disappeared from everyday use, but for the continued existence of Sneinton Elements Post Office in Carlton Road. Long may it survive. If not, it will join in oblivion its close neighbour Sneinton Villa.

CARLTON ROAD in 1861,showing the location of (1) Sneinton Villa and (2) Sneinton Elements: from Salmon’s map of Nottingham.

CARLTON ROAD in 1861,showing the location of (1) Sneinton Villa and (2) Sneinton Elements: from Salmon’s map of Nottingham.Though sounding nowadays more like a football team than a place, this was the original nineteenth-century name for the quarter lying off Carlton Road, in the angle between Alfred Street, Longhedge Lane, Clarence Street and Lowdham Street. Early maps show that quite an elegant street plan was envisaged here. Like the name, however, aspirations of gentility for Sneinton Villa came to nothing. Villa Place, off Lowdham Street, perpetuated the name until the twentieth century; a yard of little houses squeezed in at the side of a malthouse, it can have possessed few graceful features.

Most of us have a particular street or place name whose disappearance or alteration affords special regret. Cowen Street has already cropped up, but let me also mention a couple of Nottingham areas that seem to have gone into the Dead Letter Office. Not long ago people living in streets off Derby Road, such as Rolleston Drive or Kimbolton Avenue, used to give their address as Lenton Sands. Does anyone ever use this highly respectable-sounding name any more? And, as a friend asked while we were discussing this subject, whatever became of Bagthorpe? This was the old name for the area lying between Basford and what we now call Sherwood. I suppose that Bagthorpe Junction on the old Great Central line was the last instance of the name being in general usage, but since the railway closed in the mid-1960s it seems to have all but vanished.

During the thirties Bagthorpe used to appear on the Nottingham City Transport network map as a destination served by buses, but one suspects that socially ambitious residents were eager to rid themselves of a name which reminded everyone that the City Hospital had grown from Bagthorpe Poor Law Institution, and that another less-than-fashionable public building adorned the neighbourhood: Bagthorpe Prison. The old name briefly flickered into life in the middle of the 1980s when it was announced in the 'Nottingham Arrow' that a number of houses had been built on land at Bagthorpe Green which included old railway property, but it seems to have died out again.

THE CROWN INN, Carlton Road, in 1976, before renaming as Smithys. (Photo by Reg Baker: courtesy of Nottingham Local Studies Library).

THE CROWN INN, Carlton Road, in 1976, before renaming as Smithys. (Photo by Reg Baker: courtesy of Nottingham Local Studies Library).There remains one aspect of renaming that can always be guaranteed to stir up strong emotion. This is the fairly recent practice of changing the names of pubs to reflect a corporate image or to climb on a trendy bandwagon. Very often the names chosen are crass and meretricious, reflecting the worst aspects of short-term commercialism. An old pub like the Crown in Carlton Road becomes Smithys, while the Sir Robert Clifton in Bath Street now lurks under the vapid name of B. & E.’s Tavern - a name which one assumes will be changed whenever new licensees take over. It was a pity that the name of Sir Robert Clifton should disappear from the pub map, as this eccentric squire, reckless gambler, and great friend to the licensed trade was a colourful figure in Victorian Nottingham. There was, however, at least some sense in renaming the pub the Market Side, for this is after all where it is, and locals had called it by that name for years. But even this reasonable name has now fallen to the image-makers.

On the same topic, when the long established Fox and Grapes in Southwell Road was renamed, it seemed unfortunate that it was not relaunched as the Prettywindows (or, in Sneinton usage, Prettywinders), which is how everyone locally knew it. Instead it was dubbed the Pegger’s Inn, with a rather unconvincing explanation connecting the new name to a local poaching custom. Similarly, there appeared to be no point in the Nottingham Castle in Carter Gate losing its local identity and becoming The Castle. On the other hand, the Smiths’ Arms in Sneinton Road was usually referred to by locals as The Lamp, so the recent official adoption of that name is natural enough.

Like other parts of Nottingham, Sneinton is not free from pub names like Huckleberry's, always liable to further change at the whim of the publicity industry. Huckleberry's was formerly the Ginger Tom, a name whose loss was not greatly lamented. However, it cannot be said that the current name is an improvement, as Huckleberry’s reflects nothing of the character or spirit of Sneinton. It would, I suppose, be too much to hope that the pub was named after Huckleberry Finn; one suspects that a more recent icon, Huckleberry Hound, is celebrated here.

Even when a renaming commemorates an aspect of local history, a blunder can still be made. For instance, the Turf Tavern in Parliament Street is now named Samuel Morley's. No doubt some marketing consultant was very pleased to discover that the statue of Samuel Morley used to stand close by, in Theatre Square, but it is a pity that further research was not carried out, and consideration given to the fact that Morley, a notable national figure and member of a family highly prominent in Sneinton, was a committed advocate of teetotalism. For the owners to say that it is all a bit of fun, and that no offence is intended, is not good enough. It is a boorish act to name a pub after a man who would have found it deeply offensive. After all, there would rightly be an outcry if a butcher’s shop were named after a prominent vegetarian.

Many sensible people also avoid those pubs whose names are changed to something calculated to provoke a mucky snigger from the immature; everyone knows the kind of name, and there is no need to quote examples. My own own pub nightmare, however, envisages a brewery buying an old inn next door to a Nottingham lace factory, revamping it, and re-launching it as the Firkin & Birkin.

Finally, a cautionary tale. Renamers of all kinds should beware; whether their motive be lofty or commercially sordid, they do not always achieve the result they hope. In this connection there springs to mind the story of the good burghers of Rugeley in Staffordshire. This town attracted unwanted and highly lurid notoriety in 1856 through the sensational trial of William Palmer. He was a young doctor practising in Rugeley, executed for the murder by poison of a bookmaker to whom he owed money. It is very likely that he had previously murdered his wife, several of his children, and his brother. In an episode which is probably apocryphal, but which one would dearly love to have happened, the leading townsmen approached the Prime Minister of the day, asking that Rugeley be renamed, to expunge the stigma brought upon it by Palmer. After reflection, the Prime Minister replied that he would allow this, on condition that Rugeley be instead named after himself. The town worthies thanked Lord Palmerston, but declined his offer.

< Previous