< Previous

IT PAID TO ADVERTISE:

No.3: Horse balls and fine healthy leeches

By Stephen Best

THE FAMILIAR COMMERCIAL SLOGAN of past decades did indeed confidently assert that 'IT PAYS TO ADVERTISE'. In this brief tale, however, we shall be left in doubt to ask: 'But did it?’

The two earlier personalities in this series certainly made advertising pay. Isaac Jefferies Dadley was for many years a busy and well-respected dentist in the Sneinton neighbourhood, while, on an altogether greater scale, Sir John Turney was an internationally successful leather manufacturer. Our third subject is much more difficult to write about, almost all our knowledge of him coming from a single comprehensive advertisement in a Nottingham directory. James Sumner came and went almost without trace, and we have no idea whether or not he made much money. He must, though, have judged the potential market shrewdly enough when setting up his shop in Sneinton, as three successive traders followed him in the same trade, and at the same address, for some five decades after his departure.

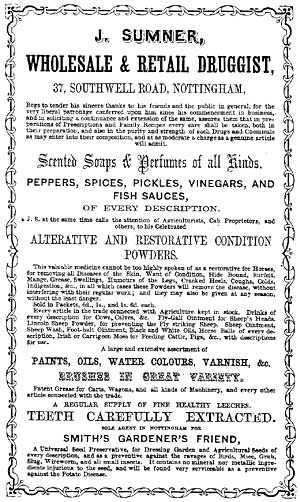

Throughout the nineteenth century, very few Sneinton shopkeepers took out display advertisements in the Nottingham trade directories, published every year or two. Most of the prominent adverts were for businesses in the centre of town, which could expect to catch the eye of the greatest number of potential customers. In Wright's Nottingham Directory, and Borough Register, for 1854, however, is one which heralds the recently established Sneinton business of a manifestly ambitious proprietor. Typical of many Victorian advertisements, it must have taxed considerably the printer’s stock of type faces.

It may be mentioned in passing that the directory publisher, Christopher Norton Wright of Long Row East, occupies his own small niche in Sneinton history, having erected in the churchyard a headstone in memory of the first two of his four wives, both buried here. The first Mrs Wright had the rare and melancholy distinction of dying only two days after her marriage. An attempt to disentangle the grotesquely complicated story of the Wright family can be read in Sneinton Magazine no. 20. The publisher's son C.N. Wright, junior, of George Street, was the printer responsible for the physical layout of the directory. Like most printers of Victorian advertisements, Wright could not be accused of niggardliness in his use of capital letters, as a glance at the volume will make clear.

The notice in question, occupying a full page, announces that J. Sumner, 'WHOLESALE & RETAIL DRUGGIST,' is in business at 37 Southwell Road, Nottingham. At the outset, the earnest Sumner 'Begs to tender his sincere thanks to his friends and the public in general, for the very liberal patronage conferred upon him since his commencement in business, and in soliciting a continuance and extension of the same, assures them that in preparations of Prescriptions and Family Recipes every care shall be taken, both in their preparation, and also in the purity and strength of such Drugs and Chemicals as may enter their composition, and at as moderate a charge as a genuine article will admit.’

Clearly, then, a responsible practitioner, and no doubt an ornament to the town. But a puzzle immediately arises. Although Sumner's name appears on his large advertisement and in the classified list of druggists in the directory - where his first name is given - no one of this surname is listed under Southwell Road in the street list. What is even odder, 21 is the highest- numbered property in Southwell Road. Was the address, then, a printer's error? Such a theory seemed improbable, given that the 1855 directory (not published by Wright) repeats the information that James Sumner was at 37 Southwell Road. This, though, is all we shall find in print about Sumner; after these two brief appearances in 1854 and 1855 we lose track of him for ever.

Where James Sumner came from, and whither he went, has so far proved impossible to discover. He cannot be identified anywhere in the Nottinghamshire censuses of 1851 or 1861, so his stay in the county appears to have been a short one. No one of this name died in Nottingham or the surrounding area between 1854 and the date by which another man had taken over his business. Nor does a check of the later 1881 census reveal any James Sumner living in Nottinghamshire or its neighbouring counties who seems likely to have been the chemist. A search of the probate registers at the Public Record Office in London has proved equally fruitless in trying to run him to earth.

A chance find did, however, reveal the location of his shop. During a search of the 1861 census for something entirely different, a stray entry for a single household in Southwell Road came to light. The house was numbered 37, and with the occupant describing himself as a chemist and druggist, it was evident that here was Sumner's successor.

This was Joseph Lewis, aged 35, married with one child. That the business was prospering well enough in 1861 may be judged from the census details. In addition to the Lewis family, 37 Southwell Road was home to a living-in chemist's assistant, as well as to two apprentices. Lewis, who had owned the shop since 1858 at least, was to remain here for about twenty years, though we hear no more of 37 Southwell Road. The premises were thereafter listed as no. 20, as they should logically have been all along, and take their place in correct sequence within the street directories. Once or twice, however, compilers seem to have had trouble deciding whether the shop was in fact no. 20 or no. 18, giving rise to the suspicion that no number was displayed on its frontage.

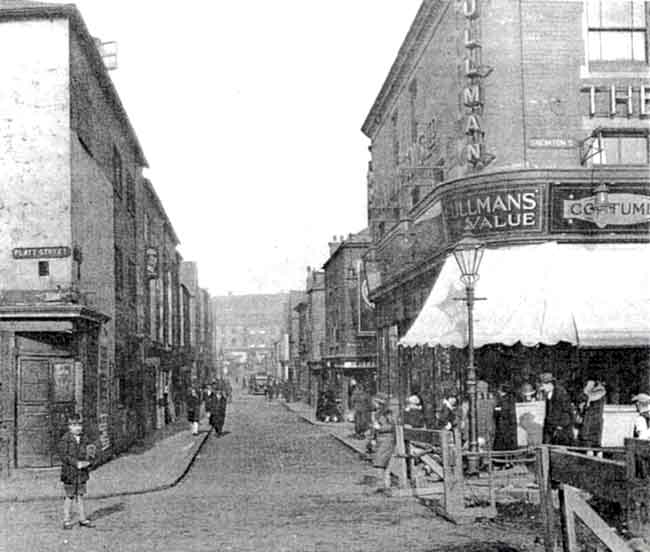

Joseph Lewis had clearly been keen to expand his business activities. Before taking over from Sumner at Southwell Road, he had as early as 1854 owned another druggist’s shop nearby at no. 1 Gedling Street, close to its junction with Platt Street and Sneinton Street. For a couple of decades Lewis ran both establishments, but by 1881. had disposed of the Southwell Road premises to another chemist, retaining his Gedling Street concern.

This third chemist and druggist to ply his trade in Southwell Road was Ambrose Middleton, who opened several other shops, and was in 1895 running no fewer than three additional premises: in Middle Marsh, Lister Gate and Drury Hill. Four years later Middleton had installed a manager at Southwell Road, where he also traded as Middleton & Co., oil and colourmen. Very soon after the turn of the century, however, Middleton had concentrated his activities on the Lister Gate and Middle Marsh shops, and a firm called Hogg & Co. had taken over from him at 20 Southwell Road. Their term of ownership proved to be very short, and the 1905/6 directory is the last indication we have of them, or indeed, of any chemist, at Southwell Road.

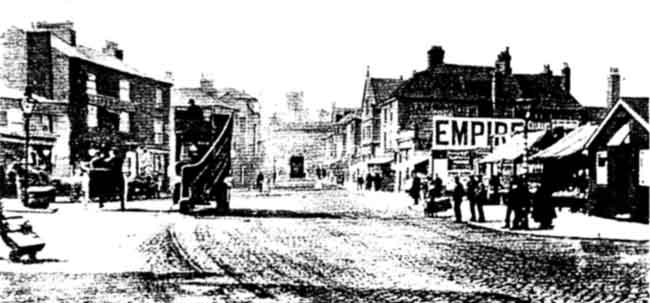

SOUTHWELL ROAD about 1906, with St Mary’s church on the skyline. The shop of Sumner and his successors, which closed down very near this date, was in one of the buildings immediately to the right of the motor bus.

SOUTHWELL ROAD about 1906, with St Mary’s church on the skyline. The shop of Sumner and his successors, which closed down very near this date, was in one of the buildings immediately to the right of the motor bus.The immediate neighbourhood of Southwell Road had, as we shall see, been bad enough during the nineteenth century. By the early 1900s it was becoming even more poverty-stricken and run down, so perhaps some shopkeepers reckoned that it was now time for them to move out. For all that, the little dynasty begun here by James Sumner had evidently been a profitable one for almost fifty years. His advertising had undoubtedly paid off for someone, if not for himself.

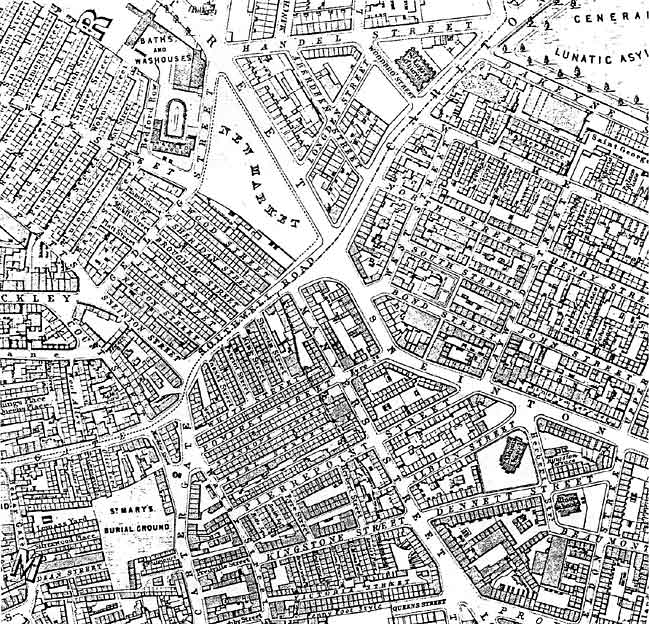

The 1854 directory lists no fewer than 48 druggists in Nottingham and Sneinton. Several of these were quite close to Southwell Road: in Manvers Street, Sneinton Road, Sneinton Street, Carter Gate, Beck Street, Cross Street, and Gedling Street - the last being Lewis’s other premises. In the face of all these businesses, Sumner's shop may at first sight seem to have been an unnecessary competitor - in every sense a drug on the market. A glance at a large- scale map of the time, however, helps to put it in context. Within two or three hundred yards of Sumner's shop door were, at a moderate estimate, some 500 back-to-back homes, none of them more than a five- minute walk away.

Indeed, in the middle of the nineteenth century Southwell Road lay in a very crowded, and severely deprived, part of Nottingham. The chemist's premises were squeezed in on the street frontage between Manvers Street, Quinton's Yard, and Sherwin Street, right on the boundary dividing Sneinton from Nottingham. Though their close neighbours, just around the corner in Manvers Street, were situated within Sneinton parish, Sumner and his successors were technically residents of the Borough of Nottingham. They were, nonetheless, in the heart of a part of town that always seemed the very essence of Sneinton.

POMFRET STREET in February 1914, just before demolition. This was typical of the very poor streets of back-to-back houses within a short distance of Sumner's shop.

POMFRET STREET in February 1914, just before demolition. This was typical of the very poor streets of back-to-back houses within a short distance of Sumner's shop.Quinton's Yard, immediately west of the shop, contained a maltings, and perhaps a wood store too, for its owner Hezekiah Quinton was a timber merchant as well as a maltster. Like a number of prosperous business people in and around Victorian Sneinton, however, Quinton lived some distance away from his work; he resided in gentler and cleaner surroundings at Wilford.

Sherwin Street (not long afterwards renamed Sun Street) ran south from Southwell Road into a cramped and crowded area of wretchedly poor homes, almost all of them back-to-back houses. Eventually designated the Carter Gate Unhealthy Area, this was cleared around the time of the Great War. The municipal authorities had described it as one of the most desperately insanitary and needy parts of Nottingham, its dwellings 'unfit for human habitation.' The City Transport bus depot now occupies much of the land on which these houses stood.

Across Southwell Road from the chemist, another tract of back-to-back streets was, incredibly and disgracefully, to survive into the 1930s, before being razed to make way for Sneinton Wholesale Market. There were over 200 houses here, crammed into a two- acre site; in Lucknow Street 36 houses shared one outside cold water tap, and pail closets each served two houses. Beyond these streets, and lying on either side of Colwick Street (now Brook Street), was a further quarter containing dreadfully poor houses, including the notorious Meadow Platts, yet another of Nottingham's unhealthiest areas.

It requires little imagination, therefore, to realize that a great number of people lived nearby who must have had constant need of chemists and druggists, though it must be doubted whether most of them had the means of paying for these necessary goods and services.

Anyone wishing to visit the present-day site of Sumner's business should stand outside the tattooist’s studio in Southwell Road; this is, as near as one can judge, where the chemist’s front window would have been in the 1850s. It is, however, not easy to imagine what the place was like in the 19th century; the Peggers pub, long the Fox and Grapes, and at the time of writing recently renovated, is the only building in Southwell Road surviving from before the turn of the century.

SOUTHWELL ROAD and its environs, as shown on Salmon’s map of 1861.

SOUTHWELL ROAD and its environs, as shown on Salmon’s map of 1861.But it is time to return to the advertisement, which is what this account is really all about. Wonderfully evocative of its time, it reveals just how different the business of an urban chemist and druggist was from that of his modern counterpart. At the same time it highlights features of life in and around Southwell Road which have long since vanished from Sneinton.

We left James Sumner thanking customers for patronising his shop, and assuring them of his care in dispensing prescriptions. His advertisement goes on to draw attention to two further ranges of goods he has for sale, one of them rather more unexpected than the other. While it is no surprise that a chemist should have stocked 'Scented Soaps and Perfumes of all Kinds,' the late twentieth century reader may be less prepared to find that such an establishment sold: 'PEPPERS, SPICES. PICKLES, VINEGARS, AND FISH SAUCES, OF EVERY DESCRIPTION.’ It is not easy to imagine residents of, say, Pipe Street or Vassal Street sending their ill-fed children round to the chemists with a penny to buy fish sauces. No doubt many of Sumner's sales in such lines were wholesale to the trade. He was certainly not the only chemist in the directory to advertise them, so they were evidently in steady demand, and routinely part of a druggist's stock-in- trade. It has been suggested to me that people struggling along on a poor and unappetizing diet might well have disguised the paucity of their food with tasty sauces; even so, one would expect these to have been available from a grocer rather than a chemist.

Sumner was by no means finished yet, and his advert is still gaining momentum with mention of products directed at sufferers other than human. U.S. at the same time calls the attention of Agriculturists, Cab Proprietors, and others, to his Celebrated Alterative and Restorative Condition Powders'. One tends to forget just how much the horse dominated nineteenth-century Nottingham. All goods not pushed around on a barrow, or carried manually, were hauled about the town by horses; and people not wishing to walk through the streets either went on horseback, hired a cab, or rode in a private carriage. Horse buses ran to destinations such as Arnold and Beeston, while carriers, usually departing from inns in the centre of Nottingham, served about 140 local towns and villages on a regular basis. The directory shows 29 cab proprietors and livery stable keepers in the town in 1854, together with about a dozen farriers and shoeing smiths.

Other livestock was plentiful hereabouts, too. In Nottingham were numerous butchers who raised their own beasts nearby, killing them in small slaughterhouses, often sited very close to domestic premises; seven cowkeepers are listed in the directory for Sneinton alone. Animals were frequently driven through busy streets, with occasional mishaps when a frightened animal ran amok. In the very same year that James Sumner placed his advertisement, an enraged bullock ran riot along Parliament Street, Thurland Street, Pelham Street, Clumber Street, and the Poultry. In the course of this rout it broke a shop window, and attacked several passers-by; one of them, with rare and piquant appropriateness, a butcher.

GEDLING STREET about 1929, looking towards Bath Street. Joseph Lewis’s first chemist's shop had been at no.l, one door up from the Platt Street corner.

GEDLING STREET about 1929, looking towards Bath Street. Joseph Lewis’s first chemist's shop had been at no.l, one door up from the Platt Street corner.James Sumner is lavish in the claims he makes for his condition powders; surely a remarkable bargain at 6d, if they did all that was claimed for them. 'This valuable medicine,' we read, 'cannot be too highly spoken of as a restorative for Horses...' The preparation cured animals that were hide bound, or suffering from surfeit, mange, grease, swellings, humours of the legs, cracked heels, coughs and colds, etc. An additional selling point was that the powders were said to effect a cure without interfering with the horses' regular work; the hard-pressed cab owner and stable keeper doubtless found such a miracle remedy difficult to resist. For any reader as uninformed as this writer about animal disorders, it may be helpful to know that grease is an inflammation of the heels; mange an inflammation caused by mites; while a hide-bound horse suffers, through incorrect feeding, in having its hide attached too closely to the back and ribs, so that it becomes taut, and not easy to move.

Nor did Sumner's stock overlook other beasts likely to be found in the vicinity of Southwell Road in 1854. He advertises: 'Drinks of every description for Cows, Calves, &c. Fly-Gall ointment for Sheep's Heads. Lincoln Sheep Powder, for preventing the Fly striking Sheep. Sheep Ointment, Sheep Wash, Foot-Halt Ointment, Black and White Oils, Horse Balls of every description, Irish or Carigeen Moss for Feeding Cattle, Pigs, & c...' To explain further, fly galls are swellings caused by blowfly, and foot-halt a dialect term for foot-rot. It hardly needs saying that horse balls, or boluses, were large medicinal pills for curing equine maladies.

A different facet of Sumner's activities is introduced with the announcement that he stocks 'A large and extensive assortment of PAINTS, OILS, WATER COLOURS, VARNISH, &c. BRUSHES IN GREAT VARIETY.' The selling of artists' materials may seem a curious branch of the chemist's profession, but this was another recognized line for such traders. Two of the later owners of Sumner's shop, Ambrose Middleton and Hogg & Co., were also in the course of time to style themselves as oil and colourmen. Though the word 'colourmen' may, to the lay person, now have rather an unfamiliar ring about it, it was a common enough term for Arthur Conan Doyle to call one of the Sherlock Holmes stories 'The Retired Colourman.'

At this point in his advertisement Sumner seems to remember that he has earlier promoted his horse cures, and so proceeds to catch the eye of any cab owner or carter whose vehicle requires attention as urgently as his horse. Our resourceful chemist, not to be found lacking in any needful and relevant item, slips in the information that he stocks a range of: 'Patent Grease for Carts, Wagons, and all kinds of Machinery, and every other article connected with the trade'.

These notices about paints and wagongrease, though undoubtedly of interest to many of Sumner's customers, may, as already suggested, appear peripheral to the essential profession of chemist and druggist. We return with a bump, however, to two aspects of the Victorian chemist’s work which must have been regarded with trepidation by prospective patients. Their promulgation is given without any frills, evidently requiring no further explanation:

'A REGULAR SUPPLY OF FINE HEALTHY LEECHES', we read, and 'TEETH CAREFULLY EXTRACTED.' The leech, a blood-sucking annelid worm, had long been used by medical practitioners to bleed patients, but its general application in orthodox western medicine was already in decline by the middle of the nineteenth century. It is, however, now making something of a comeback as we near the end of the twentieth.

Victorian residents of Sneinton were quite familiar with these unattractive creatures. Indeed, Mr Edward Stevenson, writing to the Evening Post in 1947, had a vivid recollection to share. His grandmother, the wife of the Sneinton blacksmith, Thomas Stevenson of Dale Street, 'always kept a jar of leeches under the kitchen sink for curing black eyes... ' People were no doubt less squeamish in those days. Somehow, though, it is rather disquieting that James Sumner feels it necessary to state that his leeches are fine, healthy ones - being subjected to treatment with unhealthy specimens is the stuff of nightmare.

We come now to the extraction of teeth. Sufferers from toothache were, one trusts, reassured to be told that this was done carefully at Sumner’s. This could not, in 1854, be taken for granted everywhere. In that year there were, according to the directory, nine dentists practising in Nottingham, but many people then, and for some little time afterwards, would consult a local chemist and druggist over their dental problems. The latter practitioners mainly extracted teeth and supplied false ones to take their place; fillings, though, were generally available only to those privileged enough to be able to pay for specialist treatment.

For its finale, the advertisement abruptly moves from bloodletting and the removal of teeth into yet another field of human endeavour. We are told that Sumner is sole agent in Nottingham for 'SMITH'S GARDENER'S FRIEND.' This versatile preparation is described as: 'A Universal Seed Preservative, for Dressing Garden and Agricultural Seeds of every description, and as a preventive against the ravages of Birds, Mice, Grub, Slug, Wireworm, and all small insects. It contains no metallic ingredients injurious to the seed, and will be found very serviceable as a preventive against the Potato Disease.'

This last claim would have been particularly compelling in 1854, only five years after the end of the appalling Irish potato famine. Caused by the arrival of the American potato blight, the famine was principally responsible, through death and emigration, for a 20% decline in the population of Ireland between 1841 and 1851. I have not been able to find out how long Smith's Gardener's Friend remained on the market, but have little doubt that it commanded a ready sale. Had it also guaranteed to keep cats out of gardens it would, I suggest, indeed have been a horticultural product without peer.

Here, then, we have the entire spectrum of James Sumner's goods and services. As we have seen, they range on the medical side from the preparation of prescriptions to the removal of teeth and the supply of leeches. Animals are catered for by condition powders, drinks, ointments, washes, pills, and moss for feed. The human palate is supplied with spices, sauces, and condiments, and the artist's palette with paints, water colours and brushes. Grease is available for the maintenance of vehicles and machinery, and seed preservatives for the Sneinton garden. It is hard, after reading his advertisement, to see how Sneinton could ever have managed to do without a James Sumner, and it is good that his shop was taken over by three other chemists and druggists in turn, to remain open until the first decade of the twentieth century.

Writing this small episode of local history was a fascinating, though tantalizing task. It would be a great reward to discover what became of Sumner, but, as already explained, that cannot be. As said at the outset, so little is known about him that we cannot even be sure that he bore out the promise of the article's title, and found that it really did pay him to advertise.

We can, however, at least be grateful that James Sumner chose to place his advertisement in the directory, and through it enabled us to savour something of the rich variety of Sneinton life in the year 1854.

HOW LATE 19th century NOTTINGHAM was dominated by horse-drawn traffic. Carts are lined up awaiting their horses at a carrier depot in Upper Parliament Street. The large Co-op store now stands on this site.

HOW LATE 19th century NOTTINGHAM was dominated by horse-drawn traffic. Carts are lined up awaiting their horses at a carrier depot in Upper Parliament Street. The large Co-op store now stands on this site.My thanks to Philip Jones for his attempts to establish the date of Sumner's death, to Ken Brand for his usual helpful comments, and to Nottingham Local Studies Library and Nottinghamshire Archives Office for customary hospitality.

This little history is inscribed with love to Joyce Hather, who after living here, and serving the community for many years, has recently moved house from Sneinton. It is good to hear that she has found another reliable chemist to take the place of the exemplary pharmacist she left behind her.

Nos. 1 and 2 of IT PAID TO ADVERTISE appeared in Sneinton Magazine issues 57 and 60.

< Previous