< Previous

PICTURESQUE AND WORTHY OF INSPECTION:

Sneinton echoes in the Church Cemetery, Nottingham

By Stephen Best

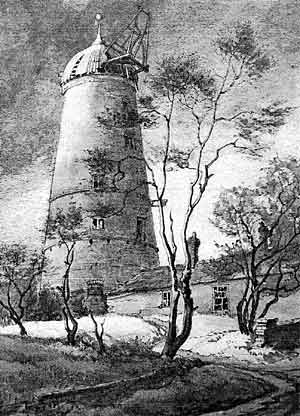

THIS WATERCOLOUR OF GREEN'S MILL by A L GILBERT was done in 1919, the year of Clara Green’s death. William Oakland also worked the mill for several years before moving to another, close by.

THIS WATERCOLOUR OF GREEN'S MILL by A L GILBERT was done in 1919, the year of Clara Green’s death. William Oakland also worked the mill for several years before moving to another, close by.OVER THE YEARS STORIES HAVE appeared in Sneinton Magazine, telling of interesting people who are buried in St Stephen's churchyard. Not all of these had lived locally, however. In the late eighteenth century, for instance, some prominent men with only tenuous Sneinton connections directed that their remains be interred in what was still a picturesque and rural spot.

On the other hand, plenty of colourful men and women closely associated with Sneinton are buried elsewhere in Nottingham. Indeed, after Sneinton churchyard was declared full in 1897, and closed for further burials (except in existing family vaults), the vast majority of its people could no longer choose to be buried in their own parish. This state of affairs partly, though not entirely, explains the presence of a number of memorials associated with Sneinton in the two great burial-grounds of 19th and early 20th century Nottingham. Sometimes the Sneinton link is clear in the monumental inscription: in other cases one has to be on the lookout to spot it. The histories behind some of these gravestones are worth recounting.

The General Cemetery, extending downhill from its main entrance in Canning Circus, is the older of these two, the first burial having taken place there in 1837. This article, however, takes a brief look at the Church (or Rock) Cemetery in Forest Road, nineteen years its junior. Not far from the entrance gates at the corner of Mansfield Road, and just beyond the truncated remains of the lodge, an especially famous Sneinton surname can be found on a small white stone by the Forest Road railings. This reads as follows:

IN

MEMORY OF

CLARA GREEN,

DAUGHTER OF THE LATE

GEORGE GREEN, M.A.

OF CAIUS COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE,

AND FORMERLY OF SNEINTON.

DIED 6th MARCH 1919,

AGED 78 YEARS

Many old Sneinton families will, like my own, have heard stories about this lady in her last, sadly eccentric, years. She was the fifth daughter and youngest child of the great mathematician and physicist, and of Jane Smith (later called Jane Green), who bore seven children by him, though they never married. Clara was born in Sneinton in May 1840; her father died when she was only just over a year old, and it seems surprising that he left the Green family house on Belvoir Hill to his infant daughter. Clara, however, would live for some years with her mother at the house she occupied in Notintone Place, where George Green had died at no. 3 in 1841.

In 1879, when her sister married, Clara became the last member of the Green family family left in Nottingham, her mother having died in 1877. She was, as just mentioned, legal owner of the house by the windmill, but by necessity had to let it out to tenants and live on the rents. Local people recalled that she had for a time in the early part of the twentieth century been a paying guest in the house she owned; it was also believed that she had earlier been governess to members of the family of the Rev. W.H. Wyatt, vicar of Sneinton from 1831 to 1868.

Clara had, on her brother's death in 1850, also inherited a sixth share of the mill. By 1870, through the deaths of other siblings, this sixth had increased to a third. Lack of money to keep the mill in good repair, however, meant that it had already become derelict before that date.

For about the last three years of her life Clara Green lived in a sort of summerhouse on her property, close to where Finsbury Avenue runs, off Sneinton Dale. All her life she must have been aware of what was then the very real stigma of illegitimacy. Children living nearby would enrage this strange, lonely old woman by shying stones at her: she would sometimes reward them by threatening them with a sweeping brush. Aged 78, she took ill, dying just over a week after being removed to Bagthorpe Workhouse Infirmary (nucleus of the City Hospital.) It is awful to read that during the 1930s the vicar of Sneinton, the Rev. J.R. Thomas, heard from old parishioners that they had, towards the end of her life, helped Clara burn Green family papers.

Perhaps a personal note may be inserted at this stage. During the 1980s I combed the Church Cemetery, photographing every stone of special interest that I came upon. An account of these finds was printed in a series of articles, until only the final part remained to be published. It was then that Mary Cannell remarked that that Clara Green's stone would no doubt be mentioned in it. I had fondly thought I had spotted everything of importance, but until then had no idea that Clara's headstone existed. Having received directions from Miss Cannell, I returned to the cemetery and duly found the memorial. It had, I think, been neglected and overgrown when I first missed it, but this is little excuse. It is a salutary lesson for any local historian: however confident you may be that you have exhausted the well of knowledge, there always remains something to be discovered.1

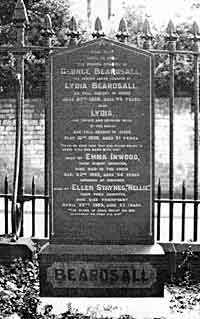

THE GRAVESTONE of GEORGE and LYDIA BEARDSALL, with the Forest Road railings of the cemetery behind.

THE GRAVESTONE of GEORGE and LYDIA BEARDSALL, with the Forest Road railings of the cemetery behind.A couple of minutes' walk further along by the Forest Road railings brings the searcher to another memorial linking Sneinton with a famous name. This time, however, that celebrated person did not come from Sneinton, and it is with his grandparents that we are concerned here. Theirs are the first two of four names to appear on the stone:

HERE REST

UNTIL HE COME

THE MORTAL REMAINS OF

GEORGE BEARDSALL

THE DEARLY BELOVED HUSBAND OF

LYDIA BEARDSALL

HE FELL ASLEEP IN JESUS

JUNE 27th 1899, AGED 74 YEARS.

ALSO

LYDIA

THE LOVING AND DEVOTED WIFE

OF THE ABOVE.

SHE FELL ASLEEP IN JESUS

MAY 16th 1900, AGED 71 YEARS

The inscription suggests a pious couple, as indeed they were. Lydia Beardsall was the second daughter of John Newton, a lace twisthand, of Haywood Street, Sneinton. Newton’s enduring claim to fame is as a prolific composer of hymn tunes, several collections of which were published. For a time he was choirmaster at Parliament Street Methodist Church.2

By the date of her marriage to George Beardsall, at Sneinton parish church on Boxing Day 1847, Lydia had moved the short distance to Henry Street, just round the corner from Haywood Street. Beardsall was then in his early twenties, a few years older than his bride. A mechanic, he worked for bobbin and carriage makers in Butcher Street, between Manvers Street and London Road. Beardsall was a zealous Methodist with the reputation of a difficult man; indeed, he quarrelled with Jesse Boot and William Booth, which must represent a unique double. His work having taken him and his his wife away from Nottingham, three daughters were born to them in Manchester. George Beardsall later obtained the job of engineering foreman at Sheerness Dockyard, and while in Kent the family further increased.

By 1871, the couple, now with six children, were back in Sneinton, at John Street, later renamed Keswick Street. Beardsall was by this time described as an 'engine-fitter (superannuated)'. Their eldest daughter, also Lydia, was now 19 years old, and it is upon her that the spotlight now turns. Having worked for a time in Sheerness as a very young teacher, she was obliged on arrival in Sneinton to seek a living as a lace drawer, a decline in status that no doubt she felt keenly.

In 1874 Lydia Beardsall met Arthur Lawrence, from Brinsley, a miner employed at Clifton Colliery. On 27 December 1875 the couple were married at Sneinton church, just 28 years and one day after the wedding of Lydia's parents there. The Lawrences lived for a time in Radford, and then Sutton-in-Ashfield, before moving to Eastwood. There, in September 1885, their fourth child David Herbert was born. George and Lydia Beardsall of course died before their grandson could make his name as novelist, short story writer, playwright and poet; and there is no saying what they might have made of him. This is not the place for considering D.H. Lawrence's merits as a writer, but there can be no doubt that, through his mother, he was deeply informed by the Nonconformist religious culture of his grandparents and great-grandfather.

One wonders how many times Lawrence visited the grave of his Beardsall grandparents. It is not known whether the headstone was put up before their daughters Emma and Ellen had died in 1903 and 1908, but the young Bert was within easy reach of the cemetery at the time of the deaths of George and Lydia. From 1898 until 1901 he was a Scholarship boy at Nottingham High School, just across Forest Road from the Church Cemetery.

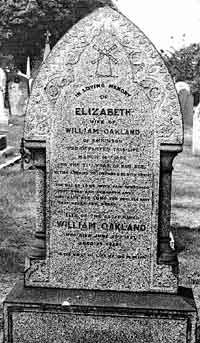

THE CARVED WINDMILL on Oakland's headstone recalls his former occupation as miller.

THE CARVED WINDMILL on Oakland's headstone recalls his former occupation as miller.Between the Green and Beardsall memorials, adjacent to the site of the demolished cemetery chapel, stands another stone with a very strong Sneinton association. It is not very easy to make out, but is well worth the effort of discovery. William Oakland was a miller on Forest Side, at one of three mills on the land that eventually became the Church Cemetery. These three formed part of a long row of thirteen mills which stood (though never all at the same time) along the prominent ridge which is now Forest Road. The last of these was pulled down in the late 1850s. Oakland's grave is, according to long tradition, on the site of his mill.

On leaving the Forest, Oakland took over Green's Mill at Sneinton, until it closed through a dispute concerning its ownership and consequent responsibility for repairs. Long before they lay buried so near to one another, therefore, William Oakland and Clara Green were both caught up in this business tangle. With Green's Mill no longer workable, Oakland moved two or three hundred yards up Windmill Lane to a post mill, sited opposite the grounds of the General Lunatic Asylum, and just where Sneinton Church School now stands.

Oakland worked this latter mill until 1881, when he unsuccesfully advertised it to let. He died in 1887, five years after his wife. As we shall see, there is some evidence that Mrs Oakland's last years had been difficult ones. Before the modern revival of Green's Mill, William Oakland was, as far as can be ascertained, Nottingham's last active miller.3

Obtaining a satisfactory photograph of Oakland's gravestone presents a stiff challenge; this writer was once reduced to filling in the outline of the windmill with chalk, in order to capture it on film. It is hoped that the shades of Mr and Mrs Oakland were not offended by this act.

Oakland's gravestone, of pink granite, is notable for bearing a depiction, if a rather naive one, of a windmill. Its inscription reads:

IN LOVING MEMORY

OF

ELIZABETH

WIFE OF

WILLIAM OAKLAND

OF SNEINTON,

WHO DEPARTED THIS LIFE

MARCH 16th 1882

IN THE 71st YEAR OF HER AGE,

HAVING A DESIRE TO DEPART AND BE

WITH CHRIST

SHE WAS SO LONG WITH PAIN OPPRESSED

THAT WORE HER STRENGTH AWAY

AND MADE HER LONG FOR ENDLESS REST

THAT NEVER CAN DECAY

ALSO THE ABOVE NAMED

WILLIAM OAKLAND

WHO DIED JUNE 27th 1887

AGED 73 YEARS

IN THE MIDST OF LIFE WE ARE IN DEATH

Like the other memorials so far described, the next one concerns a family that has been written about in earlier numbers of Sneinton Magazine. Also situated close to the Forest Road railings, it is one that I mention with mixed feelings, the history of the family commemorated having given me severe headaches in the past.

THE WRIGHT MEMORIAL, with the corner of Addison Street in the background.

THE WRIGHT MEMORIAL, with the corner of Addison Street in the background.Opposite the end of Addison Street stands a tall pedestal topped by a draped urn. This is in memory of Christopher Norton Wright, who, as it happened, died in that street in 1875. Bookseller, printer, and stationer established for years on Long Row, Wright is remembered today chiefly as the publisher of 19th century directories of Nottingham and Nottinghamshire. Wright's four wives are also commemorated on tablets around the plinth, though only the last of these, Anne, is buried in the Church Cemetery. The first three, Mary Ann, Diana, and (very confusingly) another Mary Ann, are, surprisingly, all buried in Sneinton churchyard, and remembered on a slate headstone a few yards from George Green's grave. The interment of these ladies at Sneinton exemplifies the desire of a townsman to bury loved relations in what were then still countrified surroundings, rather than in a town centre churchyard crowded in by buildings.

This gravestone has cropped up several times in Sneinton Magazine, mainly on account of the sad circumstances surrounding the death of the first wife, Mary Ann. She, poor girl, was married on 16 November 1813, at St Peter's in Nottingham, but died two days afterwards. The two local weekly newspapers gave rather different accounts of the cause of her death. The Nottingham Review reported that '...we have received the affecting intelligence of the death of Mrs Wright, occasioned by taking cold on the day of her marriage, which brought about an inflammation, and last night terminated her mortal existence.' The Nottingham Journal, however, included slightly more detail: 'Last night, of an inflammation in her bowels, Mrs Wright, wife of Mr C. Wright, bookseller, an awful example of the mutability of human enjoyment, having been married only on Tuesday morning last!' It seems likely that Mrs Wright died of appendicitis.

Wright's autobiography, No Hero, I Confess , published almost a century after his death, gives the most muddled and contradictory account imaginable of his life and family.4 Space does not allow further dissection of it here, but, for what it is worth, this woefully misleading book can be found in Nottingham Local Studies Library.

Meanwhile, the Wrights offer two memorials for us to appreciate. The slate stone at Sneinton appears modest when compared to the urban formality of the one in the Church Cemetery; in their contrast, however, they exemplify the developing fortunes of this Nottingham family.

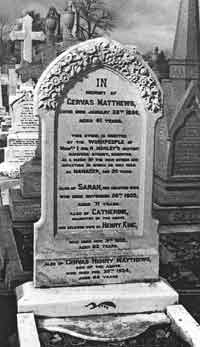

THE HEADSTONE OF GERVAS MATTHEWS and family.

THE HEADSTONE OF GERVAS MATTHEWS and family.There is indeed, to adapt the phrase from the Journal, nothing like a burial ground for bringing home to the onlooker the mutability of human enjoyment. Not yet sated, however, we move from the Wright memorial to the middle of the Church Cemetery, over towards the Forest boundary. Here stands a remarkable tribute to a man who did not live in Sneinton, but worked here. Among epitaphs to several family members are these words, in black lettering on a white stone with a carved garland at its head:

IN

MEMORY OF

GERVAS MATTHEWS

WHO DIED JANUARY 28TH 1896, AGED 61 YEARS.

THIS STONE IS ERECTED BY THE WORKPEOPLE

OF MESSRS. I AND R. MORLEY'S FACTORY

MANVERS STREET, SNEINTON

AS A MARK OF THE HIGH ESTEEM AND AFFECTION

IN WHICH HE WAS HELD

AS MANAGER. FOR 26 YEARS.

In today's climate of relations between management and workers, when job insecurity and workplace bullying are too often heard of, such a heartfelt message seems almost Utopian.

Matthews lived over the Trent from Sneinton, at 'Queen's Elms', 17 West Bridgford Road (now Bridgford Road). At that date West Bridgford would have still been a pleasantly rural retreat, though growing rapidly. Gervas Matthews was himself part of the influx of new residents; like other successful men who worked in Sneinton, his changes of address reflect his rising affluence. At the beginning of the 1880s he lived in St Ann’s Well Road, then moved for a short period to the Trent Bridge end of Arkwright Street, before taking that distinct step up in status by crossing the river.

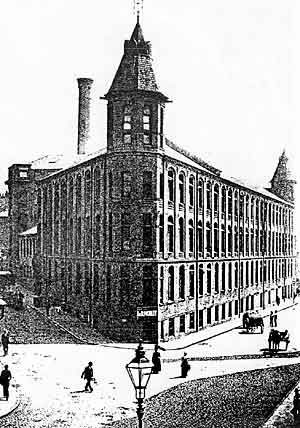

THE MANVERS STREET FACTORY OF I & R MORLEY, where Matthews was manager. It still exists, though much reduced in height, as a result of air raid damage in 1941.

THE MANVERS STREET FACTORY OF I & R MORLEY, where Matthews was manager. It still exists, though much reduced in height, as a result of air raid damage in 1941.Gervas Matthews's service at Morley’s went back far enough for him to have witnessed the devastation caused by the disastrous blaze of 22 August 1874, which wrecked the huge factory at the corner of Manvers Street and Newark Street. This was the costliest fire to have occurred, to that date, in the history of Nottingham. The damage was reckoned at £100,000 - over five million pounds in today's values. People as far away as Radford heard the sound of the factory crashing to the ground as walls and roof collapsed.

(Part two of this article will follow in the next magazine, with accounts of further Church Cemetery memorials associated with Sneinton. These will feature two leading businessmen, a clergyman, and a soldier.)

1. Mary Cannell's George Green, Mathematician and Physicist (1993) is an indispensable account of Green and his life, doing eloquent justice to Clara's mother, the remarkable Jane Green. I gladly pay tribute to this book, and acknowledge my indebtedness to it.

2. A fuller study of John Newton's life and work may be found in Sneinton Magazine 16, 1985, under the title A Talent for Harmony

3. Sneinton's Other Miller, by Tony Shaw, is an informative account of Oakland and his mills. It appeared in Sneinton Magazine 62, 1996/97.

4 See Sneinton Magazine 20 & 21, for an attempt at sorting out this tangle: Tales from St Stephen's Churchyard - 1. C.N. Wright and His Family. A most authoritative note on Christopher Norton Wright of Wright's Directories appears in the April 1999 Nottinghamshire Family History Society Newsletter. The result of many years of research, it is by Mrs J.B. Sampson, a descendant of C.N. Wright's brother.

< Previous