< Previous

MEN ABOUT TOWN:

Further sidelights on local street names

By Stephen Best

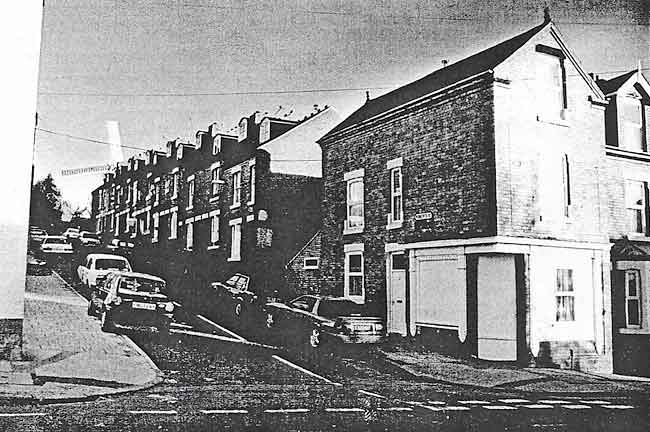

ROBERTS STREET in 1999. (Photo: Gilbert Clarke)

ROBERTS STREET in 1999. (Photo: Gilbert Clarke)IN THE NOTTINGHAMSHIRE GUARDIAN of 24 November 1917 appeared a brief item under the heading: 'Half Named Nottingham Streets.' It reported that 'an esteemed correspondent' had written to the paper, mentioning two local streets whose mode of naming could not, as he put it, easily be accounted for.

This contributor wondered why Lord Street and Roberts Street, off Windmill Lane in Sneinton, had been obliged to share the name of that notable soldier, and why one of these streets could not have been called Lord Roberts Street, and the other something entirely different? He cited the nearby Baden-Powell Road and Port Arthur Road as examples of Sneinton thoroughfares which he considered more euphonious than the 'split' Lord and Roberts Streets. It is rather surprising that he failed also to mention the nearby Lord Nelson Street, which was a perfect example of the sort of name he preferred.

Lord Street and Roberts Street were built in the first decade of the twentieth century, and the earliest census returns for them will not be open to public scrutiny until 2011. For the time being, therefore, we know little about the people who lived in these streets when they were new; electoral rolls give names of voters, but no details of their occupations. The street directories are of limited help, too; until the Second World War, only those people running their own business were included in directory entries for ordinary suburban streets like these, and just two such traders made a token appearance in them. In 1908, John Hodgkinson of 25 Roberts Street was listed as a waste dealer, with a business at 4 St Ann's Well Road. Between the wars Arthur John Murfet lived at 26 Roberts Street; he was a machinery merchant, whose work premises were close by, at the 'LMS Depot, Newark Street' By 1950, when the directory got around to including the names of all residents, it had unhappily ceased to show their occupations.

FIELD MARSHAL Lord Roberts of Kandahar.

FIELD MARSHAL Lord Roberts of Kandahar.Nowadays there must be residents of the two streets who are unaware of the origin of their names, but when the houses were first occupied, about 1904, any explanation would have been totally superfluous. Frederick Sleigh Roberts, who so contentiously occupied two street names, was an outstanding personality of the Victorian high noon of Empire. Born in India in 1832, the son of an officer who rose to be a general, he was from boyhood destined for the Army. During the Indian Mutiny he won the Victoria Cross, and as a major-general in the Afghan War of 1878- 79, set out with 10,000 troops on a famous three-week march of over 300 miles to relieve Kandahar. Knighted, and later given a peerage, Roberts became commander-in- chief in India, and afterwards in Ireland. Now a field-marshal, he was sent out to South Africa at the age of 67 to head the British forces in the 2nd Boer War, after the Army had suffered a number of setbacks in 1899. In one of the defeats that led to his being given this command, Roberts's only son had been killed, gaining a posthumous VC for his bravery.

Created an earl on his return home, 'Bobs’ became the last man to be appointed commander-in-chief of the British Army. After retirement in 1904 he remained a popular public figure, and died of pneumonia in 1914 while visiting Indian troops in the trenches in France. Physically a small man, his ruddy face, with drooping white moustache and little imperial, was familiar on innumerable commemorative plates, mugs, posters, and other tokens of patriotic sentiment. Despite his great rivalry with another soldier, Sir Garnet Wolseley, contemporary reports suggest that Roberts was loved for his genuine modesty. It is good to be able to report that the pub in Broad Street named after him has not yet fallen victim to the craze for renaming licensed premises.1

Returning to the streets themselves, the Guardian's 'esteemed correspondent' judged that the names Lord Street and Roberts Street created a far worse effect than what he termed the the 'similarly sundered' Wat Street and Tyler Street. Although he described them as being in another part of the town, this latter pair of streets was in fact situated in the Meadow Platts district on the fringe of Sneinton, one on either side of Colwick Street (now Brook Street). They lay just behind Victoria Baths, a few yards from Sneinton Market. in one of Nottingham’s most notorious tracts of slum housing. Both streets were pulled down between the wars, Tyler Street going a few years earlier than its counterpart. Every home in the short Wat Street was a back- to-back, each with only one outside wall, but Tyler Street contained, in addition to a number of back-to-back houses, one of the few terraces of better dwellings in the Meadow Platts. These had access to the open air at front and rear. The whole neighbourhood had been identified as ripe for compulsory purchase long before its eventual demolition. As the Colwick Street Area No. 2 Order put it: 'the dwellinghouses in that area are by reason of disrepair or sanitary defects unfit for human habitation, or are by reason of their bad arrangement or the narrowness or bad arrangement of the streets, dangerous or injurious to the health of the inhabitants of the area ...'

Although Tyler Street was in existence at the close of the eighteenth century, Wat Street was not built until more than twenty years later. Indeed, the Beck stream flowed in the open at the end of Tyler Street until culverted as a sewer in the 1820s, when Colwick Street (the Sneinton end of Brook Street) was constructed above it. This interval in time suggests that they were possibly not originally intended to be a pair of 'half-named streets.'

It did not take long for the housing in the neighbourhood to acquire a bad name. This area on the eastern fringe of Nottingham had been pleasant open ground until about 1780, when John Sherwin sold off plots on part of it, the Cherry Orchard or Cherry Garden, to builders in the town. According to William Stretton of Lenton Priory, who was a young man at that time, 'This comprised all that Track of Land from the Beck Lane Eastward to the Old Pottery, & from the Old Glass Houses (Paravicini's Row) to Snenton & from Coalpit Lane to the extent of the Fields.' 2

Sherwin's land was sold at about 5s. a square yard, and others followed in making their orchards and closes available for building. With the Corporation refusing to enclose the open fields around the town and so make possible a sensible and orderly expansion of Nottingham, the 1790s saw land values rise steeply, and speculative builders crammed as many homes as they could into whatever land was obtainable. Robert Mellors wrote that all that was eventually left of these pleasant gardens and orchards, here, and on the southern fringes of Nottingham, was their names, incorporated into streets full of 'houses of the worst description,' such as Cherry Street, Plum Street, Pear Street, and Currant Street.3

The Meadow Platts was one of the parts of Nottingham to suffer a serious outbreak of cholera in 1832, and, as part of Byron Ward in the 1840s, it contributed to the shameful statistics of this, the most unhealthy of Nottingham's seven wards. Average expectation of life in Byron was 18.1 years, as compared with 22.3 in the whole of Nottingham, and about 29 years in the country as a whole. 44.5% of children in this ward died before reaching their fourth birthday. The Beck sewer quickly demonstrated its inadequacy, it being reported that 'The sewer formed on the course of the River Beck is even now incapable of conveying the waters of heavy rains, and has therefore occasioned the houses in its vicinity to suffer from inundation where these have occurred.'4

Three years later the Sanitary Committee painted an even more horrifying picture: 'There are a number of Houses in the Town which have no privies at all attached to them; this is particularly the case in Brook Street and Fyne Street, in which there are thirty-eight houses without dusthole or Privy. In the midst of the most closely built neighbourhoods are filthy Pigstyes, Slaughterhouses, accumulations of Blood and refuse and cesspools all sending out noxious effluvia.’ 5

Thanks to some remarkable and energetic engineers like Thomas Hawksley, and devoted medical officers of health such as Edward Seaton, the town learned much about hygiene and housing during subsequent decades, though there were never sufficient resources available to put right all the ills. In the light of all this, the 1851 census for Wat and Tyler Streets is of great interest, providing a glimpse of the people living there at a time of such appallingly low life expectancy. It shows that thirteen houses in Wat Street were inhabited, with an average number of six occupants. No fewer than nine heads of families were framework knitters, while others earned a living as dressmaker, engineer, or silk glove maker.

TYLER STREET in 1913, showing some of its better houses. WAT STREET rises beyond the line of washing in the distance. (Photo courtesy of Nottingham Local Studies Library)

TYLER STREET in 1913, showing some of its better houses. WAT STREET rises beyond the line of washing in the distance. (Photo courtesy of Nottingham Local Studies Library)Poky though these houses were, some of them accommodated an inordinate number of human beings. No. 14. for example, was occupied by two families. The first comprised a framework knitter named William Morley, his washerwoman wife, and their three children; the second family was that of Henry Bolton (also a framework knitter), his wife, and their two infants. No other house in the street equalled this total of nine occupants, though two had eight. At no. 7 lived Elizabeth Bolton, a widowed hosiery seamer aged 40, her five children, a grandchild, and a lodger - was Elizabeth perhaps a relation-in-law of Henry Bolton? Stephen Carrier, a framework knitter and his wife, shared their home at 15 Wat Street with no fewer than six 'visitors' on the night of the census.

The same returns show 28 inhabited houses in Tyler Street, with a total of 196 residents between them. Heads of families were again predominantly framework knitters, of whom there were seventeen, while others worked as tailor, lace dresser, house painter, chimney sweep, and chair maker. Sub-letting of homes was even more marked than in Wat Street, and one house had as many as thirteen occupants. This was no. 4, where Thomas Smith, a labourer, lived with his wife and four children under the age of eleven; they also had two lodgers, one the infant child of the other. Elsewhere in the house lived the family of a framework knitter named Thomas Bentley; consisting of his wife (a hosiery seamer,) and three daughters, one of them a twelveyear-old working as a confectioner.

No. 18 Tyler Street ran this total close, with twelve inhabitants. George Walker, yet another framework knitter, lived here with his wife, three children, and a lodger. In the same house dwelt a widowed labourer, and the family of Sarah Terry, a seamer, who had three children, and also found room for a lodger. One feels that the depths of drudgery must have been plumbed a few doors away by Mary Green, an unmarried charwoman aged 28, whose nine-year-old son worked in a factory. More fortunate was John Gearey, a framework knitter, and 'master of four men'. His wife was a silk winder, and they and their two small children shared their home with only two other people.

When one considers the meagre sanitary provisions of the dwellings in Wat Street and Tyler Street, it is astonishing that anyone there reached a healthy maturity. The census returns provide further hints of unimaginable hardship. In Wat Street we find a child of seven employed as a 'nurse girl', and a lad of nine as a cotton winder. A high proportion of the inhabitants of these streets were natives of Nottingham and the surrounding area, though one or two had travelled a long way to live in these insalubrious surroundings. The son-in-law of George Hickling at 5 Tyler Street came from America, while Mrs Bullock, of no. 8, had been born in Switzerland.

Having given a brief account of Lord Roberts’ career, we do the same for Wat Tyler, though it is no easy task. Wat (or Walter) Tyler's life could hardly have been a greater contrast to that of Lord Roberts. Nothing is recorded of him before his brief week or two of fame during the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381, and we have no idea what he looked like. A tiler, (his surname is unknown), probably from Essex, he was chosen to be spokesman for the peasants after a mob of several thousand had captured Rochester Castle. With him at their head they seized Canterbury with considerable violence, and marched on London, where more killing and damage took place. At Mile End the leaders of the Revolt met King Richard II, then a boy of fourteen. There they demanded an end to serfdom and feudal services: freedom of labour and trade: and an amnesty for all the insurgents. Further violence erupted again soon afterwards, and a number of people were murdered by the rebels.

What exactly happened at a subsequent conference with the King at Smithfield is disputed. Richard offered the peasants some concessions, but tempers flared, and Wat Tyler was killed by William Walworth, mayor of London. Another version of events has it that the wounded Tyler was taken to St Bartholomew's Hospital, but that Walworth, on learning of this, had him forcibly dragged out and beheaded. The Revolt, whose immediate cause had been the imposition of a hated Poll Tax, soon spluttered to a halt. Some of the other ringleaders were executed, though many insurgents were mildly dealt with. Parliament soon revoked any concessions granted by the king, and the Peasants' Revolt gained no immediately palpable results for the people. It did, however, probably make future governments think twice over such matters as taxation.

Although it seems that Wat and Tyler Streets may not have been originally intended as a name-pair, it would nevertheless be interesting to learn who did choose the name of such a turbulent figure for these two streets. One cannot help feeling that some who had to live in them during the worst conditions of the 19th century might have identified closely with the leader of the Peasants' Revolt, who, though perhaps more a mob-leader than a champion of freedom, could be seen as a dramatic, if vain, representative of the deprived and downtrodden. None of the other streets in this area commemorated anyone remotely as seditious as Wat Tyler.

The sites of both streets can be pinpointed quite easily. Sneinton House, the Nottingham Corporation hostel for working men, was built in 1932 in Boston Street, on the site of Tyler Street, to the designs of Edward Phillips, City Housing Architect, and his deputy Collis Atkin Pilkington. Providing accommodation for 280 men, it cost £32,000, and another £2,000 for furniture. At its opening Sneinton House offered a single night's lodging for one shilling, while a week's accommodation cost 6s 6d. Its management having been taken over by the Salvation Army in the 1970s, the building was, after much discussion, pulled down in the early 1990s, and a less overwhelming successor, capable of housing seventy homeless men, opened on the same spot in 1994. Just across the road, examples of 1930s Nottingham council housing in Brook Street and Bedford Row stand where once Wat Street's dreadful back-to-back houses were squeezed together.

In raising the matter of 'half-named streets' like these, the Nottinghamshire Guardian commented that both pairs dated from 'an age less enlightened in municipal matters'. It is true that Wat Street and Tyler Street were survivals from a much earlier period of Nottingham's development, having been there for over eighty years and over a century respectively. As we know, however, Lord Street and Roberts Street were laid out during the reign of Edward VII, and so been occupied for little more than a decade before the newspaper article appeared. The newspaper must have been indulging in a bit of press hyperbole in lumping these two examples together as representing an earlier dark age of civic ineptitude in naming streets.

Another similar instance of 'split' naming almost certainly survived on the edge of Sneinton in 1917. Although much of the condemned Carter Gate Unhealthy Area, (the block now bounded by Southwell Road, Manvers Street, Pennyfoot Street, and Lower Parliament Street) had become empty just before the Great War, little demolition work was carried out in the locality before 1920. It is, therefore, most likely that Earl Street and its neighbour Stanhope Street still remained here in forlorn dilapidation. Built at the very end of the eighteenth century, this pair of streets perpetuated the name of a remarkable man who caused a sensation in the 1790s when in the House of Lords he supported the aims of the French Revolution, and advocated making peace with Napoleon. So Charles, 3rd Earl Stanhope (1753-1816), became known as 'a minority of one,' in spite of being the brother-in-law of William Pitt the Younger. A notable scientist, Stanhope devised calculating machines, printing presses, a stereotyping process, and a microscope lens. Other experiments carried out by him resulted in 1779 in the publication of his Principles of Electricity.

Stanhope Street was the last old street name from the Carter Gate area to survive after the City Transport bus depot was built, and the street remains as the vehicle entrance to the depot, opposite the new Ice Arena. It is, however, not quite on the same line as the original Stanhope Street, which lay some yards to the north of its successor.6

The Nottinghamshire Guardian's short item ended by wondering whether Nottingham possessed any more examples of street names 'divided' in the manner of Lord Street and Roberts Street. A little reflection, and a careful inspection of the street map, should indeed have enabled alert readers of our 1917 newspaper to identify one or two others not yet mentioned. We must, however, move away from Sneinton to find them.

Pre-eminent among these were two pairs of streets close to the centre of the city. Still in existence, they were originally built at the middle of the nineteenth century, and it is odd that the newspaper correspondent had not spotted them. One of them echoes the theme of Wat and Tyler Streets. Like Wat Tyler, Oliver Cromwell was a dominant figure in an English revolution, though an infinitely more important and successful one. As is well known, Cromwell Street runs up from Waverley Street, to Alfreton Road, along the boundary of the General Cemetery. A side turning off Cromwell Street is Oliver Street, which leads to a pair of streets commemorating yet another restless spirit of an earlier age. Parallel to Cromwell Street lies Raleigh Street, off which runs Walter Street. After more than 130 years Nottingham has become well accustomed to these four perfectly good street names. It is undeniable, however, that Oliver Cromwell Street and Walter Raleigh Street would have had a fine ring to them.

Moving rather further afield, another example, not quite fitting this pattern, can be found. This occurs to me immediately, as it is the street in which I grew up. Ewart Road, in Forest Fields, runs south off Gladstone Street, but one looks in vain for a nearby William Street to complete the name of William Ewart Gladstone, the great Liberal prime minister, and one of the most familiar faces of the Victorian period. At the time that Forest Fields (then known as 'Forest Ville') was begun, a William Street did exist elsewhere in Nottingham, off York Street. This was, however, swept away in the 1890s during the construction of Victoria Station, and by the time that Ewart Road was built, there was nothing to prevent a new William Street or Road accompanying it. The omission, therefore, is not easily explained.

This was, however, not a case when one street name would have easily accommodated the full name concerned. Despite what some present-day journalists and broadcasters say, Gladstone was never known as 'William Gladstone' by his contemporaries; always William Ewart Gladstone or W. E. Gladstone, and neither of these combinations sounds very comfortable with 'Street' tacked on to the end. Thomas Isaac Birkin, the Nottingham lace manufacturer and owner of the land on which the streets were built, was also President of Nottinghamshire Liberal Association, so we do not have far to seek for the influence behind the naming of Ewart Road and Gladstone Street.7

While Gladstone's first name is missing as a street name, another man is represented on the Nottingham street plan by both of his Christian names, but not his surname. This is the only such instance I can offer, and to visit it we need travel just a short distance from Forest Fields. Here is no commemoration of a national figure, but an interesting, and largely unrecognized, street-naming after a local man.

HERBERT MAYO LEMAN as a young man.

HERBERT MAYO LEMAN as a young man.A number of streets in and around Nottingham are called after the children of landowners or builders. There are several in West Bridgford, while Russell, Stanley, and Leslie Roads in Forest Fields were named for the children of the aforesaid T.I. Birkin.8 Herbert Road and Mayo Road, however, embody the names, not of two children, but of one of the sons of T.F. Leman of Nottingham.

Thomas Francis Leman was a chartered accountant, estate agent, trustee in bankruptcies, and principal of the Nottingham firm of Leman, Hill, and Hilton. He owned land lying between Sherwood Rise and Hucknall Road, on which he built some houses, and also provided an amenity described by Robert Mellors: 'Bolsover Gardens, a pleasure ground or garden of 1,603 square yards, laid out by the late Mr Thomas Leman for the use and enjoyment of the owners and occupiers of houses on the estate which lies between Nottingham Road and Erskine Street [Road, in fact]. Planted with trees, evergreens and shrubs, it comprises two lawns suitable for the game of croquet. The expense of maintaining it is defrayed by the present owner of the estate and by the several owners of houses on the land referred to, according to area, but it is very small.'9 As part of this little development, towards the end of the 1880s, construction of Herbert and Mayo Roads was begun.

At this date T. F. Leman lived in Hamilton Road, Sherwood Rise. Shortly afterwards he moved to Pelham Crescent in The Park, before settling in his later years at 23 Herbert Road. Here he died in 1919. aged 77. Among family mourners at his funeral at St Andrew’s church was Herbert Mayo Leman. H. M. Leman was born in Nottingham in 1870. and educated at Merchant Taylors' School and Cambridge, where he gained a First in Classics before obtaining a law degree. Returning to Nottingham, he set up in practice as a solicitor just before the turn of the century, his firm eventually becoming the well-known one of H. M. Leman & Leman. He listed his interests as music, literature, and horticulture, and was also a respected antiquarian. Some of the results of his 'scholarly and painstaking’ researches into the early history of Arnold, Daybrook, and Bestwood appeared in the local press, and the editors of The place-names of Nottinghamshire paid tribute to the help he had given them. Herbert Mayo Leman died unmarried in 1951 at the age of 81. Like his father, he eventually became a resident of the pleasant thoroughfare bearing his name, living at 29 Herbert Road.10

In writing about street names, it is only too easy, as the impatient reader will have realized, to be tempted down some byway of fancy, and it is high time that we returned to the Sneinton neighbourhood. Although no further Sneinton examples on the Lord Street and Roberts Street pattern of 'half- named streets’ come to mind, this meander through local names would be incomplete without reference to a man who was commemorated, not in the names of two streets, but in successive names of the same thoroughfare. He has already appeared incidentally in this narrative, in William Stretton’s description of the Cherry Gardens site.

Over the past three hundred years a number of Italians have made their welcome mark in the commercial and cultural world of Nottingham. Some, like the Guggiari and Bregazzi families, made a living here as barometer and mirror makers, or carvers and gilders. Later on, names such as Capocci and Solari became well-known in the field of ice-cream making, and there are plenty of present-day examples. One of the earliest Italians to settle in Nottingham was Count George Paravicini, a potter, who died in 1735 and was buried in St Mary's church, some seven years after his wife Berenice. It is thought that Paravicini arrived in the town towards the end of the 17th century, eventually establishing, or taking over, a glassworks near the foot of Barker Gate. What we now know as Southwell Road was still called Old Glasshouse Street on a map of the mid-19th century.

A century earlier, Badder and Peat's 1744 map of Nottingham showed a street named Paravicini Row joining the lower, eastern, ends of Barker Gate and Woolpack Lane.

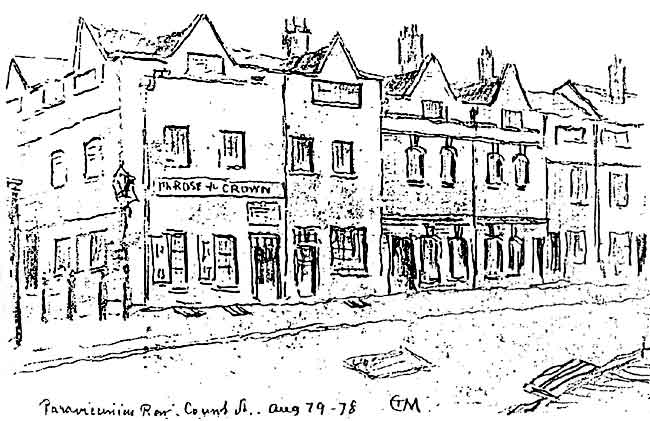

BUILDINGS IN COUNT STREET, formerly Paravicini’s Row, drawn in August 1878 by T C Moore. (Courtesy Nottingham Local Studies Library)

BUILDINGS IN COUNT STREET, formerly Paravicini’s Row, drawn in August 1878 by T C Moore. (Courtesy Nottingham Local Studies Library)Throughout the eighteenth century, however, Nottingham people evidently had difficulty in pronouncing and spelling this name. Palavicini Row was one very minor variation, but in 1768 the Nottingham Borough Chamberlains' records could come no nearer to an accurate written version of it than Palamay Seney Row. It must have come as a relief to all when, around the close of the eighteenth century, the pragmatic townsfolk dispensed with the Count's surname, renaming the street after his title. So Count Street became part of the topography of Nottingham until the 1930s, when redevelopment and road works obliterated it. The site of Paravicini Row/Count Street lies, as we approach the end of the twentieth century, under the emergent Ice Arena complex, across the road from the Sun Valley block, where Pullman's drapery shop used to stand.

The 1851 census returns suggest a rather greater degree of prosperity in Count Street than we found in the nearby Wat and Tyler Streets. At no. 2, for instance, lived Joseph Wells, a 70 year-old sinker-maker (sinkers were components of stocking-frames or knitting-machines.) Also resident in the house were his three married daughters: (lace trimmer, dressmaker, and cap maker,) their husbands (all lacemakers,) and Wells's six granchildren. This grand total of thirteen occupants, seven of whom were in gainful employment, equals the highest of any household in this account. Next door to Wells resided Valentine Sotheran, his wife, and three young daughters; Sotheran was a boot and shoe maker, evidently successful, employing six men.

Elsewhere in Count Street lived James Arnold, another sinker-maker, who had five men working for him, and William Bilbie, a master-carpenter who employed three. At no. 14 was John Cope, aged 45 and a Chelsea pensioner; Cope's household consisted of himself, his wife, and his 'son- in-law': what we should today call his stepson. Perhaps the most interesting entry, however, is that of the Curzon family at nos. 11, 12 and 13. The head of household was John Curzon, a single man of 51, who called himself a 'landed proprietor'; one supposes that he was a landlord, living off his rents. His two brothers, also unmarried, were market gardeners. One of these, George, clearly had a substantial business; he employed six men and three boys, and had 47 acres under cultivation. The spinster sister of these three men lived with them as their housekeeper.

SNEINTON in 1915, showing the locations of (1): Lord Street and Roberts Street; (2): Wat Street and Tyler Street; (3): Count Street.

SNEINTON in 1915, showing the locations of (1): Lord Street and Roberts Street; (2): Wat Street and Tyler Street; (3): Count Street.Sixty years on, at the outset of the Great War, a few businesses were still hanging on in a declining Count Street, including the Meadow Laundry, the Rose and Crown pub, and Solomon Smith, tile fixer. Smith was to survive doggedly there until 1932, when he became Count Street's last ever entry in Nottingham street directories. Although Count Paravicini cannot be claimed as someone whose name occupied the names of two streets, he must be unrivalled in having given his name twice to the same street, simply because locals failed so completely to come to terms with his surname.

It is quite possible that some relevant street names have been overlooked in this ramble, and I shall doubtless hear of any omissions. However eccentric or capricious some of these local names may appear, though, the palm for the ultimate in split street names must go elsewhere. This occurred, not in Sneinton, and indeed not in Nottingham at all. It was to be found in London, mecca for the hunter of inconceivable names. South of the Strand, developers laid out streets on the site of the demolished mansion of the Dukes of Buckingham. So there came to be built an unforgettable trio: Duke Street, Buckingham Street, and (what else?) Of Alley.

1. Imperial Echoes, in Sneinton Magazine 2, Autumn 1981, is a brief note on some Sneinton street names which recall military campaigns and personalities of the British Empire. Among those mentioned are Lord Street and Roberts Street, Baden-Powell Road, and Port Arthur Road

2. The Stretton manuscripts. 1910

3. In and about Nottinghamshire. 1908

4. Thomas Hawksley. Replies to the queries issued by Her Majesty's Commissioners for inquiring into the present state of large towns. 1844

5. Report of the Sanitary Committee to Nottingham Town Council. 13 December 1847

6. An account of the Carter Gate/Manvers Street Unhealthy Area can be found in Unfit for Human Habitation, in Sneinton Magazine 14, Autumn 1984

7. For further absorbing detail see Christopher Weir: The growth of an inner urban housing development: Forest Fields, Nottingham, 1883-1914. Transactions of the Thornton Society 89. 1985

8. C. Weir: op cit.

9. Robert Mellors. The gardens, parks and walks of Nottingham and district 1926

10. H.M. Leman's wide interests are hinted at in his charmingly-drawn personal bookplate. Music is not represented, unless a stained-glass songbird counts, but his other passions are clearly shown. An hourglass, a copy of Horace, and a quill pen in an inkwell, stand upon a carved desk at a library window. In a pleasant garden beyond this is a wheelbarrow with a spade leaning against it.

< Previous