< Previous

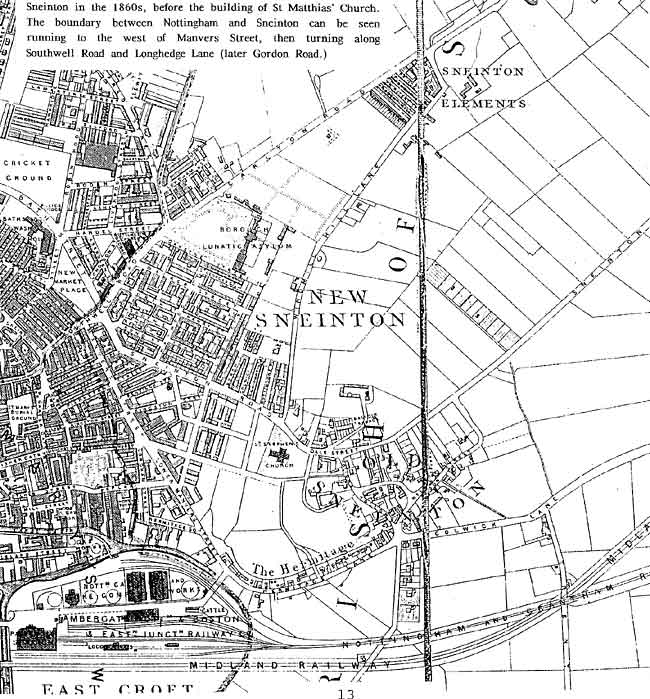

A CHURCH’S YEAR:

Part 2: “A Great Religious Character”:

Victorian Sneinton Through The Eyes of its Parish Magazine

By Stephen Best

(Part 1 of this article related how The Sneinton Parish Magazine came to be set up, and examined its issues for January-August 1869. Part 2 deals with the remaining months of that year, and with Vernon Wollaston Hutton, the vicar who started the Magazine.)

THE SEPTEMBER 1869 NUMBER OF THE Sneinton Parish Magazine reported a successful first Harvest Festival at St Stephen's. Although the season had been unusually late, resulting in the crops being not fully ripe: 'It was kept with great zeal and devotion.' Readers were told of the tasteful arrangements of corn, flowers and fruit that adorned the church, where the Archdeacon of Nottingham preached 'an able and impressive sermon' at the evening service. The offertory provided over £9 towards the improvement of the chancel.

Much space was given to the proposed Church Middle Class School earlier mentioned by the vicar in his parish letter. Hutton noted that the High School was the only 'public school' in or around Nottingham above the rank of a National School, and that it was very difficult for those living outside the borough to find a place there. Parents wanting further education for their sons - daughters, alas, were not mentioned - therefore often had to send them to boarding schools. It was hoped to start a Middle Class Day School in the large room of Sneinton Public Offices in Hermit Street, which was available at a low rent. The school would initially be under the committee of the Church School: that is, the vicar, churchwardens, and two other elected members. According to age, the fees would be 21s or 15s a quarter.

It was expected that of £150 needed for running the school for its first year or eighteen months, £50 would be forthcoming from the National Society, but that the remaining balance would have to be raised locally. Chief among donations already promised were £10 each from Earl Manvers and the vicar. Three men had each subscribed £5; Charles Seely, the new Liberal MP for Nottingham: John Webster, one of the churchwardens: and the Rev. M Atkinson, the first curate appointed by Hutton. Nathan Pratt, the other Sneinton churchwarden, had given £2. 'The school will also be an advantage to the parishes of Carlton and Sneinton,' wrote Hutton. He went on to propound a view of the state of education, with which not everyone would have concurred: 'It is hardly necessary to enlarge upon the vast importance of providing a thoroughly sound and religious education for the middle-classes. At the present time they have less facilities for obtaining this than any other class. The higher classes are amply provided for by the rich foundations of our public schools and universities; the poor can get a first-rate education of its kind at our national schools.'

More cricket was reported, too. On 7 August the Church School had again trounced the hapless Albion School, winning on first innings. The victors could total no more than 64, of which W. Kerry made 26. The Albion, however, replied with a puny 21 all out, the top scorer making only six, and J. Eyre taking seven wickets for the Church School. Another new advertiser made his bow this month, in the form of J.T. Blackwell of Warser Gate, 'Joiner and Undertaker in General;' Blackwell advised readers of his extensive stock of coffins, and of the hearses, mourning carriages, and funeral carriages he had available at all times.

The October magazine found the Rev. Vernon Hutton typically full of vigour and innovative ideas, announcing the opening of a night school for boys. This would be held in the boys' schoolroom, Windmill Lane, for two hours on four evenings each week. Reading, writing, and arithmetic were to be taught to youths aged fourteen and over, who would pay 3d a week for this tuition. Communicants’ classes for young men and women would also get under way during the month. In this issue the vicar addressed his readers through the first of his papers on "The Christian Life'. Religion, he wrote, was not simply a glow of excitement, a sense of peace, or a state of trust. What was required was a life quite given up to God’s service, and obedience to His will. This involved more energy, downright hard work, and perseverance, than it took to become distinguished in learning or successful in business. How this was to be attained would be explained in future papers.

November 1869 saw another heavyweight magazine, with further elucidation of Vernon Hutton’s principles and practices. An additional 7am Holy Communion would be celebrated on all Holy Days, and Litany and Sermon would take place at three o’clock each Sunday throughout Advent. The Rev. Arthur Walker from St Mary's Glasgow was to be a curate at Sneinton in the place of the Rev. John Riley, who had resigned. This, being the first and last we hear of Mr Riley in the magazine, must, sadly, be our hail and farewell to him.

SNEINTON CHURCH SCHOOLS, WINDMILL LANE. A photograph taken shortly before the school moved to new premises in 1968. The windmill car park now occupies the buildings seen here. Photo courtesy of Jim Freebury.

SNEINTON CHURCH SCHOOLS, WINDMILL LANE. A photograph taken shortly before the school moved to new premises in 1968. The windmill car park now occupies the buildings seen here. Photo courtesy of Jim Freebury.The vicar had also drawn up a set of rules 'For the purpose of improving the discipline of the boys of the choir and increasing the regularity of their attendance.' Their white surplices, he explained, were not for mere dignity or beauty, but represented the purity which they should possess for such an office in the church, and imitated the white robes of the saints and angels. There were to be 14 choristers, together with any supernumeraries thought necessary. They were not to be admitted to the choir until having attended practices for at least six weeks, and were then regularly to be at Sunday services, at least two weekday evening services, and practices. Choristers who satisfied these rules would be educated for half the usual fee in the upper division of the Church School, and if they left to take a job, would, until they reached the age of 17, receive financial rewards equal to this school fee allowance. Choristers would be required to observe strict rules of attendance and behaviour.

The Appendix to Hymns Ancient and Modern was to be used at Sneinton services. Nothing, thought the vicar, could be more suitable, as the complete hymn book included eight hymns written by the Bishop of Lincoln.1 A list was given of available editions of A. & M. and its Appendix, and it was hoped that members of the congregation would buy copies. One full edition was on sale for a penny: 'but we recommend our readers to see it before purchasing it as the print will not suit many eyes.'

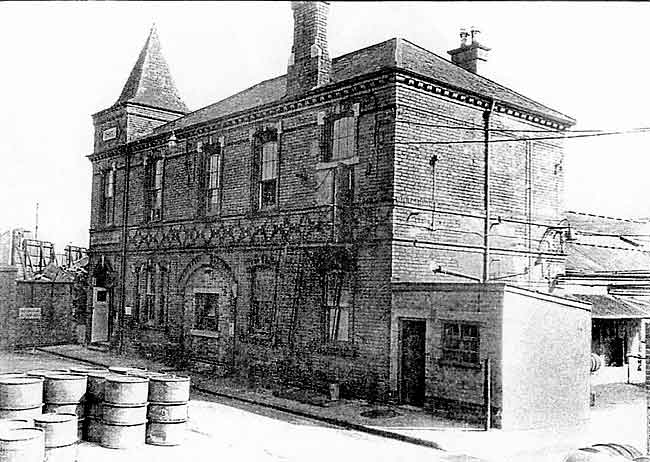

SNEINTON PUBLIC OFFICES, Hermit Street, where the Church Institute was first held. A view dating from 1960, when the building was part of the Boots complex. For 52 years it had housed Sneinton Branch Library and Reading Room.

SNEINTON PUBLIC OFFICES, Hermit Street, where the Church Institute was first held. A view dating from 1960, when the building was part of the Boots complex. For 52 years it had housed Sneinton Branch Library and Reading Room.Sneinton Church Institute was to open on 1 November, in the large room at Sneinton Public Offices. Its president, naturally, was the vicar, with his curates and churchwardens as vice-presidents. John Steedman, of Notintone Place, headmaster of the Church Schools, was treasurer. The aims of the Institute were admirable; to provide instruction and recreation for young men over the age of 15 through a library, reading-room, evening classes, lectures and amusements, for a subscription of sixpence a month. The reading room was to be open every evening except Sunday. Though the officers and committee were all to be communicants of the Church, membership of the Institute was open to everyone. In connection with the hoped-for library, donations of books and back volumes of newspapers and magazines were solicited. It was also intended to form 'a cricket and foot-ball club.' As many local people will remember, the Institute was from 1880 housed in a building in Notintone Street, towards which Mrs Susan Davidson of Sneinton Manor House made a substantial contribution of £3,000. It was destroyed by fire in the 1960s.

Vernon Hutton returned to the matter of his beliefs, and enlarged on a question he had alluded to in his letter to parishioners. This was the place of private Confession in the Church of England. The vicar knew there was some anxiety over his teaching on this subject, and sought to put his views on record. He did not, he said, propose to discuss whether the practice of confession and the power of absolution were scriptural or unscriptural, useful or hurtful, reasonable or unreasonable, moral or immoral. In a long discourse, nowever, he argued that the Prayer Book specifically authorized priests of the Church of England to perform this rite, and that some of his congregation had already voluntarily approached him. For these, and for others, he wrote: 'I propose to remain in the Vestry of the Church every Wednesday evening after the service until half-past nine for the purpose of ministering to them, or of giving advice on this or other subjects.' Hutton recognized that: 'There will be many who will read these words of mine with displeasure.' but urged his critics to examine their own consciences, and ask themselves whether they might be prejudiced in this matter.

In the light of all this, it can have surprised no one that the same page included an announcement of the setting up of a Nottingham branch of the English Church Union. This had been founded in 1860: 'To uphold the Catholic character of the English Church, to resist all attempts to reduce her to the level of a mere Protestant society, and to afford counsel and assistance to all suffering persecution for upholding the doctrine and discipline of the Church as laid down in the Prayer Book.' The chairman of the newly formed Nottingham Branch was the Rev. Vernon Hutton. In inviting men and women to become members, the vicar forecast that the next session of Parliament was likely to see attempts to amend the Prayer Book in essential particulars. The English Church Union, he said, must defeat such moves.

Turning aside from such lofty considerations, the magazine ended on a workaday note with another new advertiser, the last we shall meet in 1869. This was S. Meredith, proprietor of a boot and shoe warehouse at 6 Derby Road. The editor was gaining advertising revenue from well beyond the boundaries of Sneinton.

In reaction, perhaps, to the solemnity and profundity of the November issue, the December magazine was of minimum length, though still high-minded enough. The clergy were anxious to hold 'Cottage Lectures’ for young women who did not attend church, and were looking for rooms measuring at least 15 feet by 12 to accommodate these gatherings. Anyone willing to lend a suitable room for one or two meetings a month would be doing the parish a great favour. Likely locations for cottage lectures were identified as Byron or Colwick Street; John or South Street; Pierrepont or Bentinck Street: Lower Eldon or Beaumont Street; and Old Sneinton. The humble dwellings of New Sneinton had clearly been pinpointed as in most urgent need of the lectures, though there can be no doubt that most of the rooms of adequate size were located in the more spacious and comfortable homes of Old Sneinton. The new curate, Mr Walker, was now living in Short Hill, off Hollow Stone. It is surprising that he had not found suitable accommodation anywhere within the parish.

The recently opened Institute already had fifty members; its reading room was already furnished with books, periodicals, and games, and French and drama classes were planned. Three 'entertainments' had been given, and pronounced highly successful.

The vicar was pleased to report that new altar coverings had been presented to the church, and that the chancel was now thoroughly cleaned. He ended his teachings for the year by enumerating and explaining the Church Seasons. Those seeking further spiritual guidance were recommended to buy for threepence a copy of Vernon Hutton's Reasons for being a High Churchman. This was composed in reply to a pamphlet by 'a Dissenter’ and a sermon by Mr W.K. Vaughan of the Albion Chapel. It is good to find mention at last in the magazine of a clergyman of a different persuasion, even if only in rebuttal of his opinions.

The very last page of the 1869 volume contained news of two forthcoming attractions. First was a concert fixed for 2 December in the Institute room at the Public Offices, under the august patronage of the Lord of the Manor, Earl Manvers, and of his Lordship's tenant at the Manor House, Colonel James Davidson. Songs and pianoforte duets were promised from several local luminaries, including our old acquaintances the Misses Webster and Pratt. The cheapest back seats cost 6d, while a few reserved chairs were available at 2 shillings. One is left wondering about this fine distinction between a seat and a chair. Tickets for this event, in aid of Church improvements, were on sale from a number of Sneinton worthies, with a sort of 'West End' box office at Bell's stationers in Carlton Street.

A function likely to be equally jolly was an end-of-term entertainment by boys of the Church Schools, to be held on the evening they broke up for Christmas. There was no nonsense about long holidays here, as the lads would not be released from lessons until 23 December. They were expected to divert their audience of parents and friends with recitations of some of their school pieces, 'interspersed with songs and glees.' Inevitably, the vicar would take the chair.

Fittingly, there appeared a paragraph headed: 'Ourselves.' In this the first year of Sneinton Parish Magazine was reviewed. Subscribers were thanked for their support, and urged to recommend the magazine to a wider circle of friends. If the circulation were doubled, and more advertisers attracted, it would be possible to improve the magazine, and include more local information. 'We beg, especially, to draw the attention of the Tradesmen of Sneinton and the neighbourhood to the advantages we offer as an advertising medium. The magazine is seen by a very large number of families residing in the parish, and is not thrown away immediately like a daily paper, but is generally preserved for months or years.'

The Rev. Vernon Hutton during his time at Sneinton.

The Rev. Vernon Hutton during his time at Sneinton.Such had been the immediate success of the magazine, readers were told, that several other other parishes in and around Nottingham were thought likely to start similar ones. The printer was willing to bind up the 1869 copies in cloth for one shilling; numbers except February were still available for those readers who had missed them. On this confident note we take our leave of the magazine, saluting the accuracy of the editorial prediction that copies would be preserved and read for years. The 1869 issues, on my desk as I write, have indeed lasted for 130 years, proving a wonderfully revealing peephole into Victorian Sneinton.

Having savoured each number of The Sneinton Parish Magazine for 1869, it is time to pay a little more attention to its founder. The Rev. Vernon Wollaston Hutton was the dominant personality of the magazine's first year, and would remain so throughout the next decade and more. Who was this man who made such an impact on Sneinton?

He was born on Christmas Eve 1841 into a well-connected family at Gate Burton, some five miles south of Gainsborough in Lincolnshire. His grandfather, William Hutton, was owner of the Gate Burton estate, and had built the Hall there. Vernon's father was William's third son, the Rev. Henry Frederick Hutton, who in the year of Vernon's birth had succeeded to the advowson2, and to a share of the manor and estate, of Spridlington, about nine miles north of Lincoln. These were bequeathed to him by the will of a childless cousin. H.F. Hutton was Rector of Spridlington from that year until his death thirty-two years later, in 1873. Vernon was the fifth of ten children of Henry Hutton and his wife Louisa Wollaston, eldest daughter of the Rev. Henry John Wollaston, Rector of Scotter in Lincolnshire. They were an interesting and variously talented brood.

The eldest son, the Rev. Henry Wollaston Hutton, was educated at Rugby, and became incumbent of St Mary Magdalen, Lincoln, and a Minor Canon of Lincoln Cathedral. The second boy, Frederick Wollaston, was commissioned in the 23rd South Wales Fusiliers, and served in the Indian Mutiny, being present at the Relief of Lucknow. Emigrating to New Zealand in 1866, he rose to be Professor of Biology in the University of New Zealand, and curator of the Christchurch Museum. He was elected FRS and FGS. The fourth son, Charles Wollaston, also served in the Army, while the sixth, Francis Wollaston, died at the age of eighteen as an ensign in the Royal North British Fusiliers, from injuries received in trying to put out a fire which destroyed much of Georgetown in Demerara (now Guyana.) The youngest son, Arthur Wollaston, entered the Church, and was eventually Rector of St Mary-le-Bow in the City of London. Gilbert Symonds, the only son not to be given the middle name of Wollaston, lived for only fourteen years. Vernon Hutton also had a euphonious trio of sisters, all younger than himself: Louisa Maria, Lucy Caroline, and Laura Josephine. Laura remained, like Vernon, unmarried, and lived with him for a time at Sneinton Vicarage. She died in 1888, aged 36.

Some idea of the standing of the Hutton family may be gained from the marriages they made; one of Vernon's uncles married into the Holden family of Nuthall Temple, and cousins married, respectively, a daughter of the Earl of Charleville, and a daughter of the Arkwrights of Sutton Scarsdale Hall, Derbyshire. Few friends of the Huttons will have been surprised that Vernon and two of his brothers took Holy Orders. The cloth was something of a family profession, and Hutton's father, grandfather, brother-in-law, and two uncles, were also Church of England clergymen.

Vernon Hutton did not follow his eldest brother to Rugby, but was educated at Bury Grammar School, at Bury St Edmunds in Suffolk3. Proceeding in 1860 to Trinity College, Cambridge, he graduated BA in 1865. He was ordained deacon in the latter year, at Winchester, and priest in 1866. From 1865 to 1868 he was, as we have heard, curate to Robert Gregory at St Mary-the-Less, Lambeth, before coming to Sneinton, his only incumbency.

Hutton's activity at Sneinton was prodigious. Taking a leading part in the Catholic wing of the Church of England, he was tireless in expanding the Church's mission in Sneinton. St Matthias' at Sneinton Elements had been consecrated just before his arrival, but in 1872 he opened a mission room in Eldon Street, which in time led to the building of St Alban's church. In 1880 Hutton paid £1,000 out of his own pocket, and made a further advance of £300, for a house and land in Bond Street, Sneinton; in the following year an iron church, dedicated to St Alban, was built on the site. The distinguished permanent building which today serves a Ukrainian Catholic congregation did not appear until after Hutton's death. In 1882 he was the driving force behind early plans for setting up St Christopher's mission church in a distant part of Sneinton parish, on the canal bank at the London Road end of Meadow Lane.4

Although the Hutton family were landed gentry, and may be assumed to have been comfortably off, there is nothing to suggest that they possessed extreme wealth.

Certainly there is no evidence that Vernon had unlimited money of his own to dispose of; as the fifth son he may well have lacked the opportunities granted to his eldest brother, Henry. Bury Grammar School was less obviously prestigious than Rugby, attended by Henry, or Eton, where his cousin went. For all that he gave freely to Church and charitable causes in Sneinton. When he had been Vicar of Sneinton for ten years, a substantial sum was given to Hutton for his own use; he chose to spend most of it in settling the debts of various parish organisations, and only when these were cleared did he purchase some books for himself.

Vernon Hutton's part in the setting up of Sneinton School Board is especially interesting, and has been described at length elsewhere.5 Suffice it to say here that Hutton was implacably opposed to the setting up of a board in Sneinton, believing that the Church School under his control already offered excellent and adequate educational facilities here. Once the school board became an inevitability, however, he was determined to have a strong say in shaping its policies. Conducting a very robust and successful campaign through the pages of Sneinton Parish Magazine and elsewhere, he topped the elections to Sneinton School Board in November 1875 by a huge margin, in the face of some unpleasant attacks in the Nottingham press from opponents of his kind of Anglicanism.

When the Board School eventually opened in Notintone Street, Vernon Hutton was man enough to admit freely that he had by now quite changed his opinion about the value and necessity of a Board School in Sneinton. He had earlier revealed that the result of the school board election had persuaded him, at a time when he was under great pressure to accept the family living of Spridlington, to remain in Sneinton, and give what help he could during a period of 'crisis in the Education question.' A new parish church had just been built at Spridlington in memory of Hutton's father, who had died a year or two earlier. When Sneinton became part of the Borough of Nottingham in 1877. and its school board ceased to exist, Vernon Hutton sought and gained a seat on the second Nottingham School Board, which he held for three years.

In addition to his educational work, Hutton was an indefatigable writer of devotional and doctrinal pamphlets, some of which have been mentioned in passing. The breadth of his interests and concerns is apparent in their titles The mind of Christ: Education, religious or secular?: Reasons for being a High Churchman: Four metrical litanies: Confession and Absolution: Aids to a new life: The Son of Righteousness - meditations on the early life and ministry of Our Lord and Saviour: 'High Church', what is it?: A help to repentance: The corn of wheat meditations on the later ministry, Passion and Resurrection of Our Lord. This last was edited after Hutton's death by his sister Laura.

Although Vernon Hutton always argued that his changes in Sneinton practice and liturgy were based on obedience to the Prayer Book, he did not avoid clashes with his Bishop, Christopher Wordsworth. There was, for instance, a prolonged correspondence between them over the use of vestments, which ended in Hutton having to give ground, far from willingly. He was, however, made a Prebendary of Lincoln in 1881, and Honorary Canon of the Cathedral. It is worth repeating that throughout Vernon Hutton's incumbency, Sneinton was in the Diocese of Lincoln. Until 1837 it had been under the jurisdiction of York, and in 1884 came within the newly created Diocese of Southwell.

In May 1883 Vernon Hutton became too ill to continue his parochial duties, and his active presence at Sneinton virtually ended from that date. He was obliged to go away in an attempt to recover his health, accompanied for some of the time by Laura, but continued to address his parishioners through the columns of the magazine. In December he wrote from Spridlington to say that he would not be able to resume his duties for another three months, but a letter sent from Aberdeenshire in May 1884 brought the news that he would not be returning to Sneinton. He remained nominally as vicar, however, until Michaelmas. As a farewell testimonial from congregation and parishioners Hutton received a silver kettle, and a set of Encyclopaedia Britannica in an oak case.

The foregoing account of Vernon Hutton's piety, ardour, and earnestness at the age of only 27 may suggest a thin and ascetic-looking cleric. In fact he was, even as a young man, plump of face and figure, and prematurely bald. Sadly, he had not long to live after leaving Sneinton. Latterly resident at South Park, Lincoln, he died in Bournemouth on 21 June 1887, aged only 45. His death occurred in the middle of Queen Victoria's Golden Jubilee celebrations, and announcements in the Nottingham press take some finding. The Nottingham Journal of 24 June, however, included a brief item stating that Hutton had died 'of a lingering illness,' the newspaper, incidentally, adding two years to his age. 'Failing health compelled him to resign the living for a Jess laborious sphere of occupation, but he never regained his health, and died after an illness of several years’ duration.'

It had been announced that a special service of commemoration, with funeral sermon, would take place at St Stephen's on 26 June, but as this clashed with the School Festival, it was decided to hold the service over for a further week. Preaching at Sneinton on the Sunday following Hutton’s death, however, Dean Butler of Lincoln:

'Took occasion to refer to the late canon in sympathetic terms. He said they could not show their sorrow more appropriately than in carrying on the work of education which the deceased gentleman had done not a little to promote. He had set a great example by his holy life, and his book of meditations would be handed down to future generations.'

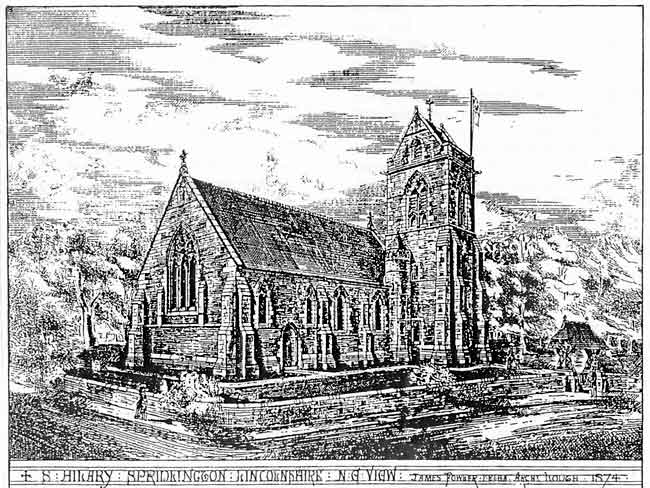

AN ARTIST'S IMPRESSION of SPRIDLINGTON CHURCH in Lincolnshire, built in memory of the Rev. F Hutton. The family gravestones, including that of Vernon Hutton, now stand in a row under the east window.

AN ARTIST'S IMPRESSION of SPRIDLINGTON CHURCH in Lincolnshire, built in memory of the Rev. F Hutton. The family gravestones, including that of Vernon Hutton, now stand in a row under the east window.The Nottingham Guardian further reported that the funeral had taken place on 25 June, near Lincoln, and that St Stephen’s choir had been in attendance. Vernon Hutton had, of course, been buried at Spridlington, at the church built in his father's memory, where he himself might have been rector. Something of a feudal atmosphere still lingers over Spridlington churchyard, where an impressive row of Hutton memorials stretches along the east wall of the church, their superior status unchallenged by those of any other family. Among these Hutton stones are simple crosses in memory of two former occupants of Sneinton Vicarage, Vernon Wollaston and Laura Josephine Hutton.

Something of the enigmatic quality of Vernon Hutton comes through in the funeral sermon preached at Sneinton on 4 July by the Rev. James Weston Townroe, Vicar of St Peter-at-Gowts, Lincoln, and a former curate of Hutton's. Townroe was one of a formidable list of men who had been assistant clergy at St Stephen's under Hutton, and who afterwards rose to distinction in the Church of England. Expounding the late vicar's virtues, Townroe told the congregation that: 'He was a great religious character. This they were all assured of, but they only partially understood it. He was an attractive preacher, his strange reserve and saintliness being the cause of such attraction...Perhaps he was not less remarkable for the courage of his opinions, which the least careful observer must have noted in his character... He never flattered, he never told them he was glad to see what he was not, and he never spoke a word of praise unless he meant it.

The Journal went on to report Mr Townroe’s praise for Hutton's works in Sneinton. 'First and foremost among them were the many wisely-formed and lovingly- organised guilds and associations for the deepening of spiritual life. Then there was the discreet, restrained, yet earnest and tender care for individual souls, who sought his special guidance in spiritual things.' The preacher went on to commend his great work in providing schools that combined sound religious teaching with the best possible secular education. 'But his greatest work of all was the formation of that home, that atmosphere, that fascination, that enthralling power which Sneinton had for all who came within its range.' Townroe concluded his sermon by paying tribute to Vernon Hutton's legacy of pamphlets, which he hoped would always be read and followed.

Other local newspapers chose to highlight different parts of the address, omitting certain passages, or emphasing other aspects of Hutton's ministry, according to their own preferences and prejudices. The Nottingham Daily Express reported Townroe's eulogy on the late vicar’s 'Singular power of judgment, enabling him always to do the right thing at the right time,’ his brave courage of opinions in putting forward for the first time partly forgotten truths... his freedom from servility to public, opinion, yet having the tenderest consideration for the opinions of individuals.' The paper mentioned that many of the congregation at the service wore mourning. The Nottingham Guardian reproduced other vivid passages from Townroe's sermon. 'He believed that Canon Hutton was truly a father in God. It was not because of his high gifts or position in the world, or his intellectual power, although these things had their weight, but it was because of his truly saintly and religious character, which irresistibly drew them to claim fellowship with it... He was also sincere to a fault. Referring to Canon Hutton's change of opinion in connection with the Sacrament of the Lord's Supper, and other portions of the Christian faith, the preacher believed that they were only the outcome of deep thought, and not due to mere changeableness. He had the mind of a man, while he possessed the heart of a little child.'

Vernon Hutton deserves a longer biography than he can be given here, but it is good to shed at least a little light on a largely-forgotten local figure. Through his magazine, a lively picture of Sneinton Church and parish in 1869 has been handed down to us, and later volumes from Hutton's time as vicar are equally deserving of attention. The Local Studies Library in Angel Row possesses a number of his pamphlets, and they remain a testimony to his zeal and sincerity.

In the Lady Chapel of St Stephen's church is a stained glass window depicting St Paul, in memory of Vernon Hutton, whose year of birth is inscribed incorrectly. The east window of St Alban's and an inscription tablet in Latin on the west wall of that church, also commemorate him. A much more public memorial, however, goes unnoticed by most people. When Nottingham City Council built a new housing development south of Colwick Road in the 1920s, one of its streets was called Hutton Street. Vernon Wollaston Hutton thus became the first Sneinton clergyman whose name was perpetuated in a street name. He was, happily, followed in this respect a few years later by one of his counterparts at St Christopher’s, Colwick Road. Taylor Close, off Sneinton Boulevard, is named for the Rev. John Henry Taylor, incumbent of the latter church from 1911 until 1932. It is a pity that these two never met. They would, no doubt, have found much on which to agree, but certainly much about which they would not have seen eye to eye. Their theological arguments would have been well worth hearing.

I end on a personal note. Through many years of inquiring into Sneinton's modern history, I have come to regard Vernon Hutton as one of its most remarkable and pivotal figures. He was vigorous, clearsighted, determined, and very able indeed. A capable administrator, and a passionate educator, he was eloquent and convincing as a writer, sometimes displaying an unexpected hint of humour. He gave freely of his time, his money, and his strength, and was a devoted minister of the Church. All this I acknowledge, yet something - I cannot define what - makes it hard for me to feel for him the affection that logically seems his due. Respect and admiration are there in plenty, but perhaps one had to know the man personally to like him. Yet the preacher of his funeral sermon hinted at complexities of his personality, which may have distanced him even from his contemporaries. I can only hope that I have done him justice.

1. Christopher Wordsworth, Bishop of Lincoln from 1869. Nephew of the poet, he was formerly headmaster of Harrow.

2. The right of presentation of a clergyman to a vacant benefice.

3. The Wollaston side of the family had strong Suffolk connections, and Vernon Hutton’s great-uncle had been MP for Ipswich. William Hyde Wollaston, a distinguished scientist and physician, and cousin of Vernon's grandfather, began in medical practice at Bury St Edmunds.

4. See: 'Mission accomplished: the early years of St Christopher’s church': Sneinton Magazine 49, Winter 1993/94.

5. See: 'A bed of nettles: the brief, eventful life of Sneinlon School Board’: Sneinlon Magazine 50-51, Spring-Summer 1994

I wish to thank several good friends. Joyce Hather gave me her 1869 volume of The Sneinton Parish Magazine : Michael Brook, and Malcolm and Mary Stacey, read the manuscript and offered helpful suggestions: George Andrew not only read the draft, but also took me in his car to Spridlington. Any errors are of course my responsibility.

< Previous