< Previous

THE POET and THE PASTOR:

Memorials to two local non-conformists

Part 1. The Methodist: ‘For the good of the local poor’

By Stephen Best

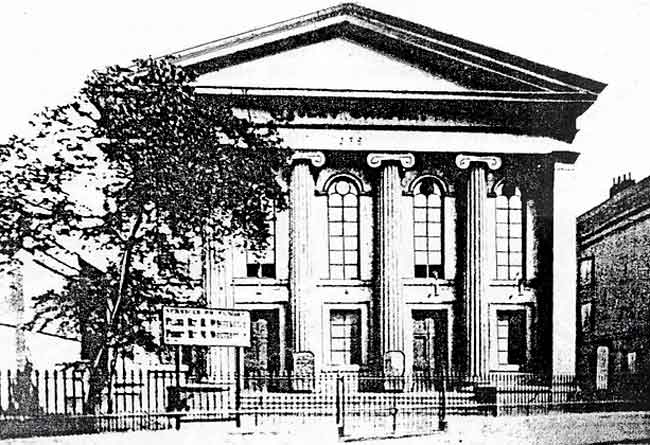

WESLEY CHAPEL, Broad Street (now the Broadway Cinema).

WESLEY CHAPEL, Broad Street (now the Broadway Cinema).MEMORIALS TO PEOPLE with interesting local associations are not only to be in found in Sneinton churchyard. The stories behind several gravestones in the Church Cemetery on Forest Road have been told in Sneinton Magazine,1 and equally rewarding discoveries can be made by exploring Nottingham General Cemetery, which stretches from Canning Circus down to Waverley Street.

This, the older of the town's two great Victorian cemeteries, was opened in 1838. It was situated well away from dwellinghouses, unlike the parish churchyards and burial grounds it replaced, which were often unhealthily crowded in among houses. Nottingham, having suffered a cholera outbreak earlier in the 1830s, was keenly aware of the risks run by the living in having the dead buried too close to them.

Not only that; most of the old churchyards were full, and nonconformists had also taken to interring their dead in the tiny yards surrounding their chapels. This was necessary because many Church of England clergy refused to bury unbaptised people in their churchyards, and nonconformist ministers were prohibited from conducting services on consecrated ground.

It was originally intended that the General Cemetery be entirely unconsecrated; the absence of consecration would allow Methodists, Baptists, Roman Catholics and others to have burial services conducted by ministers of their own denominations. In the event, part of the cemetery was consecrated for Anglican interments, and until their demolition in 1958 the cemetery possessed two separate chapels. Dissenters had a small, but very dignified, Greek Revival building, while the much less impressive Anglican chapel was Gothic. They were pulled down at a time when the cemetery had descended into almost total decay, and serious doubts about its future had arisen.

THE LACE MARKET and SNEINTON in the late 19th century, locations mentioned in this article include:

THE LACE MARKET and SNEINTON in the late 19th century, locations mentioned in this article include:1. Halifax Place Chapel ...2. Wesley Chapel ...3. Byron Street ... 4. Upper Eldon Street ...5. Pump Street ... 6. Sneinton Market ...7. North Street Chapel

[Click on the map for a larger version suitable for printing]

The memorials which claim our attention now are in what is known as the Dissenting part of the General Cemetery, and commemorate two men who contributed much to the nonconformist life of Sneinton and neighbourhood. Their burials, rather oddly, are recorded as Anglican in the cemetery records, though their funerals were conducted by nonconformist ministers. The more recent of the two is still occasionally remembered locally, but the earlier seems to have fallen quite into oblivion. It is his story we tell first.

Henry Hogg was born at Radford on 20 October 1831, just ten days after the Reform rioters had burned down Nottingham Castle. His father Joseph was a hosier, of Park Hill, Derby Road, partner in a business named Horner and Hogg: later Cox, Horner and Hogg.

By the time Henry was in his teens the family business was situated in Wheeler Gate, but soon afterwards it moved the short distance to Mount Street. Here it stayed for many years before transferring to more convenient premises in Upper Talbot Street. Following Joseph Hogg's death in 1850, his widow Elizabeth was a co-partner in the firm with Joseph Thompson Hogg, her elder son, who directed business affairs. Young Henry, however, did not enter the family hosiery concern, and was described in the 1851 census as 'solicitor's general clerk.' At this time all Mrs Hogg's children, two sons and six daughters, were living at home with their mother at Holborn Villas, Talbot Street, where Henry was to spend most of his life. These houses were pulled down towards the close of the nineteenth century to make way for the new Nottingham Corporation power station, and their site now lies somewhere beneath the Royal Moat House Hotel or the adjacent car park.

HENRY HOGG.

HENRY HOGG.In 1858 Henry had his own practice as a solicitor, with an office in Clinton Street. By 1862, however, he had moved to Market Street. This was not the present-day street of that name, but the part of Fletcher Gate between Byard Lane and Weekday Cross. Here Hogg practised law next door to the Crown and Cushion pub and Palace of Varieties. Although this was said to be a respectably run establishment, it is most unlikely that Henry Hogg would have approved of it. After only a few years he relocated his office again, this time to Wheeler Gate.

At the age of 18, Henry Hogg had written a blank verse work titled Mournful Recollections, in which he told of a poet mourning the death of his lady-love, who had succumbed to 'fell consumption.' This poem remained unpublished, but Hogg's first appearance on a wider stage came three years afterwards with the publication of his Poems, a volume of just over 200 pages, published in London and Nottingham.

Like many budding poets of the day, Henry Hogg had by now found inspiration in the works of Tennyson, though one cannot help feeling that his works resembled the master more in feeling and style than in quality. Even allowing for his extreme youth, the opening verse of a serious poem such as The Reconciliation seems capable of evoking more laughter than tears:

'The ancient feud had died between

Our houses, joy was in our halls

And 'neath the elm trees on the green

Were singers, singing madrigals.'

Nor do the first lines of Ellen give many hints of genius:

'Walter loved Ellen, and for many years

Had lived in the same village: now there came

The voice of war and call'd him far away

And months pass'd swiftly, but no tidings brought

Of how he fared, and when he would return. '

Notwithstanding plenty of verses like this, Henry Hogg was highly regarded as a poet. Only a year after the publication of Poems, William Howie Wylie, in his Old and New Nottingham,2 judged that Hogg deserved inclusion in a chapter on local worthies. Describing him as ' a young poet of great promise...' Wylie considered that Poems was 'an unpretending little volume... which, while inheriting many of the blemishes, as well as beauties, of his model Tennyson, still gave token that another man had been born into the world to fulfil the poet's noble mission. All his productions are marked by artistic skill...'

Having a number of poems published in the Christian Miscellany, Hogg also wrote numerous carols and hymns, some of which were set to music. His carols were sung for years at Christmas at Nottingham Wesley School, and articles written by him on Charles Wesley's hymns were printed in the Methodist City Road Magazine.

It is apparent that Henry Hogg was not the only Nottingham poet of his day to idolise Tennyson. The poet's son recorded that in 1855 'an unknown Nottingham artizan ' sent a volume of his poems to Tennyson, and later paid him a visit, requesting Tennyson to read aloud from his poem Maud. A Nottingham newspaper columnist asserted in 1946 that this man had in fact been Hogg, but a young solicitor was unlikely to have been remembered by the Tennysons as an artisan. Nor was Hogg unknown by that time, his work having been already published. We may assume, therefore, that Tennyson's visitor was a Nottingham contemporary of Henry Hogg.

A later volume of Hogg's poems, Songs for the Times, was published in 1856, but soon withdrawn from sale. It was widely held that, had he applied himself to the writing of poetry, Hogg would have attained real distinction. As we shall hear, however, his work as a solicitor, and even more importantly, his ardent and practical Christian faith, occupied him to the exclusion of other activities. His beliefs shone through everything he wrote, and his deep sincerity was what most people remembered him for after his death. Henry Hogg himself was said to have considered his later poems his best literary work, but these were never published, and a volume in preparation at the time of his death never saw the light of day. Lest the short examples of his work quoted above have led the reader to underestimate his poetical gifts, it is only fair to mention that his literary abilities earned him, rather surprisingly, a place in the Dictionary of National Biography.

How, though, did Henry Hogg come to be regarded with such respect and affection in Sneinton? The answer lies in his lifelong devotion to Wesleyan Methodism, and in his love for his fellow-man.

Some years before Hogg's birth, Halifax Place Chapel had decided to begin mission work in the rapidly growing district of New Sneinton. A Sunday School was started, and open-air preaching conducted, with meetings in private houses. Then, in 1825, a small chapel was built for about £400 at the top of Byron Street, off Sneinton Road. After services ceased in 1851, the chapel building was used as a day school for several years.

One Nottingham native who remembered this period vividly was the Rev. Isaac Page, who for half a century served as a Methodist minister. Just before the outbreak of the Great War he set down his boyhood memories of Sunday School at Byron Street.3 'The local brethren used to come and conduct service in the afternoon after school, the scholars, of course, remaining, a few persons beside them making up the congregation. Dry sermons they were to most of us. One Sunday, when the collection was made, a solitary penny lay on the plate, the total sum of the worshippers' offering.' Mr Page also recalled 'a long procession of Sunday scholars from Byron Street moving along Hockley to the morning service at Wesley.'

'Wesley' here refers to the Wesleyan Chapel in Broad Street, opened in 1839, and now the Broadway Cinema. This building has the strongest of Sneinton associations, being the scene of William Booth's conversion in 1844 to a life as a Christian missionary. Henry Hogg was a regular attender here, and a teacher in the Sunday school and weekday evening schools. So well attended was Wesley Chapel that in 1863 its Sunday School numbered over 1100 children and 157 teachers.

The Hogg family had long been linked with Methodism, with Henry's grandfather a teacher at Halifax Place Sunday School. When the Methodist Circuit was divided in 1843, Henry and his brother moved to Wesley Chapel, which had become the head of Nottingham North Circuit. Both assumed heavy responsibilities at Wesley Chapel. Henry, then only 24, supervised the Band of Hope there, and two years later he and John became joint superintendents of Wesley School. Henry later added to these duties that of General Secretary.

Nearly all his time and energy came to be spent in Church work, especially in missions towards the poor, and in 1862, he was a leading influence in setting up a mission room on the edge of Sneinton, at Pump Street, in the Meadow Platts, where open air services and meetings in houses had previously been held. This was one of the very poorest parts of Nottingham, lying between Colwick Street and Platt Street, a hundred yards or so from Sneinton Market, and just behind the public baths. Some idea of what life in Pump Street was like can be gained from descriptions of the nearby Parrott's Place, Wat Street, and Tyler Street.4

In 1874 Henry Hogg, by acquiring a room in Upper Eldon Street, compensated for the loss of the Byron Street mission two decades earlier. A Sunday School for 140 children was started in Eldon Street, supported, like the Pump Street mission, by voluntary contributions, until in 1885 the Methodist Conference directed that both should come under the control of a committee. By that time, the Eldon Street premises had clearly become inadequate for their purpose, and a new chapel was built not far away in North Street. Costing £427, it had seating for 300. Always working under difficulties, in what remained a deprived area of Nottingham, it remained open until 1935, afterwards passing into the ownership of the Salvation Army. It disappeared in the late 1950s, under the wholesale redevelopment of the New Sneinton area.

12 PORTLAND VILLAS, Elm Avenue: the last home of Henry Hogg (Photo: Stephen Best)

12 PORTLAND VILLAS, Elm Avenue: the last home of Henry Hogg (Photo: Stephen Best)Sadly, Henry Hogg was never even to see North Street Chapel built. Indeed, hardly had the Eldon Street mission room been inaugurated than he died on 19 June 1874, at the early age of 42. Married only a short while, Hogg and his wife Sarah had set up home in Portland Villas, Elm Avenue. The house, which still stands, must have been a pleasant place to live, with a tree-lined view from its front door providing a sharp contrast to the areas of Nottingham where Hogg did most of his mission work.

Henry Hogg's brief death notice in the Nottingham papers described him simply as 'Solicitor of this town,' but the Nottingham Journal of June’ 29 printed a long and deeply-felt account of the funeral and of the man. 'Anyone passing down Mansfield Road at about half-past eleven last Wednesday morning would have seen a very long funeral procession, extending nearly from the Wesleyan Chapel to the Mechanics' Institute - it made a great shadow in the sunlit streets. Not only did the black clothing of the followers present a sombre appearance, but their faces wore an aspect of gloom.'

The report went on to describe the gathering: the mayor, professional men, manufacturers, tradesmen, youths and young men, Sunday School teachers, and others, and suggested that if anyone who had been impressed by this large attendance had accompanied the cortege to the General Cemetery: 'his anxiety to know something of the departed would have been increased.' Although the two or three thousand present at the burial included people of wealth and position, 'the great mass of people was composed chiefly of the poor. There were working men, fresh from their toil; factory girls; mothers with babies in their arms; and manv infirm old women.'

No one, said the writer, was present merely to satisfy idle curiosity. He had never seen a crowd of people more affected: 'Strong men bowed themselves as though anxious to hide the emotion which would not be controlled, while women and children wept convulsively.'

And why, he asked, were so many present? 'Who, then was this man? ...Who was he whose departure is thus marked by such deep and genuine sorrow? If told that he was Mr Henry Hogg, solicitor, of this town, maybe he who had been interested would not have been much wiser. For this man did not figure prominently in the affairs of this town. His voice was never heard in our Council Chamber; his face was seldom seen upon any of our public platforms; the excited arena of political life presented few attractions for him. He was a man of rich poetic genius, and few were so well versed in the various branches of English literature as he.'

High praise was accorded to Henry Hogg's verses, 'warmly eulogised by the first poets in the land,' and his Christmas and New Year hymns. 'But his devotion to the Muse was too occasional, and thus the laurels which he otherwise might have won in the literary world were withheld. He did not even rise to any marked distinction in his profession. And yet the entire town may well mourn his death. He laboured with a ceaseless activity for the good of the poor of Nottingham. For this work ease and worldly honours were cheerfully sacrificed. Indeed, so much was he absorbed in this work that he was in danger of neglecting the requirements of his business. His heart ached for the destitute and the distressed.'

The tribute to Henry Hogg went on to emphasise the practical nature of his concern for the poor. He had visited the sick, comforted the bereaved, and given money to the needy without ostentation. His Sunday routine had been a punishing one. Early in the morning he would attend prayers at Wesley Chapel, and then take up his duties in the Sunday School. Sometimes he would also preach in Sneinton Market, before returning to the Sunday School for an afternoon session. In the evening, if not in the congregation at Wesley Chapel, he would be preaching at Pump Street, on the fringe of Sneinton, or latterly at Eldon Street, in the heart of it.

'As a friend, they who knew him best can testify that he was most genial and firm. To young men he was most sympathetic and kind. The children loved him.’ The writer concluded with the observation that, if a man's life be measured by his deeds, rather than his years, 'then Henry Hogg, though he died early, lived long.'

This eulogy in the Nottingham Journal is signed J.L., and was possibly the work of Joseph Lowater, a friend and colleague of Henry Hogg at Wesley Chapel. For today's cynical tastes, the account of Henry Hogg may sound too good to be true, but a man whose funeral was attended by over 2,000 mourners must have possessed remarkable personal qualities.

Perhaps the Rev. Isaac Page offers us the most human glimpses of the man. A youthful friend of Hogg in Nottingham, he wrote: 'I see him a fair-haired young man, very gentle in speech, who has already a local reputation as author of two volumes of verse. He is seen in a light boat on the Trent, or on its bank fishing... He speedily became an earnest evangelist, though his temperament, gentle manner and voice, and poetic tendencies seemed to mark him out for work of another kind.'

Page considered that the crown of Henry Hogg's labours had been in and around Sneinton: 'But his great work was in what afterwards became known as the 'Pump Street Mission.' How clearly I see that sidestreet in a poor locality, where every house was just like its neighbour, and the people were neglected, destitute, and irreligious! Henry Hogg first began services in a cottage room, then rented a house, presently taking two, and throwing both lower rooms into one for mission purposes.' Hogg kept the running of the mission in his own hands: 'He used to say that the theological sermons of the regular preachers, local and itinerant, would kill his work!' Isaac Page added an attractive sidelight on Hogg the professional man: 'All this time he was a solicitor in good practice, with offices in one of the main business throughfares. He was the poor people's lawyer, and gave advice, and more, gratis.'

Henry Hogg's portrait shows him to have been a serious-looking man, with a distinct air of the great poet he seemed likely to become. Indeed, his flowing hair, luxuriant beard, and clean-shaven cheeks, remind one of both Tennyson and Charles Dickens. Tiny spectacles of a kind in fashion again today emphasise his gravity.

HENRY HOGG’S GRAVESTONE in Nottingham General Cemetry (Photo: Stephen Best)

HENRY HOGG’S GRAVESTONE in Nottingham General Cemetry (Photo: Stephen Best)Hogg lies buried close to the top path along the Talbot Street boundary of the General Cemetery, about twenty yards from the stone commemorating his fellow-poet, the Sneinton framework-knitter Robert Millhouse.5 Hogg's memorial, an upright brown stone, has a carved rose above the inscription, while its ogee-shaped top is adorned with fussy crockets and an oversized finial. We read that he was a 'Solicitor of this town... He humbly walked with God, and sought with rare disinterestedness and zeal the welfare and Salvation of others.'

The gravestone discloses that Hogg's wife had more than one tragedy to bear in 1874. It has been mentioned that the couple had been married for only a short time, and indeed Mrs Hogg was at the time of Henry's death well-advanced in pregnancy. Below the inscription in memory of Henry Hogg is a sad footnote, recording the death on 1 August of his daughter, touchingly, if oddly, named Ethel Henry. Her birth occurred exactly a week after her father's death, and she was buried in the same grave on 4 August, aged five weeks.

Ethel's burial certificate records that her funeral was conducted by a noteworthy figure, William J. Dawson of Bulwell. Crippled as a child, he became a schoolmaster, learning Greek and Hebrew. A lay preacher before he was 21, he was invited to become a minister. He declined, however, and eventually set up a successful grocery business, remaining a voluntary preacher for 50 years. Dawson promoted the British School at Bulwell, and made a bequest of £400 to his local chapel.

In accordance with his will, Henry Hogg's effects, stated to be 'Under £5,000,' went to his sole executrix, Mrs Sarah Anderson Hogg. She remained at Elm Avenue for a year or two, and then fades from sight, though Isaac Page remembered her as 'Mrs Hogg, of Leeds, well known for her devotion to the interests of Foreign Missions.'

In 1888, just fourteen years after Henry Hogg's death, the editor of the 'Local Notes and Queries' column in the Nottingham Daily Express summed him up in these words: 'Though his poems may not live, yet as a Christian philanthropist , a poet, and a musician, he presents a powerful triple claim upon the love and honour of the inhabitants of Nottingham which will not readily be forgotten.'

More famous men have merited lesser epitaphs.

1 Picturesque and worthy of inspection: Sneinton echoes in the Church Cemetery, Nottingham.. Sneinton Magazine 71-72, Autumn-Winter 1999

2 Nottingham: Job Bradshaw, 'Journal Office', 1853

3 A long pilgrimage, with some guides and fellow travellers. London: Charles Kelley, 1914. Isaac Page's brother Samuel was a very prominent Nottingham tradesman, whose umbrella and luggage shop in Pelham Street was adorned by a statue of Jonas Hanway, inventor of the umbrella.

4 Hardly to be surpassed in misery; Parrott's Place and its times. Sneinton Magazine 53, Winter 1994/5. Men about town: further sidelights on local street names. Sneinton Magazine 73, Winter 1999/2000

5 More about Millhouse can be found in Two Sneinton men of verse. Sneinton Magazine 7, Winter 1982/83

(Part Two of this account will consider a Congregational clergyman who was for many years a pillar of Sneinton.)

< Previous