< Previous

Viewpoint: Cause for concern

By Stephen Best

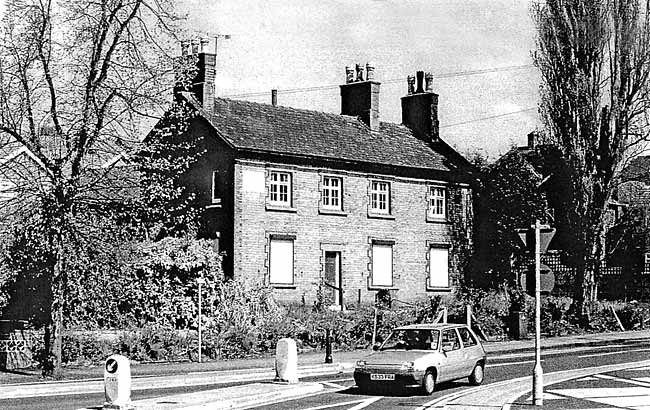

DALE FARM Photograph by Stephen Best.

DALE FARM Photograph by Stephen Best.MY BUS JOURNEY INTO NOTTINGHAM has been a melancholy one over the past couple of years. Not only do the speed bumps along a mile-and-a-half of the route make for an unpleasantly uncomfortable journey, but there has also been the spectacle of two of the most interesting domestic buildings in Sneinton declining into dilapidation, if not ruin. And now the inevitable has occurred in the news that planning permission has been given for the demolition of Dale Farm - Betts's Farm, as it is better known to many local people.

One chooses one’s words with care, but it is hard to escape the conclusion that, as far as the farm is concerned, the writing has been on the wall for several years now. It was widely believed that the building had been bought by a professional man with premises in Sneinton Dale, and that it was the intention to convert the farmhouse if his application to extend his existing premises by purchase and change of use was turned down. In the event the farm was not required for professional purposes, and has been deplorably neglected ever since. Broken windows have been left smashed, letting in untold amounts of damp: the former front garden of the farmhouse became a dump for builder's rubbish: an unsightly loaded skip was left there for a lengthy period, and a most attractive hawthorn hedge cut down.

The man on the Clapham Omnibus was certain that he knew what was afoot: 'That'll never be repaired. Just you watch, the land will be sold and new housing put up.' It seems that the speculation of fellow-passengers was correct. The most surprising aspect of this business was that a building firm erected their signboard on the farmhouse, in the apparent belief that presiding over a decent building of architectural interest while it deteriorated into a nearwreck would be a good advertisement for their professional skills. And, of course, neighbours have had to look at an eyesore all the while.

Profit has apparently been the governing motive once more. One of Sneinton's most characterful old buildings has, to all outward appearances, been bought by someone with no discernable feeling for, or interest in, the face of Sneinton, to be pulled down and replaced when convenient. We should not be surprised if this has been so, as such a course of action seems a perfect reflection of the spirit of the age. One concedes that, judged on a nationwide standard,the farmhouse isn't a great building, and that the removal of a particularly ugly modern outbuilding would greatly improve the appearance of the house. Its local significance, however, is considerable; here is a mid-Victorian building whose demolition represents a grievous loss to us. Dale Farm was certainly good enough for the City Council Planning Department in 1989, when they included it in a booklet entitled Buildings of Sneinton. In a preface which strikes one as ironic today, the Department stated that: 'This booklet highlights buildings which add to the interest and character of Sneinton.' The series, one further reads, 'is designed ... to provide a basis for dealing with buildings at risk from redevelopment or neglect.' Worked really well, hasn't it?

The Sneinton Environmental Society, like any other amenity society faced with a decision like this, will no doubt wish to reflect on how it could have happened, and what course of action they must take if a similar fate threatens any other building which Sneinton just cannot afford to lose. For surely the saving of houses like the Dale Farm is one of the reasons for the Society's existence? The community must learn from the loss of one of the few buildings which reflect the rural history of Sneinton.

The seemingly inescapable fate of the farmhouse may be regarded as an unavoidable consequence - if a disagreeable one - of present day market forces. But what are we to make of the other Sneinton building in a terrible mess? What in God's name, one might ask, (and the expression is not used lightly,) has the Diocese of Southwell been playing at to allow Sneinton Vicarage to fall into such a condition? Glenys Rogerson, in Sneinton Magazine 73 & 77, wrote eloquent 'Viewpoint' articles on this topic, and the Rev. Jean Lamb explained the difficulties in no. 73. Once again, however, the average onlooker, knowing nothing of the background, must be utterly bemused. Listen to people on the bus yet again. 'It's closed down, and the church will be next,' or: 'They want to do away with a vicar here.' What the Church of England has effectively done is to stick a black patch over the eye of Sneinton. Here, at the very heart of the community, is a building passed by numerous visitors on their way to and from the windmill, and what do they see? The place looks blind, and utterly forsaken. Whatever urgent activity has been going on behind the scenes, any casual observer will have come to the conclusion that the authorities do not give a toss about it. Can we really imagine a parsonage in, say, Wollaton or Woodthorpe being allowed to fall into such a state?

Is one being utterly simple in believing that any lodgers should be allowed to remain when an incumbent vacates a vicarage? And while it is no doubt understandable for the authorities to be wary of squatters, surely a short-term let could have been arranged? One has heard, again at third or fourth hand, that the Diocesan view was that enquiries about renting the vicarage had come only from people who were quite 'unsuitable.' One would like to ask how suitable the vandals have been, or the professional thieves who broke in and stole original fireplaces from the building? How suitable is it that a substantial dwelling of the 1830s, mentioned in Pevsner’s Buildings of England series, has been allowed to suffer inevitable damp and decay? How suitable is it that one of the Church's most prominent flagship buildings in Sneinton has taken on the appearance of an irretrievably abandoned dwelling in a scruffy wilderness of a garden? And, most important and pertinent of all, how acceptable is it that the Church could collude, at a time when the scandal of homelessness is properly given a high profile, in a situation which wastes valuable living accommodation over a period of years?

If this short outburst appears intemperate and unfair, I can only reply that on this subject I feel neither temperate nor fair. Lord Byron once attributed to the historian William Mitford the characteristics of 'labour, learning, research, wrath, and partiality.' I regret that on this occasion wrath and partiality have been my foremost emotions.

< Previous