< Previous

IN THE LINE OF DUTY:

Three railway engineers remembered in Sneinton

By Stephen Best

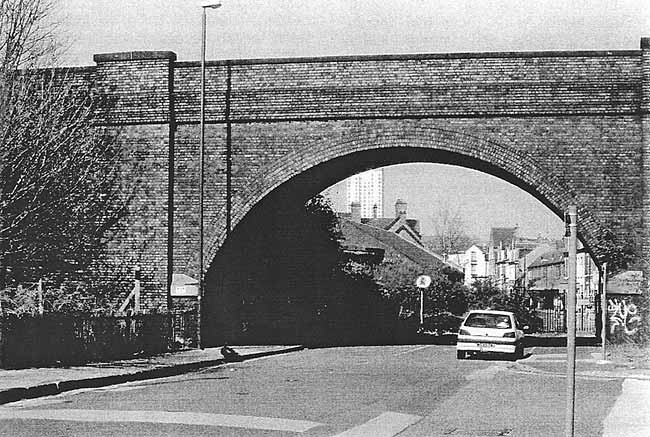

PARRY's surviving masonry bridge on the Nottingham Suburban Railway; Trent Lane, Sneinton. (Photo. Stephen Best.)

PARRY's surviving masonry bridge on the Nottingham Suburban Railway; Trent Lane, Sneinton. (Photo. Stephen Best.)WRITING IN A RECENT ISSUE OF Sneinton Magazine, I commented on the transformation of Sneinton Hermitage and its immediate neighbourhood over the past decade or so. Although recognising that the area was now much cleaner than a generation ago, I suggested that in the process of renewal it had lost much of its distinctive character.

A friend gently disagreed with this view, arguing that the Hermitage, together with the Sneinton end of Meadow Lane, is now a far more pleasant place to live in than formerly, and that most people wholeheartedly welcome the changes. In reply I acknowledged that it was no doubt easy for me to harbour nostalgic memories of a grimly atmospheric locality, without ever having endured any of its less desirable characteristics on a day to day basis as a resident.

Continuing this reflection, I looked up what I wrote years ago about the Hermitage of my boyhood. My most vivid recollection had been of the smell of the neighbourhood, compounded, I had supposed, of Eastcroft Gasworks and the railway yards - Boots factory might also have been mentioned as an ingredient. This characteristic odour, though stirring enough for the boy who experienced it on twice-weekly visits to Sneinton, must indeed have been less tolerable for local householders who put up with it every day.

Among remembered Meadow Lane features had been three little houses called Ambergate Villas, squashed in between high railway embankments and bridges, and just across the street from the railway cattle dock. Once again, while these had caught the eye of a young and impressionable passer-by, they must have been a nightmare to keep clean, and less-than-perfect residences for anyone who did not relish constant reminders of the proximity of the railway. And the railway certainly did impose itself mightily on the atmosphere of Meadow Lane; the street was crossed by four lines within a few yards of each other, with a fifth not far away. Leading off opposite sides of Meadow Lane, the narrow Lindum Grove and Thoresby Avenue were overshadowed on the south side by high embankments, which robbed the houses of much light. All these factors might well have placed the place low on many lists of ideal home locations.

No doubt feeling that he had made his point, my friend turned to the subject of recent street names in the redeveloped Manvers Street/ Hermitage /Meadow Lane area. While approving of two of these - Marham Close and Ardmore Close - he found fault with another new name in the locality. Ivatt Drive, he asserted, means nothing to most people, who are unsure whether it celebrates a place or a person.

Unwilling to give any ground this time, I responded with a favourite soapbox lecture, pointing out that new developments present opportunities for choosing street names that reflect the history of the locality. In this small area of new houses to the south of Sneinton Hermitage, the chance has been only partially grasped. The road names liked by my friend, Marham Close and Ardmore Close, though pleasant enough, have no detectable Sneinton significance at all, and appear to be the result of nothing more than the usual developer's whimsy.

By contrast, two recently laid out roads leading off Meadow Lane - one of them the criticized Ivatt Drive - bear the only names in the new development which give any clue to the past of this part of Sneinton. Although Ivatt Drive and its neighbour Gresley Drive do not commemorate notable Sneinton people, they do perpetuate the memory of the Great Northern Railway, which had a major impact on the landscape of Sneinton for a century and a half. As the last two locomotive engineeers of that railway, Ivatt and Gresley were, among other things, responsible for the design and construction of two generations of railway engines; these, over a period of seventy years or so, crossed and recrossed many thousand times the sites now named after them. As we shall see, they were both very notable men.

Henry Alfred Ivatt - his name rhymed with private - was born in 1851, son of the rector of Coveney in the Isle of Ely. Showing a penchant for engineering, he was at 17 apprenticed by his father at Crewe Works, headquarters of the London & North Western Railway. Here Ivatt shared lodgings for a time with J.A.F. Aspinall, who was to achieve the highest office in the Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway. At Crewe Ivatt worked under two formidable engineers, John Ramsbottom and F. W. Webb. His apprenticeship over, he rose through the ranks from regular fireman to assistant foreman and locomotive superintendent, at Holyhead and Chester respectively, on the LNWR.

Newly married and aged 25, H.A. Ivatt moved to Ireland, to work under his old friend Aspinall on the Great Southern & Western Railway. It is recorded that during that unsettled period of Irish history, when there were still fears of Fenian activity, Ivatt used to keep a loaded revolver in his desk. In 1886, on Aspinall's move back to England, Ivatt became locomotive engineer of the GSWR. There he was responsible for the design of several types of passenger and goods engines.

Although, among enthusiasts of the day, locomotive engineers had what we should now call a high profile, only a minority of railway travellers had any great interest in steam locomotives. Many of them, indeed, would have taken no notice of the engine hauling their train. One of Ivatt’s inventions, however, was to be extremely familiar to passengers, and is still well remembered by anyone of middle age or above who was a regular traveller on the railway thirty or more years ago.

This device was the subject of Ivatt's first patent, brought out in 1888, while he was in Dublin. It was the highly ingenious sprung flap at the bottom of vertically- opening carriage windows, which, with its attached leather strap, was an essential feature in the compartments of the British passenger train.

In 1895 Harry Ivatt was offered the post of locomotive superintendent on the Great Northern Railway, in succession to the aged Patrick Stirling, who had been most reluctant to retire. Stirling’s sudden death caused Ivatt to move from Dublin to Doncaster in something of a hurry, and he took up his new post in March 1896. Originally offered £1750 a year to make the move, he held out for £2500, which must have been some compensation for moving from a beautiful city to a much more workaday town.

Ivatt inherited a stock of good but small locomotives on the GNR, and set about introducing larger and stronger designs. Before doing so he displayed impressive thoroughness by walking the entire length of the main line from King's Cross to Doncaster, then reporting that his examination showed it to be unfit for the bigger engines that would be needed. He told his chairman that, had he known the track was in such a poor state, he would not have taken the job. The chairman replied that necessary track improvements would quickly be carried out: all Ivatt had to do was design the engines.

After building up-to-date shunting and freight engines, Ivatt turned his attention to express types, culminating in the first British 'Atlantic' 4-4-2 locomotive. His second version of this was the celebrated 'Ivatt Atlantic’ class.

The Great Northern in and around Sneinton, however, would see more of Ivatt's goods and mineral engines, and of his mixed-traffic types. It is often forgotten that most of the income of the old railway companies came from mineral and goods traffic, and that comparatively unglamorous engines were those most characteristic of a line. Ivatt's goods engines remained familiar features of the Nottingham railway, many seeing service for more than half a century.

Always a supporter of his footplatemen, Ivatt did what he could to help them carry out their work as smoothly as possible. Not only did he design locomotives with their needs in mind, but argued their case over such matters as signalling rules. Ivatt was also responsible in 1899 for putting forward the plan to build a new erecting and repair shop at Doncaster Works. This was completed in 1901 at a cost of almost £300,000.

An unexpected sidelight on his family life comes with his grandson's recollection that Ivatt would sometimes, with his wife and children, go for a Sunday walk round Doncaster Works. Whether they wore their Sunday best for such potentially grimy excursions is not recorded. When accompanied by his directors on official tours of inspection, he let them wander wherever they wished, and was happy to answer their questions. This was in sharp contrast to his predecessor, who rigidly controlled what directors saw and where they went.

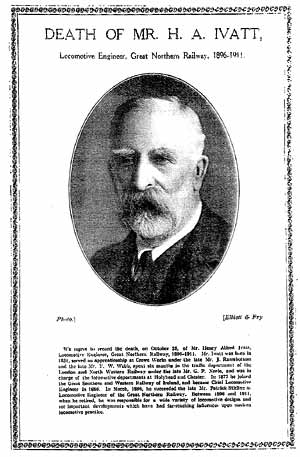

The death notice of H. A. IVATT, from ’The Railway Magazine’ of December 1923.

The death notice of H. A. IVATT, from ’The Railway Magazine’ of December 1923.Ivatt continued to introduce new engines until his retirement at sixty, which he considered a civilized age at which to stand down. He stayed on for a while to assist his successor in taking over, then moved to Sussex, where he spent a pleasant retirement. A Fellow of the Zoological Society, he also enjoyed making ingenious items in wood, and was an enthusiastic amateur magican.

Harry Ivatt died on 25 October 1923, at the age of 72. A tall and rather thin man, he had a prominent nose, and a distinguished full beard and heavy moustache. His voice was described as markedly nasal.

Like other distinguished British locomotive engineers, H.A. Ivatt founded something of a professional dynasty. His son H.G. (George) Ivatt also spent a number of years at Crewe, rising from apprentice to outdoor machinery superintendent. After service in the Great War George Ivatt went to the North Staffordshire Railway, then to the LMS. He was, in fact, the last chief mechanical engineer of that railway, and introduced several excellent steam engine designs, as well as ordering the first express diesel- electric locomotives to run in the UK.

Continuing the dynasty, H.A. Ivatt's daughter married Oliver Bulleid, who gained distinction with the Great Northern and the LNER, before going to the Southern Railway as chief mechanical engineer. During and after the Second World War Bulleid designed some of the most remarkable locomotives ever to run in Britain.

On his retirement from the Great Northern Harry Ivatt was followed by Herbert Nigel Gresley, who was to become an even more notable engineer, and one of the two most prominent locomotive men of the inter-war period. A surprising number of famous locomotive engineers were, like Ivatt, sons of the clergy, and Gresley was the third Great Northern chief in succession to have a minister as a father.

Born in Edinburgh in 1876, he was the son of the Rev. Nigel Gresley, rector of Netherseal, near Burton-on-Trent. His grandfather was the Rev. Sir William Nigel Gresley, 9th baronet. (Most of the male members of this family had Nigel among their Christian names.) Gresley was sent to Marlborough College, where he displayed a keen interest in railway engineering. Like Ivatt, he went to Crewe in his teens, as a premium pupil, and afterwards moved to the Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway's Horwich Works, under Ivatt’s old friend Aspinall. One of his postings was as foreman at Blackpool, where he met his future wife. By the time he was 28 he had been appointed assistant manager of the Carriage and Wagon Department of the L. & Y. Gresley was doing very well indeed, but was a young man in a hurry. Realising that his own chief would not reach retiring age for twenty years, and that there was no real prospect of succeeding him, Gresley looked for a company where someone more elderly was currently in charge of the locomotive side.

Recommended by the Lancashire & Yorkshire to the Great Northern, he was taken on in 1905 by Ivatt as carriage and wagon superintendent, at a starting salary of £750 a year. In this job he displayed great flair, bringing in articulated carriages, which he was to develop over several decades.

On Ivatt's retirement in 1911 Gresley, still only 35, and very confident in his own abilities, became locomotive, carriage and wagon superintendent. The chief need was for goods and mixed-traffic engines, and Gresley introduced several types of these. He, too, asked drivers for their opinions of his cab layouts, and had mock-ups made for them to see and comment on. In general, though, while amenable to advice from those of equal rank to himself, he was said not to respond well to any critical comment emanating from subordinates.

Like many other engineers, Gresley was chiefly occupied during the Great War on munitions work, which took up most of Doncaster's resources. For this work he was awarded the C.B.E. After the war he brought out a very large and powerful mixed traffic engine, and in 1922 the first of the famous Gresley 4-6-2 'Pacific' engines appeared.

This was a most notable design, developed from the Ivatt Atlantic, but only a couple had been built before the Great Northern became part of the newly created London & North Eastern Railway. This was formed from seven major companies and many small ones. J.G. Robinson of the Great Central was invited to be its chief mechanical engineer, but declined in favour of a younger man. So the ambitious Gresley began another important phase of his career. Now 46, he had charge on the L.N.E.R. of over 7,000 locomotives, over 20,000 carriages, and 300,000 vans. Eleven railway works were under him.

Among new express engines built at this time was perhaps the most widely-known steam locomotive of the twentieth century, the Gresley Pacific 'Flying Scotsman.’ The locomotive is still in existence, and indeed, still in steam.

Over the next decade Gresley oversaw the design and construction of a number of new types of passenger and goods engine, some markedly more successful than others. His work on carriages continued with the first articulated dining-car set, and electric cooking equipment for restaurant cars. In the 1930s came perhaps the two most spectacular Gresley types. First of these were the 'Cock o’ the North' engines, of two distinct varieties. These were admired by enthusiasts, but had their faults, and were regarded with mixed feelings by some drivers and firemen. Many of Gresley's engines embodied unusual and rather inaccessible features which made them liable to mechanical trouble. This was to become particularly acute during the war years, when maintenance standards fell.

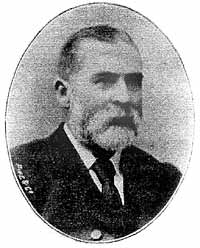

NIGEL GRESLEY as portrayed in ’The Railway Magazine’ in May 1923, shortly after he became Chief Mechanical Engineer of the L.N.E.R.

NIGEL GRESLEY as portrayed in ’The Railway Magazine’ in May 1923, shortly after he became Chief Mechanical Engineer of the L.N.E.R.The second dramatic design came when, in the mid-thirties, the LNER and LMS vied with one another in introducing highly- publicised streamlined express trains to mark the Silver Jubilee of George V and Queen Mary, and the subsequent Coronation of George VI and Queen Elizabeth. The engines built to haul these trains were streamlined, too. The LNER having launched the 'Silver Jubilee’ and the 'Coronation', the LMS responded with its 'Coronation Scot.' One of Gresley's streamlined locomotives, 'Mallard,' achieved the world speed record for a steam locomotive in 1938, recording a figure of 126mph which has never been equalled.

Gresley’s engines however, were like Ivatt's, seen in and around Sneinton mainly in unspectacular roles. Some of his bigger passenger engines appeared at Nottingham Victoria, but the lines to Derby via Colwick, to the Notts coalfield, and to Grantham, saw more of his freight and mixed-traffic types.

In his younger years a handsome man, with crisp hair and prominent moustache, Gresley retained his impressive mien throughout life. A much more assertive figure than Ivatt, he became rather more mellow as he grew older. Following the death of his wife in 1929, his health declined, and he was due to retire in June 1941, on becoming 65. This retirement would have been amply deserved, as Gresley had been head of the LNER locomotive department for 18 years, and of the Great Northern for eleven years before that.

Some had detected a weariness about him by this time, but it was a great shock when Sir Nigel Gresley died suddenly in April 1941. His knighthood was unconnected with the family baronetcy; Gresley had been created a knight in his own right in 1936, and had received numerous academic and professional honours.

Ivatt and Gresley, then, were major railway personalities, and well worthy of remembrance in two of our street names. What other evidence, though, is there in local names of the years when railways were such a noticeable feature of Sneinton?

The Great Northern Close, in the hinterland of Sneinton, could not be more suitably named. Leading from London Road, it passes on the left the old Great Northern London Road High Level Station (now Hooters), and on the right the earlier G.N. Low Level Station, lately converted into the Holmes Place Health Club. Like many people, I was dismayed when the plan to turn Low Level Station into the city's Industrial Museum was summarily scuppered by the City Council, but I admit that, in its new role, the old train shed still makes a fine accent in the local townscape. It is a great pity that the two splendid Great Northern warehouses to the east of it remain in shamefully fire-damaged condition, and are a standing reproach to those who should be safeguarding Nottingham's notable buildings.

I have described Low Level as the Great Northern Station, but it was not quite as simple as that, and this train of thought leads us back to a spot already mentioned, Ambergate Villas. It is regrettable that this name, together with that of the adjacent Ambergate Terrace, disappeared without trace, for Ambergate, even more than Ivatt or Gresley, was a link with the railway origins of this precise location, pre-dating the Great Northern Railway presence in Sneinton.

The line from Grantham to Colwick was opened in 1850 by the ambitiously-named Ambergate, Nottingham & Boston & Eastern Junction Railway. Like many other railway concerns with very long titles, the Ambergate achieved a mileage in inverse proportion to the length of its name. It never got beyond Nottingham in the west, or Grantham in the east. In order to reach Nottingham from Colwick the Ambergate Company had obtained running powers over the Midland route into the latter's station. In 1852 an arrangement was reached for the Great Northern to work the traffic for the Ambergate, but a bitter quarrel arose between the GN and the MR, both of whom sought to gain control of the Ambergate Company. Briefly, this blew up into the seizure of a Great Northern engine by the Midland, who took it to their own sheds and impounded it by removing the access tracks. It was evident that the Ambergate would have to build a line from Colwick into a new Nottingham terminus of its own, but before this was ready, the Great Northern took in 1855 a 999-year lease of the Ambergate's engines, rolling stock, and other property. By the time that the new London Road station was opened in 1857, the trains were in every outward respect Great Northern, but London Road Station (later Low Level) remained the headquarters of the Ambergate Company. In 1860 this was renamed the Nottingham & Grantham Railway & Canal Company, and remained a separate entity until its absorption into the LNER in 1923.

Ambergate, then, is a reminder of a time when local railway competition was fierce and, in many cases, self-defeating. If any further housing development should take place in this part of Sneinton, Ambergate Close or Drive would still be a most suitable name, commemorating this early railway company which had its terminus on the fringes of Sneinton.

Also within the old Sneinton boundaries, though remote from the centre of the parish, was Thorneywood Station on the Nottingham Suburban Railway. It is therefore only proper to offer two cheers here for a couple of names chosen recently for new housing on its site. Two cheers, rather than three, for although they do echo the place’s railway past, they have no local significance at all. Porters Walk is tolerable, but could relate to railways anywhere. The other name, for some inexplicable reason, is Paddington Mews. Perhaps this was the only station that came to mind at the time.

There is, however, another name which admirably reflects Sneinton's railway history, and which is particularly apt for the old Thorneywood Station location. It is that of Edward Parry, who did as much as any man to alter the face of Sneinton in the nineteenth century.

The first draft of this article, in which Parry's claims to a local street name were urged, had just been written when I received a phone call from Ken Brand. He, in his Civic Society capacity, had been approached by the City Council for a suitable name for a further block approaching completion on the Thorneywood Station site. On being asked for suggestions, I immediately put forward Parry, giving my reasons. A more recent visit to the spot has revealed that Parry Court signs are now in situ. So the two cheers must become three, for Parry is at last properly recognized within the historical boundaries of Sneinton.

EDWARD PARRY at the time when, as Resident Engineer of the Annesley-Leake section of the Great Central Railway, he had overall responsibility for the construction of the line through Nottingham. A photograph from ’Contemporary Biographies’

EDWARD PARRY at the time when, as Resident Engineer of the Annesley-Leake section of the Great Central Railway, he had overall responsibility for the construction of the line through Nottingham. A photograph from ’Contemporary Biographies’Now for what this man did. For ten years from 1869 Edward Parry was on the engineering staff on the Midland Railway. Appointed assistant engineer for the new main line between Nottingham and Melton Mowbray, he had oversight of construction of the Trent Bridge at Sneinton, known to us today as Lady Bay road bridge. The Rev. Frederick Smeeton Williams's The Midland Railway: its rise and progress tells how its author met Parry on the site of the bridge works, and heard from him how the piers were to be sunk into the bed of the Trent, and how water was pumped out from the bridge foundations.2

After 1879 Parry held the post of county surveyor for Nottinghamshire, while also practising privately as an architect and engineer. In this capacity, as engineer to the Nottingham Suburban Railway, he, with his assistant J. Greenhalgh Walker, was responsible for major changes to Sneinton. Opened in 1889, the line's chief engineering features here included masonry bridges over Trent Lane, Colwick Road, and Sneinton Dale, together with bridges over the Grantham and Lincoln lines south of Colwick Road.

Parry's splendid arch over Trent Lane is the last surviving masonry bridge of the entire Suburban Line. The fine quality of its blue brickwork offers a sharp contrast to the shoddy materials used in so many recent buildings throughout Nottingham. Another of his works in Sneinton remains to this day, though noticed by comparatively few people. This is Sneinton tunnel, 183 yards long, lying between Sneinton Dale and Carlton Road; its blocked northern portal is visible from a path leading off Carlton Road. Parry's estimate of £194,000 for building the Suburban line was, it must be said, emphatically on the low side, the eventual cost amounting to over £260,000.

Edward Parry's links with the locality were further emphasised by his posts as chairman of the Railway & General Engineering Co. in Meadow Lane, and as a director of the Nottingham Brick Company. The latter had sidings connecting with the Suburban Line, one of them running under Thorneywood Lane (now Porchester Road) from Thorneywood Station.

As one of the notable passengers in the first train over the line, on 2 December 1889, Parry was witness to an absurd contretemps at Trent Lane Junction; this story has been related before in Sneinton Magazine, but bears repeating.3 The inaugural train had travelled only the few hundred yards from London Road Station to Trent Lane, when it was halted by a representative of the contractor, waving a red flag as he stood between the rails. For some time the railway company had been in dispute with the contractor, Edwards, who had stated that he would still be in possession of the line on the opening date. The Nottingham Suburban Railway had accordingly obtained an injunction, quite ineffective, to prevent his interfering with the opening. The officials on the engine’s footplate heard Mr Edwards's doughty representative assert that the line was still in his employer's hands, and that the railway company and its passengers were therefore trespassing.

The Great Northern's district engineer retorted that, the protest being a purely formal one, the train should go on, and Edwards's man, a Mr Colson, stoutly indicated that he would move only if forced to. As the Nottingham Evening Post put it with impressive understatement: 'Upon this the order was given to put the steam on the regulators and the engine moving, Mr Colson was obliged to slip off the line but he placed the flag on the rail and the train ran over it.'

As if to further emphasize the farcical nature of these goings-on, Edwards the contractor, together with his agent, was, on the train’s arrival at Thorneywood, reported for travelling without a ticket.

By the late 1890s living at Woodthorpe Grange, Edward Parry was appointed resident engineer for the Annesley to Rugby section of the Great Central Railway. This involved him in the tremendous engineering works which brought the route through Nottingham, and involved the creation of Victoria Station. This must have been a happy achievement for Parry, as in the 1880s he had prepared plans for a most ambitious scheme to build a Nottingham Central Station on a site north of the Great Market Place. This ten-acre development would have stretched from the Theatre Royal as far as Coalpit Lane (now Cranbrook Street), and would have entailed the realignment of a lengthy piece of Parliament Street. It came, of course, to nothing; one can only speculate about what Nottingham’s railway network would look like today, had this work ever been carried out.

Like Ivatt and Gresley, Parry was a striking figure, possessing a good head of hair, and a fine white moustache and beard. He died at Leamington in 1920, having been born in North Wales 76 years earlier.4

Now that Parry has received due commemoration, we may hope that Ambergate will be one day added to the list of Sneinton street names, satisfying as it does the twin criteria of euphony and local significance.

In time, Sneinton may even see streets named after its two pre-eminent men. Railways can have played at best a minimal part in the life of George Green, who died only two years after Nottingham saw its first railway. William Booth, on the other hand, lived until 1912, the high noon of the British railway network. He travelled by train many times, and when, in November 1905, he came to Nottingham to receive the Freedom of the City, General Booth arrived via the Great Central at Victoria Station, engineered under Edward Parry’s direction only a few years earlier. Unaccountably, neither Green nor Booth has a street named after him in Sneinton.

|

|

|

| A view from Gresley Drive, looking east towards Meadow Lane. (Photo. Gilbert Clarke.) | The new face of Sneinton Hermitage, looking towards the city: MARHAM CLOSE is the first turning on the left. (Photo. Gilbert Clarke.) |

REFERENCES

1. ’The strange story of London Road Station.' Sneinton Magazine 5, Summer 1982

2. 'A noble structure: the story of a local railway monument.' Sneinton Magazine 21, Summer 1986

3. 'The strange story of London Road Station.' (See 1 above)

4. 'About chaps: Sneinton connections in Contemporary Biographies.' Sneinton Magazine 67, Summer 1998

Technical details have been kept to a minimum in this article. It is hoped that those which have been unavoidable have not marred the enjoyment of any reader uninterested in railway history.

I thank Dave Ablitt, who read the draft of this article, and offered helpful comments.

< Previous