< Previous

BY THE OLD CANAL:

London Road in the 1920s

By Stephen Best

I found my love by the gasworks croft,

Dreamed a dream by the old canal,

Kissed my girl by the factory wall,

Dirty old town: dirty old town.

(Ewan MacColl)

ALTHOUGH THE OLD SNEINTON PARISH boundary ran east of it, London Road is now regarded as the western edge of Sneinton's sphere of interest. Indeed, few areas have figured more prominently in the aims of Sneinton Environmental Society than that surrounding London Road Low Level Station.

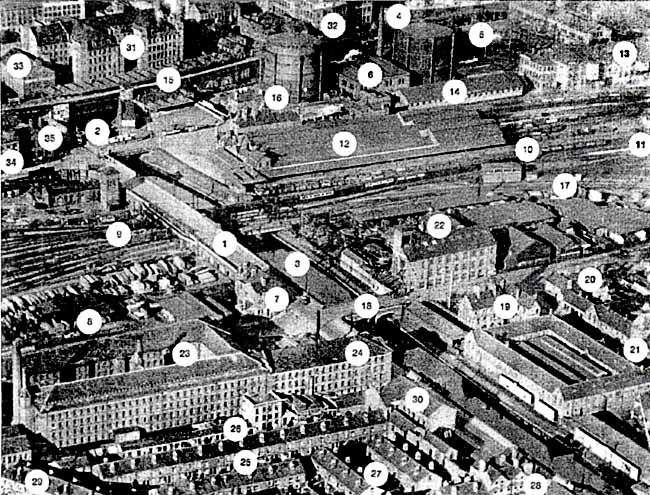

This photograph of the neighbourhood is one of a series of aerial views of Nottingham taken during 1926 by Surrey Flying Services. Although by no means flawless, it admirably shows a landscape formed in the generations that followed the Industrial Revolution. Three quarters of a century later, much of what we see here has disappeared. A great deal had already gone by 1994, when the photograph was first discussed in print.1 Almost a decade further on, further significant alterations have taken place, and the view is now of considerable historical interest.

The oldest element visible in this piece of Nottingham is London Road itself (1). Its ancient name, the Flood Road, is self- explanatory, the road having carried travellers over the flood plain of the Trent, often inundated by the river. In 1796 an Act of Parliament was obtained 'For raising, maintaining, and keeping in repair, the road from the north end of the Old Trent Bridge to the west end of of St Mary's Churchyard...' The Flood Road was subsequently rebuilt on a renewed range of embankments and bridges, and, consequent on the construction of the Nottingham Canal, realigned slightly to the west of its previous site. Of key importance to the town in peace and war, the road was for centuries a vital link for the town, as its only exit to the south.

The few vehicles visible in London Road in the photograph include a tram, travelling in the direction of Trent Bridge, and probably on route no. 7 from Radford to London Road. This may be spotted almost opposite the road bridge spanning the canal near the top of the picture (2). Tramlines would continue to be a feature of London Road until 1935, when the service was converted to trolleybus operation. Now, almost thirty-eight years after the last trolleybuses ran in Nottingham, the new tram route terminates at Station Street, a couple of hundred yards off the picture to the left.

As just mentioned, navigable waterways arrived on this scene in the 1790s. The Nottingham Canal, which played a large part in forming the character of the area, was nearly fifteen miles long, linking the River Trent at Sneinton with the Cromford Canal at Langley Mill. In our picture it runs - as it still does today - along the right-hand side of London Road (3), turning sharp left (west) just beyond the railway bridge close to the upper end of the view, and just out of sight of the camera.

In 1835 a branch waterway from it was opened, converting this point of divergence into a T-junction. Leading away to the east, the Poplar Arm extended for some 300 yards before making an end-on junction with Earl Manvers' Canal. The line of the Poplar Arm follows that of the Boots warehouses behind the railway line on the viaduct; they stand on the northern bank of the arm. The Earl Manvers Canal, whose name suggests a grandeur it never possessed, ran further east to Hermit Street and Sneinton Hermitage, where there was a wharf for the handling of coal and other cargoes.

The Sneinton end of Earl Manvers' Canal was shortened in the 1890s, when part of its site was taken for the new Great Northern Railway line into Victoria Station, built on a viaduct along the Hermitage and Manvers Street. (By this date the canal had long been owned by the GNR.) Fifty yards or so before Earl Manvers' Canal was reached, another branch, the Brewery Arm or Cut, curved away from the Poplar Arm back to London Road, behind the Boots warehouses beyond the railway. As late as 1880 malthouses off Pinder Street still had direct canal-side access to the Brewery Arm. This location between canal branches gave the site its name: the Island, later Island Street. A more accurate description of it, however, would have been the Peninsula. The mouth of the Brewery Cut is, with the eye of faith, faintly discernable here behind the gasworks chimney (4).

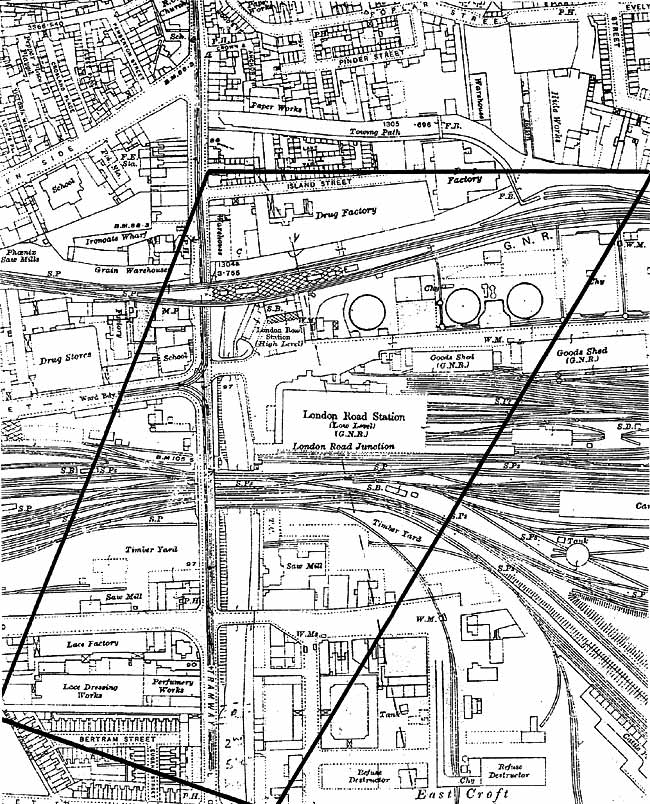

THE AREA COVERED BY THE PHOTOGRAPH, as shown on the large-scale map of 1915 and after.

Another part of the waterways network on this site must be briefly referred to. This was the short-lived Westcroft Canal, authorised in 1839. Serving coal wharves, it ran westward off the Nottingham Canal, just north of the present-day Queen's Road, and rejoined the main canal to the east of Carrington Street. Falling into disuse within twenty years of its inception, it was soon engulfed by the second Midland Railway Station, opened in 1848. It is, however, clearly shown on maps of 1851 and 1861, turning north and running under the railway line.

After the canal, the next major industrial feature of the area to appear was the gasworks, first constructed in 1819 by the Nottingham Gas Light & Coke Co. at Butcher Close. This lay north of the Poplar Arm of the canal, not quite in the area covered by the picture. The 1830s saw five gasholders in use, the company having by then acquired part of the Island site. In the 1850s, following the Nottingham Inclosure Act of 1845, further land was purchased at Eastcroft, and works established there. In 1872 the Corporation took over Eastcroft Gasworks, which by the following decade was capable of producing two million cubic feet of gas per day. Rebuilt in 1933-34, the works remained in use until well after the Second World War. Here, in the 1920s, three gasholders are visible (5), the one on the right quite empty, or temporarily out of use. The retort house can clearly be seen between the two full gasholders. (6).

Queen's Road has already been briefly alluded to. In December 1843 the young Queen Victoria made her first and, as it turned out, her only visit to Nottingham. Travelling with Prince Albert from Chatsworth to Belvoir Castle, she had to transfer from rail to road in Nottingham, the most convenient railhead for Belvoir. At this date the first Midland Counties station was still in use, situated away beyond the left-hand edge of our view, on the canalside west side of Carrington Street.

It was realised that Her Majesty, on this journey from Duke to Duke, would, in traversing Nottingham, be obliged to ride in her carriage along a route compelling her to glimpse the slums of Canal Street and Leenside. Stung into action by the prospect of this calamity, and determined to prevent it, the Corporation ordered that a new road be laid out just to the south of the Westcroft Canal. This was completed in what must have been record time, the royal pair being whisked along it to the Flood Road and the outskirts of town, and so spared a view of such idyllic spots as Hornbuckle's Yard, Foundry Yard, and Knotted Alley. In consequence they quitted the town having seen virtually nothing of it.

That evening the Mayor, Sheriff, and 220 other gentlemen, their enthusiasm apparently in no way diminished by the extreme brevity of the royal visit, sat down to a celebratory public dinner at the Exchange Hall. The hurriedly constructed thoroughfare was named Queen's Road to commemorate the great day.

Queen's Road is the side-turning off London Road, opposite the bridge, spanning the canal in the centre of the picture. At its corner stands the prominent General Gordon pub (7), dating from the 1880s, and named after 'Chinese' Gordon, the iconic British military hero who died in Khartoum at the hands of the Mahdi's followers in 1885.

To the left of, and behind, the public house is the timber yard of Nixon, Knowles & Co., with its own railway siding - two wagons can just be made out, one with its side door open. (8).

Perhaps the greatest impact of all upon the area in the photograph was indeed made by the railways. Here, as all over the country, they had followed the canals after a generation or two, then set about taking over and, eventually, supplanting them. Typically, the Nottingham Canal had begun to suffer severe losses in its profits through railway competition, before in 1845 its board determined that a merger with the railways was inevitable.

The railway history of this locality has been recounted several times in Sneinton Magazine, but a summary will spell out how the lines shown here came to be built.

The original Midland Counties line terminated in Nottingham, at that inconvenient station opened in 1839, and patronised by Victoria and Albert. The line from Derby to Nottingham was extended to Lincoln in 1846, and after two years of extremely awkward operation from the old station, its successor in Station Street was opened in 1848. The present Midland Station buildings on Carrington Street Bridge replaced this in 1904, and we see the tracks leading into and out of this third station on its east side running just above Nixon, Knowles's premises (9). Beside the line, near the corner of Station Street, is a group of characteristic railway buildings. The low building is a workshop or store, perhaps - is the tall one a hydraulic tower, for powering machinery?

An eleven-coach train has just left the station, and is threading its way on to the Lincoln line. London Road Junction signal box partly obscures the locomotive, which is in any case too blurred in the photograph to be identifiable. (10) This line to Lincoln, stretching the full width of the picture, and spanned by London Road bridge, is the only one seen here which remains open today (11). Nowadays it also carries traffic to Grantham, and beyond, which, as will be explained, went in 1926 via London Road High Level Station.

Immediately above the Lincoln train and the two rows of wagons on adjacent lines are the buildings and extensive train shed roofs of London Road Low Level Station (12), opened in 1857 after a lengthy dispute between the Midland and the Great Northern Railways. The Great Northern, working the line on behalf of the Ambergate Company2, who owned the line, had enjoyed the use of the Midland Station ever since the Ambergate's line to Grantham opened in 1850. Two years later, however, when the Great Northern main line to Kings Cross was inaugurated, the companies had fallen out rancorously over the Great Northern advertising its own route to London, in direct competition with the Midland, whose station it was using here. This proved too much for the patience of the latter, who impounded a GN locomotive, and effectively imprisoned it in a shed at the Midland Station. Legal proceedings failed to sort matters out to the satisfaction of both parties, and by blocking the Ambergate's through traffic rights, the Midland was able to compel the Ambergate Company to unload all its goods cargoes at Colwick, from which point they had to be conveyed into Nottingham by cart.

Having secured in 1855 a 999 year lease on all the Ambergate Company's effects, the Great Northern speedily got on with the tasks of securing its own route into Nottingham, and of building a station worthy of its status. Accordingly the new line was constructed from Colwick, and ran side by side with the Midland line into the town. Here a splendid station was designed by the Nottingham architect T.C. Hine, who also provided a corn and goods warehouse nearby.

Thomas Chambers Hine was arguably the most distinguished Nottingham architect of the nineteenth century, whose previous work for the lace-manufacturing Birkin family had secured for him the commission to design this highly visible and prestigious station. (The Birkins had a financial finger in the railway pie.) Hine was also responsible for other stations along the line to Grantham - Radcliffe: Bingham (perhaps the best of them): Aslockton: Elton & Orston.

It has been stated by more than one writer that London Road Low Level Station incorporated portions of Eastcroft Hall. Although, no doubt, a sincere tribute to the grandeur of Hine's designs, this assertion was quite untrue, no such place as Eastcroft Hall ever having existed. It would be interesting to know where this canard originated.

The new station opened on 3 October 1857, acquiring in the 1870s further traffic from the Great Northern's routes to Derby, Pinxton, and Newark. Another railway company arrived on the scene in 1879, when the GN/London & North Western joint line from Melton Mowbray and Market Harborough opened. The 1880s saw the GNR’s Leen Valley line built, and, a year or two later, the Nottingham Suburban Railway, worked by the Great Northern. The latter company's Leen Valley extension of 1898 brought Low Level Station to its high noon of activity, and in 1899 seventy-one passenger trains arrived here daily.

Such an intensity of traffic was to last for only a very short time. The construction of the Great Central main line to London (Marylebone), and the consequent opening of Victoria Station (jointly owned by the GC and GN railways) saw almost all the passenger traffic diverted away from London Road Low Level. From then on it retained only a rump of its train services - on the GN/LNW Joint line, and worked by the LNWR. These continued to run, latterly under the LMS, until 1944, when they were diverted into Nottingham Victoria Station.

Hine's goods warehouse at London Road Low Level (13) was also of great interest, having its first floor suspended from the roof by iron rods. This resulted in a ground floor uncluttered by columns, so allowing railway sidings to run right into the warehouse for loading and unloading. The warehouse, with its prominent sack hoists, stands here on the northern edge of the goods yard. Attached to it is the office block, in which traffic was invoiced and waybilled. Immediately to the left of this is a Jong low goods warehouse, constructed of timber; originally built for the London & North Western, it was for many years occupied by the LNER signal and telegraph engineers (14).

The route into Victoria can be seen on the viaduct between the gas holder and the Boots warehouses. The long island platform roof of London Road High Level Station (15) has its west end built over the canal and London. Road. The station nameboards informed the traveller that this was the place to alight for the cricket and football grounds.

The station’s wide forecourt at ground level is quite empty, as memory suggests it often was. Beyond the forecourt is the entrance awning, to keep the rain off prospective travellers. Such a lavish canopy at London Road High Level was perhaps an unnecessary luxury, but no doubt the GN did not want its new station to look too meagre, when compared with the one next door which it had rendered largely redundant.

Just to the left of the awning can be seen the parcels hoist; and to the east of the station frontage, with a gasholder towering over it, is a handsome Italianate villa (16), residence of the joint station master of the two London Road stations.

A further rail route in. the picture remains to be mentioned. London Road Junction signal box was the point of divergence of the Midland Railway's last link in its main line to London. This line, seen curving to the right in front of the box (17), ran from Nottingham, to Melton Mowbray. There it joined the existing line through Oakham to Glendon Junction just north of Kettering.

Opened to passenger traffic in 1880, the Nottingham-Melton link cut a mile or two off the journey to St Pancras, and avoided Trent and Leicester. Most of the Midland's London to Leeds and Bradford expresses thereafter used this route, the Manchester trains going via Leicester as before.

Opposite the end of Queens Road, and on the east side of London Road, is a two-arch bridge (18), built in the 1850s, and carrying a wide roadway into Eastcroft Depot. As already mentioned, the considerable acreage made available here by the Inclosure Act enabled the Corporation to plan and gradually construct an extensive public services complex. Development here took place quite slowly over several decades; the sanitary wharf, for the disposal of night soil3 by canal boat, was among the early facilities here. Over the years Eastcroft housed, among other things; a refuse destructor: pumping station: Works & Ways Dept: public mortuary: and hide, skin and fat market. What survives today, although much reduced in extent, nonetheless includes interesting specimens of Victorian municipal architecture, almost entirely overlooked and unappreciated by Nottingham people.

Only a corner of Eastcroft can be seen in the photograph. On the south side of the entrance road is the administration block and house of the engineer-in-chief, marked out by its clock tower (19). East of it is a building which originally contained living accommodation for depot employees (20). The mortuary was also formerly sited in this complex of buildings. Immediately to the south of this, on the extreme right hand edge of the view, is the rather picturesque tower of the stable block (21). During the 1920s, at the time of this photograph, other occupants of the Eastcroft include Brown & Co., tallow chandlers: Edward Cope, horse slaughterer: and J. Salisbury, soap manufacturers.

Between Eastcroft Depot and the railway lie the sawmill and timber yard of Ashworth, Kirk & Company (22). Their woodyard, like that of Nixon, Knowles on the other side of London Road, is perfectly sited for railway access. Ashworth, Kirk also enjoy direct unloading facilities from a siding, in this case a line shared with Eastcroft.

The south-western, or lower left-hand hand corner of the photo, displays the area bounded by Queen's Road on the north, and London Road to the east. From the air it appears overshadowed by the huge and impressive complex of factory buildings across the road from the General Gordon.

Most of this is occupied by G. & W.N. Hicking, lace bleachers, dressers and dyers, who have in 1926 have been here for three decades, and will be for many years more (23). The long range with the top inspection floor, forming the left-hand part of the southern frontage seen here, already existed in the 1860s, and the corresponding building facing Queen's Road followed. In the late 1870s and early 1880s these were in the possession of G. Cox & Sons, lace dressers, before becoming Lindley, Wright & Cox for a short while. By the late 1890s, Hicking's were established here.

Built slightly later was the big block facing on to London Road (24), which bears the date 1873 in two places. Its London Road elevation looks uncommonly like a nonconformist chapel, featuring as it does arched windows, a strongly emphasized doorway, and a pediment enclosing a date cartouche and scrolly decoration. This front is unfortunately out of the camera's view, as is the one facing Queen’s Road, which features a rather grand open pediment, prominent clock, and date inscription.

G. and W.N. Hicking should not be left out of this account. One of those astonishingly versatile and hard-working pillars of Victorian Nottingham, George Hicking was successful, not only in the lace trade, but also as a wine and provision merchant. Before embarking on these business activities the remarkable Hicking had, by the time he was 23, attained the rank of station master at Nottingham Midland Station.

His son William Norton Hicking, created a baronet in 1917, was director of many firms, including the associated Hicking & Pentecost and others in the same line of business: Lindley & Lindley, Dobsons & M. Browne, and Lamberts. Also on the board of the Westminster Bank, W.N. Hicking lived for many years at Brackenhurst Hall, near Southwell.

This 1873 block nearest London Road is marked on large-scale maps as cabinet works or perfumery works. For some years in the 1890s it housed W. Lawrence & Son, a furniture manufacturing firm well remembered for its works at Colwick Vale. Here the building is in the hands of Boots, who have occupied it since the turn of the 19th/20th centuries. Formerly used by their perfumers, it is tenanted in 1926 by the company’s veterinary department.

Along the south side of the long Hicking’s factory range runs Bertram Street, a cul-de-sac (25) whose existence was no doubt unsuspected by 99 per cent of Nottingham residents - certainly by this writer. The dwellings in Bertram Street, like their near neighbours in Eugene Street and along the eastern end of Crocus Street, are a late addition to the built-up Meadows landscape; they date from the 1880s.

THE TINKER'S LEEN from London Road, as it appeared late in 2003. The building spanning the water has now been demolished.

THE TINKER'S LEEN from London Road, as it appeared late in 2003. The building spanning the water has now been demolished.Between, the factory and Bertram Street runs the Tinker’s Leen, quite invisible to the camera (26). This stream, a tributary of the Leen, and the result of alterations to its course, leaves the Nottingham Canal by a weir just east of Castle Lock in Wilford Street. It flows to London Road, before running under the street and canal en route to its outfall in the Trent. During the nineteenth century the Tinker’s Leen had been a significant canal overflow channel, while also making an important contribution to the drainage of the Meadows.

Access to Bertram Street is via the short Eugene Street (27) - who, incidentally, were Bertram and Eugene? The latter runs off Crocus Street, at whose corner with London Road stands the large and imposing Norfolk Hotel, also opened in the 1880s (28). The houses set at an angle in the bottom lefthand corner of the photo are a little older than the others. They stand in Trent Bridge Footway (29), which runs here from Crocus Street, across the Tinker's Leen, to Queen's Road. Although it not apparent in this view, these houses are surprisingly charming, with bay windows and small front gardens. Trent Bridge Footway follows the course of an old pedestrian path through the Meadows, reaching Station Street by means of a footbridge over the Midland Station.

Situated in London Road between the Norfolk Hotel and the Boots premises is the wholesale ironmongery concern of Walter Danks & Co. Ltd, also iron and steel merchants, and builders of agricultural implements (30). While quite new, in the early 1890s, the ground floor showroom of 'these spacious stores' had received favourable notice in Nottingham Illustrated: 'This large frontage being utilised for the display of stock by means of several attractive plate-glass windows.' The founder of this long-lived business was for a time a Sneinton resident, living in Victoria Avenue, off Sneinton Dale.

Danks's stands on the site of the Chainey Flash, one of two large pools in the old Meadows. The old Flood Road skirted these when conditions underfoot allowed, but when floods made such diversions out of the question, had crossed the pools by means of wooden bridges. When the weather did not compel their use, the bridges were stopped up by large chains fastened across them. The Chainey Flash still appears on Tarbotton's 1877 map of Nottingham, and a faint trace of it can be seen on the following Ordnance Survey plan, published in 1881.

The last major industrial influence to arrive on the scene has been referred to throughout this article. Boots, the dominant feature of the town end of London Road, came to Island Street in the 1880s. Here they initially took over, as their wholesale department, three big rooms in Thomas Elliott's cotton doubling factory. Eventually all the old buildings were modified and improved, and a great many new buildings added (31). Boots took advantage of cheap land and property prices, occupying in due course the whole Island site with factories, warehouses, laboratories, and printing works; public road access was shut off by gates.

Island Street was convenient for road and rail transport, and canal access enabled barges to deliver the coal that kept the Boots engine house running. (The company owned their own boats for this purpose.) The buildings seen here range from the old and higgledy-piggledy to the recent and up- to-date. The one visible between the gas holders (32) bears the legend 'Boots Manfg. Chemists,' while the sign on the left-hand building fronting on to London Road reads, I think, 'Boots Pure Drug Company.' (33)

On the other side of London Road, another branch of the Boots empire can just be seen towards the end of Station Street. This is part of the printing and stationery department of Boots Cash Chemists (Eastern) Ltd. (34) Next to it, at the corner, stands St John Baptist Trust School (35). The parish church of St John, Leenside, was not far away, in Canal Street. Completed in 1844, it was built to the designs of Scott and Moffat to serve the very poor Narrow Marsh neighbourhood. The church just failed to achieve its centenary, being wrecked in Nottingham's most severe air raid, during the night of 8- 9 May 1941. The ruins remained for some years after the war, and very dramatic they seemed to a small boy.

The parish school we see here had been built as the parsonage, later serving briefly as the Sunday School. The original school, dating from 1847, had been next door to it, on the canal bank, but was demolished at the end of the nineteenth century to make way for High Level Station and the adjacent railway bridge.

Here, then, laid out before us, is London Road in 1926: a well-known workaday Nottingham thoroughfare as it was almost eighty years ago. As stated at the beginning of this account, much has changed since then. It is now time to find out what remains of the landmarks in our picture, and to see what became of those which are no longer there.

We start at the very top of the picture with the Boots Island Street factories. To begin with, no trace is now left of anything remotely resembling an island. The Poplar Arm and the Brewery Cut have been filled in over the past couple of decades, and a newcomer to Nottingham would have no idea that they had ever existed; except, perhaps, for the boat turning area at the junction, which gives just the slightest hint that the canal once extended east of it.

Not only this, but the old Boots buildings are entirely wiped out, the last of them demolished in 1996. There had of course already been many alterations and demolitions before the last of the factories and warehouses came down. Air-raid damage accounted for some buildings, while Boots continued to modernise the site through the decades following the 1920s. By the sixties, as Ray Banks was to write, 'The writing was on the wall for the Island Street Factory.'4 Apart from the name 'Island Business Quarter,' nothing survives today.

Some cities have dealt successfully with the redevelopment of an industrial area, while still managing to retain some of its past character. Whether or not it would have been possible to convert some of the factory buildings here, or at least to indulge in 'façadism,' one cannot say. There does, however, seem to have been a determination to remove all vestiges of what had been here before.

The resultant large flat area is crossed by the nondescript road named City Link, and dotted with modern (or post-modern) buildings that some people may conceivably find inspiring or lovable - BBC East Midlands HQ: Premier Lodge Hotel: Independent Living Funds: NHS Direct: and others. It is all a matter of taste, and there are indeed many worse new buildings than these. One cannot help feeling, however, that they could be anywhere, for little or no sense of place survives. At least a viewing platform has been provided on London Road, above the canal turn, where one may sit and contemplate the scene. For a brief while it was possible to gaze across from here to Sneinton on its nearby hill: not any more, though - the longer view is blotted out by new buildings.

Not only have the factories and the canal arms been expunged, but the traces of the locality's old railways have also been thoroughly pruned. The viaduct on which High Level Station stood was demolished in piecemeal fashion after the last freight trains ran in 1974, the bridge over London Road being quickly removed. Just a small section of the viaduct, four arches in length, lurks behind the ground-floor station building.

High Level closed in 1967 when passenger trains were diverted into the Midland Station by a new - more correctly, reinstated - connection at Netherfield, which allowed trains for the Grantham line to be re-routed from the Midland Station. The High Level station building at ground level has had several changes of identity since then. As a venue for eating and drinking it has been variously the Grand Central Diner, Sam Fay's, and Hooters. It is good that the names have reflected the building’s railway history, but unfortunate that none of these had any connection with the Great Northern. The Grand Central is, of course, a station in New York - the first Grand Central was designed to rival St Pancras - while Sir Sam Fay was general manager of the Great Central.

Much regretted locally was the removal and subsequent cutting-up in 1997 of the fine girder bridges spanning the canal. Of course they were mere relics, and of no practical use, but they were in their own way monuments, and there is nothing like them left in Nottingham.

To the east of High Level Station, the gasworks are gone without trace. Much of their old site, together with part of the Island, is now covered, one might even say crushed, by the new Boots the Chemists London Road Warehouse, which, like many modern buildings of its sort, is vast and characterless, and unlikely to inspire affection in any onlooker.

It is hard for anyone who has been associated with Sneinton Environmental Society to write dispassionately about the next location. If Calais was carved on the heart of Mary Tudor, then London Road Low Level will be found similarly inscribed on ours.

Following its closure to passenger traffic in 1944, Low Level led a varied life. Until 1967 it served as a general goods station, becoming a year later Nottingham's rail parcel concentration depot. This last role ceased in 1981.

Little attention had been given to the building for years, but new interest was aroused by the publication in Sneinton Magazine during 1982 and 1983 of two articles. The first was a short historical survey of the station, while the second introduced Dave Ablitt's proposal that it be converted into a Museum of Industry and Transport.5

A decade of great effort and real hope followed, and, as late as Summer 1994, Industrial Heritage Challenge featured a cover photograph of the handing over of the station building to a partnership which would develop it as a leisure, retail and museum complex.

Not all had been easy going. The station building had been partially restored by a Manpower Services Commission team working for Family First, but had subsequently been allowed to sink back into dereliction and neglect through insufficient site protection on the part of the authorities.

The City Council’s attitude to the museum plan had at times seemed ambivalent, but it came as a profound shock when, after having promised support, the council decided to sell the station to a property developer, so preventing the Museum Trust from accepting the £400,000 of EU money it had been offered, and effectively killing the project.

Such an attitude to the city's museum resources seemed incredible, in the light of Nottingham’s previous highly praiseworthy record in this field. Other recent events, however, suggest that museum provision has sunk unacceptably low in the order of priorities of the city's councillors and officials.

The subsequent conversion by Holmes Place Health Clubs has given the building a new use, although its survival had not been in doubt since acquisition by City Challenge, which had handed it over to the council. The former station continues to make an important contribution to the Nottingham townscape; its present appearance and condition are a credit to all concerned, and it is no fault of the present occupants that Low Level Station is not freely available to the general public as it would have been as a museum.

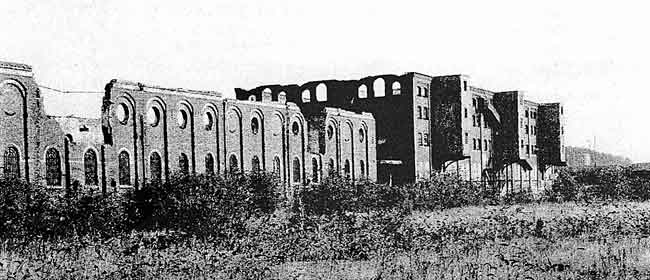

SNEINTON'S INDUSTRIAL HISTORY HERITAGE IN FEBRUARY 2004. The two Great Northern Railway warehouses in their current state.

SNEINTON'S INDUSTRIAL HISTORY HERITAGE IN FEBRUARY 2004. The two Great Northern Railway warehouses in their current state.We have, alas, not finished with the vicissitudes of the Low Level site. In 1991 the large wooden warehouse in front of the gasholder was burned to the ground (its site now a car park for the health club,) and in December 1993 the more recent of the two Great Northern warehouses (just out of our picture) was severely damaged by fire, which destroyed its roof. With its burnt-out and botched-up top floor, it presents an appallingly uncared-for appearance.

Worse was to come, for in May 1998 T.C. Hine’s warehouse of 1857 was also ravaged by fire. This nationally important structure had by now already been sold by the City Council, in a confidential transaction. The shell remains, but no one seems to have the will, the money, or the knowledge to deal with it; one reluctantly feels that it is now beyond help. Have any three large buildings anywhere else, so close to each other on an important site, fallen so mysteriously victim to fire? The former office block survives next door to the Hine warehouse, although in a terribly poor state.

The track has of course all been taken up from the former Low Level Station yard, much of which remains empty and neglected land, and the rail layout of the running lines nearby has been much simplified. As described earlier, the line east of the Midland Station is now limited to the route to Netherfield Junction, where since the 1960s the Lincoln and Grantham lines have diverged. Just three sets of rails now lead out of the station, London Road Junction is no more, and the signal box, in common with nearly every other box in Nottingham, has been done away with. Just off the righthand edge of the picture is the location of the new Maintrain servicing depot.

The railway line from London Road function to Melton closed in 1967, but one enduring monument to it survives in Sneinton. This is its girder bridge over the Trent, known in Midland Railway days as Sneinton bridge, or, less specifically, the Trent bridge. Following some years of dereliction, it was put to a new use in December 1979 as Lady Bay road bridge, under which name it remains an important part of Nottingham’s traffic system.

South of the railway, Ashworth, Kirk's sawmill and woodyard are long gone, and the site is now occupied by Hartwell Ford dealers and Rapid Fit tyre, parts and service centre.

Eastcroft depot is much changed, and of the buildings in the picture, only the Clocktower [sic] Building survives, Housing the directorate and reception departments of Nottingham City Neighbourhood Services. It is good, however, to report that the clock keeps correct time. The site of the stable block is a car park, and the building between it and the canal has been replaced by something modern and anonymous. The entire Eastcroft site is now dominated by the massive refuse destructor at its eastern edge, reached via the inspirationally-named Incinerator Road.

We retrace our steps to the corner of Station Street to see how this corner of the photograph has changed. The old Boots building is gone (there was more bomb damage here,) and on its site stands a huge block, now empty, but formerly also in Boots’ possession. This is currently undergoing extensive repair and renovation. Not long after the date of the photograph, St John’s School became a 'Centre for Dull and Backward Children,' finally closing in the 1930s. On this spot there lately stood until recent months an undistinguished modern building that last housed Matthews' Office Furniture.

The eastern rail exit from the Midland Station (since 1969 simply Nottingham station) is, as stated, now reduced to three tracks. The interesting railway buildings in the corner nearest Station Street are gone; almost inevitably, unattractive prefabricated offices and Portakabins now occupy the ground.

Like Ashworth, Kirk across the road, the timber merchants Nixon, Knowles have left the scene. The latter firm, however, is not far away, at Longwall Avenue, on the site of Clifton Colliery. There, alas, it can be reached only by road vehicles. The General Gordon pub was pulled down a few years ago, having latterly been renamed Old Tracks. Its site is now covered, like much of Nixon, Knowles, by the modern buildings of The Health Store's national distribution centre. Adjoining this is a large car park, principally for the use of railway travellers.

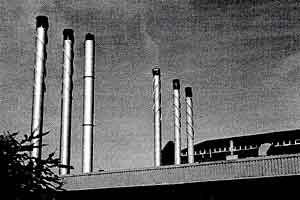

Things are changing on the southern side of Queen's Road. The enormous factories still stand, though a closer look shows broken windows, and vegetation sprouting in the gutters. A currently-disused building lurks behind the very long frontage of over thirty bays along Queen's Road. The 1873 block fronting on to London Road displays on its northern face the name Hicking (UK) Ltd, the more recent title of its 1926 occupants. A board gives the information that the building has been sold for loft and apartment development. The equally long south-facing range seen in the picture is also empty at present, while the factory chimneys on the left-hand edge of the photograph have been removed, together with the building to the west of them.

A report in the Evening Post of 28 October 2003 described how 300 homes are to be created here, through refurbishment and newly-built units. Work has since begun during the winter, and considerable activity is now apparent, with some demolition in progress. By the time this article appears in print, further significant developments may have taken place here. Everything north of the Tinker's Leen will be transformed, and the closeness of the site to the Midland Station and the Holmes Place Health Club is expected to attract many buyers.

A short walk along Station Street reveals that the section of Trent Bridge Footway between Crocus Street and Station Street survives, though now a thoroughfare called Summer Leys Lane. The reality does not, however, live up to the rural promise of this name. Just out of the picture, the more easterly of the footbridges over the station has been pulled down. The public right-of- way across the railway is now diverted to the remaining station footbridge; although it is no longer signposted, no one challenged me when I crossed here.

On either side of Summer Leys Lane the Tinker's Leen may still be seen. When I visited the location in autumn 2003, this watercourse flowed, as now, in the open in a short space between factory premises spanning the stream. The tiny stretch west of the road was comparatively clear, and the water was obviously flowing. To the east of the road, however, all was choked with weeds and rubbish, and the flow appeared minimal. The same applied to those few yards in which the Tinker's Leen emerged from beneath another industrial building, before disappearing under London Road and the canal. A look over the parapet from London Road disclosed a grim and sordid mess - not only vegetation choking the flow, but bottles, cans, and the other usual litter.

In the intervening few months, however, the low, more recent, factory buildings built out above the Tinker’s Leen between Summer Leys Lane and London Road have been demolished, and only the concrete raft upon which they stood remains, still spanning the stream. Some clearance of the watercourse seems to have taken place, and the Tinker's Leen appears to flow rather more freely now than it did. This is emphatically a spot to revisit in a year's time for a further progress report.

THE OLD AND NEW HICKING BUILDINGS from Crocus Street, Autumn 2003.

THE OLD AND NEW HICKING BUILDINGS from Crocus Street, Autumn 2003.The little houses have all gone from Trent Bridge Footway, as they have from Bertram Street, Eugene Street, and the section of Crocus Street seen here. The space formerly filled by these dwellings is now taken up by the modern premises of Hicking (UK) Ltd. In total contrast to the old, these new buildings are of one storey, and predominantly in the prefabricated style favoured nowadays. There is a prominent cylindrical metal tank, but the most eyecatching features of the complex are six very tall shiny metal chimneys, (or what appear to the layman's eye to be chimneys.) with black tops. One of these is considerably higher than the others. These features may not be beautiful, but they are certainly arresting.

Remarkably, the name Eugene Street still exists, though its present holder is laid out a few yards to the east of its predecessor. It possesses no buildings of its own, and serves merely as an access cul-de-sac. Hereabouts are a few surprise survivors from the 1926 photograph. At the corner of Crocus Street the Norfolk Hotel continues in business, with a signboard indicating that it offers accommodation.

Danks’s old ironmongery showrooms on the site of the Chainey Flash pool appear in good heart as the premises of Recliner World. Lower outbuildings, visible between Danks's and Eugene Street in the picture, are still in commercial use. One board bears the name of RBR Builders, and another, more surprisingly, that of the Central Stage School of Dance and Drama. The latter, however, appears to be no longer in business, and is not listed in any current directory consulted.

It would be interesting to see an aerial photograph taken today from the very same spot chosen by Surrey Flying Services all those years ago. Such a picture would further illustrate the radical change which has affected inner city areas everywhere.

This is not a beautiful part of Nottingham, but it has its high points. Much of our city's industrial past can be savoured and understood by looking at it, and there is still fine old workmanship to enjoy and admire. Just look at Low Level Station: the canal bridges: Eastcroft's original buildings: Hicking's factories: and Danks's handsome display windows. The Eastcroft clock tower and Hicking's also form surprising and handsome features of the distant prospect from the top of Sneinton Road - the bus stop by the shops opposite Notintone Street is a recommended vantage point.

THE UNEXPECTEDLY WOODED FACE OF LONDON ROAD from the canal towpath, 2003.

THE UNEXPECTEDLY WOODED FACE OF LONDON ROAD from the canal towpath, 2003.And, from the canal towpath, another most unexpected view can be relished, especially delightful because to experience it one has to be facing away from the monstrous incinerator. Look west. Anglers may occupy the path in the foreground, and ducks the water beyond it. Out of the steep bank opposite, wild flowers grow happily along the foot of a pleasantly weathered brick wall. Over the wall is a backcloth of luxuriant foliage - when I saw it, the trees were in autumn colour. And the exact location of this green idyll? London Road itself.

I am indebted to Dave Ablitt, who read the article in draft and made a number of valuable suggestions. A former chairman of Sneinton Environmental Society, he played a crucial part in the creation of the Museum Trust. His detailed knowledge of the recent history of the former London Road Low Level Station site has provided many of the facts concerning its disposal. To him go my warmest thanks.

This short article is dedicated to Dave, and to Eddie Woolrich, another to have made a major contribution to the latter-day saga of London Road Low Level.

Throughout the article, 'now' means February 2004.

1. S. Best. ' Seventy years ago.' Industrial Heritage Challenge 5, Summer 1994

2. For all its comprehensive title, the Ambergate, Nottingham & Boston & Eastern Junction Railway achieved only 19 miles of route, from Grantham to Colwick.

3. the contents of earth privies and pail closets, removed at night-time

4. R. Banks, 'Memories of Boots Island Street (pt 2.)' Nottingham Industrial Heritage 10, Spring 1996

5. S. Best. 'The strange story of London Road Station', Sneinton Magazine 5, Summer 1982.

D. Ablitt. ’London Road Station: a new future?' Sneinton Magazine 11, Winter 1983/84

< Previous