< Previous

THE ALBION OBSERVED:

Sneinton at a Time of Change

By Stephen Best

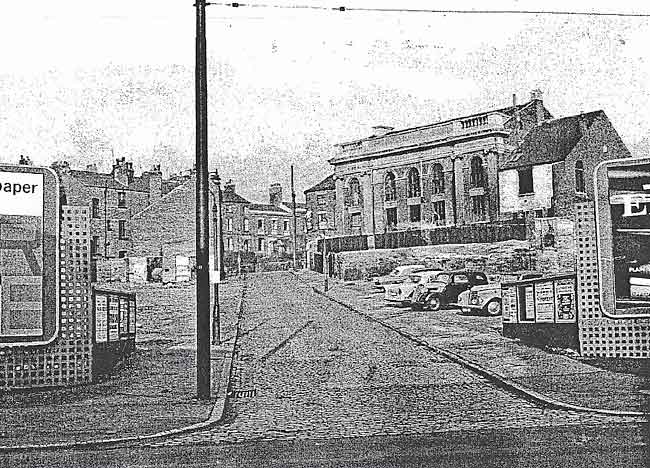

Looking up Bentinck Street to the Albion Chapel and Minerva Terrace (Sneinton Road).

Looking up Bentinck Street to the Albion Chapel and Minerva Terrace (Sneinton Road).THE MOST PROMINENT FEATURE OF Geoffrey Oldfield’s photograph, taken from the comer of Bentinck Street and Manvers Street more than forty years ago, is the Albion Chapel in Sneinton Road. The building will soon be 150 years old, and 2004 has been an important year in its history. Framework Housing Association has recently converted this important Sneinton landmark into 24 flats, to the designs of Allan Joyce Architects, of Bath Street, and Nottingham Civic Society has awarded the work a well-merited Mark of the Month for July 2004.

More extensive accounts of the Albion’s history have been told in earlier issues of Sneinton Magazine, and only a short outline is given here.* The building was designed by Thomas Oliver junior of Sunderland, who was responsible for one of the ‘model’ designs chosen by the English Congregational Chapel Building Society for its new places of worship. 'Adapted by the architect to the site at Sneinton,' it was built under the local supervision of William Booker of Nottingham.

Building began to coincide with the bicentenary of Castle Gate Church, and the chapel opened in 1856. It survived early setbacks and financial hardship to become, under the pastorate of the Rev. Speight Auty, one of the neighbourhood’s most influential places of worship.

By the 1930s it was clear that most members of its congregation no longer lived in the streets immediately surrounding the Albion, but now came from the other end of Sneinton. A decision was therefore made to build a Sunday School in Lichfield Road, off Sneinton Dale, and it was intended that when this was completed a new church should follow it on the same site. The plan was never carried out, and the Albion remained open in Sneinton Road for a further fifty years, becoming, with the union of the Congregational Church and the Presbyterian Church of England, the Albion United Reformed Church.

In 1986 the chapel was united with Parkdale Road Chapel in Bakersfields, which became The Dales United Reformed Church. The former chapel was thereafter used by the Macedon Trust as a day centre, and as a night hostel. During 1989 and 1990 a heated controversy arose in the pages of Sneinton Magazine about the role which the Albion was then fillfilling. No planning permission for change of use had been granted when the magazine aired this dispute, and argument remains as to whether such permission was ever given before this latest conversion was proposed. John Hose and Dave Ablitt, both deeply involved over many years in Sneinton development, conservation and public debate, are adamant that permission was never given for the building to be used as a night shelter.

The accompanying view of the chapel shows the Albion as it appeared a few years after its centenary. The date is April 1963, by which time the redevelopment of the densely built-up area of New Sneinton was already well advanced. The photograph leads the eye up an almost-vanished Bentinck Street, and although it may not show the Albion (or indeed, Sneinton) in the most glamorous light, it is wonderfully evocative of the old Sneinton on the verge of extinction.

Denuded here though it is of neighbouring houses already pulled down, the Albion’s true status as part of the local townscape is still apparent, rising as it does above the surviving nearby buildings. This is in marked contrast to its present-day plight, squeezed up on one side against a sheltered housing complex, and with its scale diminished by the three huge tower blocks which replaced the multitude of small houses lying between Sneinton Road and Manvers Street.

The main (north) front of the chapel, facing Sneinton Road, is invisible from this viewpoint, but complete demolition of that side of Bentinck Street has revealed the side elevation of the building. The two end bays are embellished with Ionic pilasters, and the balustrade above these end bays is pierced. The three middle bays are plainer, with a filled-in, rendered parapet, and without pilasters.

Also noticeable here is the Albion’s least attractive feature, the rear extension of 1904. This was a replacement for a smaller original vestry which had harmonized far more closely with the architecture of the main body of the chapel. The west side of this extension, seen here, is done no favours by the white glazed brickwork, which at one time reflected light into adjacent properties. The east side is much better, featuring a round headed window and doorway.

Plainly visible here is the Albion’s situation on a sizeable sandstone outcrop, not nearly so evident in 2004. Other buildings once existed very close to the Albion, and the fragment of brick wall behind the parked cars exhibits what looks very like an upstairs fireplace. The Ordnance Survey large-scale map of 1915 reveals that an outbuilding behind houses in Colton Terrace once occupied this spot. The vanished no. 1 Bentinck Street, whose site lies somewhere at the top end of the car parking area, had for many years been the surgery of Dr Sparrow, later joined by Dr Gendle.

Immediately to the left of the far end of the Albion can be seen a shop in Sneinton Road, one side of which was, until the redevelopment of the neighbourhood, an almost unbroken series of small retail premises. The business glimpsed here is Wright’s grocers at the junction with Beaumont Street. Above the shop window a large advertisement adorns the elegantly curved wall which turns the comer.

Close to this are two poles, which at first glance appear to be one. The smaller is a telegraph pole; the taller a sewer vent pipe - one just like it can still be seen in 2004 in Sneinton churchyard, just to the right of the Dale Street entrance. On the other side of Sneinton Road from Wright’s are two or three of the rather superior houses which characterized that stretch of Sneinton Road between Haywood Street and Upper Eldon Street known as Minerva Terrace. The three-bay house in the middle, with roof parapet slightly lower than its neighbours, is the premises of D.L. Baguley & Sons, for decades a well-known Sneinton firm of plumbers. Just out of view of the camera on the left, a few doors below Baguley’s, was a house which bore the professional nameplate of cMr Sissons, Dentist.'

The few dwelling houses remaining in Bentinck Street here are probably already empty by the date of the photo. In the three-storey buildings in Sneinton Road, whose backs are visible here, old-established businesses were closing down or moving elsewhere, if they had not already done so - Charles Brown, furniture dealer, at no. 66: Camill the pork butcher at 64, and Taylor’s pawnbrokers at no. 60. Taylor’s may still be found in Carlton Street, where they display what I believe to be the last remaining traditional sign of three brass balls in the centre of Nottingham.

As viewed here, the Bentinck Street of 1963 may have lost most of its buildings, but nonetheless retains two pleasing features. The carriageway is still of stone setts, which we all used to take for granted, often grumbling when horse-drawn traffic beat a noisy tattoo upon them. But they did add to the character of a town street, as did the lamp posts we see, decently proportioned, and with a grace lacking in much of today’s oversized street lighting.

For all their slender attractiveness, the Bentinck Street lamps must have been harder for lads to climb than the ones which the writer and his friends enjoyed in Forest Fields during the late 1940s. These did not taper, and also possessed a series of regular mouldings and a bulge halfway up which made it a simple matter to shin up and dangle a rope from the cross-arm at the top, so essential for many street games. On one of the Bentinck Street lamp posts here is an official-looking notice, presumably referring to the clearances which have already occurred.

The cars parked on the vacant site are an evocative lot, ranging from what looks like a late-1930s Ford van to models of the late fifties; an eye more knowledgeable than mine would be able to identify all the makes. The one nearest the camera adds a stylish touch to these not- very-smart surroundings. Dave Ablitt, who has kindly read the proofs of this article, tells me that it is an Armstrong-Siddeley, and that the model is probably a Sapphire. If he is in error, which I doubt, I am confident that some other reader will name it.

The post in the immediate foreground forms, I think, part of the supports for the trolleybus wires. In 1963 the no. 44 route from Colwick Crossing to Bulwell Hall Estate still has a couple of years to go, before its replacement by what Nottingham City Transport still called ‘motorbuses.’ The last trolley route was converted in the summer of 1966.

By a coincidence, since the shake-up of Nottingham bus routes a few years ago a quite different route 44 now runs along Manvers Street on its way to Netherfield, Gedling, Mapperley, and thence back into the city centre.

And fixing the date? The bill-stickers provide the clue. On the right hand side of the picture may just be seen one of the once familiar Nottingham Forest posters advertising a home match, complete with the Forester in his tall hat, immortalized in the Football Post. (Thomas Henry Fisher, the Nottingham-born artist who created this figure, and drew all the football cartoons for the paper, was on the Nottingham Guardian staff. He is more widely remembered as Thomas Henry, illustrator of Richmal Crompton’s ‘Just William’ stories.)

The match advertised here is versus Birmingham City on what looks like April 13th. A check of the club’s results over a period of about fifteen years around the date of the Sneinton redevelopments reveals that 1962/1963 was the only season in which Forest played Birmingham during April. And the date was indeed the 13th. Forest, alas, lost two-nil at the City Ground, but still contrived to finish ninth in the First Division table. (Here I should add that the photographer has since confirmed that the view does indeed date from April 1963. It had, however, been fun working it out.)

Other sporting events are advertised here, too; next but one to the Forest bill is an announcement of a race meeting at Leicester, while across the street stock car racing at Long Eaton Stadium is publicized.

There is unexpected irony to be found in the first small poster on the right, next to the big hoarding advertising Wills’s Embassy cigarettes. For a long time I could not make it out, but have come to the conclusion that the notice (apparently another official one) reads: ‘East Midland Mines Have a Powerful Future.’ Further comment seems superfluous.

Having recently had the pleasure of a tour of the inside of the transformed Albion, I wish to record my opinion that it is a credit to all concerned. The Rev. Speight Auty and the earlier founding fathers of the chapel would surely feel that the building’s new role is a thoroughly worthy one, and that the Albion remains a symbol of hope in Sneinton.

My warm thanks to Geoffrey Oldfield, who not only took the photograph forty-one years ago but also allowed its reproduction here, and was kind enough to send me a print almost by return of post.

The interested reader is directed to the following:

‘A great public convenience: the early days of the Albion Chapel. ’ Sneinton Magazine 25, Autumn 1987.

‘The poet and the pastor; memorials to local nonconformists, 2: The Congregationalist,’ Sneinton Magazine 79, Summer 2001.

< Previous