< Previous

TAPPING A PROMISING DISTRICT :

Part 2: Sneinton's own branch railway :

Later developments, decline and closure

By Stephen Best

Manvers Street Goods Station following closure and lifting of all track. This is what remained of the warehouse after the air raid of 1941, and subsequent rebuilding c. 1967. (Photo: Anne Day Collection).

Manvers Street Goods Station following closure and lifting of all track. This is what remained of the warehouse after the air raid of 1941, and subsequent rebuilding c. 1967. (Photo: Anne Day Collection).Part 1 dealt with the planning and building of the London & North Western Railway goods branch to Manvers Street, Sneinton

ON THE FIRST OF JANUARY 1901, THE new century was greeted by a supplement in the The Nottingham Daily Guardian, titled The Nineteenth Century: Progress and development in Nottingham. In a section on Nottingham’s railway history, it described how the LNWR had arrived in the town via its joint line with the Great Northern. ‘Their principal aim was to compete for goods and mineral traffic, the result being the erection of their large goods station at Sneinton Hermitage, whilst their pasenger trains ran into the old low level London Road station, of which they now have practically the undisturbed use. ’

The local press clearly remained well versed in the strategies of the rival companies, and it is of interest that Manvers Street Station was considered important enough for mention in this review of the previous hundred years in Nottingham. The article also pointed out an odd arrangement which followed the opening of Victoria Station in May 1900.

Under this, London Road Low Level continued to be the terminus for the joint line passenger trains, which were always worked by the North Western. Virtually all of the GN’s own passenger services had, however, moved immediately into Nottingham’s new, spacious and very central station. So resulted the anomaly of a Great Northern station almost abandoned by its own passenger trains, but still being used by those of another company.

The short-lived local periodical City Sketches had mentioned in June and July 1898 that Lord Stalbridge, chairman of the LNWR, had visited Nottingham with a number of his directors, but that the North Western were still keeping to themselves their intentions about participating in the new joint station. It seems that nothing came ot this visit, and these rather infrequent joint line passenger trains were not diverted from London Road Low Level into Victoria until 1944.

As mentioned earlier, the 1880s plan for a large Nottingham Central Station came to nothing, and Sneinton escaped the enormous engineering works which this would have involved. The neighbourhood was nonetheless affected by other railway developments in the 1880s. Not only was the Manvers Street Goods branch built, but the Nottingham Suburban Railway was constructed, crossing Sneinton from south to north, with bridges over Colwick Road and Sneinton Dale, and a tunnel between the Dale and Carlton Road.

Then, in the late 1890s, came the building of a new line into Victoria Station from the Great Northern line near Trent Lane Junction. Meadow Lane was crossed by yet another bridge, which brought up to four the number of railway bridges spanning this road, together with a level crossing. The most radical changes seen in the locality, however, were the ones carried out at Sneinton Hermitage in 1897 and 1898. Not only was the new line built on a viaduct along the south of the Hermitage, but the roadway from Lees Hill Footway eastwards, had be realigned to accommodate it.

This necessitated moving the carriageway northwards by about 20 yards, the new course of the road actually being laid where some of the old rock houses had stood. The Nottingham Evening Post of 9 November 1897 reported that all the old buildings at the Nottingham end of the Hermitage rock had now been pulled down, with the exception of the two celebrated local pubs, the Earl Manvers Arms and the White Swan. Work had in fact just started on demolishing the former, while the end of the White Swan was expected within a few days.

During 1900, Mr R.F. Bennett, of the GNR Construction Department, contributed a piece to The Engineer (v 90 p170,) describing recent alterations to the Hermitage. The new roadway had been made fifty feet wide, as agreed with the Corporation of Nottingham. ‘This part of the work was very interesting, as Sneinton Hermitage was probably the oldest part of Nottingham. It passes at the foot of a cliff which was honeycombed with dwellings of prehistoric date...Many of them had to be destroyed for the road diversion, but a number still remain east of the new works.’ These survivors stood between Lees Hill Footway and Hermitage Square; they did not last for much longer, however, and were displaced in 1904 by the handsome houses which are now nos. 1-35 Sneinton Hermitage.

The re-routing of the roadway gave Manvers Street Goods Station one of its more noticeable and impressive features. Once the old buildings in front of the rock face had been done away with, the vertical face of the Hermitage cliff had to be cut back to make room for the new carriageway and pavement. As The Engineer explained: ‘The road abuts against the London and North-Western Railway goods yard on the north side, where a very high retaining wall had to be built. This retaining wall is of no great thickness, as the rock is capable of standing by itself all it requires being a little facing to keep it from the weather. The wall is built of Bulwell stone backed with concrete.’

Just before the Great War the London & North Western overprinted one of its popular picture postcards (the one I have seen is of Oban, but there were probably others) with an advertisement for the facilities available at Manvers Street. The wharves for cattle and mineral traffic received special mention, and it was pointed out that this was the nearest station to the local wholesale markets (just at the other end of Manvers Street.) The company collected and delivered at Basford, Beeston, Carrington, Colwick, Lenton, Netherfield, Radford, Sherwood, and West Bridgford. Also advertised were LNWR express goods services to Nottingham from London, Liverpool, Manchester and Birmingham. The LNWR enquiry and receiving office was still in Lister Gate.

This is, however, one of the very few bits of publicity for the goods station I have seen. When virtually new, in 1889, it had rather surprisingly been referred to in Wright's Directory's short description of Sneinton: ‘The London and North-Western Railway Co. have a small branch from the Great Northern line near Meadow Lane, to the western end of the Hermitage, with a spacious goods station, warehouse and sheds.’

After this, however, few of Nottingham’s official or semi-official publications would grant Manvers Street more than a cursory mention. In contrast to a passenger station, a goods depot went unobtrusively about its daily and nightly routine. Details of improvements to facilities or upgrading of timetables received little general notice, being, on the whole, communicated direct to regular users. There was little opportunity for a branch like Manvers Street to catch the eye of the general public.

While the interested amateur could freely linger on the platform of a passenger station, and watch what was going on, a goods station offered no opportunity for similar activities. Indeed, unauthorized visitors were rigorously discouraged from setting foot on the premises. The possibility of pilfering was a constant preoccupation of the management.

Furthermore, operations at Manvers Street were almost invisible to the passer-by. It was just possible to catch a very quick glimpse of the depot from a train passing on the Grantham line viaduct on the south side of Sneinton Hermitage, while a very long-distance view of the warehouse at Manvers Street could be had from the platform of London Road High Level Station. Pedestrians, as will be described later, had to make other arrangements.

The depot opened, of course, at a time when the railways handled a vast number of single wagon loads for customers, and even smaller consignments. Virtually all long-distance movement of commodities was by rail, with delivery by motor vehicle yet to become an upstart novelty.

For decades the familiar mode of transport seen entering and leaving the Manvers Street and Newark Street gates would be the horse and cart - remember that accommodation for 25 horses had been provided. These would eventually be complemented, and in time supplanted by the ingenious Scammell Mechanical Horse. Readers over sixty-five may still have vivid memories of these compact, three-wheeled articulated lorries, which seemed able to find a path down the narrowest of streets.

John Hose, who lived not far from the depot, and knew it well from the 1930s to the 1960s, remembers one technique employed by the men who drove the horse-drawn drays. After leaving via the entrance in Newark Street, they would turn the comer into the steep slope at the bottom end of Lower Eldon Street. Here, in order to slow the vehicles as they went down the hill, they would steer to the nearside of the road, and use the kerb as a brake, with the drays’ wheels literally grinding along the kerb’s edge. He recalls that the profile of the kerbstones bore evidence of this treatment.

An aerial photograph of Sneinton taken in April 1923 formed the subject of an article in Sneinton Magazine 61. This view, which is well worth seeking out, included the station, which still bore the painted sign ‘London & North Western Railway Goods Depot,’ although it had since the beginning of that year been part of the new London Midland & Scottish Railway. The warehouse was in its original condition, with double-gabled end walls. Visible in the goods yard were about seventy wagons, with timber apparently the commodity being mainly dealt with. There was no sign of the heated banana vans which regularly arrived at Manvers Street by express goods trains, usually travelling at night. These might, of course, have been inside the warehouse.

Occasional reminders of the branch’s existence did appear from time to time. The Nottingham Journal Reference Book, 1934 , for example, informed readers that: ‘In Manvers Street there are the goods and granary premises connected by a loop line with the main line system.’ Although the publicity for the depot must have been welcome, it is hard to understand how it came to be stated that the depot lay on a loop line, when it actually stood at the end of a dead-end half-mile branch.

The warehouse came to grief on the night of 8- 9 May 1941, when Nottingham experienced its worst air raid of the Second World War. In the course of it the Midland Station narrowly escaped a direct hit, but railway installations a short distance away were not so fortunate. The LMS carriage sheds and rolling stock sidings at Eastcroft were hit, the sheds being totally wrecked, with almost 100 carriages destroyed or damaged. At London Road Low Level one of the goods warehouses caught fire, and the signal box in the yard lost its windows. The old Suburban Railway embankment east of Trent Lane was breached (never to be reinstated,) while the former Midland line had a near miss.

On the south side of Sneinton Hermitage, two arches of the viaduct carrying the Grantham line into London Road High Level station were destroyed. John Hose (son of a railwayman) relates that these were rebuilt almost immediately, and that the viaduct was usable again within a few days; the replacement spans were distinguishable from the originals by having metal railings instead of brick parapets.

Manvers Street was in the thick of the action. Nearby factories and commercial premises were gutted, part of the Boots complex in Island Street, and I. & R. Morley’s huge factory in Manvers Street (next-door to the goods depot) being very severely damaged. As is still well- remembered locally, the Co-op bakery in Meadow Lane received a direct hit, with the loss of almost fifty lives.

Other Sneinton casualties included St Christopher’s church, which was entirely gutted, as were the Trent Navigation premises in Meadow Lane. The Sneinton Dale area received several direct hits, with the school in Edale Road being burnt out. The New Inn in Sneinton Road was substantially damaged, and the Stadium Hotel, just in front of the Ice Stadium and only some three years old, was ruined.

The Manvers Street goods warehouse was almost totally burned-out. Its roof and top floor were destroyed, and with them the entire contents of the warehouse, which included a substantial number of wagons. The warehouse was rebuilt without its top floor; an incongruous flat roof meant that the building never regained its former proportions or the simple dignity which many nineteenth century industrial buildings possessed.

In January 1948 came Nationalization of the railways, and Manvers Street Station, still not quite sixty years old, acquired its third owner: British Railways. The LMS, like the London & North Western a quarter of a century earlier, had ceased to exist.

It was at about this time that I first became aware of the station. My aunt and uncle lived in Manor Street, and from my home in Forest Fields we used to visit them by the no. 44 trolleybus. From the bus stop at the bottom of Lees Hill Footway we would walk up that atmospheric byway of Sneinton; part steps, part steep path, with a group of little cottages halfway up.

And, of course, there was the goods depot, hidden from the Footway by a high wall, but with noises off indicating interesting activity. At the top, in Lees Hill Street, was a tall fence, too high for me to see over. Here I would be helped up on to a conveniently sited fire hydrant marker, from where I was able to see over the fence into the station.

There was usually plenty going on in the goods yard, with a fair complement of wagons being loaded or unloaded. Only once, though, did I see an engine in steam here, and that was during my teens, long after I had ceased to need a lift-up. One warm summer afternoon, I looked over the fence without much real expectation, and was greatly pleased and surprised to find an old Midland tank engine of the type we called Jinties.

As already noted, mention of Manvers Street Station tended to become less and less prominent in brochures and guidebooks. In Nottingham Official Handbooks issued just before and after the war it was now listed among the secondary depots of the city: ‘The LMS Company has other depots in Manvers Street, Lenton, and Radford, which are equipped to deal with all kinds of goods and coal traffic. There is...an electric hoist at Manvers Street.’

In 1960 a booklet called Introducing British Railways Nottingham was circulated in the city. Its main purpose was to inform Nottingham traders of the rail freight services available to them here. No fewer than nine goods depots were still operating at this date. At the three principal ones, Carrington Street, London Road, and Queen’s Walk, a wide range of facilities and services existed. These included the movement of goods sundries, livestock, traffic for bonded stores, loading crane power from ten to twenty tons; and scope for wagon-loads of goods, mineral, and coal traffic.

At most of the smaller depots - Radford, Basford Vernon, Bulwell Market, Basford North, and New Basford - full wagon-loads of goods, mineral and coal-class traffic were dealt with. The only facilities cited for Manvers Street, however, were ‘storage and warehousing.’ Perhaps it is only the benefit of hindsight that leads one to feel that the writing was already on the wall for the depot. The fact that Manvers Street was one of only two in the town to have no goods agent or chief clerk mentioned in the booklet, though, does suggest some decline in status. To contact the depot, an enquirer had to ring the Carrington Street switchboard and ask for Extension 20.

The nineteen-sixties were to bring unimagined and unprecedented changes to the British railway system. The Beeching Report suggested withdrawal of about 250 passenger train services, and the abolition of some 2,000 passenger stations. The Nottingham area witnessed a drastic reduction in the network, among which the most dramatic feature was the rundown and closure of the old Great Central line and Victoria Station. These passenger service cuts naturally seized the headlines all over the country, as they did in Nottingham, but reductions in goods services were just as radical.

Beeching proposed that the railways concentrate on what they could do best with freight: developing train load rather than wagon-load traffic, targeting freight services on a much smaller number of concentration depots: developing private sidings: and creating what became the Freightliner service.

Some idea of the trend of the time can be gained from the figures. Although there had been 6,400 freight depots in 1946, these had already dwindled to 5,200 by 1962. By 1968 there would be fewer than a thousand, and by 1975 even this number had been halved to 500.

In such a climate it was inevitable that establishments like Manvers Street Station should have no future. The end of Sneinton’s goods branch was no more than the loss of a very small pebble on an enormous beach. It came on 6 June 1966, after an active life of only 78 years. As far a can be seen, the local press did not in any way mark the closing day of the station.

So ended the noise of railway activity at Manvers Street, which had lulled many local lads to sleep over the years. John Hose’s final recollection in this account is of listening to the sound of night-time shunting here and in the Great Northern yards at London Road. The familiar rattle and clink-clink-clink of wagons being loose shunted would be regularly punctuated by the exhaust of a labouring engine as it pushed a rake of vans up the sharp incline from the Low Level goods yard up towards Trent Lane Junction.

Having lived off Sneinton Dale at the time, I wish I had taken a closer interest in the depot in its last years. I never photographed it, perhaps not even being aware of its impending closure. As it was, I visited the depot just once, when ordering a new dustbin from A.E. Bott, the builders’ merchants, who then occupied one of the buildings just inside the Newark Street gate. I would have been very surprised if anyone had told me that forty years later I would be writing about the place.

In addition to Botts, other local businesses had rented premises in the goods yard during its years of LMS and British Railways ownership. At various times these had included Arthur Murfet, machinery merchant: Hodson’s Timber Co. Ltd.: and Jackson Gemmell, rag merchant.

Some of the physical features of the branch did not long survive its closure. The iron girder bridge leading into the station over the Hermitage was dismantled in January 1968, and the masonry bridge crossing Meadow Lane was taken down at about the same time.

The work carried out in the 1880s in levelling the rock for the building of the station had provided an excellent flat expanse for new development. Following clearance of the remains of the goods station, the modem housing in Newark Crescent occupied the site by 1969. The present entrance to the Crescent is just where road traffic used to turn into the goods yard from Newark Street.

Other engineering works took longer to disappear, but subsequent decades have seen the removal of virtually all the embankments, and the building of many more houses along the route. Even 25 years ago some local residents were unaware that a station had ever existed here, and the number who remember it must now be considerably fewer, in spite of the clues which still survive to remind one that a railway once ran here.

It is worth trying to trace the course of the line today, and this can be achieved by a leisurely stroll of no more than half-an-hour. The logical place to start is where the Manvers Street Branch began, at Trent Lane Junction. Choosing a fine day, when conditions underfoot are dry, walk up the path on to the Sneinton Greenway at Trent Lane, and pass on your left the remains of the bridge which formerly carried the Great Northern line from Grantham into Nottingham. A few yards further on, above the Greenway Community Centre, it is just possible to trace through the undergrowth the widening of the embankment where the branch left the main line at Trent Lane Junction. From the grounds of the Community Centre below (formerly Trickett's Yard,) a stretch of the embankment’s fine blue brick retaining wall is visible; this, too, bears off at an angle, following the course of the branch. Just before the blue bricks change direction is a straight section of masonry; above this, on the embankment, once stood Trent Lane Junction signal box.

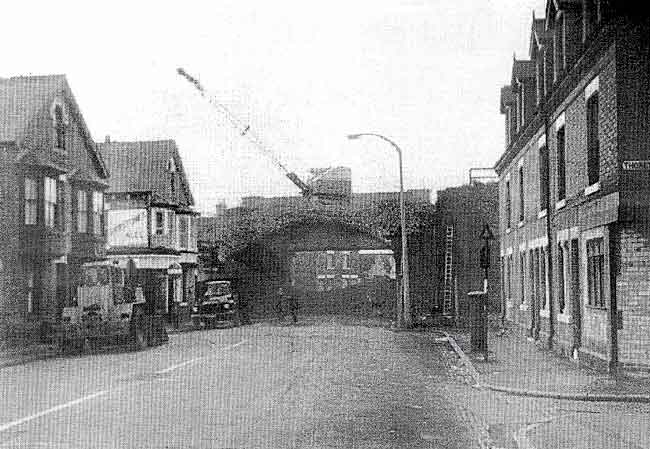

Demolition of the Meadow Lane masonry bridge on the Manvers Street branch, c. 1968. The off-licence on the left is at the corner of Lindum Grove. (Photo: Anne Day collection).

Demolition of the Meadow Lane masonry bridge on the Manvers Street branch, c. 1968. The off-licence on the left is at the corner of Lindum Grove. (Photo: Anne Day collection).The remains of the embankment run along the south side of Radboume Road, but are very soon cut off short. Nothing further survives of this major feature of the branch. The length to the east of Meadow Lane was removed to make room for the laying out of Ivatt Drive. On the west side of Meadow Lane, recent development in and around Gresley Drive has obliterated every trace of the embankment which once loomed over the immediate neighbourhood, and anyone not in the know might never suspect that a railway had once existed here.

There are much clearer traces of the girder bridge which crossed the Hermitage at a sharp angle, carrying the line into the goods yard. On the south side of the road is the wide gap formerly filled by the bridge abutment and adjacent railway land, and across the road the other massive blue brick abutment still exists. Its size demonstrates how very wide the bridge was; spacious enough, in fact, for four tracks and a couple of sets of points above the roadway. The abutment bore until recently a mural representing aspects of Sneinton’s history. It is a great pity that this once attractive feature was allowed to deteriorate to such an extent that its faded remains were removed late in 2005.

The girder bridge which spanned Sneinton Hermitage, in the course of being dismantled. The goods yard was on the left, above the shacks which concealed the entrance to the cave later dug out by members of the Sneinton Environmental Society. The unusual width of the bridge can be seen, and the gents’ lavatory beyond it. (Photo: Anne Day Collection).

The girder bridge which spanned Sneinton Hermitage, in the course of being dismantled. The goods yard was on the left, above the shacks which concealed the entrance to the cave later dug out by members of the Sneinton Environmental Society. The unusual width of the bridge can be seen, and the gents’ lavatory beyond it. (Photo: Anne Day Collection).As you walk from Sneinton Hermitage towards Manvers Street, the railway-related infrastructure is unmistakeable and still dominant. Immediately next to the bridge is a bit of the sandstone rock face, and more blue brick retaining wall of splendid quality. Here too, behind iron gates which once stood at the top entrance to Sneinton churchyard, lies the entrance to a cave. Formerly the back premises of one of the Hermitage rock houses, this was excavated in the 1980s by members of Sneinton Environmental Society, and for some years after was open to the public on guided walks.

The towering Bulwell stone wall already referred to, put up about 1898 by the Great Northern when the Hermitage roadway was moved, follows the curve of the street, rising to well over forty feet at its highest point. It appears still to be in good condition. Beyond this a further stretch of sandstone cliff is exposed, followed by the steeply sloping blue brick retaining wall of what was once the way up to the station’s cattle dock.

Here the Manvers Street entrance to the old station is reached. The inclined access road to the warehouse basement now winds beneath the houses and garages which have taken the place of the sidings. It now accommodates the premises of ‘99 Manvers Street, Surplus Stores Warehouse.’ From the entrance to this access road it is possible to peer in and admire the impressive iron girder and brick construction of its roof.

Climbing the slope to the site of the cattle pens, the walker arrives in Newark Crescent, and is now standing where the goods yard itself used to be. Here can be seen ranges of blue brick retaining wall on the Lees Hill Footway boundary, and an expanse of sandstone cliff, whose height gives some idea of how much rock was cut away when the station was built 120 years ago.

This short tour of what remains of the branch ends with a stretch of retaining wall in Lees Hill Street, and another, about 25 yards long, at the bottom of Lees Hill Footway. The view from Lees Hill Street down to Newark Crescent is instructive; in the street you are standing on the original height of the Hermitage Rock, while the houses below are at the level to which it was reduced for the building of Manvers Street Station.

These vestiges of the branch may amount to no more than a minor railway monument, but even so they deserve to be recognized and appreciated. If nothing else, they help us understand how this small piece of urban Nottingham took shape.

Although it is hard now to envisage the existence of a railway ‘just behind Sneinton church,’ this is not a bad description of it. From the nearest siding in the goods yard to the churchyard wall was a distance of only about 85 yards. My friend’s grandfather, whose comment began this short account, had got it just about right.

Dave Ablitt and John Hose have read this article in draft, and have made valuable suggestions and comments. My best thanks go to them both. Any errors are, of course, entirely my responsibility.

I am also very grateful to Bill Vincent, who kindly allowed the reproduction, at the head of Part 1 of this article, of his fine drawing of the remains of Manvers Street Station. This first appeared in Sneinton Magazine no. 3.

< Previous