< Previous

The Useful Life of JOHN POTCHETT

Part 2: Reduced tradesman and literary character

By Stephen Best

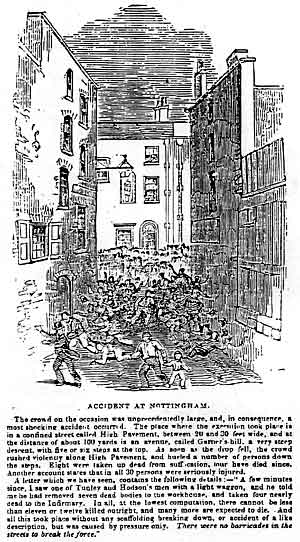

THE DISASTROUS STAMPEDE which followed the hanging of William Saville outside the Shire Hall, as depicted in the Illustrated London News of August 1844.

THE DISASTROUS STAMPEDE which followed the hanging of William Saville outside the Shire Hall, as depicted in the Illustrated London News of August 1844.Part One of this article dealt with John Potchett’s school in Sneinton, his appointment as librarian at Nottingham Mechanics’ Institution, and his series of newspaper letters on the education of the working classes. Part Two takes up the account in the summer of 1844.

NOTTINGHAM’S MAJOR SENSATION OF 1844 was occasioned by William Saville, who on 21 May murdered his wife and three children in Colwick Woods. Saville’s trial began on 27 July, and following an inevitable verdict of guilty he was hanged outside the Shire Hall in High Pavement on 8 August.

This was the most appalling public execution in Nottingham’s history. The crowd of onlookers panicked, owing to the huge crush of people in the street, and twelve of them were killed. The eldest of these was 23, and eight were aged 14 or under.

Scanning the Review for John Potchett’s letters on education (described in part one) brought to light a further letter by him to the editors, in which he argued passionately for the abolition of capital punishment. Not just for the ending of public hangings, be it noticed, but of all executions. The Nottingham Review was certainly the local newspaper most sympathetic to Potchett’s viewpoint, but the letter is nevertheless noteworthy. In it he made no specific mention of Saville or his trial, but observed that ‘the late unfortunate catastrophe' concentrated the mind on the whole principle of capital punishment. John Potchett wrote that he could no longer withhold his indignation over ‘the monstrous anomalies existing between Christianity and the practice of Christian professors in reference to our criminal code.’

He believed that the ending of hangings would bring honour upon the reign of Queen Victoria, and countered the justification put forward by many people that this was the law of Moses as set out in the Old Testament. ‘Are we as Christians,' he asked, ‘to be bound by the law of Moses or of Christ?’

With what one has come to recognize as typical Potchett tenacity, he argued as follows: ‘Now if we are to place ourselves under the laws of Moses, we ought also to build cities of refuge; it will also be required of us that not only murderers shall be punished with death, but also adulterers - disobedient children - Sabbath-breakers - man-stealers, and others, where the law is equally binding as for murder.’

Sadly for John Potchett, he would not live even to see the end of public executions, let alone the abolition of capital punishment, which would continue for over a century after his death.

It appears that the Sneinton premises in Eyre Street did eventually become too small to accommodate Potchett’s school, as the directory for 1848, published by Lascelles & Hagar, listed it at an address in Barker Gate, just two or three hundred yards from Eyre Street. Potchett’s house was now stated to be in Sneinton Road, but this is likely to have been uncertainty on the part of the directory compiler; three years later, at the time of the 1851 census, the family was still living in Eyre Street at (I believe) its corner with Sneinton Road.

This census was the first to provide details of exact ages, family relationships, and places of birth. In doing so it clarified some facts about the Potchetts, but muddied the water in other respects. We leam, however, that they were a Yorkshire family, and more particularly an East Riding one.

The task of deciphering the entries is made harder by the abysmal handwriting of the enumerators who wrote up the Potchett household in three successive censuses, 1841, 51 and 61. Very often enumerators had to do their best in trying to make sense of unreadable details provided by the head of family. In John Potchett’s case, however, this was not the case. As will be attested in a moment, his hand, as befitted a schoolmaster who taught writing, was perfectly legible and clear.

So we shall blame the enumerators, whose efforts were so wayward that Potchett’s name is correctly interpreted in the index of only one census out of the three. On one occasion he is indexed as 'Petchell' and on another as 'Patchett.'

In 1851 John Potchett was 64, and his birthplace was given as 'Rayinham' in the East Riding. There is, however, no such place, and this seemed to be a probable misreading of Keyingham, a village nine or ten miles south- east of Hull, on the road to Spurn Head. Remaining very active, Potchett described himself as 'Schoolmaster; and Librarian to Nottm. Mech. Inst.' His wife Nanny, ten years his junior and a native of Hull, was listed as 'Schoolmaster’s wife.' The three eldest daughters, Eliza, 36: Mary, 34: and Jane, 33, had all been bom at Hedon a market town between Hull and Hedon. Jane was now working as a lace dresser. (Further investigation would confirm that John Potchet [sic], son of Robert, was baptized at Keyingham on 18 February 1787, and that his wife’s maiden name was Akam, presumably a local variant of Acomb or Acombe.)

The next two children were John (31) and Sabina (26), both, like their mother, born in Hull. Charles was now 15, and a cork-cutter’s apprentice. His status in the family was given as grandson, but it is not evident who his parents were. John Potchett’s sister-in-law Elizabeth Laverick completed the household.

This is our last glimpse of the Potchett clan at Eyre Street. By the time of the following census this large family had evidently scattered. In describing John Potchett’s next home address, another name must be introduced to the story. This is George Gill, another of Nottingham’s forgotten great men of the 19th century.

He was born in 1778 at Wilford, where his father was both curate and schoolmaster. Apprenticed to a hosier, he had by the age of twenty become a successful commission agent in the textile trades. Increasingly prominent in municipal affairs, George Gill was Sheriff of Nottingham in 1816. Although the son of an Anglican clergyman, Gill’s religious life took a different turn. As the local historian Robert Mellors remembered many years later, he 'was connected with High Pavement Chapel, but in his old age becoming stone deaf, he attended the meetings of the Friends for the sake of quietness, and not being troubled with books.'7

Gill was interested in education, temperance, the sick, and care of the aged, and made major contributions to the town in all these spheres. First, he was anxious that those who had already left school should have access to higher education at affordable costs. He accordingly bought land in what became College Street, and promoted a public subscription for the building there in 1836 of the People’s College. George Gill contributed about £3,000 from his own pocket towards this. White’s 1864 directory said of the college: 'The design of the projectors was to afford superior instruction for the working classes. The college is open jo all persons, without regard to their religious or political tenets.'

For many working men, the public house was the only leisure amenity, so Gill determined to provide social surroundings that would not involve drinking. He purchased a house in Beck Lane (now Heathcote Street) which had housed the School of Design, and converted it into the People’s Hall, opened in 1854. Intended by Gill to be run on non-denominational Christian lines, it originally provided a library, reading room, news and lecture rooms. Evening classes (on separate days) were provided for men and women aged between 14 and 30. Many clubs and associations met there, and other facilities, such as billiards, became available. Somehow, this splendid venture did not become quite as prominent in Nottingham as might have been expected.

Just before the opening of the People’s Hall, and very significantly for John Potchett, George Gill endowed a block of almshouse dwellings in Plantagenet Street, not far from the rapidly developing St Ann’s Well Road, and the newly- envisaged Sneinton Market. The Working Man’s Retreat was built during 1852-53, and described by Wylie8 as ‘six neat and commodious dwelling-houses...for working men, 60 years of age and upwards, who are not paupers nor have been paupers for five years. ’

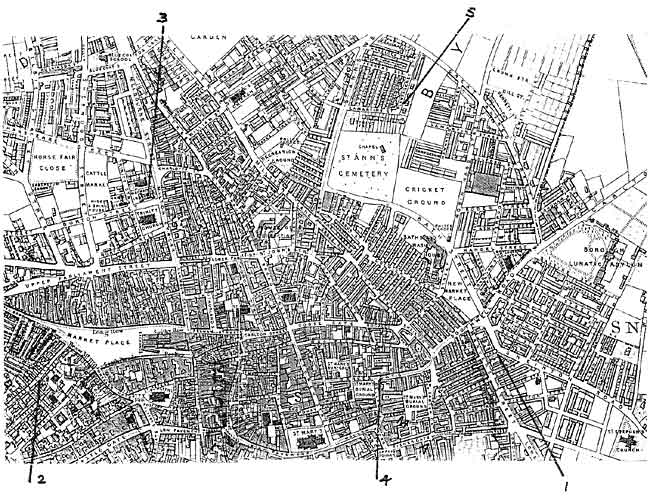

NOTTINGHAM IN THE 1850s, showing five locations associated with John Potchett:

NOTTINGHAM IN THE 1850s, showing five locations associated with John Potchett:1. Eyre Street, scene of his first school.

2. St James’s Street, where the Nottingham Mechanics' Institution first had premises.

3. Milton Street, home of the Mechanics ‘ from 1845.

4. Barker Gate, where Potchett had a school in 1848.

5. Plantagenet Street, where Potchett ended his days at the Working Man's Retreat.

Its foundation deed went into more detail. The Retreat was built ‘For the reception and occupation of Aged People of the working - classes, who are not paupers ...and that the objects of such charity shall be Married men or Widowers of that age of Sixty Years or upwards ...and that such objects shall be of good moral character and be possessed of ...four shillings by the week at least, but not more than ten shillings a week.’

This little block is still in existence, owing its survival to a bit of good fortune. With the redevelopment of the St Ann’s area, each occupant of the Retreat who moved out or died left behind a dwelling that remained empty and abandoned. Vandalism followed, and the trustees of the charity who administered the Retreat possessed inadequate funds for its improvement. Then, in the late 1970s, the building came to the notice of Nottingham Community Housing Association, who acquired it on a 150-year lease. In the 1980s the Working Man’s Retreat was renovated into modem self-contained homes, and is now used for general family housing.

Given today’s negative public image of St Ann’s, anyone visiting Plantagenet Street for the first time might be agreeably surprised, as I was in the autumn of 2005 when revisiting it to take photographs. In addition to the Retreat, several attractive Victorian villas remain, with one or two more around the comer in Lamartine Street. From this street it is possible to walk through into Victoria Park by way of a couple of pleasant nineteenth-century terraces, some of whose houses have cared-for front gardens.

Of brick, with stone dressings, the Working Man’s Retreat can be distinguished from its neighbours by a simple central pediment, within which is a carved stone panel bearing its name. At ground level the frontage is punctuated by three arched entrances, with big keystones, each giving access to the front doors of two of the dwellings. The windows are well-proportioned, with shaped lintels, but the original glazing bars have unfortunately had to be replaced. The chimneys, too, have been simplified. The block is screened from the street by its original high stone wall, with taller gate piers. The rear elevation of the Retreat is much humbler.

Within a few years of its erection, the building was being frequently referred to in print as the Working Men’s Retreat, and is often so called today. The real name, however, is there for all to see on the inscription.

We return to the 1850s, and to George Gill, founder of the charity. He personally selected the first six tenants for the Retreat, and as Robert Mellors wrote many years later: 'Good old John Potchett, a worn out schoolmaster, who as Librarian at the Mechanics Hall was of great service to young men, was one of the first participants in the benefit.’9

Born in 1835, Mellors had clear memories of the 1850s, when Potchett was still engaged at the Mechanics’ Library. Potchett was just the kind of man to command the respect of Robert Mellors. The latter was founder of a successful firm of accountants, director of a number of companies, lay-preacher, temperance advocate, and eventually a county alderman. As already mentioned, he was also a local historian, writing several very useful books on aspects of Nottingham and Nottinghamshire.

John Potchett’s work as schoolmaster, librarian and lecturer must also have found an admirer in George Gill. Although teaching and librarianship have now long enjoyed the status of professions, it is highly unlikely that John Potchett possessed written qualifications as a teacher, and certain that he had none as a librarian. He would, I daresay, nonetheless have had a realistic sense of his own worth, and would have been aware that he was held in considerable respect in Nottingham. What, then, would he have thought of living in a place dedicated to aged persons of the working classes?

Well, we are about to find out, and in Potchett’s own words. Sometimes, when researching a local history topic, a fact or detail expected to give no difficulty stubbornly remains undiscovered. At other times an unhoped-for bit of the jigsaw falls into place as if by magic. This proved to be one of those lucky occasions. A card in one of the name indexes at Nottinghamshire Archives showed a reference to John Potchett for the year 1855: what could this be?

It was nothing less than a letter from Potchett which has remarkably survived, dated October 1855, and addressed to his nephew in Hull. In it we find John Potchett recently settled in his new home at the Working Man’s Retreat, and bursting to tell someone all about it.10

‘Dear Nephew, It is now a long time since I wrote to, or received a letter from you. Tis true , a Mr Somebody called on his way to Colwick, an organist or a pianoforte maker, and said he had seen you and was desired to let us know you were well... You will have heard that we had got appointed to a house, rent free, for both our lives, so that luck has for once taken a turn in our favour. There are six good houses lately built by a Mr Gill, who is still living, and to whom I am indebted for the Centre house, there being to each two good rooms on the ground floor and three capital Chambers, with ashpit and other conveniences in the back yard, and an ornamental Flower Garden, 50 yards frontage in a genteel new street, divided into six equal parts, so that I have now become quite a florist. Each house is seperate [sic] and distinct and not connected by any common passage as a Hospital or Alms house; in fact they are genteel residences for Reduced Tradesmen and Literary Characters ...I may as well state that we have been here six months, and that there are five of us, and no children are allowed, except as occasional visitors. I still continue at the Mechanics' Institution as Librarian and feel highly the benefit of the residence both in mind and body - NP and the rest of the family are in tolerable health, Mary among them being much better than formerly, or nearly restored to health.'

Potchett went on to mention how Nottingham trade had been badly affected by the Crimean War, which he believed had hit Hull’s economy less hard. He also discussed the new organ at the Mechanics, Hall, before returning to his own affairs. ‘You will have perceived by the accompanying slip that I have not quite left off scribbling for the press, in fact I am indebted in no small degree to my position in life as Public contributor, for the possession of my present life, and Freehold Estate, consequently gratitude calls upon me to produce an essay now and then on some general Subjects. The one enclosed, though no. 1 on the ‘Rights of Man,’ is the seventh of the present series... Yr Affectionate Uncle, John Potchett. ’

A postscript shed an interesting light on contemporary happenings on the other side of the world, where a relation, Harry Potchett, was engaged as one of a detachment sent to quell rioting at the Ballarat gold-diggings in Australia. Harry had had a narrow escape when a bullet grazed his head. Potchett closed the letter by mentioning that he no longer had any contact with the family of a man named Robert Harrison. He explained this with the terse comment: ‘They feel above our standard.’

Several points of interest are raised by this letter. Although Potchett went out of his way to emphasize that the Working Man’s Retreat was not an almshouse, it is unlikely that anybody else would have been able to spot the difference. He also stated quite specifically that he had been living there for six months, that is, since the spring of 1855. It seems likely, therefore, that John Potchett may have been a very early occupant of the Retreat, rather than one of the original six. For him to have been in this very first group would mean that there was a very long delay in choosing and installing the tenants.

He also suggested that his activities as a ‘public contributor’ had played a considerable part in gaining for him a place in the Retreat. Presumably George Gill had approved of his lectures and his newspaper pieces.

To give some idea of the kind of man who was admitted to the Retreat, it may be noted that in 1861 his fellow-occupants were a clerk to a silk throwster: three lace makers (past or present): and a man who received a ‘small annuity.’ The annuity would, like Potchett’s, have had to be pretty modest for this gentleman to qualify for a home here.

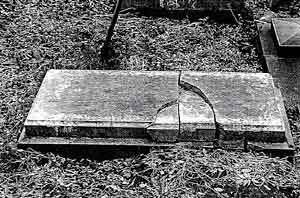

GEORGE GILL’s GRAVESTONE in Nottingham Cemetery. Photographed in 1987, it is now in an even worse plight. (Stephen Best)

GEORGE GILL’s GRAVESTONE in Nottingham Cemetery. Photographed in 1987, it is now in an even worse plight. (Stephen Best)George Gill was, as correctly stated by Potchett in his letter, still living, but died only six weeks later, on 30 November 1855. In 1854 he had seen Gill Street, between Peel Street and Dryden Street, named after him, and had also received a vote of thanks from the Council in acknowledgment of his benefactions to Nottingham. Gill was buried in the General Cemetery, the graveside address being given by Potchett’s old lecturing colleague, the Rev. Benjamin Carpenter. His very plain, flat gravestone has unhappily fallen into a state of near-ruin.

Although he had given up his school sometime between 1848 and 1853, John Potchett’s work at the Mechanics’ Library was to continue until 1861, when he was 74 or 75. The minute books reveal that his final weeks there were marred by an unfortunate incident. On 3 September it was noted that the sum of £2.10.0d had been stolen from Potchett’s desk, and that after ten days the boys who was employed in the library had confessed to the theft. The money had been returned, and the boy dismissed; a letter had been sent to his parents explaining why he had lost his job.

Just three weeks later, the committee proposed that: ‘an annuity of £20 to be paid to Mr Potchett, who was rendered by age and infirmities incapable of discharging his duties.’ This was dependent on the annual general meeting approving the committee decision, which it duly did. John Potchett wrote to the committee, who had also made him an honorary life member of the library.

THE WORKING MAN’S RETREAT as it appeared in the autumn of 2005. (Stephen Best).

THE WORKING MAN’S RETREAT as it appeared in the autumn of 2005. (Stephen Best).Meanwhile, the position of George Hall, the resident librarian whose arrival at the Mechanics’ had been so widely resented seventeen years earlier, was under discussion. The minute book noted that, owing to great difficulties in separating the post of resident librarian from that of the person responsible for cleaning the premises, Hall was to continue in his present post for a further year. Perhaps feeling the strain, Hall had asked the committee for a character testimonial to submit to the trustees of the Working Man’s Retreat, where he too wished to apply for a house.

The Potchett menage recorded at the Retreat in 1861 was much reduced in size from that at Eyre Street a decade earlier. The census found John still describing himself as 'Librarian, Mechanics Inst.' (as he would be until the latter part of the year,) but he was now listed as a widower. On this occasion he gave his birthplace as Holderness ; one of the old wapentakes of the East Riding, this includes, among other places, Keyingham and Hedon. Living with Potchett in Plantagenet Street were now just two people. His 36 year-old daughter, Sabina, now Mrs Good, was his housekeeper.

(Her birthplace was now recorded as Keyingham, although ten years earlier it had been given as Hull.) Sabina’s husband Robert Good, a shoemaker aged 28, completed the household.

Of the other Potchetts who were living at Eyre Street in 1851, just two have been found in the 1861 census for Nottingham and its surrounding area. These were living almost within hailing distance of each other, just a ten minute walk away from Sneinton. Now 41, John Potchett junior lived with his wife and two daughters at his mother-in-law’s house in Edward Street, which ran off Castle Road, almost opposite the entrance to Brewhouse Yard. He was now employed as ‘porter in framesmith’s shop.’ The 26 year-old Charles Potchett had given up cork-cutting, and was working as a railway porter. He, his wife and two small children were at Brewitt’s Yard off Albion Street. This little street still exists, though long bereft of houses, and runs between Canal Street and Greyfriar Gate.

Sadly, John Potchett did not enjoy his Mechanics’ annuity for long. He died at home in the Working Man’s retreat on 15 April 1862, aged 75. His death certificate gave his occupation as ‘Librarian at the Mechanics’ Institution,’ and the cause of death as senectus (old age) and chronic bronchitis. The informant was his daughter Sabina, who had been present at his death. One question is raised by this document. Why did the daughter of a former schoolmaster and librarian who was passionate about education have to make her mark with an X, rather than signing her name? This seems very odd.

The news of John Potchett’s death was received with respectful notices in the Nottingham press. These provide further valuable facts about his life, interspersed with some biographical details which are incomplete or downright wrong.

First into print was the Nottingham Daily Express of 16 April. After referring to Potchett’s years at the Mechanics’, the report continued: ‘The deceased was, we understand, a native of Hull, where he was apprenticed to a watchmaker, and subsequently went to London to perfect himself in that occupation. In 1822 he removed to Nottingham, and for some years obtained his livelihood by working at the bobbin and carriage trade, which about that time was a most lucrative business. ’

At last we know what brought John Potchett to Nottingham. It was the extraordinary trade boom of the mid-1820s, popularly known as ‘twist-net fever.’ With the lapsing of the patent on John Heathcoat’s adaptation of the stocking frame to lace manufacture, skilled mechanics (like the watch and clock maker we now know Potchett to have been) flooded into Nottingham from Manchester, Sheffield, Birmingham and other large towns to build lace machines for owners here, who could not keep up with the demand for lace. For a few years machine builders and owners, together with the twist hands who worked them, enjoyed fantastic prosperity. Some earned five, even ten pounds a week, but the market was soon swamped with the product, and down came the price.

1822 was the date given in the Express for Potchett’s arrival, but that may be a little too early, as the boom years were 1823-25. His daughter Sabina was bom in Hull in 1825, suggesting that he had at first come to Nottingham without his family, or that his wife had returned north to her own relatives for the birth of her baby.

The Express, in common with other Nottingham papers, then made an inexplicable omission in its account of John Potchett's life. After dealing with his time as a bobbin and carriage maker, it continued: ‘When this branch of trade ceased to offer profitable employment to the artisan, Mr Potchett commenced a school in Barker Gate, which he continued for many years, filling up his time by cleaning and repairing clocks and watches.’

Why all the years he spent as a schoolmaster in Sneinton are not mentioned, one simply cannot say. There can be no doubt about this: all the directories between 1832 and 1844 explicitly listed John Potchett’s school as in Sneinton, some of them specifying the Eyre Street address. At the same time, none of the listings of Nottingham schools during those years included his name. Added to that must be Cropper’s reference to Potchett’s Eyre Street school among his notes on Sneinton. Did the press have very short memories in 1862, with no one remembering that he had been active as a schoolmaster long before setting up in Barker Gate?

The report in the Nottingham Daily Express went on to describe Potchett’s role in the forming of Nottingham Mechanics’ Institution, and his work as librarian there. Relating how he had had to give up the post only a few months before his death, the paper stated: ‘To the great credit of the members...a small weekly allowance was unanimously voted to their old servant, for which he was deeply grateful. He had been gradually sinking for the last two or three months, and breathed his last on Tuesday ...Mr Potchett was a man of not inconsiderable acquirements, especially in the mechanical sciences, and some years ago devoted himself to the diffusion of such knowledge as he possessed among his neighbours and associates. He died at a good old age, much respected by a numerous circle of acquaintances. ’

On the following morning, the Nottingham Journal of 17 April gave similar coverage to the death of the man it described as ‘another of the veteran worthies of Nottingham.' It, too, made the mistake of calling Potchett a native of Hull, and overlooked his Eyre Street academy. The Journal, however, made full acknowledgment of his activities at the Mechanics’: ‘He agitated for the institution of a Mechanics’ Library, for which he was appropriately chosen the first librarian. In this position Mr Potchett endeavoured to give a scientific character to the institution, astronomy being one of his favourite recreations. ’

The report recalled how Potchett had formed a class for the study of the celestial bodies, and had constructed a model demonstrating how the planets went round the sun. Of his last days it stated: ‘For some time past Mr Potchett had been very infirm, but the force of habit was so strong with him that he went every night to the Institution until a few months ago, when his visits ceased from inability to leave his house. The members...some time ago voted a weekly allowance for their old librarian; he had for several years occupied one of the dwellings of the Working Man’s retreat; and with other aids he was enabled to spend the last days of his useful life in comfort. ’

Rather surprisingly the Nottingham Review obituary was the briefest of the three, and made the same curious omissions as the other two. Like them too, it stressed what he had achieved at the Mechanics’. After helping ‘in no slight degree' in its establishment, he had occupied the post of librarian ‘down to the last annual general meeting, when his increasing infirmities compelled him to withdraw, and when the members unanimously expressed their regret at his inability to continue in the post he had filled so well, and voted him an allowance...His long life was devoted to useful pursuits that would benefit the inhabitants of the town in general.’

All this made an appropriate farewell to a man who seems to have been almost universally admired. He had not led a very prosperous or particularly exciting life, and his two occupations in Sneinton and Nottingham had been worthy, but hardly the stuff of adventure stories. Having lived in a fairly humble part of Sneinton, he ended his days in relative ease at the Working Man’s Retreat. It might have been expected that, in later years, his name would be forgotten. But over sixty years after his death, Robert Mellors was still moved to write of him as ‘Good old John Potchetl. ’ That, surely, is a tribute worth having.

REFERENCES

1. Abstract of answers and returns on the state of education in England and Wales. British Parliamentary Papers, 1835

2. In the Department of Manuscripts, University of Nottingham.

3. Nottingham Mechanics’ Institution. History of the Nottingham Mechanics’ Institution 1837-1887. Nottingham, 1887. (By J.A.H. Green and others]

4. Nottingham Archives: DDMI 246/1-2

5. Nottingham Mechanics’ Institution. Fifteen years record: being the history of the Institution from 1912 to 1927. Nottingham, 1928. (In an afterword referring to the recent discovery of the NMI minute books)

6. This form of the place name first appeared in the 13th century, and, as Potchett’s letters show, was still in use in the middle of the Cl9th . If nothing else, it did accurately indicate how ‘Sneinton’ was pronounced.

7. Robert Mellors. Men of Nottingham and Nottinghamshire. Nottingham, 1924.

8. William Howie Wylde. Old and new Nottingham. London and Nottingham , 1853

9. Mellors. Op cit.

10. Nottinghamhire Archives: M24,252

This article is dedicated to George Andrew, and to the memory of David Gerard. Like John Potchett, George has been both librarian and schoolteacher. David, sometime City Librarian of Nottingham, read this article in proof, and said he liked the sound of Potchett.

A third friend, Ken Brand, drew my attention to Potchett's letters on education, and in doing so reminded me that in my desk I had a halffinished file on the man. For any errors in the completed article I am of course solely responsible.

< Previous