The Early English Chancel.

At the close of the 12th century the chancel was again rebuilt, and perhaps the nave as well, though the only remaining evidence of this is the plinth course of the western tower. The chancel was lengthened 10 ft. thus reaching its present dimensions. It is impossible to say if much of the earlier work was incorporated in the new, but it was in effect a new chancel of the early English style of architecture. There were three lancet windows on each side above a string course forming the sill; and a steep pitched roof, covered with stone roofing-tiles, with a corbel table beneath the eaves of an uncommon nebule character, the segmental arches of which are worked to suit the varying lengths of the stones. It still remains on the south, and there are traces of it on the north side.

There were flat square angle buttresses of two stages, of which the south eastern, with two grotesque carved corbels above, is still unaltered; and flat buttresses between each bay, one of which remains on the north side, while the westernmost on the south is just seen imbedded in the east wall of the aisle.

Inside, the chancel walls of local lias-stone were plastered, and a string ran round at the level of the window sills. The floor rose two steps towards the altar, as indicated by portions of the ancient screed for the bedding of the tiles, found at two levels. There was a trefoiled piscina on the south side, traces of which were to be seen when the stones of a later piscina were replaced.

Later in the course of the 13th century, a beautiful little priest's door was inserted in the south wall,1 so close to the the western lancet window, that the internal spring of the arch is only an inch from the lower corner of the window-splay, which is worked on the same stone. It has a roll moulding carried round arch and jambs, the arch having a filleted roll formerly supported by detached angle-shafts with caps. The hood-mould, angle-shafts and plinth of this doorway, have been destroyed on the outside, and the sill has been raised 11 ins.

In connection with this great rebuilding of the church, it may here be mentioned that the rectory of East Bridgford had become annexed, as a prebend, to the "Royal Free Chapel" or Collegiate Church, founded in the castle of Tickhill, Yorks., by Eleanor, wife of Henry II. In 1191-3 this was granted by King John to the Archbishop and Canons of Rouen,2 under the title of "The Chapelry of Blyth, with all its appurtenances namely . . . . . the Church of Brigeford" etc. The new patrons were perhaps well disposed to forward the renovation of their prebendal church, which took place at this period. But we find that King Edward I. again exercised his right of presentation, granting the "free chapel of Tickhill" to John Clavell, who was inducted into the church of "Briggeford," and to Boniface de Saluciis, who succeeded Clavell in 1282.3 It was not, however, to the liberality of a royal foundation that the subsequent alterations in the church are due: in many cases the cause is rather to be found in the instability of its foundations on clay. The whole course of its history has been one of impending disaster, from the fact that the foundations were not laid deep enough, and the four-foot bed of clay above the Keuper marl and sandstone, assisted by numerous interments around the walls, has continually yielded to their weight.

The 14th Century Enlargement.

Early in the 14th century, the advowson of the rectory was claimed by Sir John de Caltoft and Sir John de Multon, the husbands respectively of Agnes and Isabella, co-heiresses after three female successions to John Biset's manor of East Bridgford, and was held alternately by their heirs. In the middle of the century Caltoft's moiety of the manor became Chaworth's, and Multon's moiety4 had passed to the Deyncourts, of Radcliffe. In 1353-4 William Deyncourt gave a messuage with 300 acres of land " for three chaplains to celebrate in the Church of east Bruggeford." (Esc. 27 Ed. III., quoted by Thoroton.) In 1480 this moiety of the manor was bestowed by John Deyncourt on William de Waynflete, Bishop of Winchester, and formed part of the original endowment of his College of St. Mary Magdalen at Oxford. With it, of course, passed the alternate presentation to the Rectory, until in 1838 the college became possessed of the sole patronage.

To return to the history of the building. Under the fostering care of its knightly patrons, an enlargement of the nave was commenced about 1330, first by the addition of a north aisle with an arcade of four bays, having octagonal piers of Gedling stone with moulded caps and bases, and sharply-pointed arches of two plain chamfered orders. The chancel arch, with the peculiarity of a label on the eastern side only, is of the same date, replacing a Norman or Early English arch. A corresponding arcade with its aisle, on the south side, was next built, but the irregular and coarsely-moulded caps show a curious contrast to those on the north side, suggesting the explanation that the work was interrupted by the Black Death in 1349, and continued with inferior mason-craft afterwards.5 Both arcades have labels resting on head-corbels towards the nave; and the southern arcade possesses labels and corbels towards the aisle also.

Transepts were built, but not structurally connected with the nave arcades. I cannot find any evidence that these replaced earlier structures. They have since been destroyed, but the foundation of the south-east angle buttress is now visible on the south side of the church. The south transept was wider than the north, and the corresponding bay of the arcade wider than the others. It may have been extended westwards with a second bay in the following century.

The transepts formed mortuary chapels with altars, and contained three tombs with armour-clad effigies, described by Thoroton. In the north transept was a cross-legged knight, clad in hauberk and hood of plain chain-mail, with long surcoat reaching below the knees, and a pointed shield said by Thoroton to display the arms of Caltoft—Argent, an orle of cinquefoils about a small escutcheon sable. For many years this stone slab served as a buttress to a garden wall at the Hall, but I have been able to replace it, though much mutilated, within the church. On a tomb in the south transept were shields of Deyncourt, Gouzell, D'Arcy, and Hethe impaling Caltoft. (Thoroton's Hist.).

In the north wall is a recess for a founder's tomb with square jambs surmounted by an arch. Thoroton says it bore the name of Johannes Babington, 1409, but the peculiar mouldings of the arch appear to be of an earlier date. A stone shield inserted in the wall above is carved with the arms of Babington—ten roundels with a label of three points.

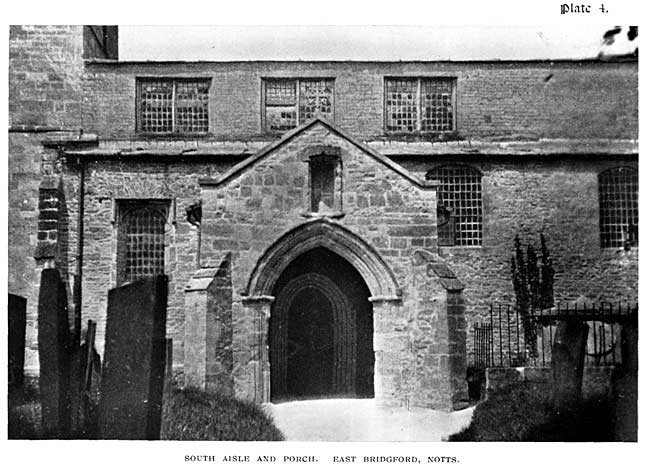

There is a north door to the nave, with a plain chamfered arch, and a hood-mould very rudely reset. The picturesque south porch, with angle buttresses, is of this period. Its outer arch has two orders of wave mould to jambs and arch, and a niche above with ogee arch and embattled cornice. Later alterations to the gable and west side have brought the apex five inches out of centre, thus giving a not unpleasing lack of symmetry to the niche and buttress. (Plate 4.)

In the chancel, the work carried out during the 14th century was probably rendered necessary by the outward settlement of the foundations of the south wall. In consequence of this, the central part of the wall was rebuilt, and its three lancet windows replaced by two large, probably square-headed, Decorated windows of two lights, with a large buttress between them. The internal splays and segmental rear arches of these windows have now been made visible. The chancel was further enriched by a piscina (nearly in the same position as a previous one) and sedilia, with crocketed ogee arches under a continuous horizontal hood-mould, of a very usual midland type. (Plate 6.) The level of the floor was raised and paved with tiles.

A buttress in the angle of the tower and south aisle was at this time rebuilt in similar character to the new buttress on the south of the chancel, no doubt to remedy a like defect in the foundations.

(1) The fact that the lintel of this door is clearly inserted, may be evidence that the wall is that of an older building than the 12th century chancel.

(2) Calendar of Documents preserved in France. J. H. Round. Rolls Publ. 1899.

(3) Thoroton's Antiquities of Nottinghamshire, 1677, p. 151.

(4) See Appendix A.

(5) It has been suggested that the two patrons may have carried out the work independently on the two sides of the nave.