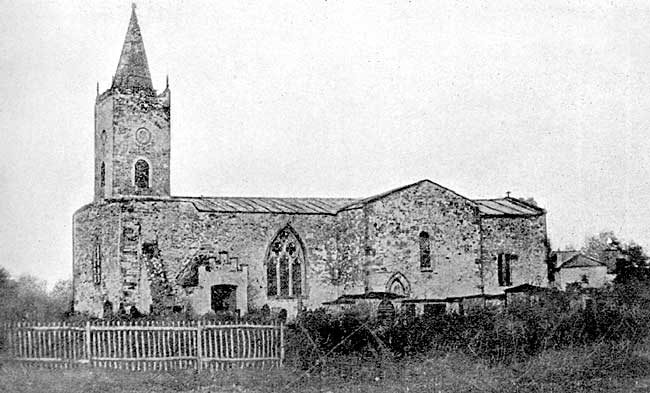

Hoveringham church

BY REV. A. M. Y. BAYLAY

The next place to be visited after Gonalston was Hoveringham, which was soon reached.

Here again the Rev. Atwell Baylay contributed to the interest of the day by giving the following information respecting the church, of which he is vicar, as also of Thurgarton; the united livings being in the gilt of Trinity College, Cambridge.

Hoveringham old church.

The ancient church of S. Michael, Hoveringham, was cruciform, without side-aisles, as may be seen from photographs taken before its destruction. It is doubtful if it originally had a tower. A brick one, however, with a lead spire, had at some time been erected, and contained three bells. In 1865 this interesting building was wantonly and inexcusably destroyed, to make way for the brick church now standing, and the only ancient objects now visible are these: (1) The fine Norman tympanum, formerly over the south door, representing S. Michael defending the Church (figured as a lamb bearing a cross) from the Dragon. At the side are figures of S. Peter and of a bishop with a crozier. It should be compared with the similar tympanum of earlier date, now over a small door inside the north transept, of Southwell Minster, (2) The tomb of Sir Robert Goushill and his wife, formerly in the south transept, of which more anon. It has been shamefully treated by the rebuilders of the church, turned north and south, and actually cut, to cram it into the corner where it now stands. (3) The font has an interesting history. It has certainly not been originally a baptismal font, for it had no water-drain until six years ago. It had also no central support, for the under-side had a boss of ornamental foliage in the centre; so it must have been carried on four slender pillars at the corners. It has undoubtedly been a holy-water stoop, and was evidently never made for a little village church. In all probability what happened was this:—The font having been destroyed by the Parliamentarian troops during the siege of Newark, as was so commonly the case in this district, the Hoveringham people, at the restoration of Charles II., looked about for a substitute, and finding this bowl (of Early English date) among the ruins of Thurgarton Priory, they fitted it on some pieces of Norman work with zig-zag mouldings, and set it up, with a metal bowl inside, to serve as a font. The rebuilders turned it out, and it stood in Mr. Baines’ garden until 1897, when it was restored to its holy use, and a new supporting pillar added; the old support, whatever it was, having perished.

Tympanum, Hoveringham church.

Figures on tympanum, Hoveringham.

It may be added that the present bell is one of the three which were in the old church tower.

On the south side of the church is a portion of the plain octagonal shaft of the Churchyard Cross, which has been at one time utilized as a sun-dial.

The following is the strange and interesting history of Sir Robert Goushill, or Gouxhill, and his wife. The lady Elizabeth Fitzalan was the daughter of Richard Fitzalan, 14th Earl of Arundel, and sister of Thomas Fitzalan, 15th Earl. She was born in 1372. Earl Richard was, along with the Duke of Gloucester and others, accused of high treason in 1397, and beheaded on September 21st, in that year. Among his accusers was Thomas Mowbray, Earl of Nottingham, afterwards created first Duke of Norfolk by the king (Richard II.). Strange to say, the Earl of Arundel’s daughter Elizabeth, whose first husband was William de Montacute, son of William, Earl of Salisbury, was married after his death to this Thomas Mowbray, who was one of her father’s accusers, but whether the marriage was before or after the trial I am not able to state.

On September 16th, 1398, the quarrel between Henry, Duke of Hereford (afterwards Henry IV.) and Thomas Mowbray, Duke of Norfolk, was settled by King Richard II. banishing them both. The Duke of Norfolk nominated as his attorney during his absence, Robert Goushill of Hoveringham, his esquire. The duke did not long survive his banishment, but died at Venice, February 27th, 1400. His widow, some time previous to September 30th, 1401, took as her third husband this same Robert Goushill. King Henry IV. was now on the throne, and Robert Goushill was one of those who fought on his side at the battle of Shrewsbury, Sunday, July 21st, 1403. He is said to have been knighted on that very day. Having been severely wounded in the side he had to quit the field, and laid himself down in an exhausted condition by a hedge. There he was found at night-fall by his servant (who had run away at the very beginning of the fight), whom he asked to relieve him of his heavy armour, arid, in case he should not survive his injuries, to carry to his wife (the Duchess of Norfolk), his last message, together with his purse, his ring, and other valuables. But the cowardly wretch had no sooner stripped his master of his armour than he stabbed him to the heart, and made off with everything of value. It is satisfactory to know that his conduct had been observed by another wounded man who lay near, and that the murderer was caught and hanged.

It was, no doubt, the Duchess who now erected this sumptuous tomb, for her husband, in Hoveringham church, with her effigy beside his. She wears her peeress’ mantle, and ducal coronet. Her husband is in full armour of the period, and has the “orle” or garland round his steel headpiece, which was supposed to relieve the pressure of the heavy tilting helm. This helm is under his head, and bears his crest, a Saracen’s head. To this the old people in the village have been used to point as representing his black servant who murdered him; so that it is evident that some sort of tradition of his tragic death lingered on in the place. It will be noticed that he has taken off one glove, and originally his right hand clasped that of his lady, but the right arms are broken off and gone. The shields on the tomb are said by Thoroton to have been painted with the arms of Leek, Langford, Babington, Chaworth impaling Caltofts, Rempston, and others. In the old church was a stone in memory of Nicolas Goushill, son of Thomas Goushill, which Nicolas died in 1393, on the festival of S. Prisca (January 18th).

There seems to have been two families of gentry in Hoveringham at the same time, the de Hoveringhams and the Goushills. The house of the latter is supposed to have been southward of the church, in the field called the Old Hall Close. Their property eventually came into the possession of the Prior and Canons of Thurgarton, and passed at the dissolution to Trinity College, Cambridge.

It appears doubtful whether the Duchess Elizabeth was after all actually ever buried at Hoveringham beside her murdered spouse. At all events, she had a fourth husband, Gerard Ufflete, a Knight, who fought at Agincourt in 1415. She herself died July 8th, 1425, being then only fifty-three years of age.

Two beautiful decorated three-light windows were made into rock-work for the garden of the house inhabited by the curate, at the time the old church was destroyed. Fifteen years ago they were put together again by the care and skill of the Rev. C. F. G. Turner, and remain in the garden referred to. One was the west window, the other was in the south wall of the nave.

Other remains are in Mr. Baines’ garden at the ferry, viz:—part of’ a cusped arch, an incised tombstone, some pieces of alabaster from the Goushill monuments, &c.

In the garden of a house belonging to Mrs. Baines, senr. are:—an arch which stood over a tomb, the arches of two piscinas, and the stone drain of one of them, the head of a small single-light window, part of the jamb of the chancel arch, two stones from the inner corners of a window-opening which was furnished with angle-shafts, a good specimen of a very early headstone from a grave, &c.

It should be noted that in both the gardens last referred to are many other ancient remains, collected by the late Mr. Babes, some of them stones from Thurgarton Priory, others brought from various “restored” churches in the neighbourhood.

One member of the family of Goushill, mentioned in connection with this church, viz., Sir Thomas de Goushill, must have enjoyed a long life in the days of Edward III., for his son and heir was, at the time of his death, found to be about sixty years of age!

The Goushill arms, according to the seal of Sir Nicholas Gousbill (Rich. II.) were—Barry of six with a canton ermine, and the crest a blackamoor or saracen’s head. Thoroton under Bridgford (p. 153, col. i.) describes them with the tinctures, viz., Barry of six or and gules, a canton ermine, although in the plate of arms he indicates the barry to be or and azure, and the descendants of this family in the present day claim or and azure as correct.

Luncheon was taken at the “Elm Tree,” which stands on the banks of the Trent, and has a pretty outlook upon the wooded hills on the opposite side, in the midst of which the tower of Kneeton (or Kneveton) Church is seen.

Caythorpe having been passed and Gunthorpe Bridge crossed, East Bridgford was approached by a steep and leafy lane from the river level.

The Rev. A. du Boulay Hill assembled the visitors in the church of St. Peter, and proceeded to explain the carried out. As the rector had read a very complete paper on this subject, on the occasion of the Society’s annual meeting in April, no further remarks are needed here. The paper will be found in the supplement to this volume.

In Black’s Guide to Notts., edited by the late A. E. Lawson Lowe, it is stated :— “Near this (E. Bridgford) there was formerly a very important Roman station upon the Fosse road, considered by Stukeley to have been Ad Pontem and so called from the ancient bridge, which lie maintains, once spanned the Trent at this point. Horsley does not coincide in this opinion, but regards this place as the Margidunum of the Sixth Iter of Antoninus, although he does not decide absolutely whether Newark or Southwell occupies the true Ad Pontem. Many facts are to be deduced in favour of the latter theory, which is materially strengthened by the circumstances that no vestiges of an ancient bridge have ever been discovered near the place, nor can any important Roman road be proved to have existed across the Trent valley opposite to East Bridgford, although an undoubted Roman road leading from the Fosse to the banks of the river yet remains. The site of the old Roman station is near the Fosse, about a mile southward of the village and is commonly known as the ‘Borough Field,’ where many interesting Roman antiquities have been found and some remains of the ditch and mound of the camp, now called ‘Castle Hill,’ may be traced.”

Bridgford being left, the road was taken that follows the top of the ridge above the river. At some distance on the right in the valley could be seen the remains of the manor house of Shelford, now a farmhouse. The traces of its former importance are so few and slight that it was not deemed worth while to deviate from the route in order to inspect the site.