The Old Inns of Brewhouse Yard

BY MR. HARRY GILL.

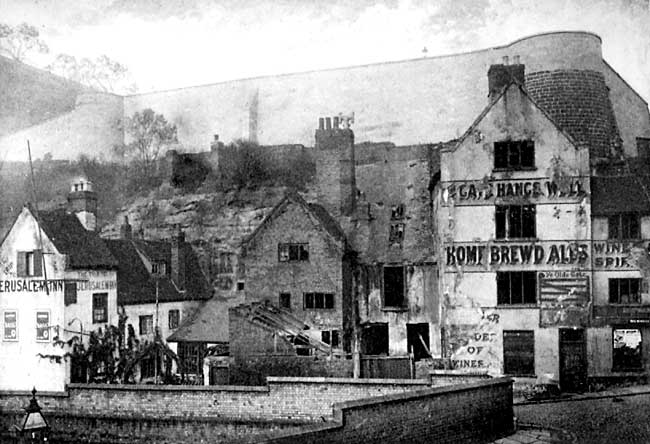

The Gate Hangs Well (on the far right) and Old Trip to Jerusalem (on extreme left), Brewhouse Yard, Nottingham in the 1900s.

Although much has been written about this picturesque and interesting little corner of our City— enough to make some of our members think, and say, that the subject has become barren—there are others I find who do not even know where the place is: so that just at this time, when one of the old Inns—in course of demolition when this paper was being written, and even now (December 15th, 1909), razed to the ground— and when the four adjacent houses are undergoing renovation, in order to convert them into up-to-date tenements, “fitted with electric bells and every modern convenience,” it may not be out of place to give a summary of the history, and to put upon record a brief description of the ancient buildings.

Brewhouse Yard is the name that was given to a piece of land—now in the Parish of Standard Hill, but formerly extra-parochial—a little more than two acres in extent, lying between the Castle rock, and the old bed of the River Leen.

In mediaeval times it was known as the “rock-yard.” It included the caves in the rock, used from the very earliest times as dwellings, and the “chambers” and “offices,” where malting and brewing were carried on. Thoroton (page 490) says “The exactest Survey I find of this Castle, and the Appurtenances to it, is the account of Jeffrey Knyveton, Constable of the Castle, and Clark of the Forest 25. H.6.” This “accompte” is given in extenso in John Hicklin’s “Nottingham Castle” (p. 100) wherein the “rocke-yard” and the “dove-cott” are mentioned. It is probable that the dovecote of the Castle was placed upon the jutting rock, over the lower entrance to Mortimer’s hole, while at the south-eastern extremity of the yard stood the mill of the Castle which used to grind all the corn for the support of the garrison.

Until the reign of James I. this piece of land formed part of the Castle estate; but in A.D. 1621 the Rock-yard and the ground or land round about called Dovecoatclose was sold by the Crown to “Edward Ferres, of London, mercer & Francis Philips, of London, gent., exemplify’d to John Mitten, & William Jackson.” (Deering, p. 175).

There seems to be some uncertainty about the date when the distinctive term “Brewhouse Yard” was first applied, for in the Borough Records, between the years 1610 and 1618, “the Brewhouse,” and “under the Castle,” are used as synonymous terms.

(1) The boundary mark, dated 1869, is at the foot of the Castle rock, between the four messuages and Collins’ houses.

(2) The Dovecoat-close was on the east side of Mansfield Road. Deering probably used the term in connection with this land because of its proximity to the Castle dovecote.

At the time of the sale (1621) the estate was described as “the Brewhouse,” meaning the brewhouse of the old Castle then standing, but in 1643 an assessment was made on “the residents under the Castle.” I think, however, it will be safe to say that the name has been continuously used ever since the time of the Civil War.

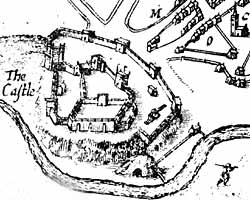

Extract of John Speed's map of Nottingham, published in 1610, showing Brewhouse Yard between the River Leen and the Castle.

The earliest map of the town available for reference is the one issued by John Speede in 1610. Thoroton says (p. 491) “The Scituation of the Town, with the Streets, Lanes, and remarkable places, is most aptly described by John Speed’s Map, to whom I refer those that desire more exactly to know it.” This map shews the chambers in the rock, and but one solitary building standing at the corner of the road leading into “the yard.” Extensive building operations must have been commenced at about this time, for in 1670 another map (bearing no name) was engraved, shewing a long row of tenements on the south side of the roadway; also four detached houses with gardens situate between the long row and the River Leen. Thoroton’s map (1677) is based upon this, but having the buildings set up in “bird’s-eye” perspective, from which it would appear that there were thirteen houses in the long row, but this point is not conclusively shewn. Deering, in his “History,” published in 1751, adopts the map published seven years earlier by Badder and Peet, which shews the addition of two houses on the cliff facing east, a block of four tenements on the north side of the roadway, and two inns near the entrance to the yard, “The Trip to Jerusalem,” and “The Gate.”

The “17 small decayed tenements” (to quote Deering’s description) on the south side of the road, together with all the buildings lying to the south thereof, were cleared away entirely, and the land occupied by the Corporation Water Department, formerly as a pumping station, but now as stores.

I think it is more than probable that one or more of these tenements were converted into inns during, or soon after the Civil War—being a lawless place anybody could brew and sell ale as they liked—and there we must fix the location of “The Wheel,” “The Bottle and Glass,” and “The Junk Ship.”

“The Wheel” was put up for auction in 1785,1 and described as “that well known and good accustomed house, known by the sign of The Wheel, in Brewhouse Yard, near Nottingham.” As this house is not mentioned in Willoughby’s Directory of 1799 it is possible that the name had been changed to the more popular sign of “the Bottle and Glass,” which is stated in the Directory to be in Brewhouse Yard.

The peculiar sign of “the Junk Ship” is contained in an advertisement for recruits, which appeared in the Nottingham Journal, Dec. 8, 1787. “Volunteers for the East Indies . . repair to the Recruiting Officer, at the sign of “the Junk Ship” Brewhouse Yard.”

Mr. William Stevenson says that even in his early days “the yard” was a favourite resort of soldiers, and during the military revolt at the Park Barracks in the forties of last century, the soldiers flocked to these houses and were there arrested as deserters.

(1) To be Sold by Auction

By G. Burbage

on the Premises, on Wednesday, the Eleventh Day of July, 1785, in the following Lots; (if not sold by Private Contract)

Lot 1st That well known and good accustomed House, known by the sign of the Wheel, in Brewhouse Yard, near Nottingham, in the possession of William Clarke— Also the house adjoining in the Tenure of John Wigley Lot 2nd The Public House, situate in said Place, known by the sign of the Pilgrim, in the possession of Widow Footit:—and likewise the house adjoining in the tenure of Ralph Cantrell.

Nottingham Journal. Saturday June 25. 1785.

On Saturday, June 17th, 1786, the following advertisement appeared in the Nottingham Journal:— “Pink Shew / Gentlemen florists / Your Company is desired to dine with the ancient Society of Florists, at Mr. Cheatham’s, The Gibraltar, in Brewhouse Yard, near Nottingham, on Tuesday the 27th June 1786.”

Datestone.

The conspicuous double-gabled house, perched on the rock and facing eastwards, is still locally known as Gibraltar. It is said to have been built by John Collin, who inherited a portion of the Brewhouse Yard estate by his marriage with Mary Langford, daughter of George Langford, who was Mayor of Nottingham, 1687-8. This Alderman John Collin, the father of Langford Collin, was the grandson of the celebrated Lawrence Collin, a gunner (see muster—roll, January, 1648), appointed by Oliver Cromwell to the command of a company doing duty at Nottingham Castle under Colonel Hutchinson during the Civil War. At the conclusion of hostilities he settled down in Nottingham to his former trade of wool-combing. The house in Castle Gate, with the date stone in the gable (see Transactions for 1907, p. 108), was probably built by him, and his monument is in the south aisle of St. Nicholas’ Church. The family became very prosperous: his son, Abel Collin, a wealthy bachelor, caused the very fine block of almshouses in Park Street to be built (1709) and later (1831) the larger and plainer block in Carrington Street was built under the same charity.

Although this house is now without a license, there is every reason to suppose that it is identical with the Gibraltar inn, kept by Mr. Cheatham, in 1786. The great siege of Gibraltar, which lasted from 1779 to 1783, caused several inns which sprang into existence at that period to adopt the sign of the Gibraltar, or the Gibraltar Rock, and its position upon the rock, at the top of a steep flight of steps, renders the name an appropriate one. This house, and a smaller tenement on the north side of it, are now cut off from “the yard,” and approached only from the Lenton Boulevard. At one time the smaller house had a very unenviable reputation; in fact, the whole yard obtained an unsavoury distinction, that was not due to the trades of brewing, tanning and dyeing that were once carried on therein.

The “4 messuages” on the north side of the narrow roadway (10 feet) are the only houses that remain in the yard, which is now enclosed with iron gates. In spite of alterations and repairs, these houses form a very picturesque group, with their red tiled roofs and gabled fronts, rising out of the little fore-courts or gardens, and backed by the precipitous sandstone rock. The sloping foot of the rock had been cut away—probably for strategetical purposes by Colonel Hutchinson during the Civil War—and the houses were built so that the ground floor rooms at the back gave direct access to the chambers” in the rock—to the very chambers in which the progenitors of our race once lived, in which the barley was malted, and the nut-brown ale for the Castle was brewed, and in which the plague-stricken residents of the County were tended (Borough Records, vol. IV., p. 300. A.D. 1611), and these are henceforward to be used as coal-cellars. At the first floor level a lead gutter, two feet wide, is laid on the top of the rock, between the back wall of the houses and the face of the cliff. Although the materials used are so simple and the style so unpretentious, the houses are stamped with a character and picturesqueness that is not found in modern domestic work. The bricks are of a beautiful colour and texture, 9½in. to 10in. long by 2½ft. thick, nine courses rising 2ft. For the sake of comparison, I may say, that in modern work seven courses rise 2ft. The roofing tiles, 10in. long by 7in. wide, are hand-made, and have a very soft and uneven surface. The only architectural embellishments are the flat gauged arches over the windows and doors, having projecting brick key-blocks, and plain string-courses at the floor levels, formed with four courses of bricks projecting 1¾in., which effectually serve to bind the design together. There are no window sills; the windows, formed with 4in. by 3in. moulded oak frames being set on the brickwork 1¾in. back from the face of the wall, and glazed with small squares (6in. by 4½in.) of crown glass in lead cames. The stairs are in oak with square newels, turned balusters and solid strings. The beams supporting the old plaster floors are of oak (16in. by 12in.) roughly adzed on the face and whitewashed. The houses are very characteristic of the early Stuart period, and appear to have been built at the same time as the Ducal Castle (1674-1679) probably for the use of retainers.