The Rev. Edmund Cartwright, D.D

The following diatribe on Antiquarian research, to which his nephew, Edmund Cartwright was at that time seriously turning his attention, will, perhaps, hardly meet with the approval of the Thoroton Society. "As to Antiquarian researches, they may amuse, but they do little towards invigorating the mind, I rather think they have a contrary effect. Genuine science delights to look forward into the unexplored regions of thought, but what is the effect of a turn for antiquarian inquiries? To give a retrograde direction to the mind, leading it back into the ages of ignorance and barbarism, to waste its powers upon objects scarcely worth picking up and preserving, when raked out of their dust and rubbish. I dont mean absolutely to condemn such inquiries—they are well fitted to the moles of mankind, who have not eyes for stronger light than what is adapted to such researches."

But the striking personalities of George and John Cartwright paled before the brilliant genius of their brother, Edmund. Born in 1743, he was early destined for Holy Orders, and in due time was presented with the living of Goadby Marwood. At this time, Edmund Cartwright was well known in literary circles as reviewer and poet : he was a regular contributor to the Monthly Review, and was also known as the author of "Armine and Elvira," of which Sir Walter Scott says, "We need only stop to mention another very beautiful piece of this fanciful kind by Dr. Cartwright, called 'Armine and Elvira,' containing some excellent poetry, expressed with unusual felicity."

In addition to his literary tastes, Edmund Cartwright had a peculiarly enquiring and ingenious turn of mind.

While perpetual curate at Brampton he cured several apparently hopeless cases of putrid fever by the administration of yeast, the practice, in such cases of administering medicine in a state of effervescence being until then unknown. At Goadby Marwood, he devoted himself to agricultural experiments in the cultivation of his little glebe, with the result that in 1805 he received a gold medal from the Board of Agriculture for a prize essay on artificial manures. A visit to Matlock in 1784 was the turning point of his life, to his glory and his ruin. Sir Richard Arkwright had lately invented the Spinning Jenny, and at a public table it was stated that more yarn would be manufactured than could be used by the English weavers. Mr. Cartwright, who was present, suggested machinery for weaving, but was told by the experts from Manchester that such a thing was impossible, owing to the variety of movements required. Nothing daunted, Edmund Cartwright, on his return, essayed the impossible, and in 1785, he brought his invention to such a state of perfection, that he thought it advisable to take out a patent, and to this country clergyman remains for ever the honour of an invention, which has revolutionised the manufactures of the world. An even more wonderful invention was his woolcombing machine in 1789, and amongst other inventions was a steam-engine in 1797, as well as a reaping-machine and even a horseless carriage. His lack of engineering training wassupplied by hisgenius, but, unfortunately for him and his family, his genius fell short when it came to business capacity, and the acquirement of a factory at Doncaster, where he should be able to give scope to his mechanical experiments proved a fatal speculation. In 1791 his power-loom seemed about to meet with the financial success it so richly deserved, for Messrs. Grimshaw, of Manchester, contracted with him for the use of 400 of his looms, and built a mill for their reception. But the triumph was short-lived, for when only twenty-four of the looms had been set to work, the factory was burnt to the ground, and there was no doubt but that the incendiaries were the incensed and frightened hand-loom weavers. The consequences to the inventor were ruinous, his contract with Messrs. Grimshaw became void, and no other manufacturer had the courage to make a fresh attempt. In his later years he found that both his power-loom and woolcombing machine were extensively used, but he never reaped any pecuniary benefit, and after the experiment of one big lawsuit, he found it too expensive to fight even the most flagant cases of infringement of patent. His brothers and sisters, who had perhaps too generously assisted in the promotion of his schemes, and the expenses of the lawsuit, all shared in his ruin, and Marnham had to be sold. Indeed he and his whole family were brought to such poverty, that in 1809 he thankfully accepted a Government grant of £10,000, which afforded him a small competence for his declining years. A letter, hitherto unpublished, to one of his sisters, gives some idea of the dire straits of poverty, to which he was reduced.

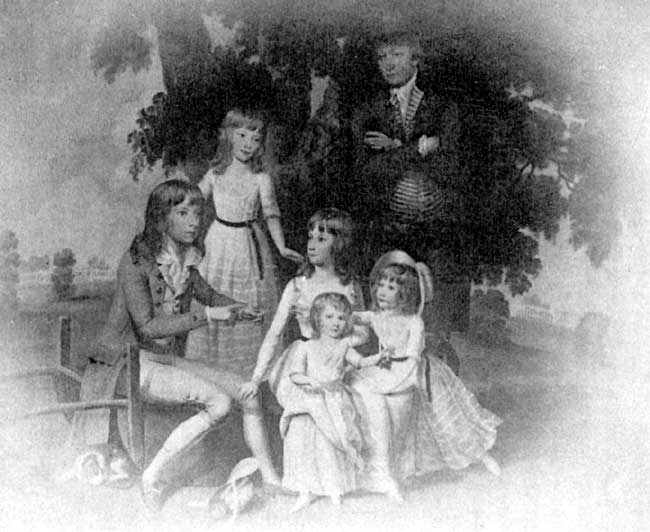

The Rev. Dr. Cartwright and his children. From

a painting by Hawes, 1786.

The Rev. Dr. Cartwright and his children. From

a painting by Hawes, 1786."Dear Sister,

I feel myself much obliged by the ready acquiescence in what has been proposed. From the astonishing depression of property, it is impossible to conjecture the loss that will be sustained by the sale of the Doncaster property. You may however religiously rely on my doing you the most ample justice the moment it is in my power. Indeed your uniform tenderness to me claims every return I can make you. Had I not been cautioned by past events not to be too sanguine in any thing, I have every reason to think that the time is not far off when my unwearied exertions for years past will meet with some remuneration. I have the pleasure to tell you that the non-suit, we suffered in the last trial, has been set aside, and that we have got evidence, which will completely overthrow that part of our adversary's case, which could any way affect us, and which we have reason to think he means to support; our evidence is such however as will be perfectly decisive. Should 1 be so fortunate as to succeed in obtaining the Secretaryship to the Society of Arts, I shall be relieved from my present embarassed situation. By my sisters calling for what is allowed for Anne Catharine, the whole of my income is £55, out of which I have to find board, washing and lodging for Eliza. Should John follow my sisters example respecting Frances, my income would be £30 less. The Salary of the Secretaryship is £150. After I have paid the increase of the income tax by that addition, I shall have no better income than I had before, till Mary withdrew from me, and Anne Catharine's allowance was given up. The only advantage over what I had last year will be the house rent free, and coals and candles. I had a trial of a small steam-engine of mine a few days ago, in the presence of some persons of rank and science, when its power was ascertained to be one-third more than any engine yet known. Its superiority indeed is in every point of view so decided, that I think it impossible it should not take, provided anything of mine is ever to take. I will however hope for the best. Pray, where is my daughter Eliza, I have neither heard of nor from her for this age past. With my best compliments to your kind friends where you are, I am my dear sister, your ever

affectionate Brother

Edmund Cartwright."Nov. 24, 1799.

The public recognition of his genius, which seemed so cruelly denied him during his lifetime, came more than a hundred years later, when in 1904 the Cartwright Memorial Hall was presented to the City of Bradford, "by the late Lord Masham, who paid a touching tribute to the immense debt of gratitude which Manchester and Bradford owed to the ruined inventor of the power-loom and the woolcombing machine.

Elizabeth Cartwright, the wife of the Rev. John Penrose. This lady, under the name of Mrs. Markham, wrote several elementary histories.

Edmund Cartwright's first wife was Alice Whittaker of Doncaster, by whom he had five children, of whom the most celebrated was his second daughter, Elizabeth, who was born in 1780, and married the Rev. John Penrose, for many years Vicar of Fledborough. Before her marriage she lived with her aunts at Markham, and it was as "Mrs. Markham," that she wrote her History of England and History of France, which for many years were the standard books of history for the young, to be found in nearly every schoolroom in England, and for which there is still a sale. There is a characteristic and amusing extract from a letter of hers to a sister-in-law of June 1823. Women authors are not so modest nowadays.

"Our reception at Heydon was most friendly, I like Mr Horseman very much, and Mrs. H. still more. She is very pretty and engaging, with an openness and simplicity that is very winning. It is a nice little tiny baby, and such a darling ! Mrs. H. is all anxiety about its health, and he already planning about its education, and consulting your brother about children's books. Mr H. 'There is a new History of England by a Scotch lady mentioned very highly in the Literary Journal, have you seen it ?' Mr J. P. 'What is the title' ? Mr H. 'I'll go and see.' (goes out and returns) ' It is by a Mrs Markham, do you know anything of it ?' Mr J. P. 'I have seen it, (after a short pause) it is a very pretty book.' Luckily nobody looked at me, for I am sure I looked all manner of things, however, if they did, I comforted myself with thinking they would only suppose I had scalded myself with hot tea !! ! "

The following letter by Mrs. Penrose is an account of a great Trent flood which took place in 1809, just a hundred years ago,

"If my dearest Aunt Pender could peep at poor little Fledborough Parsonage at this moment, would she laugh or would she cry ? Why I believe the latter would be the case. But were she to enter the isolated little dwelling, her eyes would soon be dry, if the sight of nine happy prisoners could do it. I will give you a short journal of the Flood. On Saturday night, the water was rising rapidly, but was not so high as we had many times seen it before. About two o'clock, William (our man, and the hero of my tale) who had risen to look after the cattle, alarmed our maidservants by informing them that the kitchen was covered with water. They arose and prepared the back parlour, waded to the coal-heap and brought in a stock of that necessary article, and having made some other arrangements, they were beginning to compose themselves to sleep by the back parlour fire, when the enemy rushed in, and drove them away from their temporary retreat. You may imagine there was not much sleep enjoyed in the family this eventful night, but I believe no member cared as much for anything as for the poor animals out of doors. But it would take up too much of my paper to give you a description of all our hopes and fears on their account, suffice it to say that the greatest part of them are at Mr. Bretts. Two horses and seventeen of our sheep are on the little bit of dry land, which is left of our Churchyard, and two fat oxen in a stable up to their knees in water. But the fate of the rabbits and fowls give us most uneasiness, three of the former are drowned, but the rest are safe in boxes on the stairs. The poor fowls ever since yesterday morning have been perched in a tree, and disappearing one by one, we suppose through weakness from want of food, and the very high wind. Mr R has come frequently under our window in his boat to enquire if he could do anything, and Mrs Crawley sent three men in a boat yesterday to offer provisions, and to say she could not sleep without knowing how we were. We had the satisfaction of returning for answer that we were very well provided for, and I believe still we should be able to stand a weeks siege. You can hardly conceive the rapidity of the current over the bank leading to the church, which is the only way our man can go out to fodder the cattle, and sometimes the horse he rides seems with great difficulty to stem the current."

Mrs. Penrose's elder sister, Mary, who was the wife of Mr. Henry E. Strickland, wrote her father's life with such force and sympathy, that the late Lord Masham said that to read it always brought tears to his eyes.

The youngest sister, Frances Dorothy, was adopted by her uncle, "the honest Major," and afterwards wrote his life besides keeping voluminous diaries.

Undeterred by his uncle's warnings, their only brother, Edmund not only became an antiquary, but also, on the disbanding of the Yorkshire Militia, in which he held a commission, took Holy Orders. His former Colonel, the Duke of Norfolk, in due time presented him with various livings in Sussex, and he afterwards became Canon of Chichester. He wrote part of the history of West Sussex.

From a dramatic point of view, it is certainly interesting that the union of the Ossington and Ordsall branches of the Cartwright family should have resulted in the production of three such intellectual giants, and that this old Nottinghamshire family, after 300 years of more or less humdrum, if vigorous existence, should have culminated in a blaze of genius, and in the person of Dr. Edmund Cartwright have left its name imperishably inscribed on the roll of fame.