They were always fitted with at least three apertures, one to look to the altar, one for light and ventilation, and one for the supply of food and other communications between the anchorite within and the world without. This eventually developed into a permanent structure, fitted up with a "jakes," or retiring closet, a fireplace, and a door,1 in addition to the windows, the vow being held sufficient to keep the anchorite from straying.

The will of Henry, third Lord Scrope of Masham, dated June 23rd, 1415, contains a long list of bequests to anchorets, including "the anchoret of Kneesall near Southwell xiij.s. iv.d." but no trace of this anker-hold remains. The nearest approach to a chamber of this kind in the county is at Hawton, where the north wall of the chancel is pierced with an oblique opening to give a view of the altar from the sacristy; also at Lambley, where a similar "squint" communicated with a "reclusorium," or "domus inclusi," a chamber built over the sacristy, but now destroyed.

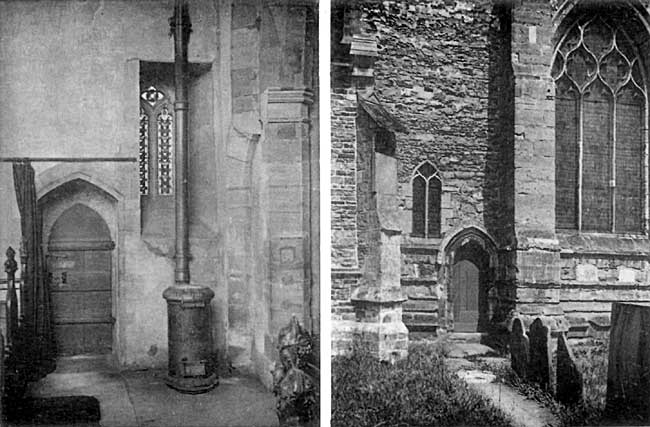

At Upton there is a chamber in the upper stage of the tower, fitted with a fireplace, and having a window (now blocked up) to look down into the church. At a later date this chamber was converted into a "columbarium." It is the only instance I know of a church tower being used as a dovecote. At Holme, near Newark, a small chamber over the south porch was made habitable, the last occupant being the renowned Nan Scot, who there survived a visitation of the plague, which decimated the village. Another fine example is over the north porch at Southwell, but Southwell being a collegiate church, is scarcely included in the scope of this paper.

The following is a classified list of all the shuttered openings to be found in the county :

Class A.

| Church | Style or Period | Position in Chancel | Present Condition | General Remarks |

| Barnby-in-the-Willows (All Saints) | Decorated | S.W. & N.W. | Glazed | Indication of Shutter |

| Basford (St. Leodegarius) | E. English | S.W. | Built up | Only seen outside |

| Burton Joyce (St. Helen) | Decorated | S.W. | " | " " |

| Collingham, S. (St. John Bap.) | " | S.W. | Glazed | Indication of Shutter |

| Costock (St. Giles) | S.W. | " | " " | |

| Flintham (St. Augustine ofCanterbury) | E. English | S.W.& N.W. | Built up | " " |

| Gedling (All Hallows) | " | S.W. | Partly built up | " " |

| Halam (St. Michael) | Decorated | N.W. | Built up | Only seen outside |

| Haughton Chapel | " | S.W. | In ruin | |

| Keyworth (St. Mary the Virgin or St. Mary Magdalene) | E. English | S.W. | Glazed | Indication of Shutter |

| Laxton (St. Michael) | Decorated | S.E. | " | Traces of Shutter |

| Littleborough (St. Nicholas) | E.E. insert, in Norman | S.W. | Built up | No trace left |

| Low Marnham (St. Wilfrid) | Decorated | S.W. | Glazed | Indication of Shutter |

| Normanton-on-Soar (St. James) | Decorated insertion | S.W. | " | " " |

| Nuthall (St. Patrick) | Decorated | S.W. | Built up | Only seen outside |

| Orston (St. Mary) | E.E. (restored) | S.W. | Glazed | Indication of Shutter |

| Stanford-on-Soar (St.John Bap.) | Decorated | S.W. | Built up | " " |

| Trowell (St. Helen) | E. English | N.W. | " | Probably shuttered |

Class B. Glazed Openings.

We have next to consider a series of openings of a different type, and, generally speaking, of a later period, made for the purpose of giving light, and occasioned by the introduction and development of the rood-screen. During the opening years of the 13th century the simplest form of the chancel screen made its appearance. It gradually developed until the 15th century, by which time it had become the most prominent feature in almost every church. So thoroughly was the rood-screen destroyed at the Reformation, that we are scarcely able to realize from the fragments that remain how imposing and extensive the structure must have been. Surmounting the screen were the images of the Crucified, Mary His mother, and St. John. A loft, about five feet wide, was necessary to give access to the lamp which was kept burning before the images, and to the row of lights which were placed along the top of the hand-rail at the great festivals, also for the purpose of veiling the images during Lent. The projection of the loft generally formed a canopy for the two altars, which stood on the west side of the screen, but there is evidence that in some cases the projection was eastwards, i.e. into the chancel, thus necessitating a special arrangement of the fenestration in order to get light either for general purposes, or to enable the priest to read his "Hours" at the desk, which otherwise would be dark thus placed beneath the soffit of the loft.

With this fact in mind let us examine the chancel at Car Colston, built circa 1360, by the York school of craftsmen.

Car Colston.

The north wall is divided into two equal bays by a bold projecting buttress, and each bay is pierced by a large three-light window. On the south side a more difficult problem presented itself. Those who are familiar with the work of this particular school will not need to be told that with them the sedilia received great consideration. This was built in the most fitting position in the south wall of the sanctuary, and flanked on either side by a window corresponding with, but not opposite to, the windows on the north side, thus leaving a narrow bay at the west end, which contains the priest's door, and a very small two-light window. If we look within, we shall find further indications that the rood-loft in this case projected eastwards, for the eastern face of the chancel arch is quite plain and the mouldings on the responds are not returned but cut off square and flush with the walling. A section of the original panelling of the screen pierced with three confessional or "peep" holes, is still in the church, fixed against the east wall of the south aisle, and as this exactly corresponds with the mortise holes in the masonry of the chancel arch and piers, its original position is thus clearly defined; but no trace of a staircase or doorway for entering the loft can be found.

A careful comparison between this work and the chancel at Arnold—built about thirty years earlier by the same school—where a stone newel staircase leading from the south aisle to the rood-loft is worked in the respond of the chancel arch, leads me to conclude that a similar arrangement was adopted here, but probably the stairs in this case led from the chancel and were made of wood instead of stone. It would therefore be necessary to get light at this point, and the skill of the builders is manifest in the introduction of this small but beautiful window, for a special purpose. The absence of a rear-arch and substitution of a flat soffit indicates that it came quite close up to the floor of the rood-loft; it has a sloping cill, to throw the light downwards; a quadrant splay to the westward to distribute the light and give access to the rood-stairs; and a square reveal to the eastward because the window was separated from the priest's door by a jamb only 8½in. wide.

The glorious church of St. Andrew at Heckington, built at the same period and by the same school, furnishes another illustration of a successful attempt to get sufficient light at this part of the church. The arrangement of the plan is unique, for the transepts spring, not in line with the chancel arch, as is usual, but one bay to the westward; the chancel walls are continued in line, and are pierced with two large windows, superimposed. A circular staircase in the responds of the chancel arch on either side indicates that the rood-loft once stretched across the space between the chancel arch and the transepts; the lower windows gave light on the altars beneath the loft, the upper ones were for the benefit of the minstrels and singers who, upon the loft, sang and played on festival days. Hence the worn appearance of the stone stairs leading up to the loft, caused chiefly by the hob-nailed boots of the villagers, and not by the feet of the priest. In cathedral, monastic, and collegiate churches, the Epistle, Grail, Alleluia, and Gospel were sung from the pulpitum loft; but we must confine our attention to parish churches.

Other good examples of windows to light a rood-loft may be seen on both sides of the clerestory at Claypole and Addlethorpe, in Lincolnshire, the latter being often quoted as a leper window, although it is many feet above the ground, and not easily accessible. In my opinion, windows of the Addlethorpe type were originally intended to light a "doom," painted on the tympanic screen beneath the chancel arch. (A very good specimen of a tympanic "doom" has been discovered in the guild chapel at Stratford-on-Avon.)

Wherever the rood-loft projected far into the chancel it was necessary to obtain light beneath it, and where the original fenestration did not admit of this, a small special window was introduced for the purpose. I think it will be found that in all cases where the jambs were not originally rebated for shutters, the "low side window" has been inserted after the introduction of the rood-loft for lighting purposes. When the Early English chancels were built, the lighting of a church—other than ceremonial lighting — received very little consideration. Narrow lancets, with cills high above the floor, were deemed sufficient, while the north wall was frequently built without any windows at all. When the Friars came they were supposed to know the service by heart, and MS. sermons were unknown. "Carry nothing with you for your journey! Not a Breviary! Not even the Psalms of David! Get them into your heart of hearts, and provide yourselves with a treasure in the heavens. Who ever heard of Christ reading books save when He opened the book in the Synagogue, and then closed it, and went forth to teach the world for ever." ("Coming of the Friars," Dr. Jessop.)

But as time went on, the desire for more light was felt, and was met by the insertion of these small special windows or by setting the lancets in pairs, and later in triplets; and not infrequently the small east window was taken out and fixed at the west end of the south wall of the chancel and a new and larger east window provided (Sutton St. Ann's). At Kneesall portions of the original lancets may still be seen in the south wall, blocked up with masonry. In their stead two beautiful three-light square-headed windows were introduced when the chancel was extended eastwards in the Perpendicular era; and the same thing occurred at East Leake, where a portion of the lancets still remain, although superseded by larger windows.

(1) It is interesting to notice that in the very complete example of a "priest's room" at Warmington, Warwickshire, the communication between the chamber and the chancel is by means of a small unglazed aperture, fitted with a wooden shutter like a " low side window."