Autumn Excursion.

VISIT TO SOUTHWELL.

A HALF-DAY excursion to Southwell was arranged by the Council for Thursday, September the 14th, when Mr. A. Hamilton Thompson, M.A., F.S.A., gave an account of the cathedral, the substance of which is contained in the following paper; an exceptionally large number of members and their friends attending the excursion.

THE CATHEDRAL CHURCH OF THE BLESSED VIRGIN MARY, SOUTHWELL.

By Mr. A. Hamilton Thompson.

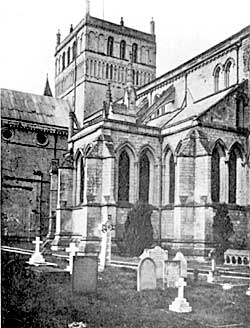

Southwell Minster — view from the north-west.

The early history of the collegiate church of Southwell, "the hed mother Churche of the Towne and Countie of Nottingham,"1 is extremely obscure. In an uncritical age, its foundation was ascribed to Edgar the Peaceable, who was also held responsible for the foundation of the colleges of All Saints at Derby, St. Mary's at Shrewsbury, St. Mary's at Stafford, St. Edith's at Tamworth, and other similar establishments in the Midlands. The stray notices of its existence in Saxon times, however, prove that the archbishops of York, at any rate during the half century before the Conquest, regarded Southwell and its church as possessions which demanded their special care, and that the staff which served the church was a body of secular canons, who derived their income from definitely assigned prebends. In 1051 Archbishop Alfric died at Southwell.2 His successor, Cynesige or Kinsi,3 gave bells to the church. Aldred, the last Saxon archbishop, founded prebends and built a frater or common dining-hall for the canons.4 These statements of a 12th century chronicler5 do not carry us back to the foundation of the church or the first appearance of secular canons at Southwell, but the last may point to Aldred as the real founder of the earliest prebends attached to the canons' stalls. The life of the collegiate body suffered no change at the Conquest. Domesday Book bears testimony to the existence of prebends in the church.6 The first two Norman archbishops seem to have done little or nothing towards increasing its revenues; but Archbishop Gerard died here in May, 1108,7 which is evidence that their manor-house at Southwell was one of their occasional residences.

Gerard's successor, Thomas II., may fairly be regarded as the founder of the existing fabric. In an important document, of which a copy exists in the White Book, which may be described as the chartulary of the collegiate church, Archbishop Thomas exhorts the people of Nottinghamshire to give alms to build the church of Southwell, and, in furtherance of this object, remits their obligation to attend the Whitsuntide procession at York, enjoining them to visit Southwell instead.8 This document is without a date, and the archbishop in whose name it was issued may have been Thomas of Bayeux, the first Norman Archbishop of York, and uncle of the second Thomas. But the York chronicler, who was a contemporary of Thomas II., says that it was he who obtained from Henry I. the same liberties for the canons of Southwell as were possessed by the canons of York, Beverley, and Ripon;9 and this grant may fairly be regarded as part of that step by which the church of Southwell was raised to the position of the archbishop's cathedral church in Nottinghamshire, and so took the place of York to the inhabitants of the southern archdeaconry of the great diocese.10

Of the church whose building Thomas II. thus furthered, some slight fragments of the eastern limb, with the fabric of the transepts, nave, north porch, and three towers still remain; and the architectural details show that little of the work can have been completed at the death of Thomas in 1114. Here, as in other great churches, the work of rebuilding would be begun at the east end, to provide the high altar, and to allow the canons to enter their new quire as soon as possible. The existing Saxon church would be demolished slowly, and the new work would proceed westward by degrees, as funds allowed. It is well known that in our larger churches of the 11th and 12th centuries, as at Durham or Peterborough, the work began with the construction of the eastern apse and the presbytery with its aisles. Piers were then raised to a certain height, with the intention of eventually building a central tower on them, and were provided with sufficient abutments on the sides of the transepts and nave. So much of the nave was built as would be sufficient to contain the quire of monks, or of regular or secular canons, as the case might be; for, in churches of this date, with their short eastern arms, the quire, as may be seen at the Benedictine cathedral church of Norwich and the secular cathedral of Chichester, occupied the crossing of the transepts and frequently extended into the eastern portion of the nave. The eastern bay of the nave with its triforium stage, and a bay of the ground-floor arcade to the west would be completed first, as at Durham and Selby; while the aisle walls would be set out, and, as at Selby, might be partially finished before the builders proceeded with the work of the nave. In almost every case, the building of the nave was a very leisurely affair: occasionally, as at Peterborough, the design was changed as the work went on, while the nave at Selby, begun before 1100, was not finished until more than a century later.

South Minster — Nave.

South side of Choir—Southwell.

East end—Southwell.

At Southwell great uniformity of design was preserved throughout the presbytery, transepts, and the lower portion, at any rate, of the nave. The two western responds of the presbytery arcade may still be seen at the back of the eastern piers of the central tower,11 and are practically identical in design with the responds and columns of the nave. This may be taken as proof that the eastern arches of the nave, at all events, were completed as part of the work which included the presbytery and was the earliest portion of the Norman rebuilding. Turning to the exterior, we find that one of the most striking features of the building is the string-course of chevron work which, broken only by the west and north doorways, ran round the whole of the nave and transepts at the level of the sills of the aisle windows. This is continued round the buttresses and along the interior as well as the exterior of the side walls of the north porch: it is raised in the segment of a circle to form a hood to the doorway of the south transept; and, although it was disturbed by the insertion of traceried windows in the aisles during the 15th century, the pieces removed were re-set below the new sills, and joined to the old string-course by bands of chevron taken from the jambs of the older window openings.12 The stringcourse below the small outer openings of the triforium is broken only by the inserted west window and by the eaves of the north porch, while the string-course below the clerestory was originally quite continuous, and is now interrupted only by the west window, which fills the space formerly occupied by two rows of round-headed openings.13 It can hardly be doubted that the outer walls of transepts, clerestory, and aisles of the nave, were completed upon one design within a comparatively short period. It is also highly probable that they followed the plan which may have been adopted between 1109 and 1114; but their architectural character is certainly of a date some years later than the death of Thomas II.14 The eastern arm of the Norman church was probably begun before or soon after 1114, and the tower piers with the eastern part of the main arcade of the nave were the next work completed. The rest of the nave arcade, the whole of the triforium and clerestory, the transepts, the aisles with their vaulting, and the lower stages of the three towers to a height just above the roof-line, followed. The final additions, the completion of the towers and north porch, the elaborate transept gables, and the magnificent north and west doorways, can hardly be earlier than the third quarter of the 12th century. In fact, much of the Norman work which remains to-day can hardly have been executed earlier than 1130-40, while the upper stages of the towers may not have been finished till after 1170. The conclusion of the work would thus fall within the pontificate of archbishop Roger of Pont-l'Eveque (1154-89), the prelate in whose time a new quire at York, and much of the existing minster of Ripon were built. The plan of the church thus completed was, as has been said, that which had been adopted from the first. The eastern arm was short. Its central division was an oblong, nearly corresponding in length to three bays of the nave, so that its east wall crossed the space between or just east of the middle columns of the present quire, a bay east of the modern stalls.15 Its aisles, a bay shorter in length, ended in semi-circular apses, which, with the eastern part of the aisles, were divided from the presbytery by solid walls : one arch on either side formed the communication between the presbytery and the western part of the aisles. The plan, allowing for differences in proportion, was that of the ordinary Norman monastic and collegiate church, with the important difference that a rectangular chancel took the place of the usual apse in which the high altar was placed. In this plan, as in the Norman example of Saint-Georges-de-Boscherville, and in England at Durham and Lincoln,16 we sometimes find an apse flanked by aisles, the east ends of which are rectangular outside, but internally semi-circular. At Cerisy-la-Foret and Lessay, the aisles are at present rectangular inside as well as outside, but the apse is semicircular.17 The arrangement at Southwell, the evidence for which rests on the statement of the late Mr. Ewan Christian, appears to have been peculiar to a few English churches; and, although the evidence as regards two or three of these is not exactly conclusive,18 the arguments of the late Professor Willis point to the adoption of this plan at Ely between 1103 and 1106.19

The transepts at Southwell were planned without eastern or western aisles. The division of their ends into two equal halves, divided externally by a pilaster buttress, so that the southern doorway is to one side of the centre, shows that the builders intended, as at Ely, Winchester, Lincoln, and several of the larger Romanesque churches of England and Normandy, to return the triforium passage along an internal gallery. This is also manifest in the interior of the church, where the windows of the lowest stage in the end walls are covered by two arches which project 2ft. internally, and spring from a cylindrical shaft in the centre of the wall.20 The transepts of Southwell had also, like those at Tewkesbury, Saint-Georges-de-Boscherville, and other Romanesque churches, apsidal chapels projecting from their eastern walls. The arch between the south transept and its eastern chapel is still in place ; and the line of the high-pitched roof of the chapel may still be seen upon the outside wall. The chapel in the north transept was taken down in the 13th century, when the present eastern aisle took its place. These chapels were not, as at Gloucester, connected by arches with the aisles of the presbytery, but stood quite free of the presbytery walls at a distance of some feet.

(1) Chantry Certificates, roll 13, No. 40.

(2) Chronicon Pontificum in Historians of the Church of York (Rolls Ser.), ii., 343.

(3) Ibid, 344.

(4) Ibid, 353.

(5) The whole tripartite chronicle is usually referred to as by the Dominican Thomas Stubbs, author of the middle portion (1140-1373). The earliest portion, down to 1140, is attributed to Hugh, precentor of York.

(6) Mr. A. F. Leach, F.S.A., Visitations and Memorials of Southwell Minster (Camden Soc.). pp. xxv., xxvi., notes that out of the estates of the canons mentioned in Domesday, at Southwell, Cropwell Bishop, Norwell, and Woodborough, were formed seven prebends (viz. Normanton, two of Cropwell, three of Norwell, and Woodborough). This may point to the original number of canons, as at Beverley and probably York and Ripon, being seven.

(7) Hist. Ch. York, ii., 366.

(8) Liber Albus, fol. 124.

(9) Hist. Ch. York, ii., 372.

(10) In Liber Albas, if. 18-20, is a copy of a letter from the chapter of York to the chapter of Southwell, containing the verdict of an inquest, taken in 1106, upon the liberties and customs of the church of York. This is printed in Visitations and Memorials (ut sap.), pp. 190-6. A charter of Henry I. in the Registrum Magnum Album of the dean and chapter of York (ii., f. 62d). printed in Hist. Ch. York, iii., 34-6, confirmed the privileges of York detailed in the above letter.

(11) The north-west respond is visible from the north aisle of the quire. The south-west respond is enclosed in and partly built up by the stair from the south aisle to the organ-loft.

(12) For adaptation of chevron work from old window-jambs and string-courses, cf. the chancel at Earls Barton, Northants., lengthened and largely rebuilt in the 13th century, and the chancel at Bloxham, Oxfordshire, also rebuilt in the 13th century.

(13) This was most probably the original design of the west front, which may be mentally reconstructed by a comparison with the west front of the abbey church of Saint-Georges-de-Boscherville (Seine-Inferieure).

(14) As the outer walls of the eastern arm of the 12th century church no longer remain above ground, it is impossible to say whether the string-courses of the nave were continued from them, or whether those of the presbytery and its aisles were of a less advanced design. The latter is probably the case.

(15) i.e. between the third and fourth bays of the present quire arcades, reckoning from the east.

(16) For the plans of the 11th century eastern arms of Durham and Lincoln, see articles by J. Bilson, F.S.A., in Archceol. Journal, liii., 1-18, and Archaeologia, lxii., 543-64. Other English examples were the abbey churches of St. Albans and Peterborough. Mr. Bilson, Archaeologia, u.s., p. 555, also quotes the church of St. Nicolas, Caen (Calvados), and the abbey church of Montivilliers (Seine-Inferieure).

(17) Plans in Archaeol. Journal, U.S., p. 17. Mr. Bilson notes, Archceologia, u.s., p. 555, that the ends of the aisles at Cerisy and Lessay "have been altered from their original form, which was apsidal internally."

(18) See F. Bond, Medieval Church Planning in England (Builder, vol. xciii., pp. 132, 133).

(19) D. J. Stewart, Architectural History of Ely Cathedral, 1868, pp. 24-30.

(20) The gallery in the north transept was probably removed in the 13th century, when the present eastern aisle was constructed.