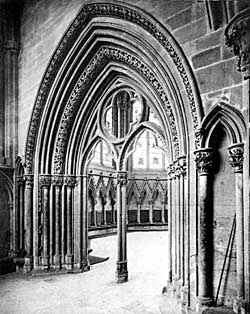

Chapter House—Southwell.

The date of the erection of the chapter-house is settled by a document in the register of archbishop John le Romeyn, who brought the number of prebendaries to the final quota of sixteen by the foundation of Eaton prebend in 1290, and the carving of North Leverton prebend out of Beckingham in 1291.1 In 1293 he ordered penalties incurred by nonresident canons who allowed their houses to become dilapidated to be applied to the fabric of the new chapter-house,2 and it is probable that by this time the walls had risen to a certain height. The work of the chapter-house is thus contemporary with the design of the nave of York minster, the foundation stone of which was laid by Romeyn in 1291,3 and with, at any rate, the beginning of the great chapter-house at York.4 We hear of no older chapter-house at Southwell, but the blocked doorway in the north aisle of the quire seems to indicate that there was one, and the existence of the old chapter-house probably accounts for the way in which the passage to the new chapter-house was built so close to the east wall of the chapel of the north transept. It is clear that this passage, the west wall of which is built up in sections between the buttresses of the transept chapel, and flush with their outer faces, was begun some time before the new chapter-house was taken in hand. There is a wall-arcade on either side. The arches on the east side, with filleted rolls and deep hollows, and projecting hoods resting on corbels sculptured with heads and foliage of unmistakably 13th century character, spring from lintels, the outer faces of which form the capitals of a front and back row of detached shafts. These have tall bases without water-hollows resting upon a bench table. The full effect of this arcade is injured by the walling-up of the openings as high as the soffit of the lintels ; above this point the heads of the openings are glazed.5 The western arcade was necessarily intended to be a mere wall-arcade without piercing, and the arches are trefoiled with soffit-cusping. It is also somewhat later than the eastern: its mouldings agree with those in the vestibule of the chapterhouse. The walls of the passage appear to have been completed as high as the scroll string-courses above the arcades. The capitals were for the most part left to wait for their sculpture, and no door was pierced through the quire wall till later. The work was probably begun between 1260 and 1270, and then abandoned for a time, but soon after 1290, the abandoned work was taken up again; the octagonal chapterhouse was built, and a vaulted vestibule made at the end of the passage. As the new vestibule was considerably higher than the existing walls of the passage, an upper stage of very plain design was added to them at a rather later date and pierced on the east side by a row of windows, and the passage was covered with a wooden roof.6 When the chapter-house was ready for use a wide doorway was pierced through the wall of the north aisle of the quire, above which a new three-light window, with pierced spandrils in the head, took the place of the previous pair of lancets.7 The unfinished capitals and lintels of the passage were carved with naturalistic foliage, which harmonises with that of the chapter-house, but is less deeply undercut. The very beautiful sculptured foliage of the chapter-house was probably executed by degrees after the fabric was finished.

Corridor to Chapter House—Southwell.

The doorway of the passage from the quire consists of a round-headed arch, divided by a central shaft of Purbeck marble into two acutely pointed openings. The spandril is pierced with a trefoil. Purbeck marble is also used in the outer shafts of the jambs. The two doors open inwards to the passage, and at the back of the central shaft is a coiled figure of a serpent, in which are holes for the door-bolts. Marble is also employed in the doorway of the chapter-house, but nowhere else in the church. The stone which was employed for the chapter-house is a fine local sandstone of a light yellow colour. The passage has already been described. The junction between the passage and the vestibule of the chapter-house on the west side is formed by the eastern angle buttress of the chapel of the north transept; but on the east side the early arcade ends at a point further to the south, and is succeeded by a wall-arcade similar to that in the vestibule, in which is a round-headed doorway to a stair which leads to a room above the new vaulted bay. The vestibule itself projects entirely beyond the north wall of the transept chapel, and forms an oblong roofed with a quadripartite vault. It is lighted by two windows of three lights with cusped circles in the head, one in the north, the other in the west wall. Below these windows the walls are arcaded. Both here and in the chapter-house, the arch mouldings are treated so as to harmonise very fairly with the earlier mouldings of the passage, and there is a deep hollow between the filleted rolls of the inner and the plain rolls of the outer mouldings. The sculptors throughout the building manifested a passion for undercutting mouldings and ornament which was becoming unusual elsewhere at this period, and was certainly never surpassed, even in the most exquisite work of half a century earlier.

Chapter House doorway—Southwell.

The doorway of the chapter-house, on the east side of the vestibule, is divided by a central pier into two trefoiled openings. The spandril between these and the outer arch is pierced by a quatrefoiled circle. The great arch is deeply recessed and moulded in three orders, with corresponding shafts in the jambs. Beneath the hood is a wide band of carved foliage, very deeply and thoroughly undercut, with minute attention to naturalistic detail. A keeled bowtell in the middle order of the arch is covered by a similar band. The inner and outer orders are moulded with filleted rolls, divided by deep hollows. The capitals of the jamb-shafts are most richly sculptured with naturalistic foliage, and a slender band of foliage covers the hollow in the outer jamb of either side of the archway, on the west side of the outer shaft. While the foliage of the quire consists of bold conventional leaf-work united to the capitals by stiff "stalks" of the usual 13th century type, that of the chapter-house consists of sprays, each leaf of which has its own delicately carved stem joining it to a slender stalk which lies within the hollow moulding or on the capital, and is carved so that it appears to be applied to, instead of springing from, the stonework.8

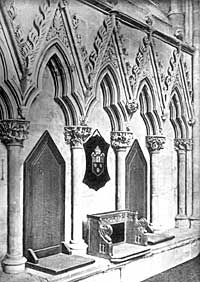

Canopied stalls in Chapter House—Southwell.

The remaining seven sides of the chapter-house are surrounded by a stone bench-table. Above this in each bay are five acutely trefoiled arches divided by shafts. The arches have straight-sided pediments with crockets of great size and beauty; the finials pierce the filleted string-course which divides the wall arcade from the windows. The spandril between each pediment and its arch is filled with sculptured spray and leaf work of a variety and invention as marvellous as that of the capitals. In six out of the eight bays is a three-light window with cusped geometrical tracery: fragments of the old glass are left, but it needs some imagination, which may be helped by a memory of the glass at York, to realise the magnificent colour which once must have filled this beautiful building, the deep tones of the glass relieved and brightened by the gayer colouring and gilding of the sculpture. The west bay, next the vestibule, and the southwest bay, in the outer wall of which is the stair to the roof, are not pierced for windows, but have blank tracery of the same character as the rest. The chapter-house, like that at York, is without a central column, and is vaulted in eight compartments, the transverse ribs of which spring from angle shafts between each bay and meet at a central boss. The shafts are not corbelled out, but rest on the stone bench below the wall-arcades. In each compartment of the vault are two leaning arches formed by tierceron ribs and connected by a ridge-rib with the central boss. The outer pressure of the vault is taken by great angle buttresses; there are similar buttresses at the north-west angle of the vestibule. The present pyramidal outer roof is a reproduction of the probable pitch of the original roof.9

Capital—Chapter House—Southwell

Capital—Chapter House—Southwell

A natural comparison arises between this building and the far vaster chapter-house of the mother church of York. Great though the variety of detail is at York, there can be no question that Southwell, with its completed stone vault and its intricacy of sculptured ornament, is the lovelier and more perfect structure. In two respects it is inferior to York; it has less majesty of proportion, and it no longer has its full complement of stained glass.10 But, apart from this, there are few who would deny, even when the beauty of the chapterhouses of Westminster, Wells, and Salisbury is taken into account, that it is unsurpassed by any similar building in England. Built at the epoch at which medieval architecture had reached its zenith, it realises the ideal of Gothic construction, the vaulted and buttressed building whose walls admit a maximum of light. Its traceried windows, without superfluous stonework, keep the pure outline of those simple curves and restrained decorative forms which mark the most dignified, and to some of us the most beautiful, period of medieval art. In the mouldings individual expression is given to every single member, and a bold contrast of light and shade is obtained by means which, for a century past, had given English buildings their chief charm. In the sculpture which has made this chapter-house famous, a less conservative spirit is apparent. If no detail is left unfinished, if every individual piece of the work can bear the closest inspection, there is yet an absence of the vigour which is so remarkable in the sculptured corbels and capitals of the upper portion of the quire. There the stonework seems to spring into spontaneous life, and the conventional sculpture bears the closest relation to the structure of the building. Here the sculpture, in which nature is so carefully and delicately studied, gives the impression of applied decoration, in which the detail fills the carver's mind, for the time being, and the structure to which it should add emphasis is somewhat forgotten. Such perfection could not be maintained, and the pulpitum and sedilia, within the next half century, show the inevitable decline to mere ornament for the sake of ornament ; and, beautiful as they are, their sculpture is yet crowded, florid, and more satisfactory at a distance than near at hand. But, taking the whole work of the chapter-house by itself, and forgetting the danger of the precedent which the carvers set to their successors, we may well apply to it the proud words which were written of its greater sister at York—"Ut rosa flos florum, sic est domus ista domorum," "As the rose is flower of flowers, so is this the house of houses."

Of this house, then, the chapter took possession between 1290 and 1300. Master Henry of Newark, dean, and afterwards archbishop of York, Master Reynold St. Alban, the clerk and confidential friend of more than one archbishop, Master John Clarell, the holder of many benefices in Nottinghamshire and Yorkshire, and one of the most able agents of the see of York, Sir Richard Bamfield, the archbishop's seneschal, Master Bonet St. Quintin, a trusted envoy of Edward I. to France and Flanders, and Master Benet of Halam, a faithful servant of the church of Southwell, were among the canons who watched its building or were the earliest to gather within its walls. This may be an ideal picture, for the canons of Southwell, as of other secular churches, were more regular in absence than in residence.11 However this may be, the chapter-house gave the great collegiate church its find structural perfection. As time went on the church, as we have seen, gained in beauty of furniture. Also, as years passed, it inevitably submitted to certain changes, which altered the external appearance of the building in some degree, and were apparent internally in the nave. In this respect, however, it underwent less change than most of our great churches. The cathedral church of the diocese of Southwell affords us one of the most instructive epitomes of the history of medieval architecture which we possess, because its various periods of building are so clearly defined, and because in each part of it we may study one particular phase of the art, unperplexed by the presence of those mingled details of various dates which often make the history of a building so difficult, if so fascinating, to reconstruct. In the nave, transepts, and towers, we may study the progress of 12th century Romanesque from the time when it reached its height to the very verge of the transition to Gothic work. In the quire we have a logically and harmoniously designed masterpiece of 13th century Gothic at its zenith. And in the chapter-house we can see the ultimate structural perfection at which the builders of the 13th century aimed, enriched with a wealth of ornament which no other sculptors of the period can be said to have excelled or even rivalled.

(1) See notes on certificates of the college and chantries in the following article.

(2) A. F. Leach in Vis. and Mem., p. xvi. This and a large number of documents relating to Southwell and to Nottinghamshire generally will appear in Mr. W. Brown's edition of archbishop Romeyn's register, now in the press, for the Surtees Society.

(3) Hist. Ch. York, ii., 409 (6 April, 1291).

(4) The date of the York chapter-house is much disputed; but the shields-of-arms in the windows indicate the last decade of the 13th century as the period to which it should be assigned, and there is nothing which makes this date in the least improbable. The passage at York by which the chapter-house was joined to the north transept was not begun until the chapter-house itself was completed.

(5) The original design is better appreciated, if seen from the small yard beneath the north aisle of the quire and the chapter-house, which probably covers part of the site of the older chapter-house, if there was one.

(6) This upper stage of the passage seems not to have been added until the chapter-house had been fully completed. The carved figure in which the string-course, which divides it from the earlier work, ends, is of a type of carving as late as 1320-30.

(7) This window clears the roof of the passage, which possibly had a temporary high-pitched roof until the upper stage was added.

(8) One or two experiments, in which the older type of conventional sculpture is reverted to, are to be noticed among the capitals in the interior of the chapter-house. Various figure subjects are introduced among the foliage of these capitals, not merely on the outer surface, but in the interstices of the undercutting.

(9) The view in Dickinson, op. cit., shows a roof of somewhat lower pitch than at present.

(10) At York one of the windows is filled with modern stained glass.

(11) Something about the residence of the canons will be said with relation to the certificates of the college and chantries. It is sufficient to say here that the number of residentiaries in any medieval chapter was usually extremely small, and that the place of non-residents was served by the vicars attached to their stalls, who formed an integral part of the foundation.