Carburton church

By Harry Gill

The village of Carburton in the 1980s. Manor Farmhouse, a late 17th century stone house, is on the far right; the tiny church of St Giles sits in the middle. (A. Nicholson, 1986).

The "Chappell of Carberton" is one of the three chapels-of-ease to "the antient mother church of Edwinstowe." It stands, as Domesday form of the name implies, on "the Cars," or land liable to flood, in the "barley enclosure" of the king’s manor of Mansfield (Carbertone).

The edifice is small and severely plain, but nevertheless, its "quaintness" and general air of antiquity excites our interest.

The plan is a simple parallelogram, 50ft. long by barely 15ft. wide (14ft. 10in.), comprizing chancel and nave under one roof, with a porch at the south-west and a small vestry at the north-east.

The walls, covered externally with "rough cast" stucco, and smoothly plastered within, are nearly 3ft. in thickness (2ft. 9in.), and still retain three of the original windows–two at the east end and one on the south side. These small, round-topped loop windows, under 3ft. in height (2ft. 9in.), and only 6in. wide, placed fairly high up in the wall, deeply splayed within, and having the glass line almost flush with the outside face of the wall, are very characteristic of a small village church of early Norman times, and suggest the opening years of the 12th century as the most probable date of erection.

Originally the east end had three of these small windows, arranged probably in the same way as at Sookholme, but after the lapse of a century or so (i.e. circa 1200) a lancet window of more ample dimensions was substituted in place of the central loop.

The remaining windows–two on the south side, one on the north side, and one at the west end–were supplanted, probably during the reign of Edward I., by two-light windows of the Decorated type. It is almost impossible to date this style of window accurately, because, being simple in design and easy to execute, they were used in village churches without much variation all through the reigns of Edward I. and II. Further confusion arose when, in the 17th century, the pattern became a favourite one for church restorations, and earned the epithet of "churchwardens gothic."

St Giles' church, Carburton, in 2003 (© A P Nicholson, 2003).

We shall meet with exactly the same kind of window at Edwinstowe, and I should fix the date of the examples here and at Edwinstowe in the last quarter of the 13th century.

The modern porch covers a round-arched doorway of early Norman type, 3ft. 4in. wide, having plain chamfers to jambs and arch, and grotesque masks to stop the hood moulding. Notice also the incipient chevron ornament on the reveal of the lowermost stone in the western jamb.

A double sun-dial, inserted in the south-western angle of the main wall above the porch, produces a peculiar effect, owing to the building being not truly oriented; the right-angle faces of the dial are consequently not in line with the wall face on either side.

One might be pardoned for describing the excrescence on the western gable as a dovecote, but in reality it is a square bell-chamber, containing one bell.

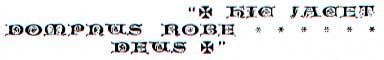

On entering the church, it will be seen that the stone paving within the doorway comprizes fragments of incised memorial slabs of 14th century type. One stone contains the foliated cross head of a grave cover, separated from its shaft and calvary, which have been broken or cut away, and laid at right angles to it. Another stone is a portion of a memorial to a dignitary of the church, whereon may yet be traced the upper half of a priestly figure, clad in amice, grasping with his right hand a pastoral staff, the head of which has now become quite illegible. This, I think, can be no other than Robert de Spalding, a Canon of the Abbey of Welbeck, who was elected Abbot in 1341, and died of the plague in 1349. The lines of a beautiful ogee canopy, and a portion of the marginal inscription, in Lombardic capitals, are still clearly visible:--

Carburton Storth, a much disputed possession of Welbeck Abbey, lay between the abbey gateway and Carburton Church.

The plain, bucket-shaped font, mounted on a circular base, has been described as "Saxon" work, but I can find no justification for the statement. The bowl is lead lined, and has an outlet at the base: the internal dimensions are 23in. diameter, l0in, deep. The size and shape of the font, and the general character of the work is almost identical with other early Norman fonts in the district, and I have no hesitation in fixing the date, circa 1100, i.e. contemporary with the doorway, the "loop’s windows, and the stuccoed walls.

There appears to be no reliable data concerning the history of this church, other than is to be found on the ancient stones. Even the early dedication is unknown. The York Records have been searched in vain for any reference to it, and Canon Raine has entered "not found" against it in his list of Nottinghamshire dedications. Like the last church we visited, and the next on the list to be visited, it is now known as "St. Mary’s," a very usual dedication for forest churches.

A square recess in the south wall marks the position of the piscina, while a similar recess in the north wall above the communion rail appears to have been used as an aumbry, but alas I the ancient altar vessels which once were kept therein are not to be found. I think I am right in saying there is not a single specimen of a pre-Reformation chalice or paten left in the county. The vessels still in use here, however, are not without interest.

The Elizabethan communion cup and paten cover is one of a large number of similar cups, supplied by order of the bishops between 1568-1578. It is made of silver, 5in. high, 3in. across the brim; the bowl is enriched with an engraved band of Renaissance ornament; there is no knot in the centre of the stem, which is the only point of difference between this and hundreds of other cups of the same date. The paten or cover is also quite plain, save that the date–1571–is engraved on the foot.’

The registers here (and at the sister church of Perlethorpe) are among the earliest in the country. The entries commence with the year 1528, i.e. ten years before the keeping of registers was made compulsory.

On the 5th September, 1538, an Injunction was issued by Thomas, Lord Cromwell, to every parish in England and Wales, ordering the "parson, vicar or curate" to "kepe one boke or registere, wherein ye shall write the day & yeare of every wedding, christening & burying made within your parishe."

The Carburton parson of that time must have been a loyal and painstaking son of the church, for he promptly obtained a register and copied into it all that he knew of former happenings, prefacing the entries with this sentence— "The register book of Carburton, as have been Christened maried and bured in the parish of Carburton since the beginning of the yeare of our lord god and the five hundred twentie and Eight."

In 1729, a later incumbent introduced into his register book a system of hieroglyphics, placing a cross before christenings, a death’s head before burials, and a pair of claspers before weddings, but we saw, on a former excursion, that Rector Wm. Sampson, of Clayworth, had forestalled him in this, having adopted the system in 1676, save that he employed a ring for weddings, in place of the claspers.

These interesting registers will be on view at Edwinstowe, whither they have been taken for safe keeping.