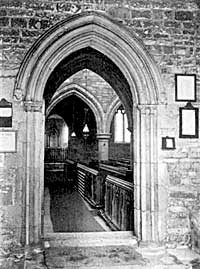

![Edwinstowe church. Nave arcade [north].](../../../../images/edwinstowe/tts1914/arcade-detail.jpg)

Edwinstowe church. Nave arcade [north].

The plain, round piers of the north arcade, the right-angle head mouldings to the capitals, which are separate from the bell and necking, the water-holding base mouldings, the pointed pier arches having two orders of simple chamfers which called for little labour and skill in execution, are all indications of the Transitional or semi-Norman style of architecture in vogue at the end of the 12th century.

The ornaments on the south front of the springing stones to the pier arches should not be passed without notice. Beginning at the east end there is a “tooth ornament,”—a development of the Norman " nail-head,"—on one side, and a characteristic “stiff-leaf” on the other. This treatment is repeated at the west end, save that the " tooth " ornament is employed on both sides; the outer order of chamfers of the two intermediate arches have terminals of an unusual kind-the design would be more appropriate at the head of a chamfer than at the foot of it. This is a small point, but it helps us in fixing a date. On the north front the chamfers are continued to the abacus, save in one case— i.e. the westernmost—where the ordinary mason-stop is employed.

The corbel heads at the hood moulding intersections, if original—as they appear to be—are interesting examples of sculpture of an early date. Taking into consideration time and circumstance, it may be more than idle fancy to suggest that the head on the eastern side of the second arch, crowned with a low Norman mitre, represents Geoffrey Plantagenet, (the youngest and the only faithful son of King Henry II. and the Fair Rosamund), who was Bishop of Lincoln, 1173, and Archbishop of York, 1191; while the powerful features and rich mitre of the ecclesiastic on the western side were intended to commemorate the new saint-Thomas a Becket ; murdered 1170, canonized 1173.

Edwinstowe church. Corbel: tower arch.

The corbels supporting the tower arch are good examples of their kind, and aptly illustrate: “the sinister grotesqueness of the carved head upon a corbel that leers and grimaces as light and shade go changefully over it” (Warwick Deeping). The head of the corbel on the south side is enriched with a band of “nail-head” ornament, while the one on the north side is plain.

Thus far we have been dealing with a period, styled in legal phraseology, “time immemorial,” but when we turn to examine the detail of the south arcade, we can call to our aid documents which tell us when and why it was built.

Two brothers, “Henry & Robert de Edenestou,” endowed a double chantry1 in this church. A full translation of the charter, which was signed, on the first day of the month of November in the Year of our Lord 1342, will be found in volume VIII. of the Society's Transactions.

The south aisle was built of unusual width (nearly 20ft.) for the better accommodation of the two chantry priests who were to perform their office at the “Altar of St Margaret within this Church.”

Edwinstowe church. South porch.

The south wall of the nave was removed, and gave place to an open arcade of five bays, and it is interesting to contrast this with the older work on the north side. There is some agreement in the general lines, but the contours of the mouldings are entirely different; this adds confirmation to the theory now generally held, that in each period, authorized mouldings were sent out from the chief school or lodge of the mason-guild, known at that time as the Guild of St. Mary at Lincoln, and all members of the craft were required to work to official templates. This is the reason why the work of any given period is found to be identical in detail with other work of the same period, no matter in what part of the country it may be found.

Notice the number of small members contained in the capital and base mouldings of the eight-sided piers; the pier arches, too, are elaborated by the addition of a “casement,” or deep hollow, in the centre of each chamfer: the hood moulding contains additional members as compared with the opposite side, and is repeated on both sides of the arcade, to add dignity and importance to the chantry chapel; the sculptured heads are worthy of notice, especially the one opposite to the south entrance, which has a wheel broach at the throat.

The south entrance doorway is an elegant specimen of the Decorated period (circa 1350), having filleted arch moulding and shafted jambs; but the two-light windows, with plain intersecting tracery,2 are of an earlier type (circa 1280), and may have supplanted lancets in the original south wall, from whence they have been taken and re-set. New drip moulds, having returned ends, were added in some instances, but the westernmost window on the north side, which belongs to the same series, is complete with a drip mould having mask terminations.

If this surmise as to date is correct, the recent find of a small coin beneath the surface of the ground at the west end of the church is of more than ordinary interest. It has been pronounced by Mr. W. J. Andrews, F.S.A., to be a silver penny of the reign of Edward I., the date of issue lying between May 17th and December 31st, 1279. The obverse legend is a contracted form of “Edwardus Rex Angliae, Dominus Hyberniae;” the reverse shews that it was struck at the Mint at London, “Civitas Londonie.” It is not improbable, therefore, that a mason, while employed upon these windows, had the misfortune to lose a portion of his wages, as the coin was found among broken stones and rammel which had been used for levelling up a cart track near the church.

At the eastern end of the aisle there are two aumbries, or cupboards (minus the doors), wherein the reserved sacrament, the holy oil and chrism, were wont to be kept.It is interesting to notice that here, as in so many other churches, the 14th century builders had no scruples about using up older work in their altar accessories, for in each case the cill of the aumbry is a portion of an incised grave cover, taken from the floor of the 12th century church.

The head of the cross calvary, enclosed within four open curves placed back to back, and the arcuated borders consisting of round arches on the sinister side and pointed arches on the dexter side, are marks of an early date.

A pair of wool shears on the dexter side of the cross shaft may possibly have been intended to denote that it was the grave of a lady, but in the absence of other symbols, the shears are generally held to be indicative of a civilian of position-a woolstapler, clothier, or merchant.3

A portion of a “mensa,” or altar slab (6ft. 5½in. long, 2ft. 8in. wide, 5½in. thick), whereon two of the five consecration crosses are still visible, has recently (1911) been re-fixed at the south-east corner of the aisle, near to the original position. The back edge of the stone was left rough for building into the wall, but the front edge is moulded in such a way as to leave little doubt that it is the original 14th century altar of St. Margaret, and the vicar is to be commended for having rescued it from a degrading position in the floor of the belfry.

There is a recessed piscina in the south wall above the altar, having a shelf or credence table for the altar vessels above the bowl.

The image brackets, one on either side of the window behind the altar, still remain. The images they once carried, being “objects of superstition,” were “broken & defaced” during the “great pillage,” but the altar vessel—i.e. “one Chalice sylver white Waying xj onz iij quart,”—being convertible, was “delivered vnto thandis of the Master of his gracis jewell house.”

“Henry of Edenstau, Clark,” one of the founders of this chantry, appears to have been a man well known in the district, having been Parson of the church at Warsop (resigned in 1332), and Prebendary in the cathedrals of Lincoln, Southwell, and Landaff. When he died, his body would surely be laid to rest within this church which he had endowed (1342), and of which his son, “Dns Tho fil Henri de Edenstowe was vicar 1335-1346.” (Torre MS.)

It is not unreasonable to assume that the incised stone1 (now in the north aisle) was originally laid down to cover his grave. The symbol it bears—a cross with fleurs-de-lys on the arms, the shaft rising from a tri-foliated arch in the base, with a chalice on the dexter side thereof—is such as would be used in the 14th century for a patron who was also a priest.

The stone is not now in its proper place. It was removed from the cill of the window at the south-east end of the aisle, but most probably the original position was in the floor, near the side altar.

(1) The two chantries were consolidated into one chantry by the Archbishop of York in 1399.

(2) This type of window, owing to its simplicity and facility for easy working, was often used in the 19th century restorations in the “Churchwarden” style. The “mask” terminals were used as early as 1230, and continued until the middle of the 14th century. Intersecting tracery continued as late as 1320.

(3) There is a similar stone with wool shears at Cuckney.