A local patron of architecture in the reign of Henry VI.

By Mr. Harry Gill.

"An Englishman's house is his castle." This has long been an axiom; but any time before the end of the Wars of the Roses, the primary need of an Englishman of position was a safe retreat. Yet, strange to say, even before that period of strife had well begun, a change in the style of castle building was apparent. By the end of the 15th century the change had become general. A measure of stateliness and comfort, combined with a fortified exterior was then in vogue, and an Englishman's castle became his house.

The progress of the change is marked by the fact that 281 "licenses to crenellate"1 (i.e., to top the walls with battlements consisting of merlons and embrasures or crenelles as a means of defence) were granted by the Crown during the fifty years' reign of Edward III., while only fourteen were applied for during an equal period of time covered by the reigns of Henry IV., Henry V., and Henry VI.

The semi-fortified houses of this latter period form a class by themselves, and stand on a border-line between the grim fortresses of an earlier time, and the palatial structures of the stately days of Elizabeth.

For the most part, this "new style" of building was done to the order of noblemen who had won their spurs in the French wars.2 Brickwork was employed, not because there was any scarcity of stone, but because it more nearly reproduced French chateaux, with which their exploits had made them familiar.

The words "new style," when applied to these brick houses must, of course, be understood in a restricted sense, for brick building had been carried on sporadically in England ever since the Roman occupation. Even as long ago as the days of Noah, the plain of Mesopotamia was famous for kiln-burnt bricks,3 as Egypt was for sun-dried bricks;4 while Nebuchadnezzar, probably the greatest builder the world has ever known, had used bricks for the rebuilding of Babylon more than 2,000 years ago.5

One of the foremost among the warrior-statesmen builders was Baron Cromwell. The work done by him is interesting from an architectural point of view, (firstly) because of its influence upon local architecture, (secondly) because we know something about the men who were actually engaged upon the work.

Before we consider his building schemes in detail, a brief outline of the life and time of this local patron of architecture may not be out of place.

In the year of our Lord 1394,6 a son and heir was born to Radulphus Cromwell, lord of the manors of Cromwell and Lambley—two unimportant and little known villages in the county of Notts. History does not record where the auspicious event took place. Presumably it befell in the old manor-house at Lambley; for it is a fair assumption that "the house which had mothered him when in his cradle" would be in his mind when, near the end of his life, he framed a codicil to his will, wherein "he directs the church & chancel at Lambley in this county to be rebuilt from his estate, and directs two images to be placed upon the tombs of his father & mother in that church."

The old manor-house at Lambley, in which a long succession of Cromwells had lived, has passed almost beyond recognition. A portion of the old foundation walls is incorporated in the rectory, which now stands upon the site. Indications of the moat may still be seen in the rectory grounds; and depressions in a field to the eastward mark the position of the old stew-ponds, etc. (July, 1914).

Like his father before him, the new-comer received the Norman name Radulphus—a name borne by his predecessors through many generations. The founder of the family, one Alden (or Haldoen), appears to have settled in the district soon after the Conquest, taking his surname (Haldoensis de Cromwell) from the village of Cromwell, situate on the left bank of the Trent, five miles below Newark.

Alden was succeeded by Hugo, and then followed an unbroken succession of Ralphs.7 Thoroton says "they were all Ralphs downward to the last (the tenth, or possibly the eleventh) who was Ralph Lord Cromwell of Tateshall, who was constituted Lord Treasurer 11. Henry VI;"he also adds, "they were sometimes called of Lambley" (p. 281).

As years rolled on, large estates accumulated in the hands of the family, so that by the time the subject of our notice had reached his prime, he was not only lord of the manors of Cromwell and Lambley, but also third Baron Tattershall of Tattershall, Lincs.; a person of importance in the government of the day, and the owner of broad acres in many shires. So exalted, indeed, was his position, that when he journeyed from his country seat to London, "he was accompanied by a retinue of 100 horsemen " (William of Worcester).

Writing of this period in his Short History, John Richard Green says:—"the Parliaments, which became mere sittings of their retainers & partisans, were like armed camps, to which the great lords came, with small armies at their backs."

The times in which he lived were stirring and eventful. Born during the reign of the last of the Angevins (Richard II.), he saw that monarch deposed in favour of Henry IV., as the result of a Lancastrian revolution. He took an active part in the conquest of France under Henry V., and was present at the taking of Caen, Courtonne, Chambray, etc., in 1418. On his return he had a share in the government of the country, being appointed (in 1422) one of the five lords who formed the Council to act with Gloucester during the minority of Henry VI.

On his appointment as Chamberlain he won golden opinions "on account of his wisdom, & especially with regard to his money making craft" (Hardyng). In 1433, he was appointed Lord Treasurer of the Kingdom, an office which he held with distinction for ten years.

It was during this period that his chief building schemes were carried out, but alas! no sooner was Tattershall completed than storm-clouds broke over the land in the Wars of the Roses.

William of Worcester tells us (pp. 770, 771) that the first act in that grim tragedy occurred at Tattershall when Cromwell's niece was married to Thomas Neville in 1453. A quarrel arose between Neville and Egremont which eventually set all the nobility ablaze; the Duke of York taking sides with Neville, the Duke of Exeter with Egremont. Cromwell's participation in the internecine strife which ensued was but of short duration. Being by this time an avowed adherent of the House of York, he joined forces with the Duke of York and others who took arms against the king. According to the Paston letters, Cromwell did not come up in time to take his part in the first Battle of St. Albans, May 22nd, 1455, when the king was taken prisoner and Protector Somerset was slain. He was consequently suspected of lukewarmness in the cause, and when dissensions broke out among the triumphant Yorkists, he was openly accused of treason by Warwick.

Four months later, further misfortune overtook him in the death of his wife, and after another four months of bereavement and sorrow, Cromwell breathed his last on the 4th of January, 1456. Being childless, his two nieces, Joan and Maud, became his co-heirs. The first husband of Joan was slain at the Battle of Barnet; the second husband of Maud (Thomas Neville) fell at the Battle of Wakefield, while her third husband (Sir Gervase Clifton) was killed at Tewkesbury. Thus ended the long line of Cromwells, Lords of Tattershall and Lambley.

The Tattershall estate was brought to Cromwell's family by the marriage of his grandfather with Maud, daughter and sole surviving heiress of Sir John Bernak and Joan his wife, daughter of the second Baron Marmion. This was the second time that alliance had been made between these two families; for in the 13th century Ralph Cromwell, Lord of Lambley, had taken for his second wife Mazera, the second daughter and co-heir of Philip de Marmion, Lord of Tamworth.

A stone-built castle, erected A.D. 1230 under license from the king (Henry III.) still occupied the moated site at Tattershall. This was found to be too unpretentious for a baron who was destined to become the Lord Treasurer of the kingdom; and further, the knowledge that many of his comrades were building new houses for themselves inclined him to emulation.

The ancient stronghold was demolished, and in its stead arose a new dwelling, designed after the manner of buildings made familiar to him during the campaign in France, and executed in like materials. The work was commenced in 1431, and after eighteen years of patient and continuous labour, the workmen succeeded in raising one of the finest examples of mediaeval brickwork in the kingdom.

If we may rely upon Buck's drawing of 1726. the old hall and portions of the domestic offices were fitted with new windows of the Wingfield type, and incorporated with the new work; that the keep was superimposed on old foundations is certain, for during the recent restoration, the base of an old curtain wall and two round towers was brought to light.

The bricks, which are slightly smaller in size than was usual8 (average size, 8½in. by 4in. by 2in.), are popularly supposed to have been brought from Flanders, but this was not the case, as the number of pebbles and fossils which they contain indicate that they were made from local clay. They are laid in old English bond, i.e., the bricks in one row are all laid lengthwise, and in the next row endwise, as distinguished from Flemish bond, wherein they are laid one lengthwise and one endwise alternately in each course. The hard-burnt dark coloured bricks, which had been in contact with the flame while in the clamp, are utilized to form diamond patterns in the external walls. Lincolnshire stone is sparingly used for dressings to windows and doors, and also for the parapet copings, although in some cases these latter have been renewed with cement.

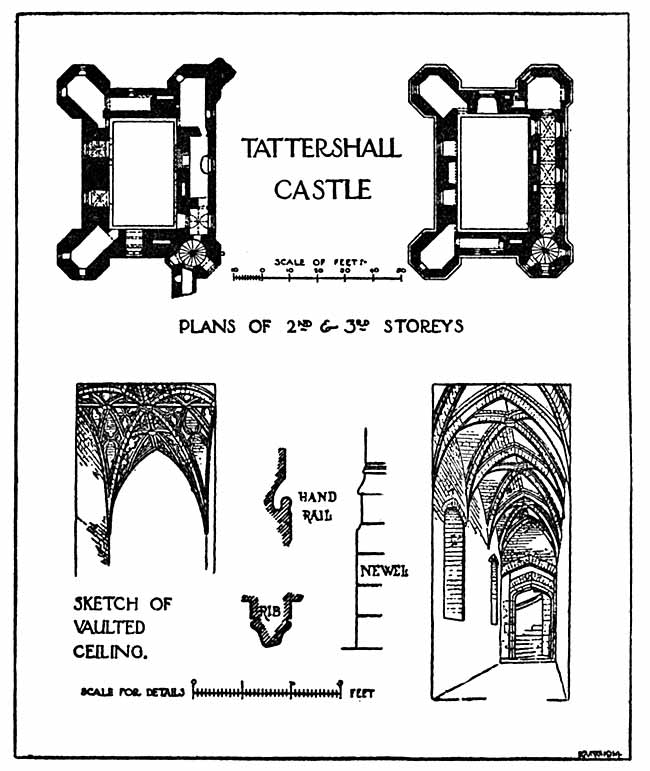

Like most other brick houses of the period, the chief feature of Tattershall was a huge tower or keep, dominating a moated enclosure, which also contained the domestic and subsidiary offices. With the exception of the guard-house, and the ruined dwelling of the Master of the Horse, the keep is the only ancient work now remaining. It is 87ft. long by 69ft. wide, and has an irregular polygonal turret at each angle. The height from the ground to the parapet of the turrets is 112ft. Originally the turrets were roofed with octagonal pyramidical spirelets,9 having fleur-de-lys finials, but these have all been removed.

The enormous number of bricks used in the construction of this keep may be realized when we consider that the eastern wall is 16ft. thick at the base. This wall, however, is not solid throughout, for it contains a passage or gallery of communication, running the whole length of the main apartment, 6ft. 2in. wide on the first floor, and 5ft. 7m. wide on the second floor.

The ground floor of the tower was the hall of state (38ft. long, 23ft. wide, 17ft. high). Above this was an audience-chamber on the first floor, a drawing-room or state-bedroom on the second floor, and a large chamber on the floor above. The floors were made of plaster carried on timber. Each of the main floors was supported on four massive oak beams.

Altogether, the house part contained forty-eight separate apartments. William of Worcester records "that the household consisted of 100 persons, that the annual expenditure was about £5000, and that the cost of building the principal and other towers was above 4000 marks."

The windows are of varying height and design. They are scarcely appropriate to a fortified house, being more in conformity with the current style of English church architecture. Nevertheless, the building bears a closer resemblance to a French chateau than to an English castle.

A glance at the battlements will show whence this impression arises.

No sooner has a great battle been won, than mementoes of it appear in the homeland, if it be only in the name of a street or a house. It was so in this case. At the siege of Carcasonne, the English found the castle walls bristling with "hourdes," i.e., timber barricades, made removable when not in actual use, from whence missiles could be discharged. Our modern word hoarding comes from the same root. At Tattershall, the "hoarding" idea is introduced, but here it is carried out in brick and stone. A covered gallery, pierced with loopholes, and partly projecting over the machicolations of the walls, extends from turret to turret. This would enable the defenders to shower stones, boiling oil, or molten lead upon the heads of the attackers beneath; for until "villainous saltpetre" caused fighting at close quarters to become unpopular, it was customary to greet the manipulators of battering rams and scaling ladders with "something humorous" of this sort.

Bear in mind that all this happened 500 years ago. The apostles of "Kultur" have outgrown such crude methods. It is true that boiling oil is still sometimes ejected, but asphyxiating gas and vitriol are considered to be more refined.

Owing to the rapid development in methods of warfare, there never was much prospect of the battlements in this case being used for such a purpose, and we must conclude that they were introduced more for ornament than for actual use. Nevertheless, each of the four turrets was provided with a fireplace, on which to prepare the "ingredients," if necessary, as well as to give warmth and comfort to the watchmen on the walls.

A circular staircase is contained in the south-east turret. It is 4ft. 4in. wide, and winds round a stone newel, 7½in. diameter. It has a moulded stone hand-rail ingeniously sunk in the wall— a detail common to all the brick houses of this period. This was the only means of communication between one floor and another and with the battlements, for the staircase, as an essential feature in the home, had not yet assumed the importance it was shortly to attain.

The corridor connecting the staircase with the rooms on the second floor has a vaulted ceiling, executed in brickwork. The carved stone bosses at the intersection of the ribs bear heraldic shields.

The vaulting to the third floor corridor is further enriched with tracery and cuspings in cut and rubbed brickwork: but it should be noticed that the "tuck pointed" joints have been put on over a thin skimming of coloured cement, and do not correspond with the actual joints in the brickwork beneath, and the heraldic bosses at the intersections are moulded in plaster.

The most interesting architectural feature of the interior is the series of fine stone chimney-pieces in the four main apartments. They are essentially English in design and execution, and their influence is still manifest in modern work. They are said to have been taken as models by Pugin, when he designed the internal decoration of the House of Parliament at Westminster.

From the profuse display of armorial bearings, we are able to fix the date of erection with precision, for the predominant symbol—the treasurer's purse with the motto, "N'aj je le droit" ("Have I not the right")—fixes the date during Cromwell's term of office as treasurer (1433-1443), while the arms of Cromwell and Tattershall impaling D'eincourt, could not have been used before his marriage with Margaret D'eincourt, nor after his death, seeing that he left no issue.

The chimney-piece on the ground floor10 has a crocketted ogee arch, which runs up into the cornice, and encloses a shield bearing the arms of Cromwell (Argent, a chief gules, over all a bend azure). The frieze is divided into eighteen panels, wherein are displayed the Tattershall alliances and the arms of former owners, alternating with the Lord Treasurer's badge. Reading from left to right, the arms are:—

Top Row.

1—Cromwell (ancient).—Gules, ten annulets or (Richard II.).

3.—De Albeney.—Gules, a lion rampant or, armed and langued gules.

5.—Marmion.—Vair, a fesse gules.

6.—Bernake.—Ermine, a fesse gules.

8.—Cromwell and Tattershall (chequy or and gules a chief ermine) quarterly, impaling D'eincourt.

10.—Cromwell and Tattershall quarterly.

Bottom Row.

12.—Cailli.—Bendy of eight. By error on the part of the mason, this is here represented bendy of ten. In this instance, as in many others, the skill of the craftsman exceeded his knowledge, to the confusion of the heralds.

14.—D'eincourt.—Argent, a fesse dancetty between ten billets or.

15.—De Driby.—Argent, three cinquefoils and a canton gules.

17.—Grey of Rutherford (Rotherfield).

The chimney-piece on the first floor is treated with great freedom and fancy. It has a continuous row of circular panels in the frieze, the first and last of which contain a fanciful representation of the treasurer's badge.

2 is the Tattershall shield.

3 a representation of St. George or St. Michael and the dragon.

4 the marriage shield, Cromwell and Tattershall, impaling D'eincourt.

5 on a couche shield, with hairy wild men as supporters, Cromwell and Tattershall quarterly.

6 a representation of a man and a lion (probably a representation of a feat said to have been performed by Hugh de Neville, the Crusader, who, on being attacked by a lion, tore it asunder by sheer physical strength: but the meaning is now obscure).

7 the D'Albini lion.

There are some very quaint little figures and devices in the spandrils of the four-centred arch, and also between each circular panel, which should not escape notice.

The treatment of the chimney-piece on the second floor is very chaste and delicate, and quite characteristic of the period. The badge is again displayed alternately with tiny shields bearing Bernake, D'eincourt, Driby, Cromwell, and Tattershall.

A somewhat similar treatment occurs in the room above, but the division of the frieze into small cusped panels is not quite so pleasing in effect. The badge, of which the treasurer must have been inordinately proud, occurs again in the spandrils of the four-centred arch, and in the frieze alternatively with D'eincourt, Driby (illegible), Cromwell, and Bernake.

Each chimney-piece has an embattled cornice, the large hollow in the moulding being enriched with "four-leaf" ornaments, grotesques, and single roses with five petals; the latter being the white rose ensign of the House of York, whereof Cromwell became an avowed adherent.

It will be remembered that in September, 1911, an attempt was made to transport this famous landmark of the Fens across the Atlantic, and to rebuild it on American soil. The chimney-pieces, said to have been sold for £2,800, had already gone as far on the way as Tilbury Docks, when Earl Curzon intervened and prevented their shipment. Under his care all the fireplaces have been repaired and replaced in their original positions (June, 1912). By the end of the year 1914, the keep, guard-house, and moat had been carefully restored by him, and protected against possibility of further damage; for which service all true lovers of antiquity will desire to tender their grateful thanks.

(1) Extract from a "license to crenellate," issued to Sir Edmund Bedingfeld, A.D. 1482, " that he according to his will & pleasure may build, make, & construct walls and towers with stone, lime and gravel, around and below his manor of Oxburgh, in the County of Norfolk, and enclose that manor with walls and towers of this kind; also embattle, crenellate, & machicolate those walls & towers."

(2) Tattershall Castle, Lines., built by Baron Cromwell, 1433. Heron Gate, Essex, built by Sir John Tyrrel (d. 1437). Falkbourne Hall, Essex, built by Sir John Montgomery (license 1439). Hurstmonceaux, Sussex, built by Sir John Fiennes, 1440. Caistor Castle, Norfolk, built by Sir John FalstafI, 1459. Middleton Towers, Norfolk, built by Lord Scales (d. 1460).

(3) "Go to, let us make brick, and burn them throughly. And they had brick for stone, and slime (pitch) had they for morter."—Genesis, xi., 3.

(4) Exodus v. (2) 604-561 B.C. Every brick was stamped with the name and lineage of a king.

(5) Some authorities give the date 1403: but this is due to an error in Inquisitions post Mortem, 7 Henry V., where his age is given as 16 when his grandmother died in 1420; whereas it should have been given as 26.

(6) Testamenta Eboracensia, vol. ii., pp. 196, 197, etc. Will dated December, 1451. Codicil, Michaelmas Day, 1454.

(7) The growing importance of the family is indicated by the fact that the sixth Radulphus de Crumwelle was " included in a muster of the flower of Notts gentry, being summoned to perform military service in person with horses & arms in Scotland." 1297.

(8) The average size for the period was quite 1in. longer and ¼in. thicker than the Tattershall bricks. It is not known where these bricks actually came from; most probably it was the Isle of Ely, as bricks were being made there at that time.

(9) Buck's engraving of 1726 shews the roofs on all the four turrets, and early photographs shew a roof still standing on one of them.

(10) See Transactions, vol. xiv., 1910, for illustrations.