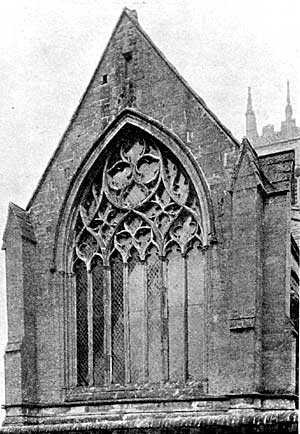

PLATE III. Hawton church.

Having been introduced into window design, sculpture rapidly became popular, and thenceforward it was no uncommon thing for a tabernacle, or niche for an image, to be incorporated not only by the side of the window, but sometimes as part of the window itself. One such example, at any rate, may be seen in this county in the east window of the north aisle at Fledborough, where Sir John de Lysius obtained sanction (c. 1340) to found a chantry at the altar of the Blessed Virgin, in the parish church, which had recently been rebuilt. It is a beautiful window of three lights, with flowing tracery in the arched head. The central opening is occupied with a stone canopied niche, which presumably once contained an image of the Virgin. The 14th century glass is still preserved and is perhaps the best example of mediaeval glass in the county. (Vol. XI.).

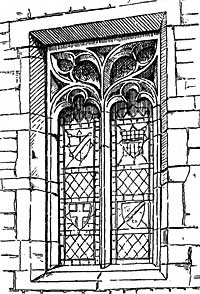

An earlier example is found at Thurgarton, but in this case the window has been removed from its original position and re-set in the east wall of a new chancel. Here the canopied niche is placed in the wall space between twin-windows of geometrical type, each having two lights with quatrefoil tracery in the head.

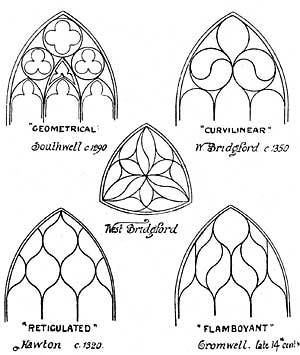

Curvilinear tracery, as the term suggests, is tracery bounded by curved lines. It is also called "flowing" tracery; because the vertical line of the fillet on the mullion branches to right and left, on reaching the sub-arch; and continues to ascend through all the ramifications of the tracery, as a continuous flowing line without a break. (See diagram, West Bridgford). It reached its zenith in the middle of the 14th century, and was prevalent throughout the county. It is seen in the windows of Cromwell, East Stoke, Flintham, and West Bridgford (Vol. XIX.), but perhaps to best advantage in the beautiful chancels at Arnold, Car Colston, Sibthorpe, Hawton (Plate III.), and Woodborough (Vol. XII.) The east window at Hawton (c. 1320), oft quoted as a typical example, comprizes seven lights—three in the central division and two in each of the side divisions. The main lines of the tracery are thus made to assume the form of two ogival arches, whose sides are unequal. The general effect, in my opinion, is distorted and not at all pleasing; but it is obvious that the balance would be restored if the number of lights was increased to nine. At Woodborough (c. 1356) (Plate IV.), and Car Colston, the same builders adopted a five-light division; but the defect is still noticeable, although not to the same degree.

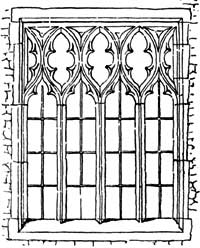

Diagrams of Decorated tracery.

The difficulty of dealing with subdivided arches, no matter how numerous the lights, was successfully overcome by a favourite design much in vogue at this period, known as "reticulated" or net-like tracery. No matter whether the arched or the square-headed form of window was adopted, no matter how many subdivisions were required, no difficulty in setting out was presented; as every part consisted of an ogee arch, or part of an ogee arch. For the same reason, it was easy to glaze. It is found in a large number of our village churches—at the end of the aisles, at Stapleford, Annesley (Vol. XVI.); in the side walls of chancels, at Hawton (see diagram), Arnold, Woodborough, Car Colston (Vol. I.); and sometimes at the east end of the chancel, as at East Leake. It was in vogue for upwards of half a century (c. 1310-1370).

The idea of merging the vertical lines of the mullions into the curved lines of the tracery without a break in direction, sometimes produced long flame-like compartments in the tracery. This is classified, therefore, under the French term "Flamboyant." Windows at the east end and south side of the chancel at Cromwell (see diagram) and at East Stoke, Car Colston, and Flintham, come under this designation.

It was no uncommon thing in some districts for the windows of the early 14th century to have the hollows of their mouldings both within and without, studded with ornaments; a series of "ball-flowers" or "hawk-bells," as they are sometimes called, or flowers of four petals arranged at equal distances from each other.

Examples of the ball-flower enrichment are to be found on towers in this county, as at Scarrington, but I have not yet found a window so decorated.

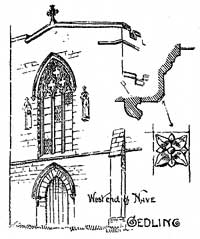

West end of nave, Gedling.

Square-headed window, Nuthall.

From north wall of old nave, West Bridgford.

A "net tracery" window at the west end of the nave at Gedling (c. 1320) has the four-leaved flower on the jambs and the arch. The niches on either side of this window once contained images of SS. Peter and Paul, the patron saints of the convent at Shelford, whose canons had the right of presentation to the vicarage.

Contemporary with arched windows not of this type, but even more in vogue, especially in the flank walls of aisles, were square-headed windows. It would be a simple task to give a list of churches in this county where square-headed windows of Decorated type are not to be found, so general was their adoption. But, strange to say, their use is almost confined to this locality; for examples are not so generally met with outside the county. The illustration from Nuthall shews the most frequent type; but great variety of treatment is displayed both with regard to the number of lights, and the design of the tracery; (see the illustration of a beautiful little window on the north side of the chancel at Rolleston Vol. XVII., and the four-light window from the north wall of the old nave of West Bridgford parish church). This window head is still preserved in the north wall of the new vestry of the enlarged church.

By this time the glass painter had come fully into his own.

"Wyde wyndowes ynwrought

Ywryten full thicke,

Shynen with shapen sheldes

To shewen above.

With merkes of merchantes

Ymodeled between."—

Piers Ploughman's Crede (temp. Richard ix.)

Such work was rapidly giving place to pictorial representations. While cusping was admittedly very beautiful when seen from without, it was not so effective when seen from within; and seeing that the field for the glass painter, was too much cut up by cusps and points to admit of figure subjects being displayed to advantage, a change set in in favour of Rectilinear tracery, i.e., tracery bounded by straight lines; for, whereas in the former style, the vertical lines of the mullions were fused into the curved lines of the tracery, in this style, the vertical lines of the mullion were continued upwards between the sub-arches, until the containing arch was reached; and numerous other vertical and horizontal lines were also introduced.

Nearly every village church can shew an example of the Rectilinear or Perpendicular style of Gothic architecture. It prevailed throughout the 15th century, and as a clerestory became a necessity during that epoch, even churches of otherwise early date will often contain Perpendicular work in the clerestory; while not a few chancels, and in some cases, the entire church was rebuilt in the 15th century. The church of St. Mary, at Nottingham is a good illustration of a rebuilt town church, and St. Giles, Holme, near Newark (Vol. IX.), of a village church; while Sutton-on-Trent (Vol. VI.) shews an added clerestory and side chapel in the Perpendicular style. The east windows at Nuthall and Bilborough are also good examples of the style.