The Autumn Excursion.

A MEETING of the Society was arranged for the afternoon of October 4th, 1916, at the Church of St. Mary, Nottingham, by kind permission of the Vicar, Canon Field. The Rev. A. Du Boulay Hill, with the help of Rev. A. M. Y. Baylay, undertook the task of preparing an account which was read in the Church. This is supplemented by a paper on some architectural details by Mr. Harry Gill, and by notes on the Regimental Colours preserved in the Church.

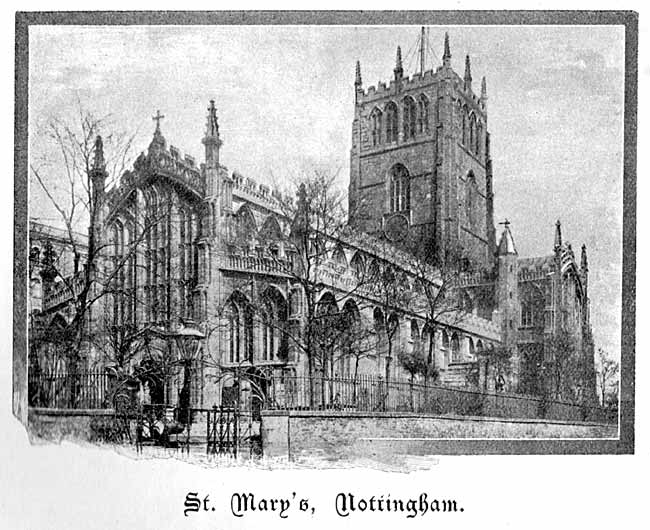

THE CHURCH OF ST. MARY THE VIRGIN, NOTTINGHAM.

By The Rev. A. Du Boulay Hill, M.A„

October 4th, 1916.

The fine church of St. Mary the Virgin, in which we are assembled, stands before us as the shell of a typical town parish church of the last quarter of the 15th century, for it can hardly have been fully completed until that period. The imagination must picture it with its great rood or crucifix, standing upon a loft over a screen across the western tower-arch and extending to the turret stairways on either side; another screen, or pulpitum, across the eastern tower-arch enclosing the chancel; its transepts divided by screens into various chapels for the gilds which played such an important part in the religious life of those times, with tombs of worthy citizens erected alongside of the altars in the chapels they had endowed or to which they gave special devotion; its windows glowing with the heraldic record of the armorials of its benefactors.

All this internal equipment has passed away, and the work of the antiquary is to trace the steps by which the church reached its present condition, a task which presents many problems difficult to solve in the absence of documentary evidence.

We know little or nothing of the building, or succession of buildings, which previously occupied the site of the present church. One Nottingham church only is mentioned in the Domesday Survey. The great Cluniac Priory of Lenton, founded twenty years later, dominated the ecclesiastical life of Nottingham, and all the three ancient parish churches are included in its charter of endowments; St. Peter's and St. Nicholas' being in the patronage of the Priory but not impropriated. The founder of the Priory, William Peveril, gave to the Prior and Convent "the Church of St. Mary in the English borough with all its appurtenances" in 1108; but there is no direct evidence that the Priory exercised the rights of patronage at first; perhaps Papal claims interfered. In 1234, Gregory IX commissioned "the abbot and prior of Stanlaw in the Diocese of Coventry to induct the prior and convent of Lenton into corporal possession of the Church of St. Mary, Nottingham, granted to them by the Pope on resignation of his nephew Nicholas, subdeacon and Chaplain, a Vicar's portion being reserved."1 From this time the prior and convent of Lenton exercised their right of presentation to the Vicarage, until the dissolution of the Priory, when it passed into lay hands.

Late Norman capitals.

The church was damaged or destroyed by fire on three occasions: 1140, 1153, and 1174, in the troubled days of Stephen and Henry II.; and evidence of an aisled church, built about 1175, was afforded by the discovery of two late Norman capitals, found and buried again in the rebuilding of the tower piers in 1843. Sketches of these capitals, made by Sir Charles Robinson at the time, were given in "Notts, and Derby Notes and Queries," 1894. By the kindness of the editor I am enabled to reproduce them here. Some fragments of an early 14th century column with filleted mouldings, now visible by removing a section of the flooring beneath a pier of the north arcade (second from the crossing) indicate some rebuilding of that date, but give no evidence of the size or position of the church of that period, as they are not in situ. Several floor stones with incised crosses of this and earlier dates may be seen forming the bench-table along the walls of the aisles.

We now come to the building of the present edifice, the story of which, in the absence of historical records, is mainly to be gathered from the evidence of the stones themselves. The religious revival which followed the terrible visitation of the "Black Death" in 1349, no doubt stirred the parishioners of St. Mary's, and made them feel that their church was too small and inadequate. The gild of All Saints was founded before 1375, and the gild of Holy Trinity in 1395, which perhaps gave the impetus to the renewal of the church. A great scheme for a new and larger building was set on foot, supported probably by the families of Tannesley, Samon, Plumtree, and Alestre, merchants of Nottingham, by Thomas de Arundel, Archbishop of Canterbury, formerly of York, and Lord Chancellor, the Nevills, and perhaps King Richard II. himself, if we may judge by Thoroton's account of heraldic glass existing in his time.2 In 1401 the work was in progress, as shown by the following grant from Pope Boniface IX.3 "An Indulgence during ten years to penitents who on Sunday next before the Annunciation and the Sunday next after Corpus Christi visit and give alms for the fabric or conservation and repair of the parish church of St. Mary the Virgin Nottingham in the Diocese of York which has been newly begun with solemn wondrous and manifold sumptuous work, towards the consummation of which a multitude of workmen with assiduous toil fervently strive daily. All the oblations are to be converted to the utility of the said church."

This document obviously quotes the language of a petition which came directly from Nottingham. The work had been begun before August, 1401, and was in need of funds.

What was the "sumptuous work" which was then in progress? It is quite probable that the foundations of the new building were set out as far as possible entirely outside the old church. The transept ends, with the two turret stairways, the walls of the north and south aisles, and the west end extending 35ft. beyond the old church, were begun and carried up at least to the level of the window-cills. It is evident that in this case means of access to the existing church within must be provided, which should correspond to the position of the original entrances. There was therefore a good reason for the completion of the south porch which we see to-day as one of the earliest parts of the new work, perhaps from the benefaction of John Samon. His tomb, constructed at the same time, at the end of the south transept which we shall notice hereafter, exactly corresponds with the work of the porch. The west front has a central porch with similar foliated arch and panelled gable. This is of course entirely modern, but it reproduces the appearance shown in Thoroton's view of St. Mary's in 1667, giving the west porch as part of the undoubted scheme of the whole church.

Since the old nave was so much shorter, it may also have been narrower than the new one; but it is of course possible that the north and south aisle walls were rebuilt on the line of the old foundations and not outside them, in which case the porch would be actually on the site of the old one, and the former church would be of the same width as the present. This is somewhat corroborated by a difference to be noted externally on the north side between the two western and the four eastern bays; the windows of the former having a roll-mould continued down between each pair of windows. This is absent from the four eastern bays, which were probably the last to be erected. In any case the position of the south porch is clear evidence that the church was lengthened considerably to the westward. (See the Plan, page 52).

Nave and north transept.

I think the work was interrupted before it had gone very far. Perhaps the funds were not sufficient, and the builders hesitated before clearing away the old church in which the services had been all along continuously maintained. It was not until the latter part of the 15th century that the arcades, clerestory, and central tower could have been begun and carried up from the ground, and the whole church brought at last to completion in all its parts.

The piers of the arcades, lozenge-shaped in plan, with the shorter diameter between the arches, and shallow arch-moulds carried down without capitals, suggest a date of about 1470-80, and cannot be ascribed to any time much earlier than that period. The pier section is reproduced in miniature in the central mullion of the aisle-windows in each bay, and the sunk chamfer moulding is characteristic of the whole of the nave and transepts above the window cills.

The central tower belongs to the same late 15th century date. It was intended to be vaulted in stone at the crossing, as shown by springers at the angles. Settlements in the tower-piers, however, towards the west, south, and north, soon began, and the slender arcade of the nave afforded no sufficient abutment for the weight of the tower. In consequence the transept walls have become curiously distorted, and the ends of both transepts and nave were thrust outwards, so as to require much rebuilding in later years. The first part to give way would be the vaulting of the crossing, which, by its fall, probably gave rise to the legend of the collapse of the tower in the storm in 1558. The present vaulting in wood was erected in 1812 by Mr. W. Stretton.

(1) Papal Letters, Vol. 1., page 140.

(2) See a paper by Thomas Close, F.S.A., Allen's handbook of Nottingham, 1866

(3) Papal Letters, Vol. V., page 443. 1401 Kal. Aug.