Architectural Notes on The Church of St. Mary the Virgin, Nottingham

Contributed by Mr Harry Gill.

THE story of the architecture of the mother church of the ancient town of Nottingham is no less charming than the story of its antiquity and associations.

From its proud position on the edge of the sandstone cliff it still dominates the older parts of the town, and fills the beholder with reverence and admiration. The skill of the mediaeval craftsmen who conceived and executed this fine example of "the Indian summer of Gothic architecture" calls for more than passing notice; for whether we regard it with a critical eye and make comparison between its component parts — which, although the work of more than one generation of craftsmen are sufficiently similar to be harmonious, while being sufficiently diverse to excite interest — or whether we take a general view of the composition as a whole; we shall surely derive nothing but pleasure and satisfaction.

And especially must this have been so, nearly four centuries ago, when the sacred pile, the acropolis as it then was of the ancient town, was pronounced by an itinerant critic to be "excellente [new] and unyforme yn worke and so maine faire wyndows yn itt yt no artificer can imagine to get more." (Leland, 1534).

A chronological description of the architecture of the present edifice is now rendered difficult, not only by the paucity of records, but even more so by the frequent renewals of masonry without respect to the old landmarks.

The tracery throughout the whole range of clerestory lights was entirely replaced in 1843, when a new roof was put upon the nave, the south porch and the aisle windows have been patched again and again with new stone, and even in some cases with Roman cement, the large window at the end of the north transept became a plain "Puritan" window for a time by the removal of all the tracery and cusps, and the external wall faces have been cased and recased until no reliable theory can be based on isolated details.

But if indeed the fabric generally retains the semblance of its pristine look, its stones may still be read like the pages of a book.

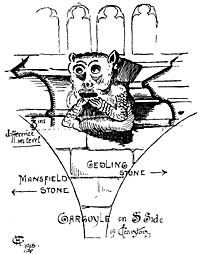

One feature, happily, still remains unaltered, and this may possibly supply a key to the whole fabric. A huge gargoyle—the only one on the "body" of the church—projects from the parapet of the south clerestory, between the second and third bays from the crossing. The reason for this is not far to seek, for it occurs at a point where there is a break of three inches in the line of the cornice, and a perceptible change in the contour of the moulding. It is therefore obvious that it was inserted to mask the junction between the work of two distinct periods, for eastward of the gargoyle the work is executed in Gedling stone, and westward of it Gedling stone is used below the line of racking, magnesian limestone above it.

This then will be a starting point for our inquiry.

It is clear to the student of architecture that the earlier work is all to be found on the eastward side of the gargoyle; that a portion of the south aisle including the porch, the eastern bay of the north aisle including the chantry-house doorway, the lower portion of the transept walls including the canopied tomb on the south side, and the two stairway turrets, are contemporaneous, while their details—the panelling in the gables and buttresses and the predominance of foliated ogival arches—are eloquent of the closing years of the 14th century.

Clerestory (south side).

South porch.

A foolish theory has been promulgated that the south porch was brought here from the Priory of Lenton on the dissolution of the monastery in 1538. This idea probably arose from the fact that among the delicately carved ornaments in the hollow of the cornice, there are two demi-angels clothed in albs, each holding a shield, in the manner in which the arms of the Priory were wont to be displayed; but whether they ever held the blazon or not it is now impossible to determine, (quarterly or and azure over all a cross calvary sable fimbriated of the first). This device occurs again on the western portal [rebuilt in 1843] and is also found on many other churches that were under the patronage of the Convent, [Beeston for instance]. In addition to the angels with shields, the carvings comprise "four-leaf" flowers, rosettes, lion's faces, and grotesque masks of late Decorated type. The lion's faces especially are vigorously carved. This was a favourite subject, often used as a "powdering" during the reign of Richard II. It was also used for the attribute of St. Mark, or St. Jerome, or for the Zodiacal sign governing the month of July.

The reason for the anomalous position of the south porch will be referred to later. Thoroton and other writers have described the ancient glass in the south aisle as containing the arms of Samon, Archbishops Arundel and Nevill, and King Richard II. This glass has all been destroyed, presumably when the new tracery was made in 1761; it is mentioned here as a further proof that the earlier portion of the existing work was executed during the reign of Richard II.; for if the canopied tomb in the south transept is the memorial of John Samon the elder, a former Mayor of Nottingham in 1361 and onwards, who died c.1395, or of his son, whom Thoroton styles John Samon "the Benefactor of St. Mary's," who died in 1416 (and there is no incongruity in suggesting that the tomb might have been set up during the lifetime of either of them), then it follows that all the earlier work, which corresponds with the tomb in material, in details, and in the mode of working, is part of one and the same scheme.

A paragraph in the Borough Records, under date October 1393 [Vol. 1. p. 252] seems to imply, that the west front of this scheme for a church only four bays in length, was completed, or at any rate nearing completion, in "the 16th year of the reign of King Richard the Second," when John Painter of Nottingham claimed a sum of two shillings of silver "pro pictura unius bell' crucifixi super corneram Ecclesiae Beatse Marise villae Notyngham."

This sentence has unfortunately been translated "for the painting of a bell of the cross, &c., &c.," which does not convey any intelligible meaning, whereas a better translation would have been "for the painting of a handsome rood (or crucifix) over the corner [stone] of the church of Blessed Mary, &c." This is intelligible, as an external crucifix is known to have been set up, near to the entrance of other mediaeval churches. For instance, there is a life-size sculptured crucifix on the external western wall of the south transept of Romsey Abbey, near to the nun's door. This is early Norman work, and was probably taken from the interior of the nave.

The scheme thus "newly begun with solemn, wondrous and manifold sumptuous work," was not allowed to stop on account of the death of a benefactor. The Indulgence of 1401, quoted in extenso by the Rev. A. Du Boulay Hill in the previous paper, probably caused money to flow in to such an extent, as to warrant the enlargement of the original scheme to a church of six bays in length, instead of four. The Wills1 of prominent citizens who died early in the 15th century shew that considerable sums of money were left for this purpose.

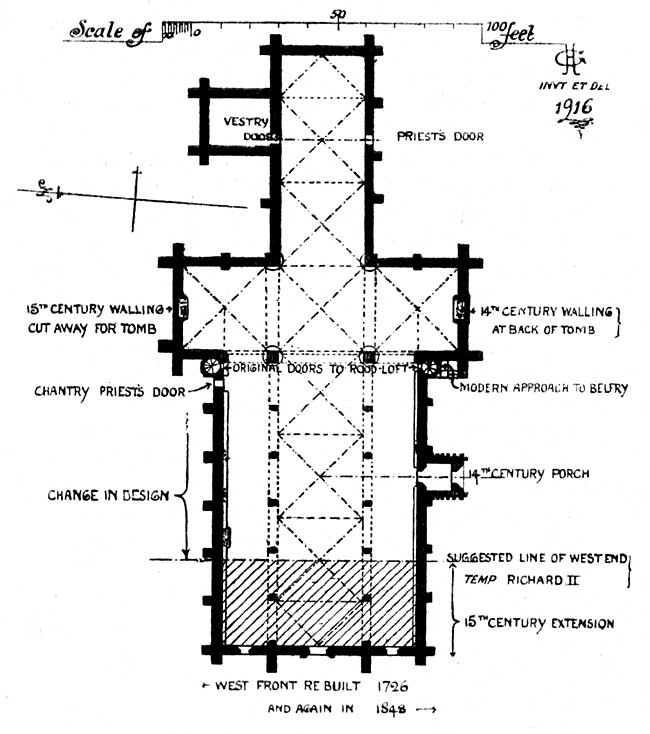

While the old west front was yet standing, the aisles were extended westward by two bays, and a new west front was erected. The earlier south porch would consequently be the means of entrance during the period of enlargement, and it was ultimately allowed to remain as we see it to-day, incorporated in the new works, despite its unusual position in regard to the extended nave. A glance at the diagram plan will make the position clear.

Plan of St Mary's church, Nottingham.

The earliest published view of the extended church [Thoroton's History of Notts. 1677] shews a western portal which is so analogous to the south porch, that it must either have been specially designed to harmonize therewith, or, as seems to me more likely, it was the western portal of the earlier, or Samon church, which had been carefully taken down and rebuilt in the new position.

Blackner in his History tells us that the whole of this west front was destroyed and replaced by a new front of classical design in 1726; this in turn was removed in 1843, when an attempt was made to reproduce, the original design; and this is why the present western portal, the central feature in a 15th century design, is noticeable for its 14th century detail.

It is not safe to attach too much importance to old engravings, but it is not without interest to notice, in passing, that in the present west front as reconstructed (1843-8), the central window of twelve lights, i.e., of three divisions of four lights each, is flanked by two windows in the west end of each aisle, as was the case in the classical front of 1726 which it replaced; whereas Thoroton's view of the 15th century west front shews but one. Keeping in mind the predominance of even numbers throughout the design, I think the view unreliable on this point.

Extracts from the Borough Records [quoted in the previous paper] shew that building operations were in progress between 1386—when a Commission of Inquiry, which had assembled on the morning of October ist, had to adjourn at noon to the conventual church of the Grey Friars in Broad Marsh, "for the better expedition of business"—and 1517, by which time the Rood, the last item of the furnishing, was completed. The alleged theft of a bell-clapper by the sub-clerk, referred to under date 1395, seems to imply that at that time the steeple had been taken down as a preliminary to reconstruction and enlargement. Whether this was a central tower, or whether it was only a small western tower, as some authorities maintain, it would be equally necessary to remove it before the work of extension could proceed.

I think the foundations prove that it was a central tower, and seeing that a larger tower was in contemplation, a better disposition at the west end would have been to have finished the aisles with well-buttressed, twin towers; as the subsequent failure of the pier arcades to resist the thrust of the arches, which carry the huge weight of the present central tower, was mainly due to lack of abutment at this point.

(1) Some interesting notes on the Wills, Chantries, and Tombs, prepred by Mr. F. A. Wadsworth, will appear in a subsequent issue of the '' Transactions.''