Ever since Edward of York proclaimed himself King at Nottingham, the banner of the White Rose had waved above the castle walls, and both he, and his brother and successor, Richard III., who, in spite of his villainy was ever a patron and lover of art and architecture, had a great liking for the town. It is but natural, therefore, that the cognizance of the Yorkists should be found in a church of which they were presumably very fond.

If we accept the oft quoted statement of an unknown visitor in 1643, who noted "two faire monuments of white marble, one whereof was Salmon's and the other Thurland's," we thus get an approximation to the time occupied in the erection of the "body" of the church; for John Samon the elder, who was four times Mayor of Nottingham, died c. 1395, and Thomas Thurland, a benefactor of the Gild of Holy Trinity, who was nine times Mayor and four times M.P. for Nottingham, died 1473-4.

When speakiug of these transeptal tombs, it should be kept steadfastly in mind, that it is only the canopied recesses that are referred to; for while the effigy, which now lies on the floor beneath the canopy in the south transept, may be, and very probably is, an integral part of the Samon tomb, though in a degraded position, it is quite clear, that neither the Purbeck marble slab, nor the alabaster frontal beneath the canopy in the north transept has any connection with the Thurland tomb. My impression is, that the slab is the "mensa" of the altar-tomb of the founder of the chantry of St. Lawrence, William de Amiens [Amyas], formerly known as William-de-Mekisburgh [Mexborough], a wealthy merchant of the Staple, who flourished in the 14th century, and who acquired extensive property in Nottingham and Gedling. I think it was he who rebuilt Gedling church steeple out of his quarry there.

He died between 1348 and 1369, leaving instructions for his chaplains to provide "at their own cost, for ever, two candles of wax of the weight of six pounds of wax, to burn every Sunday and feast-day, in the church aforesaid, upon my tomb for so long as the mass at the high altar shall be in celebration." [Borough Records, 27th April, 1339-1

The slab now contains matrices only, but if we may judge by the crocketted ogee canopies which enshrine the effigies of the founder and his wife, the woolsack cushions beneath their heads, and the shape of the shields, the missing brass would prove to be one of a large number of similar memorials laid down in England, to commemorate individual members of the merchant class which was then claiming great attention. If the bearings on the shields could be recovered, they would reveal the arms of the founder and his wife; or what is more probable, a dual representation of his merchant-mark. A space for an "inscription in brass begging all who survive to pray for the soul of himself and his wife "is now placed partly in the wall at the back of the tomb, where the inscription never could have been read by anyone; and this fact, together with the instruction about the candles, leads me to think that the tomb stood exposed on three sides, in the south transept, and without any canopy.

The alabaster frontal has been chipped and knocked about, and "bodged" together, in a shocking manner, in order to make it fit into the recess. This is the more to be regretted, seeing that it is a beautiful example of local alabaster work, of which all Nottingham folk might well be proud. It is impossible now to tell where this came from; but in all probability, it originally stood against the west wall of the north transept, with two sides and one end exposed to view.

The sculptured figures of the Holy Trinity, the Annunciation, the Crucifixion, the Angel Gabriel, St. John the Baptist, and an unnamed Martyr, are exquisite. In accordance with prevailing custom, the shields in the quatrefoils would be emblazoned, but the faint traces of painting which they still bear are indistinguishable. As the armorial bearings and all other marks of identification have been effaced, it is only possible to arrive at an approximate date, by comparison with other tombs in the vicinity, whereof the date is actually known. I am thereby led to think, that the alabaster work in question was executed either during the reign of Richard II., or early in the reign of Henry IV. [Compare tomb of Sir Robt. Goushill, who died 1403, at Hoveringham]. In the Borough Records and other documents, the names of a succession of "alablastermen" of Nottingham are found, who carried out important work throughout the years 1368-1529. It would surely be to one of these that the work of St. Mary's is due; and considering the delicacy of the sculpture and the refinement of the details, I am inclined to attribute it to the celebrated Peter Maceon [Peter the Mason], who made "a table of alabaster for the high altar within the free chapel of St. George at Windsor." (c. 1370). This has now been utterly destroyed.

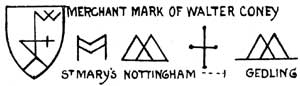

In spite of constant renewals, and the frequent refacing of the masonry, original mason-marks are still visible on the piers; and while these tell us very little about the architecture, it is not without interest to notice that in this church, which owes so much to the liberality of the merchants of the town, the mason-marks are similar in character to the principal merchant-marks of the time.

By the middle of the 19th century, the condition of this church was deplorable; the chancel was divided from the nave by a brick wall, and being thus unused and neglected, had become a harbour for dust and vermin. The nave had been reduced again to four bays in length, by the introduction of a stone screen surmounted by the organ.

In 1842, it was noticed that one of the stones in the south-west pier of the tower-arches had become scored on the surface with fine vertical lines. This proved to be due to crushing weight on the stone; but, although the cracks became perceptibly wider, no notice was taken of it until one Sunday morning, when, during Divine Service, the congregation was startled by a piece of mortar dropping from one of the joints in the tower-arch.

An architect was duly summoned and a careful inspection was made, whereon he ordered the peremptory closing of the church. The tower was at once propped up with timber while excavations were made in order to inspect the foundations. Two causes of weakness were discovered, one below ground and one above, (i) A large portion of the masonry of the south-west pier, some ioft. below the ground, had been cut away to make room for an interment. (2) The fractured stone in the pier above, resulted from the removal of the beam which formerly supported a gallery over the transept. This beam had been ruthlessly drawn out by cutting away all the stonework around it. The cavity thus formed had not been filled in solid, but simply "made good" on the face. Otherwise, the piers and the foundation work below the place of interment were good and sound. The foundation consists of solid close-jointed masonry—the work of an earlier period, which had been carried down to the living rock. It is in this masonry, that several capitals belonging to a still earlier church are embedded. Rough sketches of these, as illustrated in the previous paper, were made at the time by Sir Charles Robinson, but as they were made under great disadvantages, the capitals being fixed upside down, and only visible by the light of a lantern in a deep, dark hole, too much reliance should not be placed upon them.

It was further discovered, that a movement of the south transept wall had previously been arrested, by the introduction, below ground, of a huge mass of brickwork at the south-east angle of the building. This was probably done when the rustic stiles were done away with, and the churchyard was enclosed by the present brick wall and wrought-iron palisade (1807); as the bricks used in the foundation correspond with those used in the wall.

The particulars of this restoration were given to me at first hand, by one who daily witnessed the proceedings throughout the years 1842-8; during which time the foundations were thoroughly examined and strengthened where necessary, a new roof was put upon the nave, and the damaged or decayed stonework throughout was renewed.

But for this timely attention, the tower would have collapsed and involved the whole church in its ruin. While we may be tempted to regret that some of the reparations were not carried out with more regard to the spirit of the past, we must still feel very grateful that such a disaster to the town was averted.

This then is an outline of the story which may be read from the stones of this venerable pile.

Born on a wave of devotion and piety which succeeded the terrible visitation known as the Black Death, steadily rising year by year in spite of trouble abroad and at home—the stirring deeds of Agincourt—the triumph and martyrdom of the Maid of Orleans—the final loss of France—and the carnage and upheaval wrought by the Wars of the Roses—brought to consummation, so far as the external appearance is concerned, ere yet the last of the Plantagenet Kings had set out on the fateful journey from Nottingham to Bosworth Field, St. Mary's dominated the life of the town for nearly a century with a display of wealth and beauty, such as can scarcely be imagined to-day. Then came the Reformation, followed by a period of indifference and neglect, when the pride and glory of the old church was brought low, and its prestige was overshadowed for a time; but the clouds have lifted again and it still stands, not so glorious as of yore perhaps, but quite as much an object of affection and admiration to all loyal citizens. Long may it so continue.

Of the men who built this glorious church, nothing is definitely known. One writer fancied he saw in it so much resemblence to the nave of Winchester, that he boldly proclaimed the famous Bishop, William of Wykeham (1347-1405) to be the designer of St. Mary's also. This claim however will not bear close examination. But when we compare the general design and the details of St. Mary's with the contemporary work at York Minster, we shall find it far more likely that the builders hailed from that city—and Nottingham was at that time in the Diocese of York.

At York, the nave of eight bays (finished c. 1345); the Lady Chapel and Presbytery (c. 1361) containing the great east window—the second largest church-window in the world, occupying nearly the whole of the wall space; the choir arcade of six bays (c. 1380); the central tower (1400-1423); and the western towers (1432-1474) will supply a precedent for all the structural work at Nottingham; while the tomb of Bishop Greenfield at York (1306-1315) is the prototype of the Samon tomb at Nottingham.

The relationship between the work at York and Nottingham is further strengthened, by the fact that the painted windows of the latter contained the arms of prelates, who ruled at York while the work was in progress. The saltire of Archbishop Alexander Neville (1374-1388) a member of one of the most powerful houses in the north and a special favourite with Richard II.; Quarterly gules, a lion rampant or, and chequy or and. azure, all within a bordure engrailed argent for Archbishop Thomas Fitzalan de Arundell (1388-1396); the Royal Arms of Richard II. impaling the arms of his first wife Ann of Bohemia (1382-1394), have been put on record; and we may be sure that many others, including the bend and label of three points of the beloved Archbishop Richard Scroope, appointed by his friend and patron, Richard II. (1398), and beheaded by his successor Henry IV. (1405), while the works were in progress, would also be displayed.

An interesting study is thus presented of a large town church, which reflects in a modest way the glories of a cathedral. And the interest of comparison may be carried still further; for when the members of this Society visited West Bridgford last summer, I drew attention to (1) the prevalence of even numbers employed in the re-building; (2) indications that the work had been executed by village craftsmen who were striving to imitate something they had seen elsewhere. At that time, I was at a loss to suggest the source of inspiration; but after careful comparison, I have since come to the conclusion, that the "solemn, wondrous and manifold sumptuous work," which crowned the summit of St. Mary's hill, within view of the lowly villagers across the Trent, was the object of their emulation.

A further notice of St. Mary's Church, Nottingham, chiefly based upon Wills and Deeds, will be published in the next volume of the Society's Transactions.