ST. LEODEGARIUS, BASFORD.

Basford cemetery and the church of St Leodegarius.

If it were possible to reproduce the face of the country as it appeared “long, long ago,” what an interesting spot this would be. An imagination sufficiently fervid to eliminate the accretions of industrial activity, and to recall the scattered remnants of antiquity in their pristine form, would conjure up a delightful picture.

A journey of a little more than two miles in a N.N.W. direction, brought the traveller in olden days from the Market Place of Nottingham to a village on the banks of a stream which formed the western boundary of the “Great Forest of Nottingham,” or “Shirewod.”

At the time of Domesday Survey (1068) this village contained no fewer than five water-power mills for grinding corn, a cluster of humble dwellings, four old manor-houses, and, older than the manor-houses, “and older than the yew which saw the manor-houses abuilding,” a church which stood on the right bank of the stream hard by an ancient ford. This ford has given a lasting name to the village, but whether its origin is to be found in the “base ford,” i.e., the lower of the two fords by which the stream was crossed and re-crossed; or whether being near the home of Bassa, the ford was colloquially known as “Bassa’s ford,” and this has been glossed over to Basford, will probably remain a moot point; while the Celtic word for the water has been corrupted from Llyn to Leen. The stream still runs its course, but the stepping-stones and the ford have given place to a bridge (1856) and this in turn has been succeeded by a high-level railway bridge; the church still stands beside the stream, but the new bridge has detracted from its dignity and importance, and the new tower and slated roof have given it a modern look. The holy well in the churchyard is now a thing of the past. Faint traces of ancient manor-houses may still be discerned mixed up in a miscellaneous way with railway sidings and all the adjuncts of a flourishing manufacturing district. So that Throsby said of Basford in his day (1795) “the village appears like a new town in consequence of its manufacturing improvements.”

St Leodegarius, Basford—Priest's doorway.

The south side of the church is somewhat obscured from the passing view, but if we betake ourselves thither we shall be in a better position to realize that we are actually in contact with the remote past. The question will then naturally arise “how far back in time do these stones take us”? Before this question can be answered we must strip away, in a metaphorical sense, the accumulations of the passing years and lay bare the original work. If we have sufficient knowledge of mediaeval architecture to do this successfully, we shall see at a glance that some of the work, especially the east end, is at least 700 years old. Domesday book carries us 150 years further back, for therein it is recorded “In Baseford there is a priest,” which suggests, if it does not actually confirm, the existence of a church when the survey was made (1068). But there is evidence of origin earlier still, for the chancel walls contain fragments of worked stone, now hidden from sight, of a very much earlier date. These stones were hewn in Saxon times and appear to have once formed part of a church which was demolished in order to make room for the existing chancel.

We come into touch with tangible things, however, at the beginning of the 13th century, for the pier-arcades of the nave and the chancel walls were undoubtedly the work of that period. The tall, narrow, single-lancets having continuous drip-mouldings and wide internal splays; the priest’s doorway (now only to be seen within the new vestry); the shuttered opening beneath the westernmost window in the south wall, where, in pre-Reformation services, the sacring-bell was wont to be rung; are all in accordance with the“Early English” style of architecture, and point to the first half of the 13th century as the date of erection.

The south porch is a more recent addition, but the entrance doorway which it protects is coeval. The “keel-moulding” of the equilateral arch, and the detached “nook-shafts,” having capitals and bases identical in contour with the mouldings of the pier-arcades within, are eloquent of the excellence of the work of the 13th century builders.

A tablet of porphyry, 31/2in. square, 7/8in. thick, polished on both faces but not on the edges, neatly inserted and fixed with lead in the freestone of the eastern reveal of this doorway at a height of 5ft. from the ground, calls for more than passing notice. For many years all the stonework had been encased in plaster, and the existence of the tablet was only revealed when the plaster was stripped away in 1859.

It is popularly known as the “Kissing Stone,” and there is reason to suppose that it is the “osculatorium” or Pax, at one time used in the celebration of mass.

In the early Christian church the injunction “greet ye one another with a holy kiss” (I. Corinthians xvi., v. 20) was literally observed. So long as the number of communicants was limited, and men sat on one side of the church and women on the other, this could be done with order and decorum. Later on when confusion arose the fraternal greeting gave place to “kissing the chalice.” Symbol once admitted, for greater convenience an instrument known as the Pax was introduced—a tablet of ivory or wood overlaid with precious metals, or even the jewelled cover of an altar book.1 In poorer churches inferior metal or even plain wood was used, hence the term “Pax brede” (or board). In every case it had a handle at the back, and a symbolical device—the rood or Virgin and Child, &c., on the face. After Agnus Dei, this was kissed by the celebrant and afterward offered to the faithful by the clerk or the server.

It is generally assumed that the Pax was introduced into England by Archbishop Walter Gray (c. 1250) i.e., soon after that prelate had re-dedicated this church, and it may be that this stone is one of the earliest instruments used.

The stone is invested with more than ordinary interest when we realize that it has received the kiss of peace from a Pope [Innocent III.]; from the great reforming Archbishop Walter de Gray; from lords and ladies of high degree who have been connected with these manors and estates from time to time; from high ecclesiastics and from parish priests, and from countless residents and visitors throughout the middle ages.

There is no reference to a Pax in the Inventory of church goods made in the reign of Edward VI., probably because marble was useless for the melting-pot, or more probably because it had been fixed in the doorway before that time.

An Injunction published at the deanery of Doncaster, A.D. 1548, ordained that: “the Clarke shall bring down the Paxe, and, standing without the church-door, shall say boldly to the people these words: This is a token of joyful peace, which is betwixt God and men’s conscience. Christ alone is the peace maker, which straitly commands peace between brother and brother. And so long as ye use these ceremonies, so long shall ye use these significations.” 2

On the same side of the doorway the base of a holy water-stoup—another relic of pre-Reformation use—may still be seen. The entrance doorway on the north side is similar in detail, save that the arch is semi-circular, but, with the exception of a portion of the arch-moulding, it is all modern work.

When Stretton visited this church (November 13th, 1815) he found standing at the west end “a low square tower with the remains of a plain Saxon, or early Norman doorway, and leaded roof.”

In 1853, Thomas Bailey published his “Annals of Nottinghamshire,” from the old house opposite the church. Therein he says:—“Of the original erection by Robert de Basford, judging from the style of architecture, the chancel and the tower except the battlements are still remaining in something like their pristine state. The body of the church has undergone considerable alteration, the north and south aisles being of altogether two different styles of architecture; the last mentioned portion being much the most ancient.” p. 41.

On the 3rd of April, 1859, while restorations were in progress, the walls of the old tower collapsed and came down with a crash. The “Nottingham Telegraph,” Saturday, April 9th, 1859, thus records the incident:—“For many years past the venerable parish church at Basford has required constant attention and frequent repair. A few weeks ago the tower was observed to be in a very unsafe condition, and immediate steps were taken to render it more secure. Full consideration was given to all the requirements of the case, and it was determined to adopt a course which it was considered would at once strengthen the tower and add to the beauty of the church. That course was the construction of an arch in the west end of the tower. The tower was supported with strong masses of timber, and every care and precaution taken to render the undertaking effective. The necessary portion of the wall having been removed, it became apparent that the foundation was even worse than had been anticipated, and great fear arose as to the success of the work. However, the energy of those who were employed was increased, and the workmen were engaged day and night during the whole of the latter part of last week, up to 12 o’clock on Saturday night, when they left until Monday. About 8 o’clock on Sunday morning the whole tower fell suddenly to the ground burying the bells beneath the debris. Fortunately, however, although there was “not one stone left upon another,” the bells were uninjured and no person was near; so that the only damage was that sustained by the building itself.”

Nor was this the only disaster, for in 1900 a fire occurred by which much damage was done at the east end, consequently the church now presents a very modern appearance. The walls of the chancel, which are seen to be out of upright, have been plastered and wainscoted, so that internally the ancient “low-side” window and the sedilia are hidden from view. A piscina niche, re-discovered after the fire, is again visible in the south wall near the altar, and there is indication of a credence in the cill of the window on the north side.

The nave arcades of five bays consist of filleted “four-cluster” columns, and equilateral arches in two orders, with plain chamfers. Hood mouldings are employed towards the nave, with sculptured heads on the south side and mitred mouldings on the north side. Originally both sides were alike ; the difference is due to the fact that the chancel arch, the whole of the north arcade, and the west end of the south arcade, have been restored. Only three or four heads on the south side are original and they should be noticed on account of their grotesque expression.

The columns are of slender proportions, 9ft. long, 20in. diameter, and have moulded capitals and bases of characteristic water-holding section. It will be noticed that the springers of the arches overhang the capitals in a clumsy manner, also that the arch stones are of local skerrey while the piers are magnesian limestone. I am therefore disposed to think that the arcades were built in the 12th century, probably in the reign of King Stephen, and that the present piers were substituted in the 13th century for the original piers which would be cylindrical, and of a type having square “abaci” to the capitals, large enough to receive the arches. If this surmise is correct, it indicates that the change was made as part of a scheme for bringing the church “up-to-date” when it was handed over to the Priory of Catesby early in the 13th century. I know of no other theory whereby the overhang above the capitals can be accounted for; and the suggestion is further strengthened by comparison with contemporary work at St. Peter’s, Nottingham, where the mutilation of the “roll-moulding” of the capitals suggests that here also new piers were inserted beneath existing arches under similar circumstances.

|

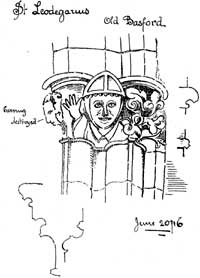

The capital to the respond of the south arcade, although somewhat mutilated, is still the original work. Above the “casement” in the cluster-column facing north-west, set about with stiff-leaf foliage, is the sculptured bust of a female, possibly the prioress of Catesby; facing south-west, a bishop with hand uplifted in blessing. I take the latter to be a representation of St. Leodegarius, Bishop and Martyr, the patron in whose honour the church is dedicated.

St. Leodegarius was bishop of Autun (France). He is known in England as St. Leger. When Autun was besieged (A.D. 678) the bishop defended it as long as possible and then ransomed all the inhabitants at the price of his life. He was cruelly tortured, his eyes were put out, his tongue and lips were slashed, and his body was mutilated in every way. He was eventually put to death after suffering for two years.

How came the saint to be honoured in this parish?3

In order to answer this question it will be necessary to go back to the dim beginning of history. From the earliest times of which we have any record, the manors of Basford (Notts.), Catesby and Leger’s Ashby (Northants.) and Great Ashby (Leicestershire), were in one holding. In all probability the original proprietor was a Frenchman, who either brought the story of Leodegarius with him, or received it through the intercourse which sprang up in the 8th century between English missionaries and the Frankish court.4 His reverence for the saint was so great that not only was the church at his Northamptonshire home dedicated to “SS. Mary and Leodegare,” but the name was actually added to the family seat, which then became Ashby St. Ledgers and so continues.

This devotion was consistently upheld by his successors, for in the 38th year of Henry VI. “a license was granted to Sir William Catesby Kt., kings carver, to found a chantry in the church of St. Leger at Ashby St. Ledgers at the altar of the holy Trinity, or at the altar of our Lady “(Patent Roll, ptI, m3) and this chantry was dedicated “in honour of the Trinity, the salutation of the Virgin Mary, and St. Leger.” Seeing then that Basford once formed a part of the Catesby inheritance, it is not surprising to find the saint was honoured here also.

The connection with the Northamptonshire seat was again exemplified in the 13th century when “the church of Leodegarius at Basford was given by Robert, son of Philip de Basford to the prioress and nuns of Catesby”5—a Benedictine monastery which his father had founded in the reign of Henry II. (c. 1175) or any rate between 1170-1184, and dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary and St. Edmund.

This Robert de Baseford was the grandson of a Saxon named Safred or Sasfrid, an underlord to William Peverel, to whom the manors had been transferred after the Conquest. Sasfrid's son Philip gave “24 acres of demesne land at Baseford” to the Cluniac priory which Peverel had founded at Lenton (1103-1108) and his son Robert, who was variously known as “de Baseford,” “de Catesby,” and “de Esseby” (Ashby) not only confirmed this gift, but he also made a benefaction to the convent at Catesby which was then attracting great wealth and notoriety owing to the miracles which were said to be performed there.

The following transcript is taken from the Torre. M.S.:— “On the 13th of January 1219 the church was by Walter Grey Archbishop of York appropriated to the Prioress and nuns of St. Mary at Catesby, saving to William the priest the whole alterage of the whole parish of Baseford and 21/2 marks out of the oblation of strangers which used to be there offered and which his predecessor possessed in the name of the Vicarage.” “On the 29th August 1227 Walter de Gray Archbishop of York having at the presentation of the Prioress and Nuns at Catesby admitted Robert the chaplen to the vicarage of the church of Baseford thus taxed the Vicarage: that the Vicar have assigned to him the messuage and competent houses built the first time at the charges of those nuns. Also he shall have all the eventions whatsoever arising from the parishioners of Baseford, and that 4s. which the nuns used to receive out of the mill nigh the church, besides the 21/2 marks per annum out of the obligations which accrued to the altar on the feast of St. Leodegar by a view of Liege-men. Moreover he shall have the tythes of the other three mills and the tythe of the meadow of the whole parish.”

(1) Other cases have been known where marble was used, and at All Souls’, Oxford, they had “Paxes of Glass.”

(2) Burnet’s History of the Reformation Records, Book I., No. xxi. Cardwell. Doc. Ann. I., 150.

(3) It is the only dedication in the county, and there were but five dedications at most in England.

(1) Ashby St. Ledgers, Northants.

(2) Basford. Notts.

(3) Wyberton, Lines.

(4) Hunston, Sussex.

(5) Stower Provost, Dorset, now dedicated to St. Michael, but at one time appropriated to the convent of St. Leger at Dreux in Normandy. The spelling of the name varies considerably, but I have followed the original in all quotations.

(4) In the 8th century Saxon England stood well to the front in matters pertaining to religion and art. Her missionaries penetrated as far as the valleys of the Rhine and the Rhone in their efforts to spread civilization and culture.

(5) Two sisters of Edmund Rich, Archbishop of Canterbury, were nuns at Catesby. Margaret, the elder one, was made prioress 1246, died 1257. Alice died 1270. St. Edmund Rich, Archbishop of Canterbury, when dying (1240) “remembering his holy sisters who were nuns of Catesby, left them his cloak of grey colour, made of cloth called camlet, with a cape of lambs wool: and likewise a silver tablet on which was sculptured an image of blessed Mary nursing her Son in her lap, and the Passion of Christ, and the martyrdom of St. Thomas, through which at Catesby, where they are reverently preserved, the Lord works at the present day (c. 1300) miracles worthy of eternal remembrance.”