A good example of a stone-roofed porch may be seen at Linby. Here the vault is supported on bold ribs, which spring from corbels. The angular buttresses terminate at the eaves. They are panelled on the face and decorated with heraldic shields. The apex of the gable also bears a shield which carries the well known arms of the Strelleys, and by these, the date of erection is determined (c. 1488). We have seen that at Bilborough the finials are so large, that no room is left for a niche; at Strelley, there was ample room, but no need for one; here at Linby, the porch is on the north side, and it is a fair presumption that the older south porch (now demolished), would contain the image of St. Michael.

Gedling, and Old Basford once had stone-roofed porches, the former a plain pointed waggon vault, the latter on arch ribs; but in one case the porch has been partly re-built with the old stones, and in the other, a timber roof has been substituted. A 14th century porch at Trowel retains the stone vault, supported by four arch ribs on either side, but modern renewals outside have taken away its ancient characteristics. The south porch to Bunny church is a hybrid specimen with parapets at the side in place of dripping eaves, and a curved pediment in front; for, curiously enough, the stone roofing is made to follow the line of the vault within. The effect (over 6ft. long) remains, and has given rise to numerous and divergent fallacies. The place where slots have been, may frequently be noticed; but they are generally built up with stone.

As time went on, locks and other fastenings were gradually introduced. In the 14th century, handles in the form of a ring, with an iron striking-plate to serve also as a knocker, became general (Sutton-cum-Lound).

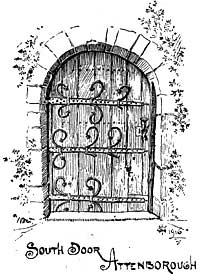

Contrary to the usual arrangement, the south porch at Attenborough has been fitted with an outer door. It is made of oak planking, bound together with three strap hinges of primitive type. It is obvious that it was not made for this position, and the question arises, "How came it to be here?" I am inclined to think that it formerly stood in the Transitional doorway on the north side of the church (now built up), and only came here when the porch was rebuilt in 1860. If this surmise is correct, this is one of the oldest church doors in the county, dating back to the reign of Henry II.1 A door within the south porch at Laneham, and another at Selston, both previously mentioned, are similar in regard to age and style.

The woodwork of the south door at Car-Colston, in date approximates 1270, but the ironwork is not contemporary. On the other hand, at South Collingham the door is dated 1641; but the strap hinges are probably the work of the 13th century. There is a 13th century door with beautiful iron scrolls, in the north-west tower at Thurgarton.

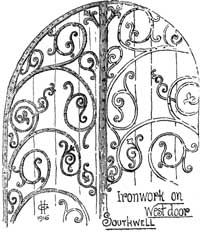

From the very elaborate example on the south door at Worksop, it would appear that iron scrollwork reached its zenith in the 14th century. The south door at Hick-ling is covered with intricate scrollwork, and at Granby, an old door with hinges of flowing design has been reset in the north porch. During the same period, the doorways at Southwell were refitted with new doors. Being exposed to the weather, the west doors were made of plain oak planking, and on the outer face, covered with ornamental iron scrollwork ; the north door is sheltered by a porch, and being thus protected from the weather a different form of ornamentation was adopted, the outer face of the door being covered with moulded ribs, which ascend in flowing lines from cill to soffit, in the form of reticulated tracery. No ironwork is visible from outside, save a strap hinge on the bottom rail, and a closing ring in the centre of the western half of the door. Within the embattled south porch at Langar, there is a door ornamented with tracery panels, temp. Richard II., and this, together with Balderton and the western door at Southwell are the only doors in the county, which have a small wicket framed in the centre of the door.

During the 15th century, several very fine doors were fixed in the vicinity of Newark, and there can be little doubt, but that a local genius, working in the vernacular of the county, produced them all.

The west door at Hawton has already been described (p. 3). At Balderton, the tracery in the head of the door is identical with that at Hawton, save that a statuette of the Virgin and Child, has been introduced at the apex. The words "Jesu mercy Mary help" are carved in relief on a rail at springing level. The central portion of the door is made to open as a wicket. The custom of carving a legend on the door seems to have become general at this time. At Tickhill, a door which perhaps had been the door to the castle chapel bears the the words, "Peace and Grace, Be to this place."

At Barnby-in-the-Willows, the north porch (c. 1480) covers a very fine door. As a matter of fact, this is a combination of two doors; first a door of plain oak planking, cut to fit up to the segmental rear-arch, and into the wide reveals; upon this foundation, an ornamental door is superimposed, made to fit in between the reveals and to follow the line of the pointed arch. The margins are left wide, in order to give strength, but the central portion is framed with slender muntins and crocketted ogival arch, with tracery bars and cusps, after the manner of a three-light Gothic window. If, as has been suggested, the peculiar stone tracery in the chancel windows was also made by the carpenter who framed this door, it is to be regretted that the adage " let the cobbler keep to his calling" was not observed at Barnby, for the door is as good in its way as the windows are bad.

As ornamental woodwork on doors advanced, ironwork fell into disuse, and throughout the 15th century and onwards, panelling and tracery on church doors became general.

The subject has necessarily led me into a wide field of research, but extensive as my task has been, the interest is not exhausted by the statement of bare facts. Tradition and legends cluster around the church porch, and sentiment will not always be denied. The aspirations of the craftsmen who shaped the stones, the prevailing customs and conditions under which they lived and laboured, the joys and the sorrows of some, the comings and goings of whose feet have helped to hollow the hallowed threshold,—these call for expression ; but as these things would carry us away from our purpose, and lead us into the regions of romance, they must await treatment bv other men, in other times.