THE GUILD HALL AND GOAL.1

Town Hall and prison, 1741 (by Thomas Sandby).

Town Hall and prison, 1791 (by R Wigley).

The most imposing building in the area comprised in this paper, was the Guild Hall or Town Hall, which included the Gaol. The main front was on the south side of the Weekday Market Place. The building occupied an extensive triangular space, between what is now Middle Hall and Garner's Hill, and tapered off to the Marsh district.

We are told that the Burgesses of Nottingham "time out of mind and until the time of King John's Charter—and since, had a Gaol in the town for the custody of such as were taken therein as belonging to the town."

One Alan de Bekingham was charged with the death of one Peter de Dynington, in 1285. His case finally came before three of the King's Justices, at Nottingham. Alan then and there stated "that he was a Clerk and member of the Church, and therefore could not nor would not answer. The Justices took the Inquisition. He was declared guilty of murder, and therefore, he was put in the Gaol of Nottingham and there he died. His land was taken into the King's hand, and delivered to the vill of Bekingham to answer before the Justices on the next eyre."2

About 1327, the Sheriff was ordered to repair the Gaol.

In 1330 there was an Inquisition respecting the custody of the Gaol, by the burgesses, in which year the office of gaoler was conferred upon John Doket.

Thomas Copham, in 1355, received the custody of the Gaol and prisoners.

During the next year, 1356, John Brocar succeeded to the gaolership. This man, known as "John the Gaoler," for Richard Gedling, held a messuage by the service of hanging probators and taking the appellants in the counties of Nottingham and Derby. He was, probably, succeeded in his office by a son named John.

Near the close of the fifteenth century it became necessary to enlarge the prison. In 1479, John Pole, of Nottingham gave thirty-five feet of land near the "Guild Hall Gate." The Guild Hall about this period answered many requirements—legal, commercial, and otherwise. It occupied the first floor, and the ground floor was utilised as a armoury, as a barber's shop, and two drink shops. A room over the old hall was, in the seventeenth century, employed as a depot for the "trained bands " of the county. In 1642, the Earl of Newcastle and Sir John Digby endeavoured to seize the stores for the use of the king, but their designs were frustrated by Mr. (afterwards Colonel) Hutchinson, who, as the representative of the people, urged them to abandon the idea of doing so.

Incidentally we learn from the accounts of the Chamberlains, that adjoining or part of the range of buildings was a building known as "Tresour Pious," with a joint gutter. This was repaired in 1485. This was not a residence as might be supposed, but was the treasure house of Nottingham.

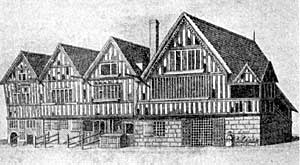

The Guild Hall in 1888.

George Fox, the Quaker, spent "a pretty long time" in the Common Prison at Nottingham during 1649, for disturbing the service in St. Mary's Church, "the great steeple-house," as recorded in his journal of that year in these words:—"As I spoke thus amongst them, the officers came and took me away, and put me into a nasty stinking Prison ; the smell whereof got so into my nose and throat that it very much annoyed me. At night they took me before the Mayor, Aldermen, and Sheriffs of the town. . . . They examined me at large. . . . After some discourse between them and me, they sent me back to Prison again; but some time after, the head Sheriff, whose name was John Reckless, sent for me to his house. ... I lodged at the Sheriffs," and engaged in propagandist work. "Hereupon the Magistrates grew very angry, . . . and committed me to the common Prison. When the assize came on ... I should have been brought before the Judge; the Sheriff's man being somewhat long in fetching me to the Sessions-house, the Judge was risen before I came. At which I understand, the Judge was somewhat offended. ... So I was returned to prison again, and put into the common Gaol."

The Armoury of the town was located at the Guild Hall. When an inventory of the contents was prepared for presentation to the Common Council in 1836, it was found to comprise the following items:—six blunderbusses with spring bayonets; six small pistols; six double-barrel pistols; four small horse pistols; nine horse pistols with spring bayonets; twelve horse pistols without bayonets; eight cutlasses; twelve pistol cases; six blunderbus cases; powder flask; shot flask; shot-ball and cartridges; 11in. lanthorns ; twenty pairs of handcuffs,—verily a formidable Armoury!

On the 23rd January, 1729-1730, the council ordered that the messuage adjoining to the town's "Joal " be let to sheriffs. This was "intended to be an habitation for the 'Goaler' of the town, who is to have the use of the two rooms adjoyning to the Council Room and the Garrett over the same, and Sellar under 'Goal' during pleasure, and if the said 'Goaler' shall lay out any money in or about the said rooms and garret, he shall have an allowance made him for the same, if any future Sheriffes shall not think fit to continue the said 'Goaler' in his place as shall be thought reasonable by the Hall."

On 1st August, 1729, there was "aide to Thomas Simpson for mending the 'Jalers Scale' and 1d. in pipes, 7d."3

(1) Much has been written about this public building. To the pages of "Notts. & Derbyshire Notes and Queries, for 1895," I contributed three chapters, which, with the illustrations, were issued in a very limited edition under the title of "The Old Guild Hall and Prison of Nottingham." This material in a condensed form was reproduced thirteen years later in my "Chapters of Nottinghamshire History." As this data is thus readily accessible, and in consideration of space, it is omitted from this paper, but some fresh information is printed here, so as to make the story of the Guild Hall still more complete.

(2) As Mr. H. Hampton Copnall writes (Notts. County Records):— "Privilege of Clergy consisted originally in the right claimed by the Clergy to be free of jurisdiction of the Lay Courts and to be subject to the Ecclesiastical Courts," but in this case the plea was not entertained.

(3) The Corporation afforded Dr. Charles Deering facilities for perusing various documents in their possession, under the supervision of committees specially appointed for this oversight. During 1740-1, the Common Council passed resolutions to this end. Thus, on 2nd April, 1740, a committee of two Aldermen, both Coroners, and two Councillors, were appointed "to attend the [Guild] Hall 'whilest' Doctor Deering inspects some writings and records of this Corporation, in the Repository." On the 27th of the following February, a committee of "five at least" were instructed "to search among the Records, and see into such matters as Doctor Deering desires to have inspection of, and to ' incert' into his History." A year later, on 2nd February, 1741-2, "papers were ordered for the perusal of Doctor Deering"; and ten days later "some grants and papers were delivered to Mr. Coroner Hornbuckle, with a note thereof, in order to lend or show the same to Doctor Deering." Biographical notices of Deering, who died in 1749 (two years before his great work was published), will be found in local historical works, by Bailey and others. The salient facts, however, in the life of Dr. Charles Deering were these:—He was supposed to be of German origin, but graduated M.D. at Leyden, Holland. Arriving in London he was appointed Secretary to the British Ambassy at the Court of Russia. On returning to London he married there, but his wife shortly afterwards died there. He subsequently came to Nottingham, and practised medicine with some degree of success. "He became," Bailey says, "reserved, morose, and capricious," which "alienated from him his early friends and patrons, and hurried him rapidly into a condition approaching the most extreme poverty." He projected his "Not-tinghamia Vetus et Nova," and submitted his scheme to Mr. John Plumtre. He approved of it; and furnished him with material for the work. His monetary condition, chagrin, and infirmity of temper ruined his health, and he died on 25th February, 1749, in lodgings on the south side of St. Peter's Square. He was buried in an unmarked grave in St. Peter's church-yard. Bailey says that the Corporation provided for his interment and also that Ayscough (Nottingham's earliest printer), and Mr. Willington, a druggist, defrayed the cost of the funeral. These two tradesmen became possessed of his manuscripts, administered his estate, and published the history in 1751. Deering also issued a "Catalogus Stirpium," and a treatise on small-pox issued in 1737.