The study of village churches in groups by the inductive method often yields good results. The analogy between the chancels at Barton, Wilford, and Wollaton, is too striking to admit of any doubt as to their emanation from one and the same source, and we are thus enabled to arrive at a full interpretation of the one by comparison with the others.

For instance, I commenced my description of Barton Church with a reference to an image of the patron saint, although no image has been seen there since the Reformation. I had no hesitation in doing so, because it is well-known that parishioners did usually set up an image of their patron saint in the church. But if no other source of information was available, I think a study of these three chancels would lead to the same conclusion, for if we turn to Wilford, we find there, on the eastern wall, two tabernacle niches, defaced almost beyond recognition, while yet retaining fragments of detail, which, when well looked into, arc found to be in correspondence and therefore coeval with the chancel. It would be safe to postulate that these were made to contain images of S.S. Wilfrid and Katherine, the two saints honoured in this church.

At Wollaton we get more tangible evidence still. In 1469, i.e. very shortly after the chancel was built, Richard Willoughby in his will, desired to be buried "at the end of the high altar, on the north, before the image of St. Leonard," against the new monument he himself had lately built—presumably on the death of his wife in 1467. It is quite clear that a portion of the original north wall, eastward of the Willoughby Chapel, was cut away, and one of the windows was partially blocked up in order to admit this tomb. The beginning of an inscription "Orate pro aia Rici Wyllughby," excellently cut in black-letter, may still be seen on the projecting outer face of the tomb, but it is now in a perishing condition. As Richard Willoughby died 7th October, 1471, there can be no doubt that an image of St. Leonard, the patron saint, filled the niche on the north side of the high altar at Wollaton, at that time.

The fenestration of the three chancels is practically alike. All have angular buttresses at the east end; the chancel doorways are identical almost to a line, save that at Wollaton it is obvious that one moulding and one fillet were destroyed when the doorway was brought forward and reset in 1885-6. It is a fair assumption from such portions as remain, that even the gable-crosses were all similar in design; the tracery of the east windows might well have been all worked from one template, as already described, while all the windows clearly exhibit a gradual development one from the other.

At Barton, and Wollaton, a wide simple "wave-moulding" sufficed for the window jambs, &c., but at Wilford a complex moulding consisting of a "wave," a wide "casement" and two deep hollows was used. Again, at Barton there is an independent two-light window, with low cill, at the west end of the south side. At Wilford, a low-silled window is contrived in combination with the westernmost chancel window and only separated from it by an embattled transom. At Wollaton, where there was no projecting south aisle to obscure the light, no low side window was provided—an indication to my mind that this class of window must not be confounded with shuttered openings, as it had no ritual significance, but was simply intended to give light where it was specially needed. The internal arrangements have been altered again and again, but there can be little doubt that the sedilia and piscina at Barton are the original design. At Wollaton the insertion of the tomb of Henry Willoughby, (obit. 1528,) has caused two-thirds of the sedilia to be cut away, but it is clear, from the remaining portion, that it was originally in correspondence. The piscina niche now worked continuously in the same design, is a modern innovation. At Wilford also the piscina nichc is modern, but here it is worked after the original manner, minus the small recesses for crewets, which arc now only to be seen in the fenestella at Barton.

It is noticeable that, apart from the sedilia, there is an absence of carving in all three churches; the semi-octagonal pendant, already described, being used where-ever possible.

Another characteristic feature is the newel staircase enclosed within a semi-circular turret. It occurs with scarcely any variation in the steeple at Barton, and the rood-stairs at Wilford; it is also seen at Holme Pierre-pont.

In order of building I think Wollaton was the first, as Wilford was the last of the trio. At Wollaton the "body" of an older church was adapted to a new chancel at the east end, and a new steeple at the west end; at Barton the chancel was but the beginning of an entirely new church; at Wilford the chancel was an addition to an existing nave and aisle. If we may judge by the arrow-sharpening, and other external markings on the eastern side of the internal wall between nave and chancel, the earlier chancel most probably had lain derelict for some time.

It is obvious that the three chancels were not built by village masons, but rather by trained experts, skilled in all the intricacies of mason-craft. The work is well executed, and it is not the fault of the craftsman that the sandstone has not always successfully withstood exposure to the weather. There was no parsimony of labour. For instance, a moulded string course 3m. deep, projecting 3m. from the wall face, is worked on a course of ashlar 12in. deep; all the semi-octagon pendants are either worked out of the solid, on large blocks of stone, or they are formed on separate stones and neatly notched into the block. The arch-stones of the doorways have the two orders of mouldings and the hood-moulding, not self-existent, but all worked on one block of stone; while the upper and lower jamb-stones have the attached nook-shafts with their respective caps and bases worked on; the head of each light in the side windows is pierced out of a single slab of stone, and this seems to have been their traditional manner of working: for the main portion of the tracery of the east window is also out of one large slab of stone. Horizontal bands and patches of iron oxide stain bespatter the face of the ashlar masonry, but wherever such a patch would have caused disfigurement to a moulding it was carefully cut out and replaced with a square of clean stone.

The true archaeologist is not content to praise the skill of an unknown designer, until he has put forth every effort to ascertain the source of inspiration.

Bearing in mind the care and attention bestowed upon the masonry, and especially upon the stone furniture of the chancel, my admiration emboldens me to suggest that this work may be ascribed to a well-known guild of masons, who emanated from York, and built the choir at Southwell in the second quarter of the 13th century; whose handiwork may be clearly and continuously traced, for a century or more, in the churches of this district, when it culminated in a series of glorious chancels erected during the second quarter of the 14th century, of which Hawton is perhaps the finest and the best known.1 Then came the "Black death," and the guild is supposed to have been decimated and dispersed. But I think there must have been a brief revival, as Barton and its prototype bear witness.

The fact that this guild is known to have been employed by the princely Roger of Norbury, Bishop of Lichfield, 1342-7—i.e. before the pestilence—to build a chancel at Sandiacre, just over the county boundary, where an outcrop of sandstone was used, would reasonably account for the employment of the same bed of stone at Barton, especially, as we have already seen that transport would be simple and easy.

The revival appears to have been brief in duration and limited in capacity, for, as already noticed, the glorious carving and sculpture of the earlier school was but sparingly attempted by the later school. Before the pestilence the bold portrayal of king and queen, together with knights and ladies, in the characteristic head-dress of the period, was profuse on stops to hood-moulding, pinnacles and at every available point. After the pestilence it was only on pinnacles which rise above the cornice, the sedilia, and the image brackets, that any carving was used at all, and that only of a feeble type. Nevertheless, their work is more logical and evolutional than we should expect to find at that period, and always it bears the stamp of refinement and distinction.

I think I can dctect their handiwork in additions to several churches in the immediate neighbourhood. For instance, the clerestory at Clifton appears to have been added by them while they were still working in coal-measures sandstone, probably during the interval which elapsed between the building of the chancel at Barton-in-Fabis and the erection of the steeple there, for the tracery in the square headed windows of the clerestory at Clifton is clearly the prototype of the tracery in the steeple at Barton-in-Fabis. The west front at Clifton has recently been stripped of a thick growth of ivy, which has disclosed the fact that the original walling, built of very inferior, thin-coursed rubble, of local stone, and smeared over with plaster, is held up by two heavy rectangular buttresses which counteract the thrust of the arches in the nave arcades. These buttresses, like the clerestories, are built in coal-measures sandstone, and appear to have been added by the builders of the clerestories who also put the coping on the western gable, and the very fine gable cross with crucifix, which, owing to the removal of ivy, is now revealed in all its beauty. When we remember that only one other ancient church in this county (i.e. chancel at Woodborough) can shew a crucifix on the gable cross, and when we know that this was executed by the band of masons under notice, about half a century before Clifton clerestory was built, the point gives added interest to our enquiry and consequently leads us back to our starting point.

On the opposite bank of the river they built a very fine steeple at Attenborough, and there again their regard for the preservation of more ancient work is manifest, for, while, for obvious reasons, the steeple is set not quite clear of the Transitional nave arcades, so that a portion of the fourth and westernmost arch on either side is crippled and embedded in the eastern wall of the tower, the south arcade which had begun to fall considerably outwards, was stayed from further mishap by the expedient of building a rectangular buttress outside the wall, and connecting it with the arcade by means of a flying buttress across the aisle. There are two of these half-arches on the south side. When viewed only from within they are a puzzling feature as their purpose is obscure ; but to the student of construction it is obvious.

It needs but a cursory comparison to show that the builder of the later work at Barton-in-Fabis was also the builder who added the steeple, and the buttresses to the arcade at Attenborough, for the workmanship is akin and the same bed of mill-stone grit is used in both cases.

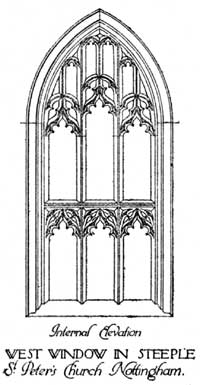

Although the mother Church of St. Mary, at Nottingham, was undergoing reconstruction in the 15th century, I can find no trace of the handiwork of this particular guild therein, (except it be in the very earliest work started in the reign of Richard II.) which looks as though their influence was then on the wane. They appear to have been at work in the town early in the century however, for, if we compare the steeple at St. Peter's, Nottingham, with the steeple at Attenborough, or with the general work at Barton-in-Fabis, the similarity is found to be too striking to admit of any doubt that all emanated from one scource. The ashlar masonry, the proportion and detail of the tower arch,2 and the tracery of the tower window at St. Peter's, Nottingham, when compared with the work at Barton-in-Fabis, are especially striking in their similarity.

Architectural design and draughtsmanship, as we know it, was unknown in the middle ages; the building scheme was brought to completion by the master mason working with his men: so that the name of the designer seldom comes down to us. It is not without interest to note that two names in graffito on the stones of Barton may possibly relate to the builders. They are both of contemporary black-letter type. One is on the soffit of the priests doorway3 Siwart Tayleur the other is on the west side of the base-moulding of the eastern pier in the arcade Hic fuit Henricus Chilom. The name of "Ric Killom" (i.e. Kelham) appears in Torre's list of rectors, 1408-1415 — Torre may have confounded "Ric" with "Henricus," or it may be that the latter was a craftsman and a blood relation of the former who was rector.

"In no art is there closer connection between our delight in the work and our admiration of the workman's mind, than in architecture, and yet we rarely ask for a builder's name. The patron at whose cost, the monk through whose dreaming the foundation was laid, we remember occasionally; never the man who verily did the work." (Stones of Venice, vol. I., The Foundations, page. 38.—John Ruskin).

The church, as already stated, is dedicated to St. George, but unfortunately the patronal festival has long been in abeyance. The axis of the church shews a deviation of 10 degrees to westward of due north, and 5 degrees eastward of M.N., the variation in the compass being now 15 degrees to W.

The Parish Registers go back to 1558, i.e. within twenty years of their institution.

An item of interest in the parish register reads as follows :—

"Memorandum. It began to rain on Fryday the second Day of July, 1736, about six in the Evening, and continued raining incessantly till Monday following, about eight or nine in the morning, when the Trent swell'd to that Degree, that about five a clock the same evening The water was twelve or thirteen inches deep all over the Church Floor,4 which is the more remarkable, because the water was never Known to rise up to the walls of the Church, in the memory of the oldest person now alive.

July ye. 1736, Jos : Milner, Rector."

Sixty years later, a more alarming flood occurred, known all along the Trent Valley as the great Candlemas flood. On December 24th, 1794, a frost commenced and continued with heavy falls of snow until February 7th, 1795, when a thaw suddenly set in causing disastrous floods in the Trent Valley (vide. Blackner, p. 15. Throsby, vol. a, p. 75; also mark 0n churchyard wall at North Collingham). On a brick pier opposite the Smithy at Barton, a slate panel has been inserted to indicate the height reached by the flood on Wednesday, February 10th, 1795. If this mark can be relied upon, the flood rose 5ft. 6in. above the surface of the road. The base stone of a buttress, exactly opposite to this panel, carries the arms of the Sacheverells fixed upside down.

Practically nothing remains of the old manor-house of the Sacheverells save the stone carving, before mentioned, an octagonal brick dovecote and fragments of brick walling. The Sacheverells became lords of the manor, c. 1522, by the marriage of Sir Richard Sacheverell of Morley, co. Derby, with Elizabeth, daughter and sole heir of Henry Grey, "base son" of the last Lord Henry Grey of Codnor, by whose family the manor had been held in succession since the 6th year of king Edward III. (c. 1333). Mural monuments to Henry Grey and several of his descendants are in the church. An alabaster tomb, carrying effigies of William Sacheverell, Esq., who died 8th March, 1616, and Tabitha his wife, daughter and sole heir of James Spencer, remains on the north side of the altar. According to the will of William Sacheverell, dated February 12th, 1616, he desired "his body to be buried in the church at Barton, with a tomb or memorial for him like the tomb of Ralph Sacheverell his late deceased father, or else a tomb to be over his body like the tomb of William Sacheverell, his grandfather, as it is erected in the church of Stainton near Swarkestone Bridge." Ralph Sacheverell was the nephew of Sir Richard Sacheverell, the first owner of the manor, whose only son Henry had died without issue. The estate was held by two Ralphs, father and son in succession, then by William, whose effigy has been noticed, his son Henry, and grandson Robert, and finally passed to the Cliftons by purchase after the marriage of a daughter of Robert Sacheverell to George Clifton, c. 1715.

(1) Hawton: c. 1320. Sibtlhorpe: c. 1324. Car-Colston: before 1349. Woodborough, Arnold and Epperstone, in Nottinghamshire; Heckington: before 1345, in Lincolnshire; Sandiacre: 1342-7 in Derbyshire.

(2) Barton: (chancel arch) 9ft. 4in. wide, 17ft. 6in. to springing line; St. Peter's: (tower arch) 11ft, wide, 26ft. to springing line, 34ft. to apex.

(3) See previous Vol. XXI.

(4) The Church floor was lowered, c. 1887.