Summer Excursion.

THE necessary restrictions, imposed by war-time, have made it impossible for the Society to arrange any excursions during 1918, but a short half-day's visit was made on Tuesday, June 25th, to the church and village of Edwalton. About fifty members availed themselves of the opportunity, and by the kind invitation of Jesse Hind, Esq., J.P., were entertained at tea in the pleasant garden of his house in the village. The party then visited the small, but interesting, church of the Holy Rood where the following paper was read.

Edwalton church.

By Mr Harry Gill

Edwalton church.

In the far off days before the coming of the Normans, a Saxon settler named Eadweald, reclaimed a parcel of waste, boggy land, lying about a league away from the "burgh" of Nottingham, on the south side of the river, and established thereon an enclosed farmstead. Since that time many changes have taken place but the village which gradually grew around Eadweald's "tun" still bears his name in the form of Edwalton.

There appears to have been no church at Edwalton for at least a century after the Conquest. Tollerton Church, only a mile away in a direct line, was separated by an impassable bog. The nearest available church was Flawforth,1 a mile and a half away on the high ground to the southward.

The early annals of Edwalton are fragmentary and baffling, but we are on safe ground in assigning the erection of a church here to the latter part of the 12th century, for when Beauchief Abbey was founded by Fitz Ranulph, the lord of Edwalton, c. 1175, Edwalton Church was included in the endowment.

Its genesis, therefore, goes back to the early days of the Angevins, when Saxon and Norman, forgetting past feuds, were content to dwell in amity around the cradles of a new race of Englishmen; when, for the first time since the Conquest, the Church was ruled by an Archbishop who was born in our own land; and when church building as an act of piety was fast becoming an absorbing passion.

We know that Fitz Ranulph succeeded his father Ranulph Fitz Ingleram, a.d. 1166, and that he filled the office of Sheriff in the counties of Nottingham and Derby. The inference is that as he went to and fro in the land, he caught the spirit of emulation and set out to build a church on this, the smallest of his numerous estates. As the status of the parish priest was not yet fully established, it seems likely that in accordance with custom, once common in England, and then still prevailing, the lord of the manor appointed one of his chaplains to act for him in the spiritual oversight of his tenants. This brought hitn into sharp conflict with ecclesiastical authority, and incidentally it gives us the earliest direct mention of the existence of the church. Archbishop Grey's register, under date 6th October, 1228, contains an account of a dispute which arose between the rector of Flawforth and the lord of Edwalton and his men, "touching the Chappel of Edwalton." The case was heard before the Chancellor and the Dean of Oxford, the Pope's delegates, and confirmed by the pontifical authority of Walter Grey, Archbishop, "That the Rector of the Church of Fanflour for the time being, for four days in a week shall celebrate divine service in the said Chappel of Edwalton, and that the Lord and Men of Edwalton, for the support of that burden, shall assign two oxgangs of land and one toft in perpetual almes."

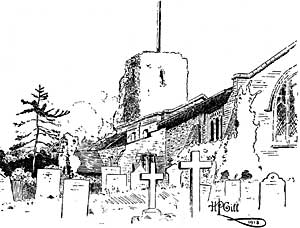

This early building may lack architectural interest, yet like many another humble fane it charms us by its power to recall the past, and to set the imagination dreaming. When we realize that the nave wherein we are assembled, is actually a portion of the original church, an appeal is made to our veneration and respect, for we may rest assured that for seven centuries and more, a long unbroken line of Fitz Ranulphs, and their successors the Chaworths, including Lord Byron's beautiful "Mary," have paid their devotions within these hallowed walls.

Notwithstanding the fact that all the workmanship is plain and simple, bearing the impress of the village artificer rather than the skilled craftsman, it is still possible to trace its evolution, and to separate the work of succeeding generations.

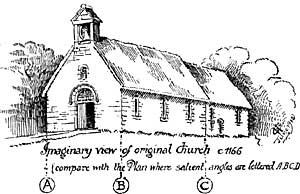

If we ignore for the moment the aisle and the tower, which were subsequent additions, and substitute a small plain chancel for its modern successor, we can picture the church as it originally stood:—a simple parallelogram with thick, unbuttressed, rubble walls, built of stone obtained in proximity to the site; for the peat swamp which lay nearly all round the "tun" and formed its natural defences, made it difficult to bring building material from elsewhere; the only entrance to the church was a doorway at the west end; a small bell-cote on the gable above it; the south wall of the nave pierced by narrow slits for the admission of light; the north wall plain and solid throughout its entire length, but having a wide external projection near its eastern end, which piques our curiosity for it may yet hold a secret. This projection is built with the same kind of stone, and in exactly the same manner as the original north wall; but a thick mantling of ivy outside and a coat of plaster and colourwash inside, baffle all attempts at research and we are fain to be content with a surmise. Is it merely a buttress added to counteract the thrust of a new roof which was put on when the aisle was built, or was it, as its size and position seems to indicate, the tomb of an early benefactor?—not Fitz Ranulph the Founder, because we know that both he and his son were buried at Beauchief.

The bowl of the font belonging to the early church is still in use. It is unusual in shape; being cut out of an oblong block (30in. by 24in.) of magnesian limestone. A remnant of the iron staples for the cover may still be seen in the rim.

When this church was in building it was a custom, and in 1236 it became an order, for every font to have a cover. The consecrated water was left in the font and changed only at stated intervals. In order to prevent it from being stolen and used in the practice of witch-craft, then very prevalent, it was found necessary to provide every font with an oak cover secured by an iron bar with staples and padlock fastenings.

The present incongruous font cover is quite modern. It was made up from some oak panelling, by a native of the village. The finial is a "poppyhead" from a 14th century bench end, which was found in the roadway near the village some years ago. As it is more ornate than anything connected with the old church it seems unlikely that it ever had a place here before. The original position of this font was on the west side of the pier to the right-hand as you enter by the south doorway, and there it stood for ages. At a later time it was set up for a brief space in the tower on a brick base encased in wood. The pillars which now support the bowl, and the lead lining, date from 1894 when the font was fixed in its present position.

Thus the church stood when it left the hand of the builders. Its salient angles may yet be determined by the light-coloured grey waterstone sandstone, which, although inferior as a building material, has nevertheless withstood exposure for centuries.

Right on the threshold of the history of the church we are confronted with a tradition that it is one of a number of churches built in expiation of the murder of Thomas-a-Becket; and that its founder was actually one of the perpetrators of the crime.

It is a thankless task to discredit a long cherished tradition, but in justice to the founder, one or two facts should be stated.

Our own historian, Dr. Thoroton, in his history of Notts, (p. 64), says:—"Robert (son of or) Fitz Ranulph, who was High Sheriff of these Counties, 12 Henry II., and so much a zealous servant of the King, that he is reported (how truely I know not) to be one of those who committed that foul Murder on Thomas Beckett the Archbishop of Canterbury, for which (besides two others) he built the Abbey of Beauchief in Darbyshire, to which he gave this church (i.e. Edwalton) together with the churches of Norton and Alfreton and Wymondeswold, those Lordships continued long with his Posterity, and this doth still."

Camden is equally guarded in his language, when he says:—"who is said to be one of those knights who assassinated Thomas Beckett."

Glover in his history of Derbyshire says that the Praemonstratensian Abbey "de Bello Capita" (Beauchief), two miles from Norton, was founded 1172-1176, by Robert Fitz Ranulph, Lord of Alfreton, Norton and Marnham, "who according to Dugdale, Tanner, and other writers, was one of the four knights who assassinated Thomas-a-Becket."

The names of the four knights which have come down to us in connection with the Canterbury tragedy of 1170, are: Reginal Fitz-Urse, who is reported to have said "where is the traitor Thomas Becket," William de Tracey, Hugh de Morevilla, and Richard Brito; an unlearned monk Ranulph-de-Broc, is credited with having scattered the martyr's brains on the ground with his sword, and afterwards given shelter to the assassins at Saltwood, in Kent. I am therefore led to suggest that the similitude between the names of the knight, Fitz Urse, the Baron Fitz Ranulph, and the monk Ranulph de Broc, has caused confusion and may have given rise to the tradition.

As the chief perpetrators were deprived of their knighthood and estates, and banished from the realm, the further attempt which has been made to identify Fitz Ranulph with Richard Brito cannot succeed because Fitz Ranulph was a Baron, who not only retained his titles and estates (as Thoroton is careful to tell us), but as we have already seen he held the high office of Sheriff both before and after the murder; an office held by his father before him and by his brother after him, nearly all through the long reign of Henry II.

It is true that Robert Fitz Ranulph built and endowed an abbey, near to his ancestral home at Norton, to the honour of the Blessed Virgin and the recently canonized [1173] St. Thomas the Martyr, wherein was an altar dedicated in honour of Holy Rood, and a carving in alabaster representing the assassination of Thomas-a-Becket, which is supposed to have been the original altar piece, but there is nothing to suggest that it was done by way of penance and expiation.

Edwalton Church was confirmed to the Abbey of Beauchief, by charter of Edward II., 20th February, 1316. There is no suggestion in the charter that the gift was an expiatory one. The phrasing is in the usual form, "for the health of the soul of King Henry II., and the souls of his children, and for the health of his own soul, and the souls of all his relations." That it was no mean gift, is shewn by the Taxation Roll of 1291, wherein Edwalton Church brought to the abbey twelve marks yearly.

The tradition has gained support from an erroneous impression, which is current, that all churches dedicated to Holy Rood have some connection with the martyrdom. Only three churches in this county, viz:—Edwalton, Epperstone, and Ossington, are thus dedicated, but throughout England there are twenty-three churches dedicated to Holy Rood, and eighty-three to Holy Cross, i.e. 106 in all.

Edwalton Church is now known as the Church of Holy Rood, but there is some uncertainty as to its original dedication. Canon Raine, relying upon pre-Reformation wills in the York Registry, says it should be St. Lawrence, while Ecton's List (1763) says, Holy Rood.

In mediaeval times it was no unusual thing for a church to receive a compound dedication, and this church, although the smallest edifice in the hundred of Rushcliffe, and at first only a chapel to Flawforth, may yet have been dedicated to St. Lawrence and Holy Rood, but as not infrequently happened with dual dedications, one of the names has been allowed to lapse.

(1) Flawforth is now only a name. Its church went out of use in 1718, and was completely demolished 1773-4. The only traces remaining are a neglected graveyard surrounded by ragged elm trees, a few scattered gravestones (one is used as a pantry shelf in a cottage in this village), fragments of worked stone in walls and bridges, and three beautiful alabaster figures: which are now in the Castle Museum. The figures were found beneath the debris of the chancel in 1779. They are probably 14th century work, and represent St. Peter, patron saint of the church, the Virgin and Child, and an unknown Bishop.