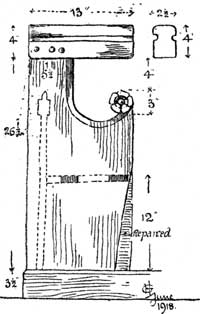

On entering by the south doorway, a poor-box1 stood against the wall on the right-hand side—a short pillar of oak 6in. square, hollowed at the top to form a box 3m. square, 2in. deep, covered with a hinged lid, having padlock fastenings; the font stood near the door, against a pier of the arcade, as already described; the altar, a plain Elizabethan Communion table, simply draped, stood in the centre of the east end of the nave; on the side of the aisle stood a modified "three decker" arrangement having an enclosed reading desk with clerk's seat in front, and a raised pulpit leading out of the desk with a sounding board above it; on the opposite side was the manor-pew with a window pierced in the north wall to light it; on the wall at either side of the altar the Belief and the Lord's Prayer were displayed in black frames; the Commandments were at the west end on either side of the tower arch.2 The nave was crowded with close pews framed in deal; on the north side, after the manor-pew came four or five pews assigned to the tenant farmers, and beyond them the "singing seats"; on the south side, westward of the passage, were three oak benches3 which had probably formed a part of the furniture of the church when seats for parishioners were first introduced in the 14th century; the space between the old benches and the western wall was occupied by two graduated deal-framed pews for the choirmen who played on musical instruments.4 Henry-Hancock [1793-1835] is still spoken of as the clerk who played the hautboy and led the orchestral accompaniment; his successor William Taylor [1835 - 1882] was the last survivor of the parochial church band; he retained the lower of the two seats as his family pew, until his death in 1882. Shortly afterwards an organ was set up where the raised pews had stood, and the close pews in the nave were all cleared out and replaced with chairs; the three old oak benches remained in situ until 1894.

The external appearance, viewed from the west, was much the same as it is now. It was at the east end where incongruity was manifest. A flat expanse of brick wall, with a large round-headed window in the centre, and a smaller square-headed window of domestic type on either side of it; a chimney corbelled out near the top; the whole interspersed with mural tablets relating to interments made on the site of the demolished chancel.

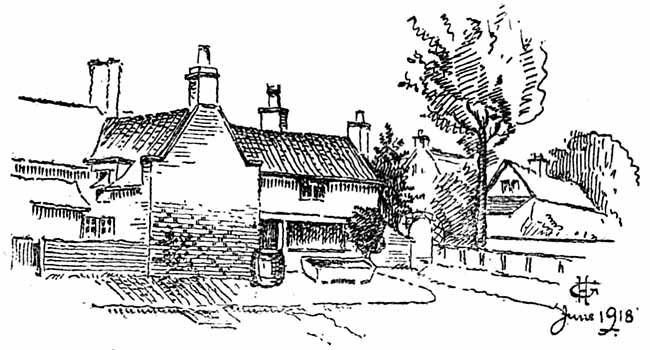

A "stud and mud" thatched cottage, formerly known as "the Parsonage" but at that time occupied by the clerk, stood within the churchyard by the gate. The church Terrier [25th June, 1770] described it as "a small cottage built with clay and thatch, containing two small rooms." Twenty-five years later Throsby wrote:— "The parsonage which stands at the edge of the churchyard, is one of the most wretched habitations I ever beheld"; he then proceeded to contrast it with a "handsome barn" on the opposite side of the way. Nevertheless the "parsonage" survived for another hundred years, when it was demolished, under a Faculty dated December 16th, 1874.

[1894.] A new chancel was built and the nave was modernized, when a memorial window to Mr. James Bell, a foundation member of the Thoroton Society, and a staunch supporter of this church for thirty years, was placed on the north side of the chancel, and triple sedilia bearing the following inscription on the south side:—

IN MEMORIAM.

GULIELMI. JOANNIS. CRUFT.

SERVI. DEI. FIDELIS

PAROCHIAE DE EDWALTON

PER XVII ANNOS

MDCCCLXXIV : MDCCCXCII

VICARII

HOC SAXUM DEDICATUM

EST

EP. AD. GAL V. XXII.

A silver cup and paten, still in occasional use, is of more than ordinary interest. The cup has been soldered5 in more than one place, and is worn thin and smooth until the marks are illegible. It stands 6in. high; the bowl is 3in. deep and 3½in. diameter at the mouth; the foot is a plain circle, 21/8in. diameter, of the usual flat dome shape; the stem ¾in. diameter is bossed in the middle; the bowl is almost flat where it joins the stem, rising with straight sides which slope outwards and curve towards the lip. The paten cover is a flat dome made to fit over the cup, with a plain flat button 1in. diameter which serves as both handle and foot. Cup and cover are uninscribed and plain, save that a moulding at the base of the bowl, and the flat outer rim of the foot are relieved with a band of engraved ornament.

I have already noticed that a silver chalice was included in the Inventory of church goods handed over to the Commissioners on the 4th September, 1552. On May 8th in the following year they returned to Crystofer Nyghtingal, parson of Edwalton "on chales of sylver wyth a paten for the admynstracyon off the houly communion." It is not unreasonable to suppose that they returned the same piece of plate which they had taken away eight months before, and this in turn was probably the mediaeval chalice which had been remodelled in compliance with the Royal Proclamation, prefixed to the Order of the Communion in the year 1547, when the cup was restored to the laity as instructed in the first English Prayer Book of 1549.

Edwalton Church thus ranks with half a dozen London churches, and a dozen or more in the provinces which boast of altar plate contemporary with the boy King Edward VI., and therefore holds the proud distinction of possessing the oldest post-Reformation chalice in this county.

The registers date back to A.D. 1545. The earlier parchment sheets are illegible in parts owing to ravages committed by damp, and by the church mice of former generations. The earliest legible dates are Burials 1562. Baptisms 1567. Marriages 1600.

The church-warden's accounts contain much interesting information, and supply the background for a picture of church life during the 18th century.

The earliest headstone in the graveyard bears a simple inscription "Mary Hallam dyed May 16, 1686"; by its side is another to "John Hallam dyed Sept. 5, 1688." If these stones ever contained any other words they have been swallowed up in the boggy nature of the land.6 Near to the south porch there is a slate headstone, date 1741, with a curious inscription which has been quoted again and again. Stretton says it is "the only matter of curiosity" in connection with the village. As a matter of fact the doggrel rhyme: "She drank good ale, good punch and wine, and lived to the age of ninety-nine," is neither original nor unique.

At the rear of the cottage nearest the church, there is a large stone trough which may possibly have been a sarcophagus in the old chancel, when it fell into ruin in the 17th century. There are several similar troughs in the neighbourhood, and it is a moot point whether they are sarcophagi "put to prophane use" or not. From their size and shape I think the suggestion is likely.

The manor-house stood just across the way from the churchyard gate. The more recent portion of it was occupied as a dwelling until c. 1874, when it went to decay; the adjoining land to the north, where the foundation lines of extensive buildings may be traced, is still known as "the hall close." The outbuildings at the rear of the village post-office and the cottage to the east of it are the only surviving remnants; the brickwork and oak timbering are mellowed with age and there is a very large stone trough and a bake oven of the "chaffer" type. In the boundary wall, to the west of the post-office, a remnant of brickwork which formed part of the front of "the handsome barn," before referred to, may yet be seen; the stone walls of the manorial dovecote are incorporated in the house inhabited by the vicar; two pumps, known as the "town pump" and the "village pump," stand over the ancient wells and still form the water supply common to a number of cottages.

The estate is now in the possession of the Chaworth-Musters family. After Eadwald, Goda the Countess held it until the Conquest, when it was granted to Hugo-de-Grentemaisnil, one of the Conqueror's stout captains, and the greatest landowner in the neighbouring county of Leicester. Hugo left it to his son Ingleram, in the days of Henry I. From Ingleram it passed to his son Ranulph, and in due course to his son Fitz-Ranulph. Fitz-Ranulph's son Robert, Lord of Norton, Alfreton, &c., was the founder of Edwalton Church and also of Beauchief Abbey, where he and his son William [also a benefactor] are buried. His grandson Robert [de Alfreton] succeeded, 1242-1270, and his only son Thomas dying without issue in 1269, his daughter and co-heir Alicia brought the estate to the Chaworths by her marriage to Sir William-de-Cadurcis, a descendant of another warrior who came with the Conqueror from Brizay in Touraine—Cadurcis being the latinized form of the English name Chaworth, while both were derived from the old home in France "Le Chateau de Chaources."

The eldest son of the marriage, Thomas Viscount Chaworth was lord of the manor, 16 Edward I. According to Inquisitiones P.M. George Chaworth held it until 13 Henry VIII. when it passed to his son John. We find another George Chaworth, the last of the male line, in occupation of the manor-house at Edwalton for two years prior to his death [July 23rd, 1791]. The sole heiress, his little daughter Mary Ann [born 1786] continued to live there with her mother until 1794 when "Madam" Chaworth was married, at Annesley, to the Rev. Wm. Clarke, Incumbent of Annesley, Gonalston and Tythby. While at Annesley Lord Byron became enamoured of the heiress and immortalized her in verse as the "beautiful Mary," but on the 17th August, 1805, she was married at Colwick to John Musters, who thereupon assumed the name of Chaworth-Musters.

The estate thus fulfilled the adage "It came with a lass and it went with a lass." Three years after Mary's marriage her mother became a widow for the second time [1808], when she returned to the manor-house where she lived until her death, 14th July, 1829. "Mary" thus became a familiar figure in Edwalton, not only in the days of childhood, but in later years also, and this has given a touch of romantic interest to the village and the church which she loved so well.

"Encircled by trees in the Sabbath's calm smile

The church of our fathers—how meekly it stands;

O villagers, gaze on the hallowed pile—

It was dear to their hearts, it was raised by their hands.

Who loves not the place where they worshipped their God?

Who loves not the ground where their ashes repose?

Dear even the daisy that blooms on the sod,

For dear is the dust out of which it arose."(Robert Storey, a Yorkshire peasant poet, 1835.)

To the casual wayfarer, Edwalton Village, with its little church surrounded by dark hued coniferous trees, and mantled with ivy, is either passed by without notice, or looked upon as but a feature in a rural landscape; but to the student, and the lover of antiquity it makes an eloquent appeal.

The "oldest inhabitant" speaks with fond regret of the "stud and mud" cottages, the village smithy, the "Blue Ball," notorious as the haunt of poachers, the parish "land," the poor-houses, the pinfold and the stocks, the parish oven wherein bread made from "the gleanings" was baked, and the feasts of "frumenty" at harvest time, but these have now all passed away.

(1) Fragments may still be seen in the vestry.

(2) The painted Decalogue, Belief and Lord's Prayer, were executed by Robert Rowbotham, junior, of Bunny, at a cost of £8 [April 6th, 1801], They are a good example of the work of that period; the Belief and Lord's Prayer were removed to the tower in 1894, but the Commandments still occupy their original position. (3) Fragments may still be seen in the vestry.

(4) 1782. "Pd. Mr. Saxton for repairing bason 5/-." "1789. Pd. for the Basson 13/-." This is the last entry in the accounts connected with musical instruments.

(5) [1783. " Pd. for the cup mending 4s, 6d."]

(6) The vicar has made a transcript of the gravestone inscriptions for the use of members of the Thoroton Society. He has also made a copy of the parish registers.