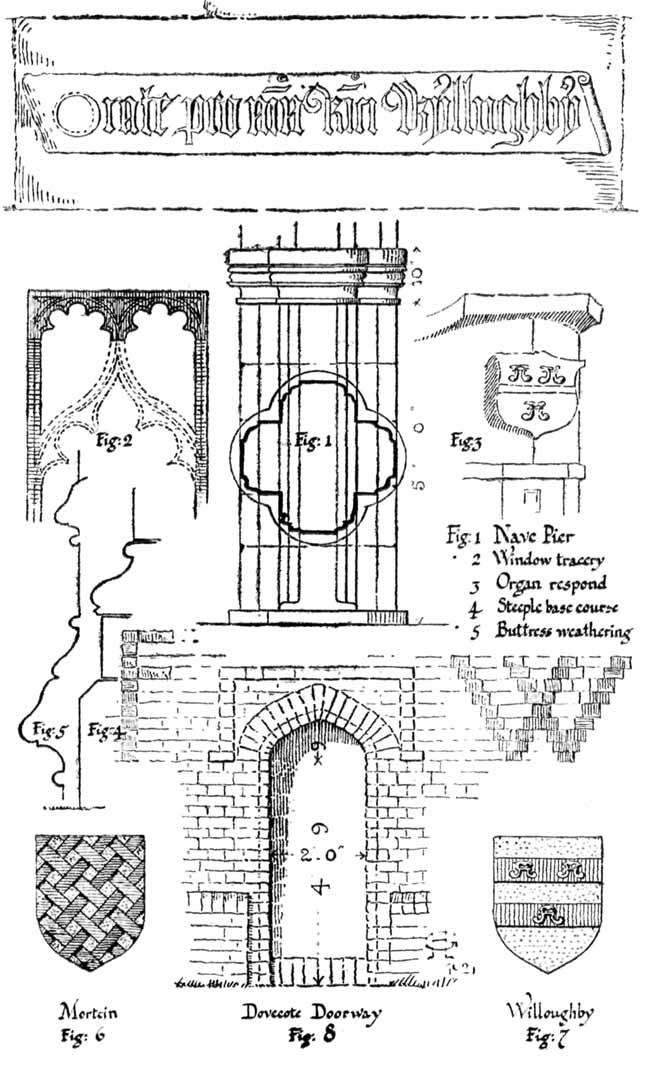

In making comparisons it should be noticed that where the window tracery and mouldings are original, the work is in conformity with Barton and Wilford, but where it has been renewed in modern days, identity is lost because the profile of the mouldings has been changed, and the tracery has been copied from an incomplete model from which the ogee sub-arch and featherings had been previously removed by damage or decay. (See plate II. Fig. 2).

Plate II.

The priest's doorway has suffered in like manner by the excision of the inner member of the moulding.

It would appear that the body of the church was not entirely pulled down and re-built, for the north pier arcade and three bays of the nave are not in harmony with the rest of the work. (Plate II. Fig. 1). This portion is almost identical in style with the mortuary chapel of St. Nicholas at Willoughby-on-the-Wolds, c. 1340. However helpful it may be from an historical point of view, one cannot help feeling that it was a mistake from the aesthetic point of view to utilize, by incorporation, this slightly older work, for the clumsily moulded piers, irregular in height, with ill-fitting, disproportionate capitals worked in the vernacular by village masons, must always have stood in sharp contrast with the refined detail of the newer work, which bespeaks craftsmen trained in a wider school.

The remodelled nave was lengthened by one bay, which caused the western face of the steeple to abut upon the public roadway. Seeing that instructions for a processional pathway all round the church had been recently issued (1348) the builders could only comply by carrying the north and south walls of the tower on arches and thus making the pathway run underneath the steeple. The north archway was blocked up for a time after the Litany processions fell into desuetude, and opened out again in 1885-6.

The belfry is approached by a vyse formed in the thickness of the wall, at the south east angle of the steeple, lighted by three narrow slits; the intermediate one which opens in the west wall of the nave is sometimes mistaken for a hagioscope. The western entrance to the church is between the steeple archways; the door is still secured by the original oak beam which slides in a deep slot in the wall, as it does at Barton-in-Fabis.

The steeples at Wollaton and Barton are nearly alike save that the buttresses at Wollaton are diagonal, while at Barton they are rectangular. A similar steeple, but smaller in size and without buttresses, is the only ancient portion of the work left of the chapelry of St. Catherine, at Cossall, in the same lordship.

An original 14th century doorway, now blocked up with masonry, has been re-set in the wall of the north aisle amid an almost continuous range of Tudor windows.

I think the influence of Lenton Priory may be clearly seen in the work under notice. The suggestion is strengthened by the fact that although the priory buildings are almost entirely demolished, the foundation walls and diagonal buttresses of the chapel of the Hospital of St. Anthony within the precincts, founded c. 1330, which now forms part of Old Lenton Church, and fragments re-used in building the modern churchyard wall, suffice to shew that 14th century additions to the great priory were carried out in the same architectural style, and built with stone from the same quarries as the work at Wollaton, &c.

The only quarries hereabout from whence coal-measures sandstone could be obtained in the 14th century, was an outcrop on Trowell Moor, midway between Wollaton and Cossall, on land originally belonging to the Morteins, and granted by them to Lenton Priory.

The plan of the church as it stands to-day (see plate I.) clearly reveals that, beautiful as it was in conception and complete in every detail appertaining to a village church, it did not retain its pristine form and dimensions for any length of time.

The first alteration was made after the death of the wife of Richard Willoughby in 1467. Hitherto the place of sepulchre of the Willoughby family had been at Willoughby-on-the-Wolds. Richard Willoughby in his will, dated 1469, desired to be buried "at the end of the high altar, on the north, before the image of St. Leonard, against the new monument he himself had lately built."

The erection of this monument, and of the adjoining Willoughby chapel, necessitated the removal of part of the north wall and the mutilation of its windows. The back of the tomb projects beyond the original face of the wall. There is a beautiful black-letter inscription cut upon one of the external facing stones, requesting prayer for the soul of Richard Willoughby (see plate II.). The western end of the north chancel wall, is now pierced by an arch, and contains the organ screen. An incomplete rendering of the arms of Willoughby is carved on the capital of the western respond. (Or—on two bars gules three water bougets argent). Plate II. Figs. 3 and 7.

If there ever was a chancel-arch—and the absence of such a feature was very unusual in the midlands—all trace of the arch and its responds has entirely disappeared.

When Sir Henry Willoughby died (1528) the south wall of the chancel was cut away in like manner to provide a monument for himself and his four wives. This involved the destruction of two-thirds of the sedilia. A small chantry was erected on the south side of the tomb. This fell into decay after the Suppression, when the space between the mensa of the tomb and the soffit of the arch was filled with brickwork, leaving the lower part of the south side of the tomb external. The "Hall Pew" was erected in 1885-6, on the site of the chantry, incorporating the old priest's door, and the blocking on the south side of the tomb was then removed.

The Willoughby tombs1 have already been described and illustrated. It is not necessary to refer to them further than to point out how they illustrate the way in which one piece of work may be interpreted by another. The tomb which Richard Willoughby caused to be set up at Wollaton, is repeated in almost every detail in the neighbouring church of All Saint's, Strelley,2 save that the cadaver is omitted and the brasses3 have given place to alabaster effigies. John Strelley (ob. 1500) married Sanchia, daughter of Robert Willoughby (ob. 1501) and thus there need be little doubt that both tombs emanated from one and the same workshop.

A secular building which stands on the western side of the turnpike road, between the church and the old rectory, is now difficult to allocate. Of mouldings, or other architectural features by which a date might be ascertained, there are none, but if we may judge by the ashlar masonry it is co-eval with the Willoughby Chapel (now the vestry) on the north side of the chancel. The building is generally spoken of as the old manor house, the home of the Willoughbys prior to the erection of the stately Elizabethan house, 1580-1588.

But this suggestion is not supported by facts. It is more likely that the ancient manor house was on the eastern side of the road, near to the present rectory. Traces of the adjuncts of a manor house still linger thereabouts in field names, &c.; there is a large fishpond in the vicinity, also a rectangular brick dovecote, now denuded of the ledges and nesting boxes and used as a stable. The initials F.W. picked out in dark coloured "header" bricks on either side of a Tudor doorway (Plate II., Fig. 8.) do not fix a definite date, as there were six owners of that patronymic in succession. From the style of the work however, I should attribute it, not to the Francis Willoughby who built the great house, but to his son, who died 1665.

I am inclined to think that the old secular building in question is the remnant of the chantry house " lately built in Wollaton by the Rectory house" (i.e. the old rectory, not the present rectory) "the lower storey whereof was occupied by Bede-folk, and the upper storey by two chantry priests," which Sir Richard Willoughby gave when he founded the chantry of St. Anthony at the high altar 13th December, 1470 (see Chantry Certificate Rolls—Thoroton Society Transactions, Vol. XVIII.). Or it may have been built for the old Grammar School, at one time looked upon as a rival to Nottingham Grammar School. "19th Feby., 1472-3. Master Thomas Lacey, master of Grammar School at Nottingham, covenanted with Sir William Cowper, of Wollaton, that during his life Sir William should teach 26 boys or men the art of Grammar in the town of Wollaton but in no way exceed that number." See Memorials of Southwell Minster, by Arthur Francis Leach, M.A., F.S.A.; also Victoria County History of Notts., Vol. II., p. 217: and discussions on the subject in the pages of The Forester.

(1) Transactions of Thoroton Society. Vol. VI., p. 37.

(2) Transactions of Thoroton Society. Vol. X., p. 15.

Arms, Armour, and Alabaster. By G. Fellows, pp. 25, 27, 28.

(3) Notts. Monumental Brasses. By J. Bramley. Transactions of Thoroton

Society. Vol. XVII., p. 121.