Following in chronological sequence, the completion of the steeple next claims our attention. There are certain indications which make it obvious that a spire formed no part of the intention of the original builders. Anyone who cares to climb the inelegant ladder which leads into the belfry, with its three bells, will get confirmation of this suggestion.

The neighbouring churches of Gotham and Normanton-on-Soar, impropriate respectively to the Abbey of St. Mary-de-pratis, Leicester, and the Prior and Convent of Durham, had already been thus embellished, and emulation spread to Radcliffe. Gotham steeple was probably built from base to summit as one effort. If so, it was the earliest stone spire to be built in the county. The change from the square of the tower, to the octagon of the spire is a simple splay, such as a carpenter of an earlier period would have devised in building a timber spire.

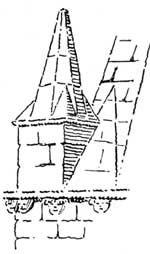

At Normanton, and here at Radcliffe, the spire appears to have been added as an afterthought. In order to roof-in the space intervening between the square plan of the tower and the octagonal plan of the spire, a mason’s method of a half-pyramid, or broach, is employed. At Radcliffe, in addition to the broach, each angle of the tower is carried up and finished with a pinnacle fashioned like a miniature spire. This adds greatly to the stability of the structure and also takes away the bareness at the springing line. These three spires, Gotham, Normanton, and Radcliffe, form an interesting study in the early development of spire design.

At a later date steeples were designed having a pathway and parapet all round at the base of the spire, so that the junction between tower and spire was not seen from below. Kegworth is a case in point. The tower at Kegworth was almost indentical with Radcliffe-on-Soar, until well on in the Decorated Period, when heavy rectangular buttresses were added to support an additional stage, and a tall tapering spire within an embattled parapet.

The third development of this church took place at the end of the 14th century. Attempts had been made from time to time by the Pigots, lords of the manor of Ratcliffe, to recover the advowson of the church from the convent, but without success. A change in ownership was made however, in 1381, and formally confirmed in 1409-10,when the Abbot and convent of Norton released the advowson and1 re-leased it to the Prior and convent of Burscough (Lancashire). The list of Rectors and Patrons makes it clear that whereas Norton had appointed Rectors from 1270 onwards, Burscough presented Thomas de Basford to the Vicarage in 1385, and thenceforward.

No sooner was this transfer effected than the nave and aisles were remodelled and brought to the present plan; albeit in modern times the north arcade and the aisle has been again rebuilt and reduced in width; this is shewn by the debased architecture, and by the fact that the northern respond of the arch leading into the miscalled Sacheverell oratory or chapel, is crippled.

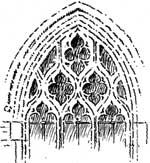

The large three-light windows in the south aisle— two in the south wall, and one (now deprived of its mullions and tracery) in the east end—belong to this enlargement, and indicate that by this time the Decorated style was well advanced; for the reticulated or net tracery does not follow geometrical lines throughout, but, for a short distance in the sides of the uppermost light the enclosing lines are straight and quite perpendicular2. The twin-window at the west end of this aisle

differs very materially in detail from the twin-lancets in the chancel, and obviously belongs to this period also. The Early English porch which covered the south doorway was enlarged to an abnormal size, and covered with a good oak roof. There is a scratch dial on its eastern buttress, and the inner walls are incised with numerous interesting devices and initials, and freely scored with arrow-marking.

A north doorway, in line with the porch doorway, formed part of the 14th century processional plan ; its position is still retained in the modern rebuilding, although now out of use.

The chancel floor is paved between the grave covers with 14th century monastic tiles, but alas ! their encaustic patterns are nearly worn away. Stretton tells us that when he visited this church, nearly a hundred years ago, he found at least fifteen floor stones of late 15th or early 16th century date, with effigies and inscriptions thereon, but it is quite impossible to decipher any of them now. In the north aisle there is a grave cover incised with the effigy of a priest clad in alb, stole, maniple and cope, with a chalice and gospel book by his side; other detached fragments of stones which once covered Esquires and Ladies lie about in all directions, but the inscriptions are all more or less illegible.

The nave roof of heavy oak timbering with carved bosses is a late 15th century replacement of an earlier high-pitch roof, as indicated by the water-tabling on the east wall of the tower; the clerestory windows in the north wall, irregular and insignificant, were inserted when the north aisle was rebuilt. There is no clerestory on the south side. The position of the rood-loft is well indicated by a fragment of woodwork still remaining in the north wall. A communion table which now stands at the west end of the nave, against the apology for a tower screen, the font cover, and the altar rails are all post-reformation work of the Restoration period.

In no other church in this county can the development of alabaster effigies,—incised, and in the round— be studied so perfectly as here. A series of table-tombs erected to the memory of departed Sacheverells, illustrates the transition through a hundred years, from the ideal of the mediaeva1 “ Kervers” to the classical conceptions of a later school of craftsmen, under the influence of immigrant artists from the Low Countries.

Rad-clive, or Redhill has long been noted for its excellent alabaster, and the quarries hereabouts have supplied material, not for church purposes only, but also for chimney-pieces, columns, wall-linings and pilasters, which are to be seen in a number of houses in the neighbourhood:—Kingston Hall, Keddlestone Hall, Staunton-Harold, Stamford Hall, the chapel at Welbeck, and the Mausoleum at Brocklesby.

It is a fair assumption therefore, that the material used for the monument in this church is local, and I hope to be able to shew that the workmanship was local also; but let us first pause for a moment to enquire how it was the Sacheverells came to be entombed here.

At the zenith of his power, Humphrey, Duke of Buckingham, an aspirant to the throne, should Mary Tudor’s right be denied, had acquired the manor of Radcliffe-on-Soar. History records the fact that “he had the stroke of the axe” on Tower Hill from Henry VIII., 1521, and when his lands were escheated by attainder and sold, Sir Richard de Sacheverell, son of Raduiphus Sacheverell of Hopewell became the purchaser. Sir Richard died without issue and left the estate to Raduiphus, the youngest son of his brother John, of Morley, county Derby. He and his successors after him occupied the manor house for more than one hundred years.

Radcliffe-on-Soar. General view, showing tombs of Sacheverells. Henry (1558), Radulphus (1539), and Henry (1580).

A fragment of the old manor-house is incorporated in the imposing looking farm-house which stands by the south-western corner of the churchyard.