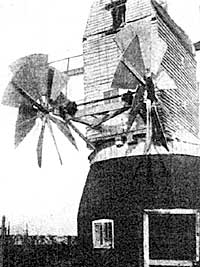

Fig. 9. Tower Mill, Alford, Lincs.

Fig. 10. Sack hoist drive, Attleborough, Norfolk.

I will now describe the sails or sweeps.

The earliest were of cloth or canvas fastened to a light frame of wood, these are shewn on the horizontal sweeps in Fig. 2.

In high winds the miller had to shorten sail and to do this each sail had, in turn to be brought near the ground.

If the sail frame is completely covered it is called full sail. Reefing is done by a deft manipulation of the sail lines being flicked behind one of three projecting sail bars on the trailing edge. The first bar is called "quarter sail" the second, "sword point," the third "dagger point."

The cloth sail is very unmanageable, though they are universal in Holland.

There is no control from the inside, and many accidents have been caused in gales since by trying to stop by the brake on the head wheel sparks are formed and fires result.

Sir William Cubitt in 1807, invented what is called the patent sail. This is composed of a number of pivoted vanes on each sweep. When shut they present a clear surface to the wind, but by an arrangement of cranks all worked in unison by the shutter rod they can be wholly or partially closed.

The operation of the vanes of the four sails is simultaneous and is effected by a long rod passing through the wind shaft, called the clothing rod. The end of this rod carries a spider connected to belt-crank levers, each one controlling a line of shutters.

These can be seen in the photo, (Fig, 5), at Parsham, Suffolk; also this shews the jack or fly very clearly. The other end of the clothing rod is geared by a rack to a chain wheel, thus allowing the vanes to be controlled by hand as desired, but in addition by adding a suitable weight or weights to the chain a safety device is introduced which permits a gust of wind to force open the slats by raising the balance weight. It is interesting to watch this weight moving up and down in a gusty wind, and the speed of the mill kept constant.

In some parts of the Midlands especially Nottinghamshire there is a type of vane control called the spring sail. This has the usual set of Cubitt vanes, but each sweep is controlled from the ground by adjusting the pressure by means of a laminated or coil spring.

Fig. 11. Governors, Costock, Notts.

Fig. 12. Tail wheel and stones, Gissing, Norfolk.

As to the number of sails. Many mills which have been designed for four or six sails are to be seen running with either two or four in the latter type; the reason being that the stocks of two have rotted and the miller has either been too poor or lazy to replace them.

Post mills always have four, but there are tower mills with three, four, five six and even eight sails. Fig. 9, at Alford shews a six sailed example, while at Heckington, Lincs, and at Peterborough we have eight sails. I regret I have no photos of these.

To describe in detail all the internal mechanism of a windmill would take the whole of the Transactions, so I may be excused if I only give a very short description.

The sack tackle is operated in many different ways. The most common is the slack belt principle.

This is well shewn in the photo of the arrangement of the Attleborough, Norfolk mill, Fig. 10.

The governor or regulator controls the runner stone by means of levers on to the liter bar, its action being to allow the stone to come closer to the fixed one when the speed increases, and vice versa. Fig. 11, at Costock, Notts.

Fig. 13. Newton, Notts.

Fig. 14. Tuxford, Notts.

Fig. 12 shews the tail wheel, wind shaft, two tail stones, vats, hoppers, sack tackle chain, rope etc., in the fine post mill at Gissing, Norfolk. This gives a good idea of the cramped space inside.

Fig. 3 shews the post, quarter bars etc., of the Costock mill.

Fig. 13 shews the spring sails at Newton, Notts, and Fig. 14 shews the unique fly tackle at Tuxford, Notts.

One other detail which I consider to be very interesting is inscriptions; in many mills we find them literally covered. I don't mean the modern initial date fiend, but the old millers inscriptions and the millwrights initials. At Costock the date is W. S. 1766.

In one mill, Haughley, Suffolk, I read the following, "Harry Sore, Haughley, aged 18 in February 1884, at this time of the year 1884 there was an earthquake when Harry Baker was miller and Harry Sore carter, and it stopped the mill which Harry Sore was clothing," (i.e.—furling the canvas on the sails), £10,000 damage was done in England.

Another good one. "The wages of sin is death," and at a later date has been altered to "The wages here is rotten." Finally, at Hingham, Norfolk we read "J. Wimer worked for Mr. Winkles 4 years and a half— What a mug."

To conclude, I deplore the awful destruction of these beautiful structures and one has only to tour in Nottinghamshire to realise what we have lost. Costock a grand example is now a beautiful ruin, and at Cromwell a tower mill is rapidly becoming the same. Tuxford we have a post mill, now out of use, and soon it will disappear. Here there were four working, three tower and this post mill. Two are merely shells, and the remaining tower lost a sail only a few months ago.

I am indebted for much in this article to Mr. H. O. Clark of Norwich who has with unbounded enthusiasm aroused the interest of the public in Norwich, and through this has acquired the lovely post mill at Sprowston, Norwich.

Can we in Nottingham do the same, acquire and preserve one of the few left in our County ?