There are some indications of a re-construction of camp-buildings in stone after the disastrous defeat of the Ninth Legion by Boudicca in 61 A.D., but they are very fragmentary, merely consisting of disconnected traces here and there of footings, for at the beginning of the Second Century the Romans thoroughly dismantled the camp and razed it to the ground, even removing foundations.

To the north of the Via Quintana, however, I found the foundations of a wall, the stone slabs being set obliquely in the clay to prevent foundering, and a roughly paved verandah in front of this wall. A shaft of a small column of Lincolnshire limestone (reddened by fire), which had been thrown down a neighbouring well, may have belonged to this verandah; this pillar was flat at the back, evidently forming a pilaster against a wall and it had a rectangular notch cut in the upper side, probably to support a horizontal beam of wood extending from one pillar to another.

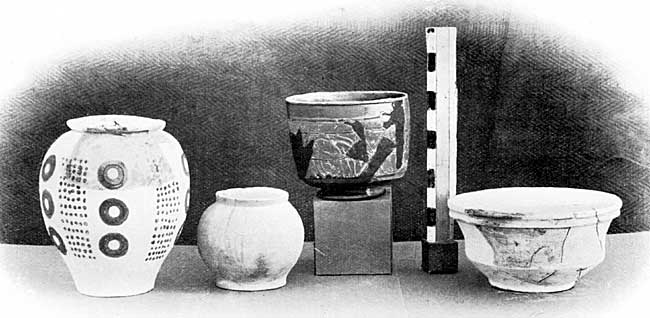

Just to the north of this wall there is a mass of stones filling an old cellar, and among the slanting flagstones I found a coin of Vespasian, a cylindrical "Samian" bowl (Forn 30) decorated in the style of the Domitian potter MERCATOR (some of which I also found in a well at about 20 yards distance), a white bowl in imitation of the carinated "Saiman" bowl (Form 29), and a white urn with barbotine decoration in brown circles and dots in Belgic technique (Plate XVIII.). All these objects indicate that the filling up of this cellar took place when the camp was dismantled and levelled, as already mentioned; for, owing to the campaigns of Cerialis against the Brigantes in the north and the advance of Agricola into Scotland, the military centre of gravity had shifted far to the northward, and MARGIDUNUM ceased to possess any further military significance. Ditches, pits and wells were filled up with camp rubbish, the Fosse Way was straightened to follow its present course, and driven arbitrarily right through the camp, over-riding the camp roads and old foundations; and MARGIDUNUM became merely a posting-station on the route from Leicester to Lincoln (See plan).

PLATE XVIII. Pottery from the old cellar.

A grave-group of about this period came accidentally to light in the ploughing of a field at some distance to the east of the camp, and unfortunately some of the urns were broken up by the farm-labourers in their mistaken search for possible treasure. A potter's stamp on a "Samian" cup (Form 33), REBVRRI OFF, i.e., the workshop (OFFICINA) of REBVRRVS, is of Trajanic date, so that the grave may probably be assigned within the decade 110-120 A.D. The remnants of the burnt bones in a cooking-pot indicate a young person, perhaps a girl, and this surmise is supported by the fact that both the jug and the small brown rouletted drinking-cup are diminutive (Fig. 3). A brown rouletted urn contained oysters and mussel shells as food for the spirit, but no coin was present. (The "Samian" vessels are drawn to twice the scale of the coarse pottery).

FIG. 3. Grave group.

It is evident that some wells would, in spite of the general levelling of the camp, be kept open for the use of the posting-station, and I found that some rubbish-pits and a stone-lined well were only filled up at the end of the Second Century. This well only contained pottery of Second Century date, mainly Antonine with a "Samian" cup (Form 33) stamped SECVNDINI M, probably Hadrianic. The stone-lining rests at its base on oaken beams, still quite sound, and the stones have in course of the long lapse of time been coated with a soot-black deposit of manganese oxide. I have not, however, found any buildings of Antonine date in the field which I am able to excavate; and in the rampart-area there is a natural deposit, feet in thickness, absolutely devoid of pottery or charcoal, and indeed containing unbroken fragile land-shells, pointing to the fact that for about 200 years a great part of the camp lay fallow and the earthworms were able to form this amount of soil without any admixture of camp-rubbish from about 150 A.D. to 360 A.D. Probably nearly the whole camp, with the exception of the mansio or caravanserai of the posting-station, became pasture-land for the post-horses, which would be about 50 in number.

Wells were of course still necessary for watering horses, and I found an interesting stone-lined Third Century well, which, judging from the pottery in the clay-ramming behind the stones, could not have been constructed before the beginning of the Third Century, and by the evidence of coins must have been filled in at the beginning of the Fourth Century, perhaps as a result of the troublous times when the usurper Allectus was defeated and slain by Constantius Chlorus in 296 A.D.1 At a depth of 10 feet I found an interesting association of flagons (two of them still perfect), with a much-corroded coin of Tetricus Senior still adhering to the inside of one of them (Plate XIX). A coin of Carausius in good condition was also associated with these flagons. Their date is also determined by the fact that one of them closely resembles a flagon of the Blackmoor hoard, the coins of which, amounting to many thousands, were not later than Allectus and probably formed part of his war-chest. At the base of the well there occurred some "Samian" ware that can be dated to the beginning of the Third Century, a wooden comb, a circular bronze brooch, once enamelled, but the enamel has perished, and a collection of earthenware roundels probably used for the game of five-stones or "snobs," as it is called locally, for the children of East Bridgford (in whose parish MARGIDUNUM lies) still cut out roundels of pottery for this game, just as in Roman times.

PLATE XIX. Pottery of third century well.

(1) For a detailed account of the pottery, etc., found in this well, see my "Pottery of a Third Century well at Margidunum," Journal of Roman Studies, 1920, Vol. xvi., 36-44.