Haughton Chapel

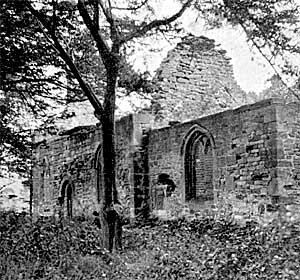

The roofless ruin of Haughton Chapel, c.1915.

By THOS. M. BLAGG, F.S.A.

THIS ancient chapel is dedicated to St. James, and as parts of the present building, such as the fine south doorway, belong to Norman times, it seems evident that it served as a parish church to a small village prior to the depopulation of the place by Edward Stanhope’s Enclosure of 1509, when he brought it within his park and it became a mere domestic chapel to the hall.

Haughton is one of the chapels mentioned as an appurtenance of the great chapelry of Blyth which with others, such as the church of Harworth and the chapel of Serlby; the church of West Markham with the chapels of Kirton, Walesby, Houghton, Bevercotes, Drayton, Gamston and Egmanton; the church of East Markham; the church of Bridgford; the church of Lowdham with its appurtenances; the chapel of Gunthorpe and the church of Gonalston, were granted by John, Count of Mortain (afterwards King John of England) to the church of St. Mary at Rouen in 1191, together with certain lands in Nottinghamshire and at Tickhill; two-thirds of the tithe of garbs in the demesnes of Tickhill; half the tithe in the demesne of Marnham, and other revenues. These are set out in a copy of the original charter still preserved in the archives at Rouen and printed by Mr. Round in his Calendar of Documents preserved in France illustrative of the history of Great Britain and Ireland, 1899, p. 16.

According to the Torre MSS. at York, Sewall, Archbishop of York, on 11 Kal. Decbr, 1257, intervened to erect the vicarage of Walesby and secure that there should be from thenceforth one perpetual vicar residing there who shall understand English and shall be presented by the Chapter of Rouen, who were to retain the tithe garbs (i.e., the tithe of corn or great tithe). The vicar was to have the dues of the altar with the lands and meadows of the church and the mediety of the mansion towards the south, and "likewise the vicar shall have entirely the chapel of Hockton, with the garbs and other appurtenances to it, he causing the same chapel to be honestly served; in which respect the vicar shall bear all burdens ordinarily incumbent on the same church (i.e., Walesby) and chapel (i.e., Haughton) excepting that the Chapter of Rouen shall bear their proportion with the vicar towards the repairs and rebuilding of the chancels therein and the finding of books and vestments and other altarages." All of which was confirmed by the Chapter of Rouen in May, 1258. Thus it will be seen that Haughton was treated as a rectory (in that the incumbent retained the tithe of garbs therein) annexed to the vicarage of Walesby. Torre says of Haughton—"There is a chappell here at Hoghton dedicated to the honour of St. James which was accounted parcel of the cbapelry of Tykhill and served by the vicar of Walesby, who is rector thereof, having all the great tythes of the place."

The blocked up 14th century arcade is virtually all that remains standing of Haughton Chapel (A. Nicholson, 1982).

According to Walesby Terriers of 1726 and 1840, the vicar of Walesby held in Haughton Lordship a close called "Vicar Close" of seventeen acres (divided into two) and an acre of land in "Low Meadow," and that these had been settled to the Duke of Newcastle by a private act of Parliament, 7 Anne, 14 (i.e., in 1708) entitled—"An Act for vesting in John Duke of Newcastle and his heirs certain lands belonging to the Vicarage of Walesby" in return for annual rents of £10 and 12/- per annum for the above closes respectively for ever, and the Duke paid also £2 a year for the tithes of Haughton by an ancient composition, and the Vicar held besides a horse-gait for a mare and a follower, i.e., a mare and foal, in Haughton Great Park. This was doubtless a fair equivalent then, seeing that all Haughton had been dispeopled and inparked by the Stanhopes, and the tithe of corn was nil, but when at the end of the 18th century, it was disparked and much of it again became corn-land, the Dukes got the best of the bargain, while possibly the "vicar-rector" has not received any compensation for the loss of the amenity of running his mare or foal in the vanished Park.

Torre repeats that the chapelry of Walesby (with which he included Haughton) was, as part of the Chapelry of Blyth, given by John to the Archbishop of Rouen and adds—"and so it continued a free member of the Free Chappell Royal of Tykhill" till the deprivation of the alien churches when “it was given by King Henry VIII. to the See and Abbey of Westminster and at the Dissolution to the Earl of Shrewsbury and after to . . . now Marquis of Halifax."

Thus, we see how Haughton Chapel, from being a parish church, became a domestic chapel in lay hands.

This building has been in much the same condition of ruin in which you now see it for many generations. John Throsby when collecting notes for his edition of Thoroton, visited it about 1795 and says he found "a little pleasing ruin surrounded by a young plantation of trees" and he gives us an illustration of it taken from the north-east view-point. He also gives illustrations of the recumbent effigy of a lady which he says lay outside amid some rubbish and nettles, and a fine grave slab incised with a cross fleury from which also he luckily copied the lettering, now almost illegible. To these two monuments I will draw your attention presently. In the MSS. of the antiquary, Gervase Holles, preserved in the British Museum, we have further details of the monuments and inscriptions and particulars of the heraldic glass in his day in the windows. This would be just before the Civil War.

From the ruins as we see them to-day, we can deduce that there has been a church here centuries before the Holles bought the estate or even the Stanhopes became possessed of it, for the south doorway with its plain square-moulded circular headed arch on inside and outer arch with chevron ornament and outer order of cable moulding, and without jambshafts, is early Norman work. Adjacent to this doorway on the east side will be noticed a few courses of herring-bone masonry, while a few Norman stones can be seen reworked into the masonry of the gable above the chancel arch.

The Norman south doorway of Haughton chapel in the 1920s.

This Norman church was possibly a small structure, comprising chancel and nave without aisles. This building appears to have been reconstructed in the 14th century with complete north aisle; that to the nave having now disappeared, the north arcade of three bays being walled up—the capital of the eastern and part of the base of the westernmost of the two octagonal piers can be seen in the ruined wall from the interior, while from the outside of the church these are completely visible, the capitals having neck moulds and plain soffits and the abacus slightly ornamented by a striation of three lines. The bases are on the pattern of the capitals inverted, but with double base mould in place of neck mould. The pointed arches of this north arcade are of two orders with plain chamfers stopped by squinches. The north doorway has a plain chamfered pointed arch with deeply coved segmental hood mould which appears earlier than the doorway.

The south wall of the nave has two windows of two lights each, with quatre-foil heads. The west window is of three lights with bold cuspings, grooved for glass, below a coved hood mould, and flanked by 14th century buttresses. Above all is a gabled bellcote with spaces for two bells.

In the west window of the south aisle, a portion of the mensa or stone altar slab of the pre-Reformation altar, shewing one of the consecration crosses, has been used to block up the window.

Low side window, Haughton Chapel.

Turning to the chancel, we see an east window of two lights with rather nice trefoil heart in tracery at head. In the south wall of the chancel is a low side window, now blocked up, framed in slabs of Maplebeck sandstone with chamfered lintel and cill, the latter 18in. from the ground. Dimensions of aperture 2ft. by 1ft.

On the east side (exterior) of the south chancel window, near its shoulder, can be seen a circular object built into the wall, pierced by a hole in its centre. This appears to be a stone from a drain-shafted piscina. Above is a plain chamfered string-course or corbel table. Also in the south wall of the chancel is a trefoil headed piscina niche with drain, but with face of bowl hammered off. The niche is grooved for a credence shelf.

A wide and depressed arch on the north side of the chancel gives into the mortuary chapel and has apparently replaced the original north arcade which is indicated by a respond still remaining at the east end. The mortuary chapel, now much in ruin, appears to have been built on to the north side of the chancel in about the time of Henry VIII., presumably by the Sir William Holles who built the greater part of the hall, on the doorway of which he placed the date, 1545. This would be about right for the date of this addition, for it is not bonded into the main fabric of the church, and besides this depressed arch into the chancel, it has independent access from outside through a west doorway with depressed Tudor arch, plain chamfered.

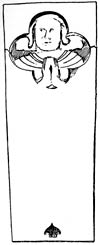

So much for the fabric. To come to the objects in and about it, we have first a plain circular Norman font, thirty inches in external diameter, lying uncared for at the west end of the nave. Then outside the south door is one complete grave-slab and the head of another, having quatre-foil sinkings containing heads and a pair of hands clasped in prayer, presumably from the tombs of early priests. There is a stone with foliated cross-head lying under the chancel arch. Then there is the stone lying in the nave with the fine cross fleury and shewing traces of an inscription in Gothic lettering. It is now decayed and choked with moss, but Throsby gives this inscription as

Jesu Mercye, Lady helpe,

divided by the arms of the cross, and on the stepped base or "Calvary" a shield of arms having a bend between six cross crosslets for Stanhope, impaling a coat, even then illegible; and below this the legend,

"Orate pro aia Johanne Stanhope uxor henrici Stanhope arm."

Effigy of woman.

Among the nettles in the mortuary chapel is the recumbent effigy of a woman, the head resting on a lozenge shaped cushion, superposed on a square one with tasselled corners. She is represented wearing the wimple or chin veil, so presumably was a "vowess." These were mostly widows of noble or gentle families who took a vow of chastity. This was a formal ceremony usually performed by a bishop, or by an abbot or prior commissioned by the bishop, who invested the vowess with a pall or mantle, a veil, and a ring, and the vow of chastity was taken in a set form of words. Thereafter she could continue to live in her late husband’s castle or manor house, or she might retire into a nunnery—not as a member of the order—but merely as a lodger still free to move about and attend to worldly affairs. Examples of the wording of the vow both in English and French, and a list of the vows recorded at York between 1374 and 1526 will be found at the end of Vol. III. of the Surtees Society’s Testamenta Eboracensia, and therein I find the vow of Elizabeth Stanhope, widow, taken before the archbishop at Scrooby on 19th August, 1459, and that, I take it, identifies the lady whose effigy we see.

|

|

Demi-effigy of a lady, Haughton Chapel, Notts. |

Demi-effigy of a man, Haughton Chapel, Notts. |