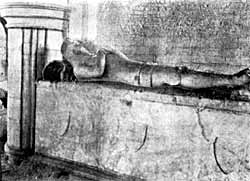

St Mary's church, Willoughby-on-the-Wolds. Effigies

of Sir Richard Willoughby.

St Mary's church, Willoughby-on-the-Wolds. Effigies

of Sir Richard Willoughby.In the north aisle are collected a number of ancient titles whose heraldry has been worked out by Mr. Parker in the Transactions for 1932 (p. 99). Close by is an oval floor slab to the memory of Colonel Michael Stanhope, son of the Earl of Chesterfield, who was killed in the fight at Willoughby on July 5th, 1648. A graphic account of this encounter and the events leading up to it is to be found in Nottinghamshire in the Civil War, Wood, p. 125, et seq.

The chief interest of the church is centred around the Willoughby mortuary chapel at the north-east of the church, and its array of funerary effigies.

The dedication of the chapel is to St. Nicholas, and this patron may have been chosen by a family whose wealth was based upon the fortune made by the merchant Ralph Bugge, because St. Nicholas, amongst other things, was the patron saint of merchants and traders. The 14th-century architecture of the chapel is simple. It is a plain oblong on plan and its floor is sunk a few inches below the present floor level of the church. It is separated from the north aisle by an arcade of two arches and at its west end is another arcade consisting of three arches now blocked up. Above this western arcade is a window, also blocked up. It looks as if there had been a north porch to the church from which access to the chapel might have been obtained through this arcade, and the window was set high, either to avoid this porch or, alternatively, to provide a view from a possible watching-chamber set above it.

The tracery of the windows is only interesting because the outside is flat-faced, a rather unusual feature. The east window is curious, for the sill is cut away to allow for the insertion of an altar slab above which provision is made for a reredos and a rere table. To the north of the altar is an aumbrey, and to the south a piscina, and west of the piscina is a stone seat which would be used as a sedilia by the cantor. The provision of this accommodation for a cantor as well as an officiating priest reflects the amplitude of the endowment of the chantry.

About 1240 a certain Ralph Bugge lived in a house at the corner of St. Mary's Gate and High Pavement, Nottingham. He was a wool merchant, and having made a fortune he purchased lands at Willoughby-on-the-Wolds and eventually was buried in St. Peter's Church, Nottingham. He had two sons, one of whom, Richard, came to live at Willoughby. Of his son, another Richard, Dr. Thoroton says “He increased his patrimony exceedingly and was a lawyer and very rich.” He directed that his body should be buried in the chapel of St. Nicholas, Willoughby, and as he died in 1363 this gives us a date for the erection of this chantry.

St Mary's church, Willoughby-on-the-Wolds. Detail of Madonna and Child on Sir Hugh Willoughby's Tomb.

Burial customs during the Middle Ages were somewhat different from those which obtain nowadays. One custom was the use of stone coffins which it was usual to sink a foot or two into the ground forming the floor of the church. They were closed by stone lids set flush with the floor of the church, and they were not meant for permanent occupation. Provision was made by means of which the body disappeared, leaving only the bones which were collected and deposited in an ossuary or charnel house, and the coffin left free for succeeding tenants.

After the Conquest the earliest form of a coffin lid was a flat stone a few inches narrower at the foot than at the head. If it bore any mark at all it would be a simple incised cross, often of the Calvary type—i.e. set upon steps. There would be no form of epitaph for the tenure of the coffin was only temporary. This plain incised marking was distasteful to the artistic sense of the 13th century and gave place to more elaborate treatment. The lids show a tendency to become coped, and the cross,

instead of being simple and incised, is carved in relief and is elaborated, particularly at the ends, which are twisted into fleurs-de-lis and other devices.

By the 14th century it was found that these coped stones were inconvenient for traffic, and so the lid becomes flat again but its shape changes to a plain oblong. From these flat stones it was no great step to the high-tomb, which was merely one of these flat stones raised a few inches from the floor. From this the table-tomb developed, a slab set upon a casket which not only held the body but afforded space for the display of heraldry and other enrichments upon the sides and the ends. The final phase came when chantries became popular and masses were said at consecrated tombs which thus became altar-tombs.

St Mary's church, Willoughby-on-the-Wolds. Effigy of Sir Richard Willoughby, ob. c. 1370.

Although at first no epitaph was used—or, indeed, possible—for the tenure of the tomb was temporary, the custom of marking the sex or the profession of the deceased by some conventional device gradually came into fashion. Thus, a pair of shears might indicate a woman, a chalice a priest or a sword a soldier. From this a development was the representation of a woman, a priest or a soldier by a few incised lines. With the artistic progress of the 13th century these humble conventions were quickly turned into something more elaborate, and figures—often carved in relief but with no attempt at portraiture—came into use. As time went on, these figures in relief were cut completely free and worked on the round and laid upon the grave-slabs as separate figures.

The earliest figures thus produced were hacked out of wood or local stone, and were not usually carefully finished. They were merely cores to be covered with a coat of gesso which, while still plastic was modelled to represent a costume, vestment or armour, and the whole was elaborately coloured and gilded, producing a most decorative effect. But they were ready-made figures and made no attempt at portraiture.