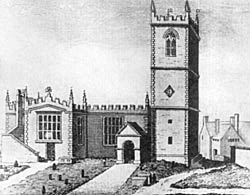

Fig. 5. Deering's view of St. Nicholas Church from the north, published in 1751, and showing the church before the addition of the north aisle in 1783.

Originally, as may be seen from Deering's illustration published in 1751 (Fig. 5) the church was cruciform without aisles but with a north porch and a western tower. But it was the parish church for the fashionable quarter of Nottingham, for many of the neighbouring gentry had their town houses in Castle Gate, some of which still remain. St. Nicholas' became popular with a fashionable congregation and earned for itself the nickname of "The Drawing Room Church," and its accommodation became too strait for its worshippers. This does not necessarily mean that great crowds attended its services for it is difficult to see where great crowds would come from in eighteenth century Nottingham, for the population would probably not be more than about 6,000 to 8,000 and there were three parish churches and a number of dissenting places of worship.1 The difficulty may even have been brought about by the fashion in dress then prevailing, for the eighteenth century was a time when voluminous skirts developed for both ladies and gentlemen and much room was needed for their accommodation.

Fig. 6. St. Nicholas Church, Nottingham, from the north, showing the tower built 1671-1678, and the north aisle added 1783.

Hine tells us that aisles were added to St. Nicholas' in 1733,2 but this is manifestly wrong for Deering's view of 1751 shows the church without aisles. Blackner tells us that the south aisle was "extended" (which probably means built) by means of voluntary contributions in 1756 and that in 1783 the north aisle was also extended at a cost of £5003 (Fig. 6). It would appear that galleries were added to the church about this time, of which one at the west end of the south aisle remains. Square pews were also fitted into the church during the eighteenth century and some idea of their woodwork can be gathered from the contemporary panelling which still remains in the chancel. In 1811 a small organ was erected in the church and the striking and unusual pulpit seems to date from this time. It fits clumsily upon its feet and evidently was not made for its present position but its origin is unknown. In style, it is not unlike the furniture from the archdeacon's court in St. Peter's. In 1848 an organ chamber was built to accommodate an organ bought from the Roman Catholic church in George Street, and the present gabled roof was set up over the nave. Although quite effective this roof, which doubtless replaces either a flat ceiling or a roof of very low pitch, is out of keeping with the rest of the church but is particularly interesting as an example of the Gothic Revival in the architecture of the mid-nineteenth century (Fig. 7). In 1863 a complete remodelling of the interior of the church was undertaken. The present pews were set up and the galleries, with the exception of the one at the west end of the south aisle, were removed. The fronts of these galleries were used to form choir stalls which have been replaced by those now in use, but a portion of the old gallery fronts will be found by the north-west door.

Fig. 7. Interior of St. Nicholas' Church, Nottingham, showing the graceful chancel-arch and the roof over the nave set up in 1848.

In order to appreciate the beauty of St. Nicholas' church it is necessary to examine it from an eighteenth century point of view and not with the same standards as would be used in the appreciation of a Gothic building. If this viewpoint be accepted, St. Nicholas' church will be found to be an exceedingly comely structure. Upon entering, its spacious dignity is at once evident and the incongruous roof of the nave in no way detracts from its dignity which owes its beauty to the just proportions of the nave and aisles, and the height of the building. The pews, whose arrangement must be singularly awkward for the internal traffic of the church, are reminiscent of the early days of Queen Victoria, and the whole building is illuminated by a flood of light admitted through excellently proportioned windows of three lights with segmental heads, typical of the eighteenth century. It will be noticed that the south aisle extends further westward than does the northern aisle.

Fig. 8. Detail of the altar rails and altar datable to 1752.

But attention is quickly concentrated upon the chancel, which, eliminating the modern furnishing, is a beautiful structure redolent of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The four-centred chancel arch is exceedingly graceful and the beautiful proportions of the chancel are enhanced by the dignity of the panelling and the magnificently moulded ceiling with its massive consols. The altar rails and sanctuary chairs are excellent examples of eighteenth century woodwork (Fig. 8) and fortunately it is possible to date them with close accuracy. Blackner tells us that in his time, about 1815, a hatchment was preserved in the church bearing the arms of Sir George Smith.4 Hatchments were prepared at the death of a person whose arms they bore and, after being displayed outside the residence of the deceased for a certain time, were deposited either in the parish church or the church that the deceased attended. Sir George Smith, then, was a member of St. Nicholas' congregation. He was a member of the well-known banking family of Smith whose ancestral business with its premises at the corner of South Parade and Exchange Walk is now merged into the National Provincial Bank. He changed his name to Bromley, and built Bromley House on Angel Row. A date-stone in the garden of Bromley House tells us that it was built in 1752, and as the design of the altar rails at St. Nicholas' is so closely akin to that of the balusters and handrail of the staircase in Bromley House, we may date this exquisite workmanship to 1752—about the time of Clive's conquest of India.

Upon examination, it will be found that these altar rails return upon the north and south walls of the chancel in a meaningless manner and that the credence table is bow-fronted. If the handrail be examined it will be found to have been cut, and there is also a joint in the run of the balusters. All this seems to indicate that the credence table is made out of a part of the old altar and that the altar was originally enclosed by a three-sided pen formed by the present altar rails, an arrangement which would accommodate a great many communicants at once, or alternatively give ample room for the voluminous dress of each individual.

Over the two northern doors are blazons of the royal arms which are exceedingly interesting. Previous to the Reformation it was usual to set up a representation of the Last Judgement, which was called a Doom, on the east wall of the nave of churches, over the chancel arch. In front of this was the Rood Loft from which certain portions of the service were read, and which carried a Crucifix flanked by figures of St. John and the Blessed Mary. The teaching thus announced was that Our Lord on His Cross hung between sinners and the Judgement. A plain cross, typifying the Risen Lord was used on the high altar. The puritans thought these figures to be idolatrous and swept them away, leaving the Rood Loft empty and forlorn. The custom gradually arose of placing the royal arms on the Rood Loft to remind the congregation that the sovereign was the head of the Church of England, and a few royal arms previous to the civil war are still to be found in out-of-the-way churches. During the Commonwealth these royal arms were removed, but an act of parliament during the reign of Charles II enjoined that royal arms should be set up in all churches as an indication of the loyalty of the congregation, an indication which had a peculiar significance during the times of Jacobite activities.

1 For guidance as to the population in XVI. cent, see Wood, Civil War in Nottingham, p. 3.

2 T. C. Hine, Nottingham Castle, p. 28.

3 Blackner, History of Nottingham, p. 98.

4. Blackner, History of Nottingham, p. 99.