The Rosary.

A corner of the lake.

The Lime Avenue.

The terrace garden.

The lawn fountains.

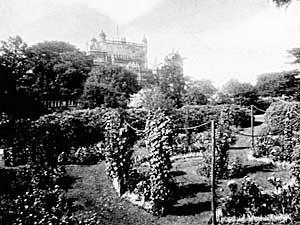

A distant view.

The park.

And now let us move down from the house, by the steps of the Saloon door, and wander across the green lawns of the balustraded terrace, down the old cracked and notched stairs to those lower flats which the cedars shade; and where venerable ilex of Jacobean times lean over the drop fence into the Park. Let us move to our left, past the French Hovel (why so called?), and look eastwards to Nottingham, past and beyond the long avenue of limes, with its fourfold rows of lofty pillars. How lovely that view can show, as the town climbs its slopes to the wooded heights of Mapperley, when the soft hazes of summer bathe alike the red brick and tile of buildings, and the variegated fields, gardens, tree-clumps, till they blend and fuse into very poetry of hue and shading! Aye, even the high chimneys become glorified, and lend a veiled dignity to the outlines; while the Castle, on its rocky pedestal, might be imagined a mediaeval fortress guarding its feudatories. Without much strain on the imagination, Nottingham, as viewed from the terrace at Wollaton, might in certain aspects, and on certain days, stand for a Southern city of dream-born and poet-planned creation.

Turning back across the grass, past the small fountain basin, where the rose-pink water-lily raises her coronal of bloom above a floating halo of bronzed foliage, we could almost wish the lawn were broken again into squares, as in the picture by Sibrects (time of Orange William) it is depicted; for the plainness of the well-kept sward, as now, is in somewhat bald contrast to the architectural richness backing it. So clear-cut still, by the way, is this rich detail of the house, despite its age, that when, in 1888, the Royal Agricultural Society of Great Britain held its meeting in Wollaton Park, the present Sit Walter Gilbey, observing the same, contradicted others on the date of the building, and made the bet of a new hat with some of the Council that it had not existed a hundred years. He lost his hat: that year was the house's tercentenary.

Leaving the house and its verdant fronting, we wander down a sloping path, shrub-bordered, past flourishing remains of more old ilex, and come suddenly upon a garden terrace, glowing in colour, lying between the great Camellia House (that monument of injudicious outlay, as wherein can one see the eight or ten thousand pounds spent on its erection?) and the ha-ha drop to the Park. In that Park roamed of yore the wild white cattle of Britain. Those of Wollaton were polled, and had black noses and insides of ears. From the fact of their being described as "spotted," and "good milkers," and "used for draught purposes," it is fairly certain that they had been crossed with domestic breeds; and that the seven sole survivors, which were destroyed by the seventh Lord Middleton, were not worth preserving, as but little of the original strain remained.

From this flowery parterre of the terrace garden, the sweep of grassy glades towards the lily-spread waters of the lake is a fair outlook ; and on summer evenings, when the deer, red and fallow, pass in stately or tripping bands by the sunk fence, the tiny calves and fawns frolicking lamblike, uttering their petulant, querulous cries, and wild-fowl and Chinese geese on the water call to their kind in blended voices — when church bells and clock chimes are the only sounds that tell of the vicinity of many multitudes, and the rich flowerage around gives forth its good-night perfume to the sinking sun — we, there standing, seeing, hearkening, sensing, envy none their environment.

Beautiful Wollaton — thank God for thee! But we end with a note of sadness, for "the trail of the serpent is over it all," as over all of earth. Sad are things many! Sad is the gradual creep of the city down to the Park walls; when the distance to lend enchantment will be absent from that view, when chimneys can no more appear as fairy spires, the gas-holders as mediaeval granaries, and the big factories with their hard iron-framed windows lose charming value as ruddy blurs through the hazes of blue. Sad is the nighness of the local colliery, which it was left to the last generation to plant in the pretty village itself; and whose smouldering pit-bank generates sulphur fumes which will surely in time do to death the noblest trees.

Quite in recent years the "Great Walk," planted from acorns in 1660, directly in front of the Hall door, has become chiefly a replacement in young timber; and all one can do now, throughout the Park, is to follow the old Scotch laird's advice to his son: "Be aye stickin' in a tree, Jock, — 'twill be growin' while ye are sleepin' !"