< Previous | Contents | Next >

|

|

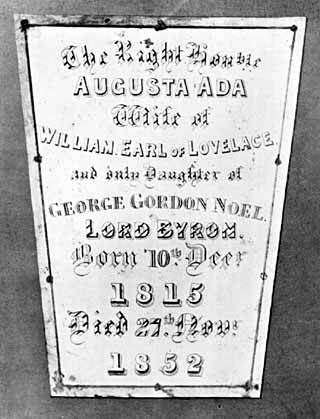

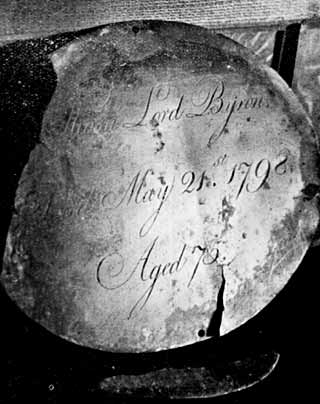

| The plate on the oak coffin of Lady Lovelace. | The plate on the oak coffin of the “Wicked Lord.” |

|

|

| A funerary ornament on Byron’s coffin. |

The Byron Slab in the floor of the Chancel of Hucknall Torkard Church. The marble was the gift of the King of Greece in 1881. |

|

|

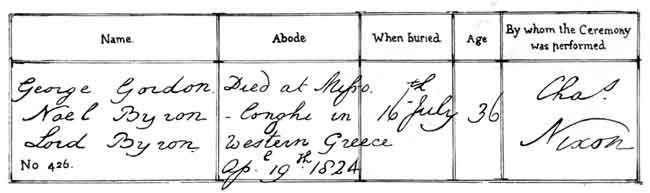

| The entry of the Poet’s Burial in the Register of Hucknall Torkard Church. | |

|

|

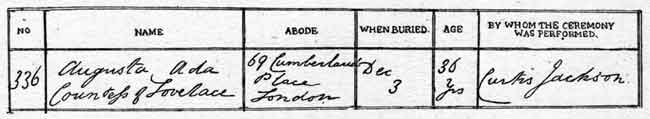

| The entry of the burial of Augusta Ada, Lady Lovelace. | |

There were no more coffins in this middle pile to be identified, that of the poet’s mother resting upon the debris. In my examination of this pile I was led to the conclusion that this middle space had been reserved for the adult female members of the Byron family, and that here on this spot the bodies of Cecile Ladie Byron, the wife of the first Lord, Elizabeth, the wife of the second, Elizabeth, the wife of the third, and of others, had crumbled to dust.

Continuing my investigations, I moved over to the south side of the Vault. The pile consisted almost entirely of debris, which was very much greater in depth than on any other part of the floor. This was undoubtedly the children’s portion of the Vault. Two children of Richard, the second Lord, and four children of William, the third Lord, were all buried here—and there may have been others—but all the children’s coffins in the Vault had perished, with the exception of the one leaden shell which I had previously found beneath the chest containing the heart and brains of the poet. It appeared to me that this had been removed from the south pile, and at some time placed under the east end of the chest to raise it to the level of the bottom step of the staircase leading into the Vault, upon which the other end of the chest rested. I could come to no other conclusion. It was impossible to account for the position of the coffin of this small infant in any other way.

In the south pile of the Vault there was one leaden shell that was intact resting upon the debris, and evidently not in its original position. There were no means of identifying it, but the dimensions led me to conclude that it contained the body of a female, and that therefore it should have been in the centre portion of the Vault. What was the explanation of its removal? It was a very small shell, and at the time when Byron’s mother was buried, it was probably the sole coffin intact in the second pile. I could only conjecture that when the Vault was opened in 1811, it was found that this small coffin would not provide sufficient support for the much larger and heavier coffin of the Honble. Catherine Gordon, which would have normally been placed upon it, and that it was then moved to the south side of the Vault to allow the weightier coffin to rest on the debris. This explanation alone accounted for the fact that under the coffin of the poet’s mother there was no other in a partial state of decay.

I wondered whose body this shell, in the third pile, might contain. The discovery on the top of the coffin of the “Wicked Lord” of a leaden plate, bearing the name of Lady Mary Egerton, the first wife of the fourth Lord, and who died in 1703, led me to think at first that it might be her coffin, but bearing in mind that the second wife of the fourth Lord, Frances, the daughter of the Earl of Portland, was buried in the Vault nine years afterwards, and that her coffin would be placed on the top of that of Mary Egerton, I came to the conclusion that it was more likely to be hers.

My task was completed, and I ascended the steps of the Vault. I had satisfied myself that there was no evidence of there having been a crypt beneath the Chancel of the Church, and I had exploded the theory that the body and the heart of the great poet were buried elsewhere.

Only one more matter remained to be cleared up. Was the Vault, as I had seen it, the Vault as it had been originally constructed, or had it, before the enlargement of the Church in 1887-8, extended under the Chancel floor? To determine this it had already been decided that another work of excavation should be undertaken on June 22. There was no necessity for the Vault, or that part of it which I had explored, to remain open for this further undertaking; in consequence, in the early morning of June 16 the workmen restored the old slab to its original position, and the work was so skilfully done that there is no evidence of its having been removed.

In the evening of June 22 the masons made a hole about five feet square in front of the Chancel steps, and proceeded to tunnel under them.

The work of tunnelling went forward slowly, and with difficulty, but in about two and a half hours I had satisfied myself that there was not, and never had been, an extension of the Vault on the north side.

During these operations I found, immediately under the Byron Tablet in the Chancel floor, and under the shadow of the north wall of the Vault, a body which appeared to be that of an old man. I ventured to conjecture that this was the body of Joe Murray, the faithful servant of Newstead Priory, of whose burial in the Church, in close proximity to the Vault, we have the evidence of Washington Irving.

After making this discovery, I gave orders to the masons to discontinue the work of excavation, and to start to fill in and replace the tiles.

Pilgrims from all parts of the world visit the Church of St. Mary Magdalene, Hucknall Torkard, to pay homage to the memory of Byron. As they stand beside the Vault, they may well breathe a prayer that all those whose bodies lie within its walls, may enjoy the realisation of the hope so beautifully expressed in the words of the Poet: —

"If that high world which lies beyond

Our own, surviving love endears;

If there the cherished heart be fond,

The eye the same, except in tears;

How welcome those untrodden spheres!

How sweet this very hour to die!

To soar from earth and find all fears

Lost in Thy light—Eternity