< Previous | Contents | Next >

Cranmer's Village

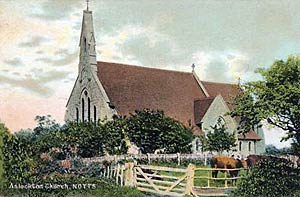

Aslockton church (built in 1891-92), c.1905.

Cramner's Mound, c.1910.

ASLOCKTON. Though this quiet village has little for us to see, it will ever be remembered for having given England a famous man who died for his faith, Thomas Cranmer. Here he was born and lived for 14 years, having lessons from the parish clerk, and exercises in manly sports with his father, whose portrait is engraved on the floorstone of his grave in Whatton church.

The old manor house of the Cranmers has disappeared; it was probably in a field where the path called Cranmer's Walk sets off to Orston. Near this path, just beyond the modern church, is a moated mound which may be part of an ancient earthwork. It is known as Cranmer's Mound, for it is said that as a boy the archbishop loved to sit here and look round the countryside as he listened to the bells of Whatton church ringing across the River Smite. Some thick walls of an ancient chapel Cranmer would know, desecrated at the Reformation, still remain in the village; they are part of a mission room.

It was in 1489 that Thomas Cranmer, first Protestant Archbishop of Canterbury, was born here. Sent to Cambridge at 14, he enthusiastically applied himself to the new learning. It was Cranmer who suggested that Henry, when deeply engaged with his efforts to divorce Catherine, should ignore Rome and have the legality of his marriage decided by English divines from the Scriptures themselves. Henry was delighted, ordered him to write a book on his idea, appointed him one of his chaplains, and sent him to Rome and Germany to expound it. While in Germany Cranmer married a second time. Returning to England, he was consecrated Archbishop, and a few weeks later declared the king's marriage invalid.

His first great act as Primate was, within a week, to publicly marry Henry to Anne Boleyn, having already been present (it is believed) at their private bigamous marriage four months before. Three years later Cranmer declared this bigamous marriage null and void, and in 1540 he presided over the convocation which annulled Henry's marriage to Anne of Cleves.

The die having been cast, Cranmer strove his utmost for the Reformation; he placed an English Bible within all men's reach: he urged Henry to dissolve the monasteries, with a view to devoting their revenues to religion and learning; and he denounced the distribution of lands and abbeys among Henry's friends.

Thrust against his will into statecraft, Cranmer was at heart a scholar-recluse, and was happiest when engaged in literary pursuits.

His melodious English lives in the Prayer Book, of which the Litany, the Articles, and most of the Collects are probably his work.

The conspiracy which induced Edward the Sixth to change the order of the succession once more betrayed Cranmer into weakness, and at the same time doomed him, for at Mary's accession he was arrested, with Latimer and Ridley. Sentence was passed, and there followed the melancholy spectacle of Cranmer's six abject recantations; and then, at the last minute, his declaration that he had abjured only to save his life, and that he died a Protestant. As the lire blazed up at Oxford (in March 1556) the courage that had so often failed him reached a height sublime, and he thrust his right hand first into the flame, because it had most offended. It has been said that his death advanced the Reformation perhaps more than that of any other sufferer for his faith.