A Citizen of the World

The Square, Beeston, c.1910.

BEESTON. The world's biggest drug factories have come to Beeston, with a floor space of over a million and a quarter square feet and weighing nearly 300,000 tons. Into its making have gone 20 acres of bottle-green glass, 37,000 tons of cement in bags which, placed in a row, would reach 320 miles (about the distance from Beeston to Paris), and 8800 tons of steel bars which would make a line 1700 miles long, from Beeston to Constantinople.

Looking out from the lovely boulevard between Lenton and Beeston is the bronze bust of the man to whose business genius this great building of glass and steel and concrete is a monument. He was Jesse Boot, Lord Trent, citizen of Nottingham and of the world, of whom the inscription says:

Our great citizen, Jesse Boot, Lord Trent.

Before him lies a monument to his industry:

behind him an everlasting monument to his benevolence.

His bust is at the entrance gates of the splendid University College which (with the whole of the Highfields estate now turned into playing fields, lovely gardens, boating lake, open-air swimming pool, and boulevard) he gave to Nottingham, his birthplace, where the dramatic story of his firm began.

The busy little manufacturing town reaches out to the meadows and fine reaches of the Trent, where a weir adds beauty to the scene. On the other bank Clifton Hall stands high in a wealth of trees, and down the valley, beyond the towers and spires of Nottingham, Colwick Woods and the Shelford hills can be seen. It is a favourite haunt of river lovers, gay in summer with houseboats and pleasure craft.

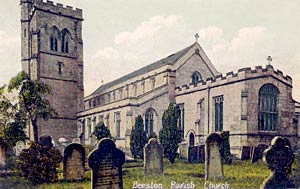

Beeston church, c.1905.

In a beautiful churchyard in the heart of the town is the spacious church with a massive tower, a stair turret climbing well above the battlements. Sir Gilbert Scott's restoration of nearly a century ago made the church almost new, except for the chancel, which, though modernised, has its 14th century sedilia and piscina, and an old image niche by the east window. The font bowl is 13th century, a pillar almsbox is 1684, and the altar table in the north aisle is Elizabethan. One of two old Bibles in a case in the porch is a first edition of the Authorised Version. In early days the church was subject to Lenton Priory, and the priory arms of an angel holding a shield with a Calvary cross are on the eastern gable of the nave.

The hamlet of Chilwell, now linked up with Beeston, has lost its big house, and we found the estate in the hands of the builder. From 1620 it was the home of the Charltons, of whom John was MP for London in 1318, Sir Richard fell on Bosworth Field, and Sir Thomas was Speaker of the Commons in 1453. The old house was spared the fate of Nottingham Castle and Beeston Silk Mill during the Reform Bill riots only because the head of the family lay dead when the mob reached Chilwell.

BESTHORPE. Near the Lincolnshire border is this quiet little place which sees the spire of Carlton-on-Trent's church rising from a green and pleasant land. It is a delightful spot when the sun shines on the Fleet and the wind sings in the rushes, for here the little river, running in an old channel of the Trent, widens out to a great sheet of water like a lake. It was here that the devastating flood of 1875 reached its height.

Where Romans Lived

BILBOROUGH. Though it belongs now to Nottingham, four miles away, it remains a peaceful village, hiding its old church in a bower of trees at the end of a lane. One of the trees is a gigantic sycamore which overhangs the gate between the churchyard and the rectory lawn.

Bilborough church in 2009.

The embattled tower of the tiny aisleless building comes from about 1450; half a century older are the square-headed windows, the porch with its canopied entrance, and a blocked doorway in the nave. The font and the east window are 15th century, and a table is 17th. In the chancel is a marble memorial to Sir Edmund Helwys, who lived at Broxtowe Hall a mile from the church in Queen Elizabeth's century. So too did Thomas Helwys, who is said to have been chiefly responsible for the formation of the first Baptist church in England. In the time of the Helwys Broxtowe Hall was the hospitable meeting-place of the Puritan clergy of the district, and before them it had been the home of the famous navigator Sir Hugh Willoughby, who perished in his attempt to find the North-East Passage through the Arctic seas.

Broxtowe Hall in the 1920s. It was demolished in 1937.

After becoming more and more a shadow of its old self while new dwellings have crept closer and closer to it, the venerable house with its stone gateway has lately been pulled down; but its proud name, taking us back to Saxon days, will not be forgotten. It was at Broxtowe that the Hundred met, and the oath of allegiance was given as each man raised his weapon.

Finds of Roman coins and pottery during building operations at Broxtowe led to the excavation in our own time of the site of a Roman settlement (or a Romanised native settlement) found near the site of the demolished hall. It was probably in existence when Claudius was conquering Britain. Among the rich store of relics found on and under the floor of a paved hut were coins, brooches, knives, bone handles, horse-shoes, spears, shears, iron nails, and fragments of pottery. Other finds on the site included bronze buckles and rings, a bronze key, glass beads, part of a pair of scales, a lead fishing weight, and a stone quern. A mile away, near Aspley lane, were found two early British coins, Roman coins and pottery, a Roman seal, and a seal with the impression of a head like that of Boadicea.

A Man Who Taught John Milton

BILSTHORPE. It lies on the border of Sherwood Forest, and the new Bilsthorpe which has grown up round the colliery has left the old village in its seclusion, with the church set high on a little hill.

There are shapely old yews and two splendid beeches among the fine trees in the churchyard. Part of the old Hall survives in the farmhouse facing the church, and it still has a cupboard in which Charles Stuart is believed to have hid during the Civil War. Traces of the moat which once surrounded the church and the hall can still be seen.

Bilsthorpe church in 2003.

The tower of the tiny church was refashioned in the 17th century. The nave is partly 14th century, and the chancel a little later. The Norman font is set on a low base which may be part of a Saxon cross. Covered with glass on a wall of the tower is a tapering stone, crudely carved with a cross, which may also be Saxon. A floorstone in the nave, with a Calvary of unusual design, is perhaps 600 years old. Three solid oak benches, perhaps older than the Reformation, were used as penance seats. The fine old pulpit has panels of linenfold.

The Saviles, who have held the manor from the 16th century, have a modern chapel with four wooden angels on the ends of its oak roof beams. A fine stone tomb, carved with arcading, has a brass inscription to Henry Savile of Rufford Abbey, who died in 1881. A marble memorial to Augustus Savile, surmounted by a little owl, has a wreath sent by Queen Victoria kept under glass; he was one of her Masters of Ceremonies.

A wall monument has a Latin inscription to William Chappell, who found peace here when there was none for him elsewhere. Born at Laxton, he became a tutor at Cambridge, where he was famous for his skill in debate. He is said to have won an argument with James the First, and among his pupils was Milton, who seems to have had a great admiration for him. In 1638 he was made Bishop of Cork, but the Irish rebellion sent him back to England, where he suffered much persecution for his faith, and was glad to find a refuge at the big old rectory by Bilsthorpe church, where his friend Gilbert Benet always had a bed for him. He died at Derby, but they brought him here to rest in the spot he had come to love more than any other. One of the altar steps is edged with alabaster from his vanished tomb.